Working far beyond the simplistic notion of crowdsourced design, WikiHouse Foundation is a building system and a stamp of approval for open-source innovations around the building industry.

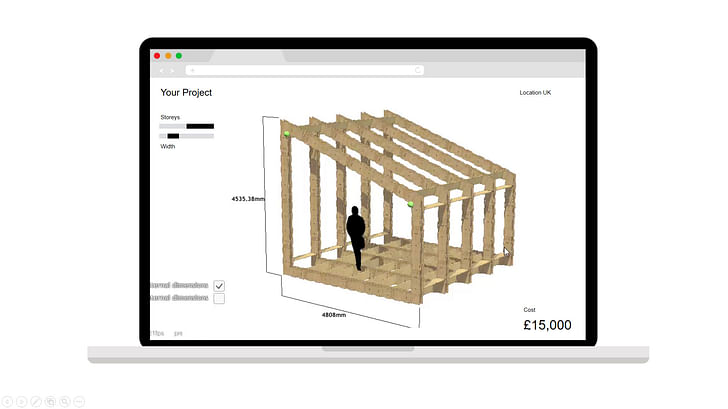

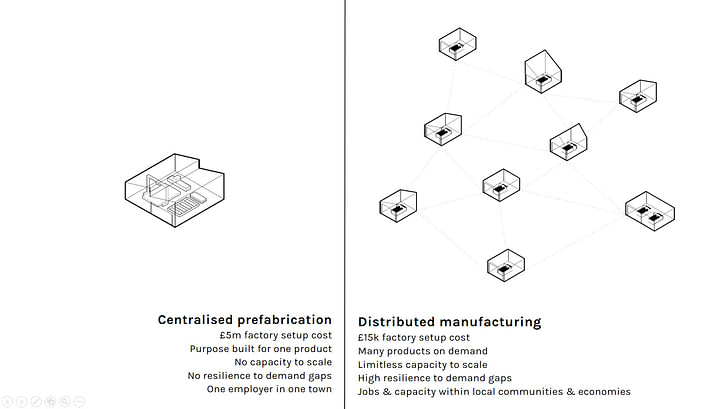

The WikiHouse ethos is based around the concept of a digitally fabricated and manufactured building system that can be self-assembled. Their aim is to lead the way in open-source innovation for the architecture and construction industries globally. At present, the non-profit hypothesizes two potential future options for would-be manufacturing partners: a centralised prefabrication plant for £5m factory set-up cost, and a smaller distributed manufacturing site for a £15k factory set-up cost. The manufacturing process could then facilitate the construction of materials of four WikiHouse buildings, with the following estimated costs: a studio for £12,500, a micro-house for £45,000, a longhouse for £90,000 and a townhouse for £130,000.

Based in London, but with an international presence that you’d expect from an organisation borne from the open-source community, I spoke to Alex Whitcroft, WikiHouse’s Architecture Lead, about the Foundation’s basic premise and vision for the future.

What is WikiHouse doing right now?

We are currently in the process of building a platform on top of the hardware, to give consumers access to be able to deliver the building process themselves and take control of architecture, in a way that’s like buying a piece of IKEA furniture rather than trying to deliver a once-in-a-lifetime project.

If WikiHouse is pitched into the planning process, won’t the results adhere to a certain architectural protocol?

The current WikiHouse chassis is a high-tech timber frame and you can clad it in whatever you want, and I think that’s very important. We can have something that is very high-end, something that is a bespoke piece of design, very exclusive and something that feels absolutely run-of-the-mill and you wouldn't know that they were built in the same way.We want good quality design, but we don’t feel, as an entity, that we should be prescribing what things look like.

It’s fascinating to me as an architect, most people think that what you do is design in terms of visuals and beauty. Architects on big projects become window dressers: cladding architects. So to take the completely different end of the spectrum and say “We’re going to work from the economics up, and we’re going to stop before we actually reach what it looks like—because that’s for someone else, that’s for an individual architect, provider, or design engineer working on a project to decide,” is an interesting stance. We’re building systems and building procurement design; it’s a very interesting and exciting realm to be in as an architect because it's refreshing, different and a lot more profoundly important.

As lead architect, what of aesthetics in the type of work that WikiHouse is drawn into?

There could be a new aesthetic borne from new technologies, there often is. At the same time it's not on our agenda to change what architecture looks like. In the grand scheme of socio-economic improvement, it's not important. We want good quality design, but we don’t feel, as an entity, that we should be prescribing what things look like.

How does the concept of community in open-source sit with trying to unite practice under an umbrella like WikiHouse?

The concept of the brand is important in [the] open-source debate, finding a balance between brand and something we’ve all built together is what the umbrella brand of WikiHouse is all about. We’ve been able to highlight and flag up particular people that are really pushing us like Spacecraft Systems Ltd in New Zealand, ARUP, Architecture 00, KIN Architects, Projects By IF—businesses that are around this process; these guys are doing great work.

Can you explain the concept of open-source in relation to WikiHouse?

Open-source works in layers. WikiHouse is Creative Commons: this is for the hardware side of things. If you want to take the existing system and innovate on it or develop a completely new product or system, you can just go into the online system of repository files and you can create a folder for yourself and start editing and view other people’s files. We’re not just 12 architects in a room postulating about what the future of architecture will be, we have people who say 'that makes no sense, that's just the way your industry does that'People can view your edits and once you put it in there, part of the terms and conditions is that you are releasing it as an open license, so that it can never be black-boxed by someone and taken and run away with. The Commons are completely un-curated; there could be a fantastic gem in there that will completely change the world, or there could be someone fiddling around working out if they can make a small test box that they are never even going to fabricate, to someone doing a high school project.

The second layer, next step up, is that we have a process of curation where a central body, the Foundation element of WikiHouse, is the criteria of quality assurance that we are comfortable with. These then become catalogued, more accessible and front-line. As we move from commons to the catalogue, we can put a stamp as “passed by industry” on certified products.

The third layer of the open-source is the idea of certified providers and service providers. This is a collection of curated solutions and innovations and these are people that we know that will effectively deploy them, if you want to not do it yourself.

With this third layer, are you aiming towards a futuristic vision of something like RIBA?

There are some interesting overlaps with professional bodies like RIBA with the third layer of open-source, and the idea of certified providers and service providers. We've got people that actually know our technologies from start to finish, which in some way is actually a more powerful way of certifying individuals. In the same way, we’ve got quality assurance requirements around innovations and solutions, and we can also have them around professionals. If you work with a WikiHouse system it will be sustainable, energy efficient, etc. but the only way we can guarantee that is to say if you work with a WikiHouse certified professional. That’s the overlap with RIBA.

What qualifies WikiHouse as a new standard for open-source innovation?

We are a pretty diverse group. We’ve got people who are digital service designers (graphics web platform technology); we’ve got software developers who have no background in the built environment whatsoever, or even design, it’s just about tech; we have people who are architects, like myself, who’ve never built a software platform but find the idea fascinating. And that, as a starting point, is quite a good one. We’re not just 12 architects in a room postulating about what the future of architecture will be, we have people who say “that makes no sense, that's just the way your industry does that, the way the software industry would do it is more efficient—so let's do that instead.” So having that diversity of opinion, not just on the team, but globally, is great.

How far does WikiHouse extend as a concept to embrace and co-work with other dependent industries?

We are very keen on collaboration and spreading where WikiHouse can help and where we can provide tools, whether that’s protocol, software or hardware to help the process. On the other hand, we don’t have an acquisition model, so we don’t look at land as a possibility and say, “Maybe we should become developers.” What we want to do is find developers or architects, and say, “actually we could start just using this model, it would allow us to in the same way that Airbnb reduces booking costs for a hotel room, WikiHouse and open-source aims to do the same kind of thing for building industry projects.expand our horizons on that,” or a housing association. We’ve had a number of conversations with housing associations, including South Yorkshire, saying “we’ve got a bunch of these marginal sites, we’d like to try your model.” Therefore, it's a sort of partnership approach as opposed to a traditional one. In theory, we could take a more acquisition mix, an empiric kind of approach, but then suddenly you become someone that no one wants to collaborate with.

Has there been any backlash to WikiHouse?

Of course. One of the common questions we have is often from architects more than engineers or anyone else, saying, “Doesn’t this put architects out of a job?”

The answer is “No!” My background is as an architect and I still practice. I'm not frightened of what an open-source construction industry brings. As architects, we spend a lot of time dealing with transactional costs on projects—in the same way that Airbnb reduces booking costs for a hotel room, WikiHouse and open-source aims to do the same kind of thing for building industry projects. We spend a huge amount of time writing emails, answering questions, working out where responsibility lies. What WikiHouse helps to do is reduce all those transactional costs.

What’s the business model for WikiHouse?

WikiHouse is a registered commercial non-profit organisation, so we are locked and secure and that position isn’t going to change. We don’t give money to shareholders but we do have revenue, we do have people coming and saying, “Can we buy you for millions?” And we reply, “We’d love your money but you can’t have any equity, you can have a seat at the table.” If it’s a person with a great vision that will guide and advise they would have great sway and influence.

What do these wannabe buyers of the company think that they’re getting?

We’re still considered a start-up. The classic VC model is the potential of an exit so either the company itself gets very big and very wealthy and then their shares are worth a lot, or they are waiting (which is far more likely in the start-up world these days) for the company to sell to someone big like Google or Amazon, and those are crazy prices. I do still find myself calling us a start-up but it’s a very loaded term because of the adopting model of move quickly, go bust, or sell, VC capital, etc. So I would say we are a small, agile non-profit at the moment and we are expanding and driving forwards pretty well for a commercial non-profit.

What do you need in order to realise the full potential of WikiHouse?

At the moment, consortium funding is one of the big challenges. I think in five years’ time, this model will have become more established, and it will have become a much easier conversation with people, and the industry will have moved a lot further forwards. The idea of people contributing to building communal infrastructure for their industry is not something that the construction industry gets instantly, so I think we are at the bleeding edge of that innovation.

If we can make the construction industry more forward thinking and more open to this kind of approach, then that would grease the wheels enormously for us and the people like us.

How can WikiHouse help shake up the architectural landscape in the UK?

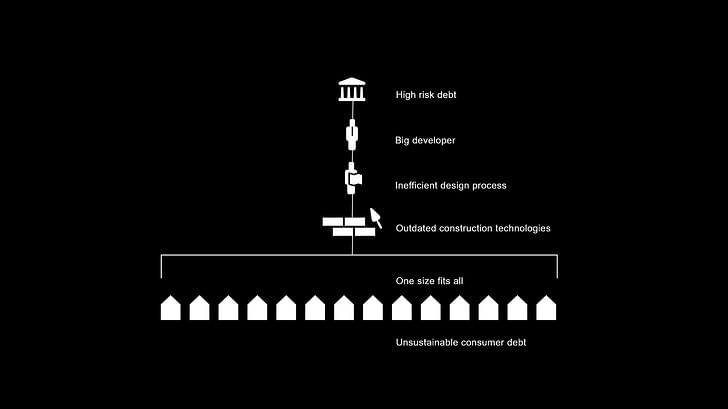

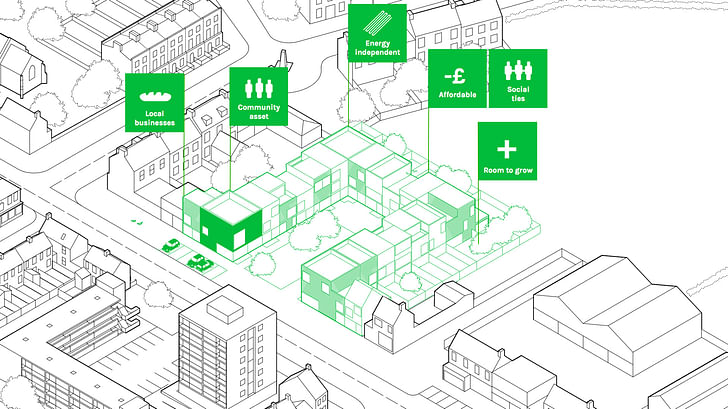

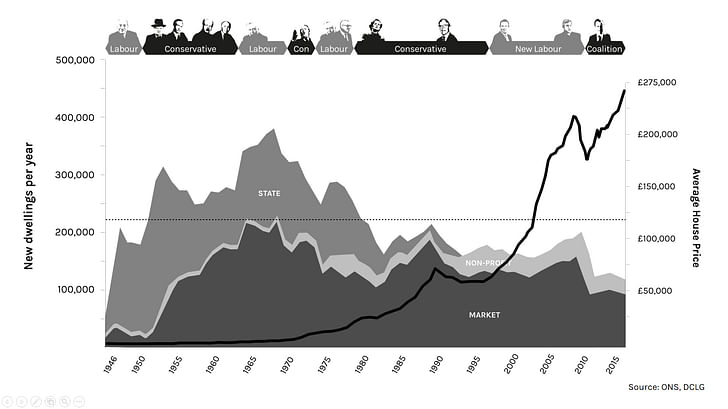

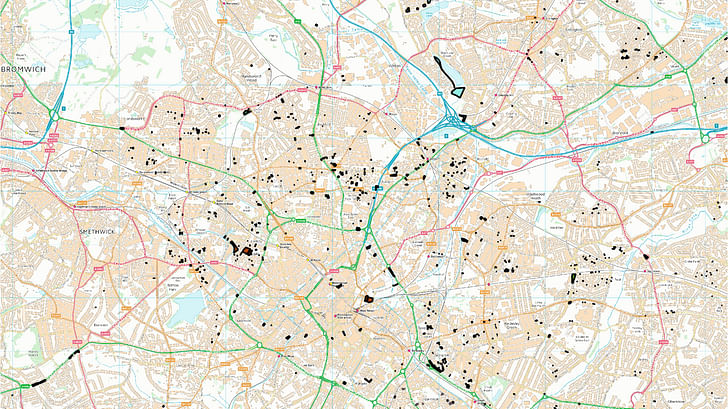

WikiHouse can bring down the level of cost of social housing usually built at scale, as a one-off house. We can build a building for less than a £1,000 per square metre using self-build, which usually means you have to build a whole bunch of houses all at once just to get the economies of scale to get the cost down, so that makes small sites suddenly viable. In Birmingham, there are about 14 hectares involved in a study done by a team based out of Impact Hub Birmingham, called DemoDev. That's nearly 3,000 family houses worth of land that, at the moment, is just sitting there.

There is an alternative to the big developers and once we start to get a more diverse land market, we won’t see so much land banking. Smaller house builders, SME’s or custom builds just want to buy and build, so if we start to unlock smaller sites and start to reduce that imbalance of economies of scale we’ll start to see a more agile market. We’ll start to see more sites developed and we’ll also see a reduction in land prices potentially, and more accessibility to land, because you are not buying land on the basis of what a developer thinks they can make a profit on in 10 years time when they eventually decide to build. It’s about it happening right now.

This feature falls under Archinect's July theme, Domesticity. For more domesticity-related features, head over here.

Corrections 8/3/2016: the figures quoted for WikiHouse factories are potential estimates, not current prices as previously stated. The cost for the WikiHouse buildings listed are also estimates, and not retail prices. The study in Birmingham was conducted by DemoDev, not WikiHouse.

Robert studied fine art and then worked in children's television as a sound designer before running an art gallery and having a lot of fun. After deciding that writing was the overruling influence he worked as a copywriter in viral advertising and worked behind the scenes for branding and design ...

1 Comment

You are late. I am currently building a post and beam simple box using my own jig built 4x8 panels. I hope it is simple enough to attract homeless vets to accept a challenge to build their own "house!"

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.