The first issue of Pamphlet Architecture, the high-minded zine-like experimental publication started in 1978 by architect Steven Holl and bookseller William Stout, wasn’t exactly readable. “Its cover was printed by Mark Mack on letterpress in black ink on black paper,” Holl recounted over email, describing the publication’s beginning. Pamphlet 1: Bridges “drew scorn from the head of Rizzoli Publications in New York who told us, ‘It’s impossible to see; we can’t carry it.’”

Apparently people could see it enough, and did read it. Pamphlet began as a collaboration between Holl (in New York City) and Stout (in San Francisco), in a way similar to many independent publications, especially in the liberated punk zine culture of the 1970s: “spontaneously and obscurely… an enthusiastic utterance without a defined audience,” in Holl’s words. Each issue held the work of one architect, but didn’t necessarily define a focus or editorial form for its writer – so long as imagery and text fit onto the 7” x 8.5” paper, the works fit no one category other than experimental. Distribution was limited to a handful of bookstores in New York and Stout’s in San Francisco, where volunteer “Pamphleteers” delivered the issues. Early titles include “Stairwells” (Livio Dimitriu, 1979, #4), “Alphabetical City” (Steven Holl, 1980, #5), and “Einstein Tomb” (Lebbeus Woods, 1980, #6).

Pamphlet has published issues focusing on the work of to-be well-known architecture names, celebrated for the inspiration inherent in their “paper” (fittingly) architecture – Zaha Hadid (#8, 1981), Lebbeus Woods (#6, 1980, and #15, 1993), and of course, Holl (many issues). Altogether, its 35 issues, released somewhat regularly for nearly the last 40 years, hold a particular sway in the world of architectural discourse – but that wasn’t destined from the start.

“It was impossible for [Holl] and his buddies to get published”“It was impossible for [Holl] and his buddies to get published,” Kevin Lippert, founder of Princeton Architectural Press (PAP), told me over Skype, describing the atmosphere of architectural discourse in the late 1970s. “I think the only magazine at that point was Progressive Architecture,” Lippert recalled, which he described (with the slightest amount of derision) as “mostly interested in postmodernism.”

Pamphlet was very theoretical, and Lippert, an architecture student when he first came across the publication, loved it, recognizing its value among his peers as “affordable and incredibly interesting”. By 1985, Lippert convinced Holl to let PAP run the production and distribution side of things for the publication, allowing it to stand on firmer financial ground than the "optimism of the indefinite" that defined Pamphlet's early years. It was made into a non-profit in 1990, and under Lippert’s guidance, submissions are now selected through an open competition model. Holl still presides over the jurying.

Pamphlet is not a flashy tome for your coffee table, and as such, doesn’t rake in the publishing big bucks, but it doesn't need toWith PAP keeping Pamphlet's ducks in a row, the publication began receiving some support from grants, including from the National Endowment for the Arts – that money is used mostly for awarding the winner, and turning their architectural proposal into something that could actually be published. Pamphlet is not a flashy tome for your coffee table, and as such, doesn’t rake in the publishing big bucks, but it doesn't need to: “It’s not a moneymaker but it’s not a money loser either,” Lippert explained. “It’s the quick and dirty, ideas-driven things that we can’t do big fancy books about.”

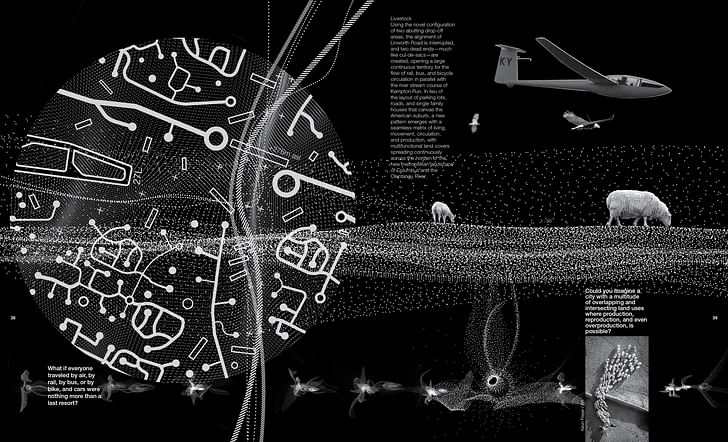

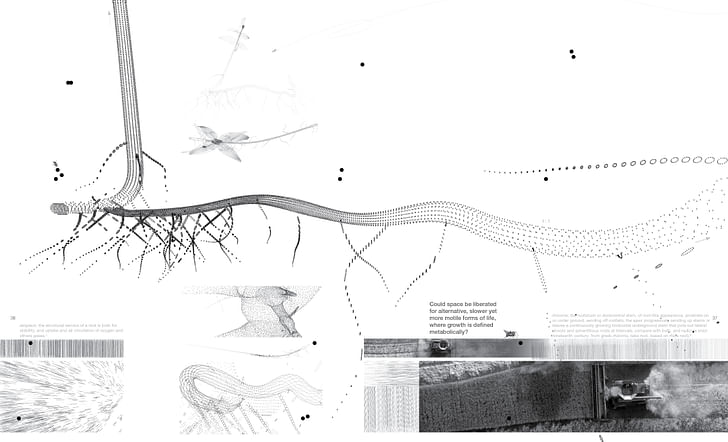

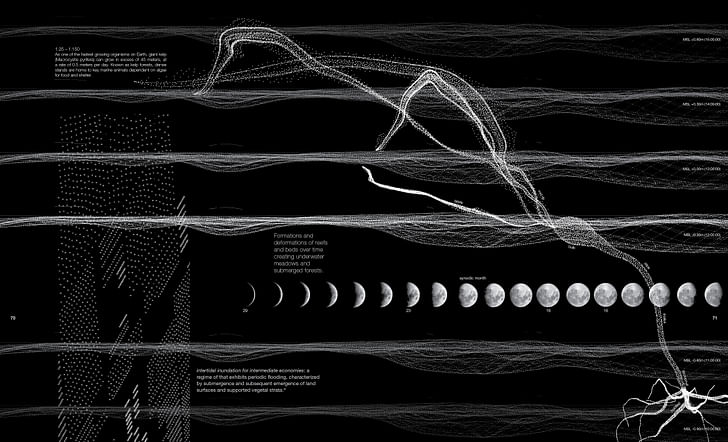

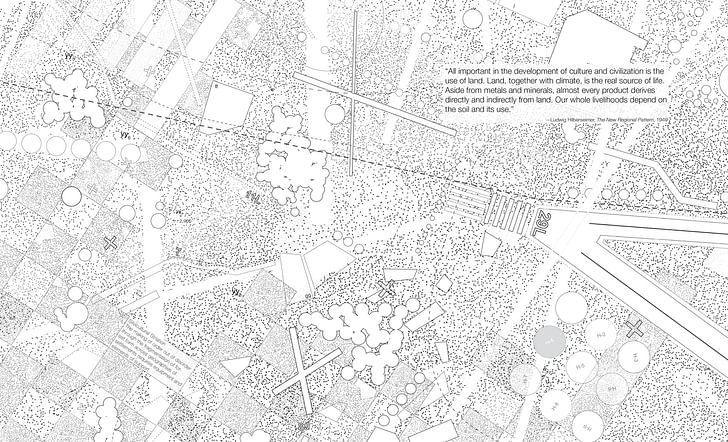

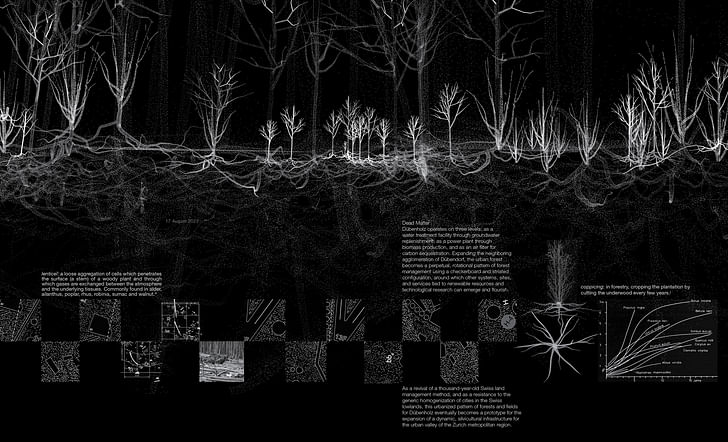

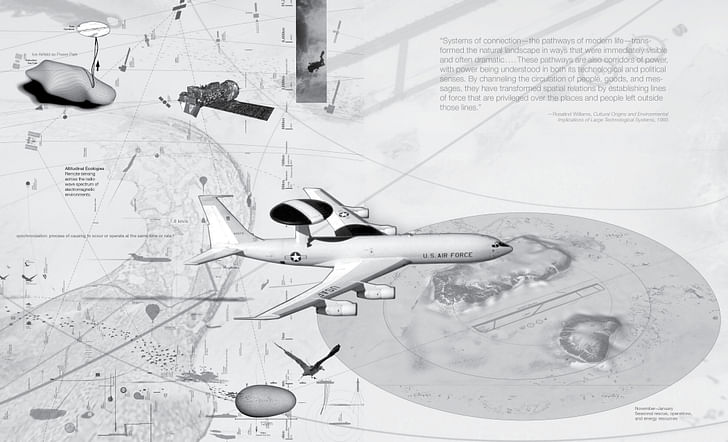

Pamphlet recently released its 35th issue, “Going Live. From States to Systems,” which is not only printed in visibly contrasting shades, but comes alongside the launch of pa35.net – the first time the issue and its featured project have been launched alongside one another. The winning submission is by Pierre Bélanger, an Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at Harvard’s GSD, and project curator of Canada's pavilion for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. “Going Live” also features correspondences with Keller Easterling (Yale University) and Sanford Kwinter (Pratt Institute), and an afterword by James Corner (Field Operations). Bélanger’s project is interested in, as the title suggests, the construction of human understanding through intermingling systems, rather than a static set of hierarchical entities – a switch in mindset provoked by the emergence of ecological research and understanding in the 1970s and 1990s. It's a fitting issue for a bit of extra attention, reflecting back on the mindset emerging in the era Pamphlet was founded in.

In Holl’s mind, Pamphlet may continue so long as PAP decides to keep it going, and Lippert is happy to carry the mantle. The issues may no longer be typed on a typewriter, but the “happy-to-be-from-zero” minimalist aesthetic has gotten the publication this far through the digital era, and may make it flexible and experimental enough to survive through future publishing evolutions.

Enjoy my entire interview with Holl below.

Why start Pamphlet?

In 1978, during historicism’s backlash, Pamphlet Architecture began as an independent bulletin exclaiming: “we belong to modernity, not postmodernity.” Each pamphlet was a call for an alternative point of view. Each pamphlet would be about one work, a manifesto, etc. For example, Pamphlet Architecture 8: Planetary Architecture by Zaha Hadid was the first publication collecting her work from 1977 to 1981.

Describe the process of selecting entries for an issue in the early days of Pamphlet.

an enthusiastic utterance without a defined audience, the little pamphlets enjoyed the optimism of the indefinite.The experiment of the Pamphlet Architecture series began spontaneously and obscurely between William Stout in San Francisco and myself in New York City. As an enthusiastic utterance without a defined audience, the little pamphlets enjoyed the optimism of the indefinite. With and independence and intensity of spirit, each pamphlet presented a polemic argument, a unified collection of concepts, or a clear point of view. Only the size of seven by eight and one-half inches was a given. Each author was graphically and textually free to make a statement. The pamphlets were “numbers in the dark” in that their authors launched themselves, emerging from obscurity.

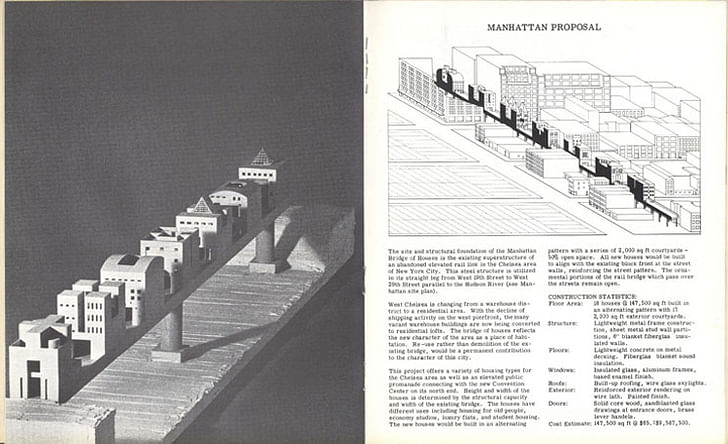

Pamphlet 1: Bridges began this happy-to-be-from-zero stance. Its cover was printed by Mark Mack on letterpress in black ink on black paper and drew scorn from the head of Rizzoli Publications in New York who told us, “It’s impossible to see; we can’t carry it.” The first editions were always hand delivered by Pamphleteers to the three or four New York bookstores who carried them and at William Stout Architectural Books in San Francisco.

How has your role in the publication changed since the beginning, through Princeton Architecture Press picking it up?

To open up and be exposed, to embrace and ebulliently accept chance, is a continued aim of the series. Our initial intuitions and aims have been key to our continuation. Since Princeton Architecture Press took over distribution of the pamphlets in 1985, the series had been able to sustain itself without sponsorship or advertisement. Kevin Lippert and Princeton Architectural Press continue to carry the flame, to raise architecture to a level of thought. Each year we meet together for a day to go over submissions and select the best forthcoming statement.

the series’ maverick hope was to project individual points of view in raw and rough-edged spontaneityHow do you situate Pamphlet in comparison to other architecture publications today?

Freedom and autonomy has always been Pamphlet Architecture’s aim. Stepping out of editorially controlled architecture-magazine culture, the series’ maverick hope was to project individual points of view in raw and rough-edged spontaneity. These are to be statements of independence in contrast to the collective point of view typical of most architecture magazines or internet organizations.

Describe, if any, the effect Pamphlet has had on your own practice.

In 2008 we completed a “Horizontal Skyscraper” in Shenzhen, China which could be considered an outgrowth of experiments began in 1996’s Edge of a city (PA 13). I continue to be fascinated by bridges, just as in the very first Pamphlet Architecture 1: Bridges. You might see the bridges in our Linked Hybrid complex in Beijing somehow beginning in that first PA. Now our Copenhagen harbor gate with “handshake over the harbor bridges” has restarted this month (we won the competition in 2008). Bridges connect. More than just a metaphor, they are open phenomenal experiences.

Is there a legacy plan in place for Pamphlet should you ever leave? As long as Kevin Lippert and Princeton Architectural Press agree to continue the series it will move forward.

For more from Steven Holl, check out "A Dance for Architecture": A conversation with Steven Holl

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

Pamphlet can be chewy and lovely. My fave is Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice and Midgets. But the arrogance of PAP and Holl for scorning the principles bookmaking is the tell to how we, the grubby consumers, are viewed. You're not supposed to be able to decode text or shelter much less interact with either without pain. Both belong to the minds who conceived them and not the sheeple. Please tell me what "raise architecture to a level of thought" could possibly mean. I am too obtuse.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.