As a 34-year old architect, Steven Holl was appointed to a full-time teaching position at Columbia University with barely any completed works to his name, based on the strengths of his publication Pamphlet Architecture, previous teaching stints at Syracuse University and the University of Pennsylvania, and his competition entries. But rather than settling into academia, Holl continued to hone his conceptual formulations to create real buildings that incorporate a signature use of color, a notion of ‘poetry’ within physical places, and a constant refinement of his foundational architectural convictions.

At least, this is the impression one takes away after reading Phaidon’s comprehensive new monograph Steven Holl, written by Holl’s friend, colleague and former student, Robert McCarter. Steven Holl breaks the architect’s work into five primary stages, progressing Each work subtly influences the other, as if every project were an instrument in an ever expanding concerto.chronologically from 1974 to 2014: Archetype/Experience, Anchoring/Intertwining, Luminosity/Porosity, Tactility/Topography, and Hapticity/Urbanity. In addition to including descriptive chapters that act as an overview of each of these stages, McCarter also describes in detail each individual project, whether realized or not. The result is a rigorously intellectual monograph that illuminates Holl’s artistic and architectural growth, resulting in an appreciation of the linkages and throughlines of Holl’s concepts.

Like deconstructing the individual components of a symphony, grouping the work into these five stages allows McCarter to focus on recurring and developing themes in Holl’s canon. A discussion of Holl’s initial conceptualization of the ideal interaction between color and space, featured in “Archetype/Experience,” is powerfully illustrated by the Cohen Apartment project. The Planar House, meanwhile, demonstrates the intimacy and openness discussed in “Luminosity/Porosity” while making subtle visual reference to the dramatic color-play of earlier works. While each is a finished project in its own right, the chronological progression of works, paired with the incisive analysis, creates the sense of organic linkage. Each work subtly influences the other, as if every project were an instrument in an ever expanding concerto.

Chatting with Mr. Holl over the phone from his firm’s New York office, I had the opportunity to ask him about the monograph, his working methods, and a new, unconventional conceptual territory that his firm is currently exploring.

I also try to work from almost a dream state, a kind of intuitive stage, where you’re not trying to make it an a priori to do a creative effort.Julia Ingalls: The Phaidon monograph presents your work as a very articulated series of stages and processes. You begin in the early 1970s without too many physical, real-world projects but with a very strong sense of where you want to go. Early on in your career, you made this comment that “writing about architecture is at best an indication of intentions.” It seems you began very much with only intentions; how much of a role does writing play in your daily life?

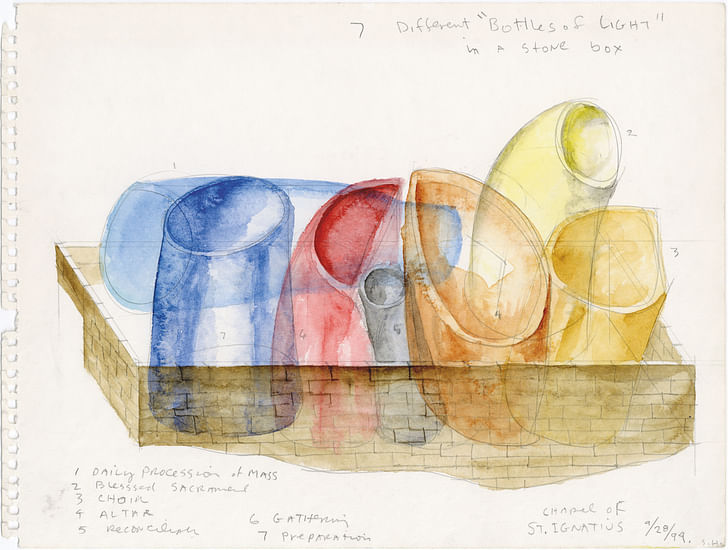

Steven Holl: Maybe it’s in the reverse. Because I also try to work from almost a dream state, a kind of intuitive stage, where you’re not trying to make it an a priori to do a creative effort. Every morning, my exercise, almost like exercising the subjective, is to work a couple of hours, one hour at minimum, to do drawings. Those can relate to a building that’s in process and other ones can be just studies. I will see certain things emerge. Sometimes the word comes first, and then there’s all these shapes, and then I kind of re-imagine the text. And then afterwards, maybe for my classes, I sit and write more descriptive and theoretical propositions. But as a kind of daily process, I’m not working from a template—there’s an openness, there’s a kind of mystery, an unknown that might just appear. That’s actually what’s exciting.

JI: That process sounds very similar to how music is composed. Obviously music has played a tremendous role in your work.

SH: Right. You know that book that Stravinsky wrote while he was at Harvard? It was called “Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons.” It’s a great book because he describes this balance between planning and happenstance which happens to me: it goes both ways. Sometimes there will be an overall plan for a piece of music. I think he once spoke about St. Mark’s Cathedral and the three domes being the structure of a piece of music he was writing. But at other times, there will be these fragments, and he will just collage them together. And they became something more unpredictable. I think in creative work you have to be open to every possible process.

JI: I was struck by how throughout your career, you reference poetry a great deal in terms of creating spaces that resonate emotionally. Later in the book, you’re quoted as talking about how every design should be conceived of as a urban design. So, if every building is supposed to be a blend of those two concepts, do you feel that urbanity is the fundamental emotional experience?

SH: I think not necessarily. I think when you’re in the wilderness, there can still be a architectonic intensity of some kind of compressed element in space. What I meant by the sense that “every project is an urban project” is that with seven billion people on the earth and a real urgency to preserve the natural landscapes that we can, that it’s much more intelligent to conceive of things in relation to human life living in a dense pack, whether it’s in small towns, communities or cities, with the idea of saving as much natural landscape as possible. I’m currently working on a project in Rhinebeck where there was five acres that was going to be a subdivision of five suburban houses, so we got the land and we joined that all as one piece of property. In the middle of the 28 acres, there’s a compressed, exploratory, experimental house. That’s exciting. But that’s—well, that’s a kind of—when I say everything’s an urban project, that’s a kind of strategy to save the natural landscape with a small piece of architecture and re-join the land and stop the subdivision so it’s anti-sprawl, so it has a sense of the urban, but it’s really a rural retreat.

JI: Every few years you’ll publish a book that analyzes where you’ve been and where you would like to go in the future. You’ve written that “theoretical insights derive from the experiences of practice.” Can you speak about what you have uncovered in the last five years? Are you coming to a new idea of where you want to go in the future?

SH: I’m uncovering everything kind of sort of monthly, weekly, daily. I started a project which was—we have like eight things under construction, and they’re all great. But they all need different kinds of attention. Right now, as we speak, I’m drawing a secretarial desk in the theater department of Princeton University. I’m trying to get the details to work and proportions to work so they work well with the room. So that’s not new territory. That’s fulfilling the promise of the work—that project’s been going on for seven years. [laughs] But parallel to that, there’s always new work. And one piece is for the Jessica Lang Dance Company. It’s the stage set for one piece, which we call “Tesseracts in Time.” We helped her conceive of the four stages of the dance piece. all of the arts, the way they intersect and interrelate, that’s much more stimulating than just studying architecture qua architecture.This is going to be premiered in Chicago at the Harris theater on November 5th. And that’s a totally new field, doing these sets for dance. It’s a dance for architecture. That brings up a whole new territory, in a sense. Where light and movement and the passage of another artist, the choreography moving through the architectonic becomes the total experience. I feel that architecture—the movement of a body through space—that’s the instrument of the measurement, space. And you can’t really photograph it. Tomorrow we’re going to go down to Princeton to this new quadrangle that we’re building and it’s fantastic because the space—finally, now—all the elevations are up, it’s topped out, so you can sense the great proportions of this space. This will be the entrance to Princeton University. I’m very fortunate to be doing such an important project. I really put in the energy, I think it’s going to be an incredibly inspiring place. It’s all about the proportions and the light and the subtle play of movement. So, to work in dance you’re certainly seeing it in a different position: I think somehow that’s opening up some new territory. I’m thinking about how spaces could change and how they are made maybe in a more dynamic way from the standpoint of another art.

JI: In the book, you discuss how you feel that a photograph never does an architectural space justice; that it’s much more important to visit it in person to really experience it. With that in mind, and with our discussion about dance for architecture, did you ever see the Wim Wenders film “Pina,” and if so, what did you think of it?

SH: I think it’s very interesting, very stimulating. I love Wim Wenders’ work. I think he’s one of the greats. Pina Bausch was one of the experimental figures: she asked, “What is dance?” It verges on theater. I think that’s also where you find the stimulating aspects—going forward into the future, it’s always that blurred territory between one art and another art that gives you the sort of new territory. We teach a class called “The Architectonics of Music” at Columbia University. I think that all of the arts, the way they intersect and interrelate, that’s much more stimulating than just studying architecture qua architecture.

**Steven Holl by Robert McCarter: published by Phaidon, released on October 26, 2015.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

5 Comments

was there an answer to the question that ends with the word "future?"

/\archinect,looks like you are missing an entire response from Steven Holl

Thanks for pointing that out ^

Missing answer has been un-disappeared

Also, is it just me or are the two paragraphs (Q & A) right before the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art photo, repeated again right after the CIPEA photo?

Thanks Nam, we've straightened things out.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.