The role that architecture plays in our individual and communal lives is often overlooked, yet in an age when environmental crises are imminent and individuals increasingly turn inward to their electronic devices, an investment in quality spaces that promote social and ecological well-being seems more urgent than ever. This conundrum begs the question: how can a deeper appreciation for architecture be instilled in twenty-first century society?

This question may be best addressed by museums, which are uniquely suited to present the complex histories of architecture and the built environment. Architectural knowledge has traditionally been difficult to disseminate, due in large part to the challenges inherent in representing multi-sensorial and site-specific space. If a person has not visited a particular building or site, they must rely on its representation through other media, such as drawings, models, and photographs. Through exhibitions and programs, the museum can bring such representations together in a single space to reveal the patterns and variances across styles and their global and local interpretations, to compare the “good” architecture to the “bad,” and to trace the transformation of spaces as they have been conceived, constructed, and used. The museum serves as a primary venue for promoting architectural knowledge and appreciation—not typically addressed in K-12 education—among the public.

A debate over how museums should integrate architecture into their activities recently surfaced following the announcement in April 2016 that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) would temporarily close its dedicated architecture and design galleries due to the institution’s ongoing building renovations. This announcement raised an outcry from the design community. Several architecture and design writers—like William Menking at The Architect's Newspaper and Marty Wood with Metropolis, not to mention numerous online commenters—expressed their concerns over the closure and Indeed, some of the most exciting and promising opportunities for twenty-first century museums exist entirely independently of their physical space.considered its potential effects for the field. On one hand, MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design would have to compete with other curatorial departments for exhibition space in the Museum’s general galleries, possibly resulting in a compromised representation of architecture and design materials in public displays. On the other hand, the materials’ inclusion within more broadly conceived multi-disciplinary exhibitions could provide them with both a richer context and a wider audience.

MoMA’s Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, Martino Stierli, addressed these concerns in a public response and in a recent interview. He has assured readers that the department will still be represented in both medium-specific and multi-disciplinary shows, noting several architecturally-focused exhibitions and programs scheduled for the coming years. He also notes that plans for the building renovation are ongoing, and that the years leading up to its completion will mark a period of experimentation “with new ways in which to bring the vast and diverse holdings of the Museum’s collection into new and meaningful encounters and dialogues.” While Stierli’s remarks have addressed the concerns at hand, the indication of an ongoing, experimental planning phase should be seen as an opportunity to engage in further dialog about how we interpret and share architectural knowledge today—a question that extends beyond mere nostalgia for or defense of gallery real estate.

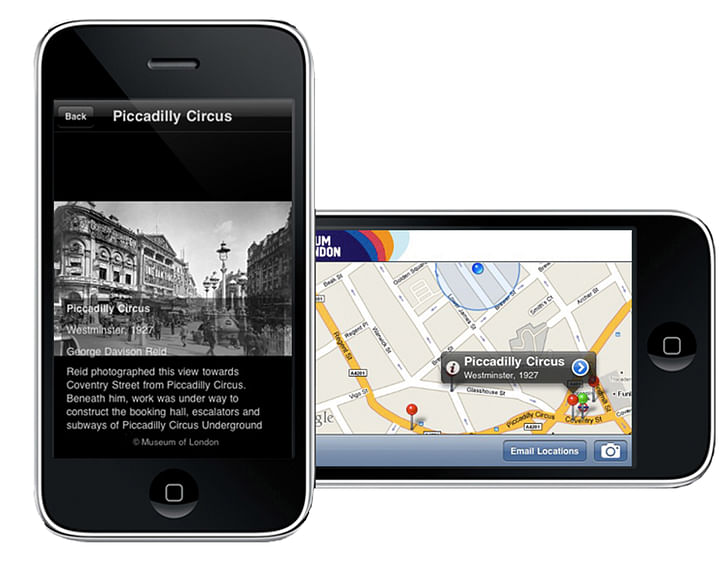

Indeed, some of the most exciting and promising opportunities for twenty-first century museums exist entirely independently of their physical space. Within the field, architectural historian Dianne Harris has called for a shift in how the history of the built environment is conveyed, pointing to the employment of digital technologies as a key strategy. The digital age provides new possibilities for engaging the public with cultural materials. Instead of fixating on representation in terms of square footage, we should focus on developing ways of achieving higher quality public engagement.Institutions can collaborate to bring discrete collections together to build rich and dynamic online exhibitions, introducing new and more nuanced perspectives to the previously established canon. Examples of such projects include Form and Landscape, a series of digital exhibitions about the history of Los Angeles produced by the Getty in collaboration with the Huntington Library; The University of Glasgow’s Mackintosh Architecture, an online catalog of the work of architect of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, which documents drawings, photographs, and people associated with each project through archival sources; and the Museum of London’s Streetmuseum app, which allows users to retrieve historic photographs and information about their city as they move through its public spaces. The use of digital technologies to make architectural history more relevant and accessible to a broader audience can in turn nurture a more widespread appreciation for and investment in our built environment.

While it is true that MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design may have to compete for its representation in limited gallery space during the three-year renovation period, this is nothing new in the museum world. Museums face an ongoing challenge to achieve a balanced yet dynamic representation of their collection materials across their activities while also working within the constraints of available space, time, and funds. Instead of fixating on representation in terms of square footage, we should focus on developing ways of achieving higher quality public engagement. With leading institutions like MoMA exploring new ways of broadening their curatorial activities, and with today’s available technologies, it is the perfect time to reconsider the enduring importance of architecture and how it can be represented in the museum’s traditional spaces as well as beyond its walls—both in the digital realm and in society.

Bridget is a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture, where she is enrolled in the M.S. in Architectural Studies (Interdisciplinary) program. Through coursework in architectural history and information studies, her research focuses on how the history of the ...

1 Comment

This assumes that MoMA is still serious about architecture issues, when they clearly have abandoned them. Just look at how Barry Bergdoll and Pedro Gadanho fled the sinking ship last year... It's not an accident. Its a shame since there are many ways MoMA could address architecture without space, but they just don't have the intellectual muscle to do it. So they show Pac Man instead ... So revolutionary! 80s video game nostalgia! And throw in a few weak social architecture disaster porn shows to please the narrative journalists at the NYTimes and make the Upper East Side wives feel good about themselves.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.