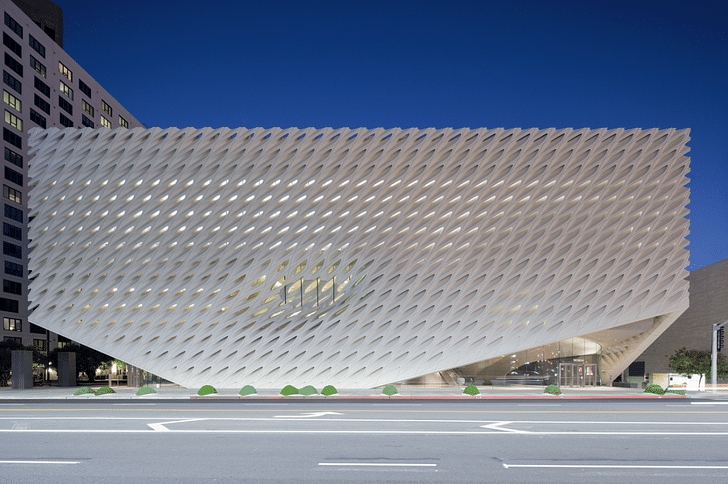

Elizabeth Diller, co-founding partner of Diller, Scofidio and Renfro, almost didn’t become an architect. In her student years at Cooper Union, Diller expressed a greater interest in pursuing film than in taking up traditional architectural practice, partly because the profession seemed like too much of a commercial pursuit. Some thirty-six years later, from the Broad Museum to Lincoln Center to The High Line, DS+R’s built work consistently pushes the visitor to experience space in an unanticipated way without providing a ready-made interpretation.

While Diller occasionally encounters limits to this sort of thinking (DS+R’s initial proposal to purposefully obscure and then gradually unveil a view of the Boston harbor in the Institute of Contemporary Art was nixed by the client), projects such as the High Line, which created an “otherworldly realm” between sidewalk and sky, have been massively successful. While Liz Diller was in Los Angeles to talk about the recently released book, The High Line, with L.A. Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne, I managed to speak with her about how her work leverages unusual approaches, her unexpected joy in consensus building, and the future direction of DS+R. An architect who once stated that she prefers to make problems rather than solve them, Diller spoke to me via phone while riding in a car. Here is a transcript of the bulk of our conversation.

I spoke to your partner Benjamin Gilmartin about the importance of writing in DS+R’s design process. Would it be fair to say that you’re always thinking in narratives?

I do like to imagine architecture as an event, as something that’s an experience. We do often talk about the first impression, how do you approach a building, what’s the first instance you feel something. We have a kind of cinematic approach to it, a kind of linear cinematic approach as far as how you enter the building. The Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston is a good example, that cinematic scenario of being right at the harbor but not seeing the view, and riding up the Beaux Arts elevator and scanning very often what you imagine is not the way people use it the view and then coming up to the 5th floor and having the view blocked off and then having it revealed. The building becomes a kind of apparatus for how you look at the view. In that project we pretty much scripted all those experiences. As I mentioned when I was with Christopher [Hawthorne], that very often what you imagine is not the way people use it. It’s very useful to get the thinking through that way, it’s the way we design. It doesn’t really matter if it’s seen that way or it’s appreciated another way. Sometimes people add a lot of reading into what we do, and that’s okay too. Like the Blur Building is a perfect example. It’s a building out of mist. Some people interpret it as a religious symbol, some people interpret it as surrealism. Some people thought it was a political condition in Switzerland, leanings of being in and out of the U.N. So I just love the idea that people are making meanings out of it. You just can’t exactly control it. You have to take positions on what you ration. The rest just happens.

I’m glad to hear you say that. Contemporary architecture often seems to lack a strong narrative. I’m glad you definitely have an idea of what you want to convey but you’re also okay with people putting their own meanings on it. I think that makes it art.

I think so – there’s nothing worse than meglomaniacism [sic] when it comes to architecture. A big statement, everybody has to get it. I think people get it, like an onion, that there are different layers of meaning. People understand different things. That project – the Blur Building – it was incredible. We had art historians there that thought about it as a history of painting. That was a very academic reading of the work. But then there’s all the other readings. The kids that cry when they’re inside, that get scared. I feel charged by seeing the whole array. As long as we connect emotionally or intellectually to the public, that’s what we care about. Connecting.

In terms of the future of the studio: what’s your idea—do you have any directions or problems you’d like to make? What would you like to see happen with DS+R?

I’d like to increase the agency of the architect more and more. I’d love to be our own client. I’d love to put new ideas on the table and build support for new ideas around the institution, let’s say. And be able to realize projects like that. I use The Shed Culture Center as an example because it’s an idea that was borne from nothing. It was just a seed. We thought this was an important thing, it could be really really great. I'd like to increase the agency of the architect more and more The idea of even putting something out there: that was sheer naïveté! But it worked because it was naive and we weren’t stopped by cynicism, and the idea of not getting anything done, which I think a lot of architects feel. They just can’t get things done. They’re slaves in a kind of service industry. And that’s not what I’m interested in. I’m interested in rethinking conventions. Conventions that work are fine, but a lot of conventions don’t work. And they need to be re-invented, institutions need to be rethought. I’d like to be in a position where I’m part of a client team of not just realizing the dreams of a client, but realizing some of my own dreams. And doing all that it takes. And they’re usually urban and institutional and they involve social and broader cultural issues. That’s the way I’d like to connect with contemporary culture.

You’ve spoken about consensus building as something you initially didn’t want to do, and now it seems like you’re relishing it: how to orchestrate vast groups of people to create your kind of vision, right?

I like things that are hard to do. I actually gravitate towards impossible projects. It’s not just for the sport, it’s usually because there’s a lot of work to be done, and people get defeated by bureaucracy and all sorts of economic issues and issues of convention and comfort with the status quo. And so forth. I have a lot of energy, and actually I’m satisfying my own intellectual curiosity just to keep the studio research based, research and application. It’s comfortable working on paper. It really wants to come into public space. It’s rethinking the norm. I’m just very optimistic about the possibilities for architecture.

That’s wonderful to hear!

I tell my students, “Don’t give up!” You’re examples of how it could work. Basically, when I left school, I had no intention of being an architect. You could never get anything done. Film was pretty interesting, you could contribute in a serious way. Anyway. Architecture changed my life. So I like to do lots of things at the same time. Lots of different media. Architecture is really, really important. It affects everybody else’s lives in a permanent way. Coming from film, wanting to do films, it was a pretty big step for me.

It seems like architecture has entered popular consciousness more in the last fifteen or twenty years than it had in the last one hundred. Because you have this background where you’re coming from film, which still is a popular medium, you’re integrating two professions or mediums which didn’t seem to have that much in common, or at least more consciously than they might have. I’m sorry, this isn’t really a question.

It’s an observation, it’s a good one.

It’s a delight to speak with you.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

11 Comments

Is that the Blur Building or the Folk Art Museum Demo....

"They’re slaves in a kind of service industry. And that’s not what I’m interested in."

Can't say most of us are interested in being slaves. I think most people would like to have been privileged to design the broad or Lincoln center.

Free tuition at cooper Union was one step that helped you escape slavery.

Luck also played a big role. Starting out as an artist and a professor at an Ivy League school.

I suppose I'd have the same luxury to get things done if I were in the same place.

Nice architecture though.

Luck and connections are 90% of architecture.

...the other 10% is the real joy

"They’re slaves in a kind of service industry. And that’s not what I’m interested in."

I assume she's talking about the team of extremely talented folks that are figuring out the structural connections, waterproofing details, and managing the people to make her vision a reality.

Anyhow, nice buildings and interesting read. Would love to work on a project where I get to think about the cinematic experience.

^ I imagine it was an interesting company meeting.

Hope she baked some cookies.

cynics

but that was funny Nate.

The Folk Art Museum was Tod Williams and Billie Tsien.

The hero worship of these architects is sadly a media driven phenomena and all the more attraction to those who would create narratives rather than structures such as a film maker. They all attend the same schools, then lecture on the same circuit, commission from the university / public sector / government funnel...and it all leads to an incestuous network of barnacles clinging to the waning idea of architecture as spectacle, that a grand building will save us or change us and keep us on edge until the sequel is released. I was recently at the Broad, and a more anti human, anti urban, jagged anxiety inducing hulk I've never encountered, although I haven't been to Denver yet. There is real architecture being made all over, with lasting importance beyond sound bites and magazine articles, architecture that continues the forward momentum and not playing 20th century Hollywood architect as hero roles. Step out from the echo chamber people, architecture as a consumable media, like film is a horrifying idea - the suspension of disbelief, the separation and escapism is fundamental to film but architecture is about reality and needs firmer set of ideals than the next big hit.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.