For most of us, ‘home’ conjures a sense of safety and security. But a home is a fragile thing: vulnerable to quaking ground, rushing water, violent winds—not to mention, the volatility of finances and health. This has never been more true than in the time of climate change. The global thermostat of the home in which we build our homes is on the fritz.

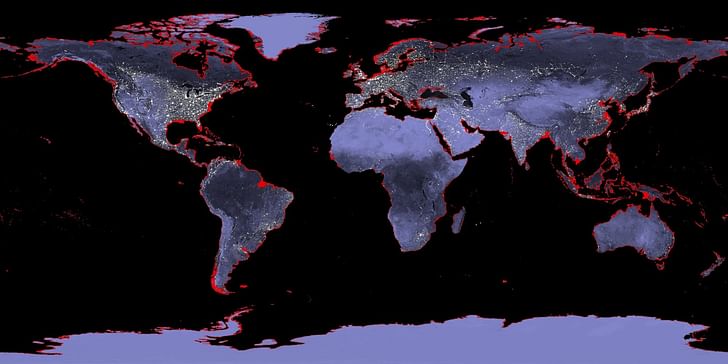

As global temperatures rise, the polar ice caps have begun to melt, bringing up sea levels around the world. Simultaneously, a veritable witch’s brew of meteoric, atmospheric, and oceanic forces are creating more intense and frequent storms. If you live in just about any coastal region, your home is likely at risk from crashing waves and rushing floods.

Households will be particularly affected by climate change“Households will be particularly affected by climate change, which will include uncomfortable summer heat waves and more frequent and severe floods and periods of drought,” write ARUP in a report entitled “Your Home in a Changing Climate,” which focused on threats in the United Kingdom. But a report isn’t necessary to convey this point when the images of the devastation Hurricane Katrina unleashed on New Orleans (and the rest of Louisiana, as well as Mississippi, Florida, Cuba, and the Bahamas) remain burned in our retinas. Or Hurricane Sandy. Or recent floods in England or the Netherlands, in Pakistan or India or China or Myanmar.

According to a recent paper in National Geographic, “As many as 13.1 million people in the United States will be in the path of flooding by 2100.” That’s three times the current population currently at risk. As more and more people flock to cities, the fallout from major sea-level related disasters will increase. So what can be done about it? Well, that depends—on where you live, your finances, and how quickly sea levels rise.As many as 13.1 million people in the United States will be in the path of flooding by 2100

Take the task of protecting a home in New Orleans, for example. As Hurricane Katrina made abundantly clear, the city’s not-so-old defenses weren’t as strong as many assumed—particularly in economically-depressed areas. Byron Moulton of the New Orleans-based practice Bild Design explained that, if you look at an 1880 map of the city, its borders pretty much correlate with the borders of the regions of the city that were spared the brutality of the storm. Before the levee system was in place, all buildings rested on high ground. “In short time, people forgot about the risk,” Moulton explains. Now, large populations reside on ground that’s below sea level. And, while post-Katrina defenses have been added to the levee system, such as water pumping systems and new legal regulations, “we’re still at a little risk,” says Moulton. So how do you protect New Orleans homes against inevitable flooding?

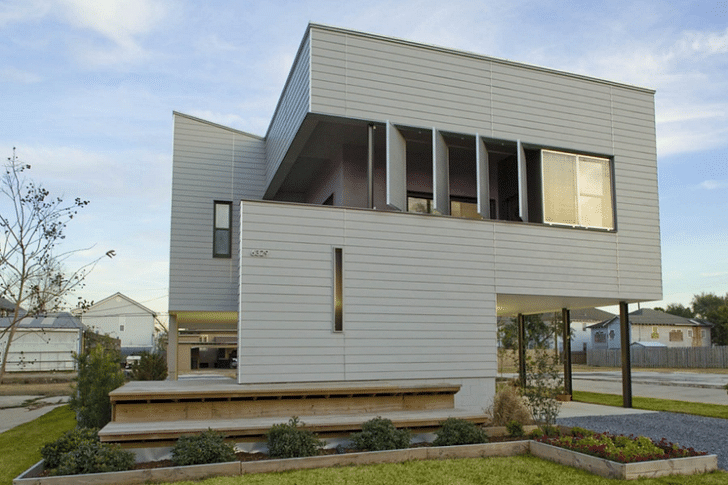

“There’s lots of ways to do it, frankly,” Moulton told me. If you’re trying to preserve an existing structure, which are common in the historic city, then your best move is to underpin the building—essentially, jacking it up in the air, putting in steel beams and a new foundation. With new construction, pyles are the predominant strategy, but since a house on stilts can look a bit funny, different techniques are taken. New Orleans has soft clay soil, so pylons are driven down to where the ground is harder, a concrete cap is poured, and then a better-looking foundation laid on top. There are other measures possible, but this is one of the most popular. “The city requires it,” Moulton explained of a minimum floor height for new residential construction. “And FEMA funding is available for homeowners to lift their houses out of the floodplain.”You can’t turn your back on the neighborhood

But if you’ve ever been to New Orleans, you’ve probably noticed its street life. Towering houses aren’t exactly conducive to front-porch culture. “You can’t turn your back on the neighborhood,” Moulton states. So Bild has employed other strategies, such as lifting one unit of a two-unit home while keeping the other on the ground, heavily anchored. If flooding occurs, the residents can take refuge in the elevated unit, while the other unit takes on water—intentionally.

This represents a combination of two of seven strategies outlined by Laura Tam of the San Francisco Bay Area-based group SPUR in an article entitled “Strategies for Managing Sea Level Rise”: floodable development and elevated development. Unfortunately, such strategies aren’t necessarily adaptable to San Francisco and its environs. “Some types of housing are never going to be able to withstand flooding,” Tam told me over the phone. And elevated development isn’t appropriate in earthquake-riddled California.What the right strategy is for any one place depends on so much

“A lot depends on a situational assessment,” Tam explains. Each particular area is different and what may work in one place may not work in another, even in the same city. “What the right strategy is for any one place depends on so much,” she elaborates. “What land use is like; what development looks like, now and in the future; what land values look like; whether uses are residential or commercial in nature; whether there's a lot of elevation and topography or not; whether or not the shoreline can effectively host a large wall, which isn't a viable thing to do in some places.”

And, in general, any conversation about mitigating the risks of sea-level rise for a private home necessarily involve planning and design at the regional level. “I think in a lot of places and, in particular, places that are settled densely, you have to look at more of a neighborhood or a district scale strategy. You can't take a building-by-building assessment and flood-proofing approach.”You can't take a building-by-building assessment and flood-proofing approach

One such regional plan is “Living with the Bay,” developed by Brooklyn-based Interboro Partners for their winning Rebuild By Design submission. “The damage from Sandy was caused primarily by storm surge. But unfortunately storm surge is not Long Island’s only water-related threat,” they write. “Long Island faces serious threats from sea level rise, stormwater, and wastewater. The latter two threats are a major source of pollution: unfiltered stormwater runoff entering the bay by way of the region’s rivers and creeks threatens the bay’s ecology.”

Their comprehensive resiliency plan for Long Island, where 35,725 residents were displaced by Hurricane Sandy, takes a multi-pronged approach towards these multi-faceted, and co-constitutive, risks. The plan includes five strategies: “a protective infrastructure that doubles as a landscape amenity” for the very vulnerable barrier islands; new marshlands that help prevent erosion and can absorb water surges; “slow streams” to mitigate run-off; a green corridor built in part to encourage relocation further upland; and recovering and strengthening sediment displaced by Sandy.

But even such a comprehensive plan runs into other issues, such as legal and policy impediments. “Coordinated, regional decision-making is essential to the resiliency-building process. This is easy enough to say, but it is of course harder to achieve,” Interboro added over email.Coordinated, regional decision-making is essential to the resiliency-building process.

“Because New York is a ‘home rule’ state, municipalities have the power to effectively chart their own course, which creates a barrier to the kind of regional decision-making that is required to adequately address regional issues like housing, transportation, or sustainability.

“Home rule can lead to redundancy (the State of New Jersey has 585 school districts), but it can also distract us from the simple truth that our fates are shared—that decisions made by and for one municipality have consequences for other municipalities in the same region. Disasters don't stop at municipal lines; why should our responses?”

To help facilitate regional cooperation, Interboro has developed a strategy they call “grassroots regionalism”. In part, this involves figuring out ways that regional responses can also improve daily life on a local level, such as new recreation areas and more greenery. Interboro actively solicits community input in their design processes. Their “grassroots regionalism” also involves appropriating existing forms of regionalism, which they note are already happening all around us, such as sending-receiving relationships among schools or watershed management areas.

If we’re going to build protective structures, there is simply no reason not to add value to them so that they do more than merely protect.While disasters produced by the (larger) disaster of global warming and sea level rise threaten the solidity we associate with being at home, mitigating and preparing for them doesn’t have to diminish the quality of everyday life. In fact, disaster preparedness can improve neighborhoods and help foster a sense of community.

“Architecture that protects us from the occasional disaster (for example, a terrorist attack or a flood) too often requires us to sacrifice things we enjoy about everyday, non-disaster moments,” states Interboro. “It's important that each and every investment in flood protection in one way or another improves everyday life. If we’re going to build protective structures, there is simply no reason not to add value to them so that they do more than merely protect.”

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.