The official publication of the University of Utah’s School of Architecture, Dialectic is an explicit extension of the discussions and issues taking place within the school. The annual publication seeks to add nuance and opposing viewpoints to content already being produced by students, culling the best of student work produced throughout the year, framed by an editorial response to the same issues the external architectural community is facing.

We’re featuring the most recent issue from 2013-2014, Dialectic III: Dream of Building or the Reality of Dreaming. Jose Galarza, the director of DesignBuildBLUFF, and Shundana Yusaf, an assistant professor of Architectural History, penned our excerpted text, “Taking the Pulse of Bluff”. At the focus of their piece, and the issue in general, is the history of design-build studios, and their utility as the legacy of Samuel Mockbee’s Rural Studio recedes into the margins of society. In the case of DesignBuildBLUFF, students working for a Navajo reservation must learn to reconsider the basic economic and cultural assumptions on which they build their sense of architectural practice – and harder still, divorce themselves from how inhabitants view architectural archetypes.

"Taking the Pulse of Bluff"

by Jose Galarza and Shundana Yusaf

The design-build program at Bluff is the most prized child of the School of Architecture at the University of Utah. It is the brainchild of the generous Utah architect Hank Louis. Until very recently, Louis both directed and ensured the financing of the program. He has promised to continue to support the program from personal funds for another 10 years as a new director takes over this fully crafted institution for learning by doing. Begun in 2000, Louis’s teaching engine has created enough of a trail, graduated enough architects, inspired enough publications, and generated enough publicity for the school, to merit critical inquiry of its successes and failures.

First Successes

Every fall, a graduate studio of up to 16 students designs a small single-family home for a pre-identified beneficiary of the Navajo Nation in the southern Utah tribal area. They study indigenous architecture and Southwestern vernacular. They read specifications on wood frame construction and building materials. They make working drawings and project management documents. In the spring, these students move more than 300 miles away from the school of architecture, to the remote campus’s small home and namesake in Bluff, close They come to appreciate the expertise of plumbers and electricians, the knowledge of vendors, and the importance of sunscreen.to the Navajo Nation’s northernmost chapters. They spend the better part of this semester converting drawings into habitable space. As the edifice rises, so does a community of cohorts, who can boast hands-on experience in construction, teamwork, successful project delivery (in most cases), budget management, publication of their work, and an incredible amount of physical labor—all upon mere graduation. They come to appreciate the expertise of plumbers and electricians, the knowledge of vendors, and the importance of sunscreen. During the economically dark years from 2008 to 2013, should we be surprised if Bluff graduates got an edge with employers over their peers who opted for the certainties of university environs and the comforts of home instead?

Participants agree that Bluff is an absolutely transformative experience for everyone who participates in it. It has turned idealistic students into professionals not just invested in public interest rhetoric, but with an ability to execute it. It has injected the workforce with architects who know how to activate the power of humble projects over glittering spectacles. Bluff has serviced the profession with professionals capable of taking advantage of the room made by small scale commissions for delicate gestures and sensitive details, the occasion they create for intimate knowledge of the functional needs of the client, and the time they allow for introducing small pleasures and comforts of life into a house. Bluff is a year trainees spend in the apprenticeship of the god of small things.

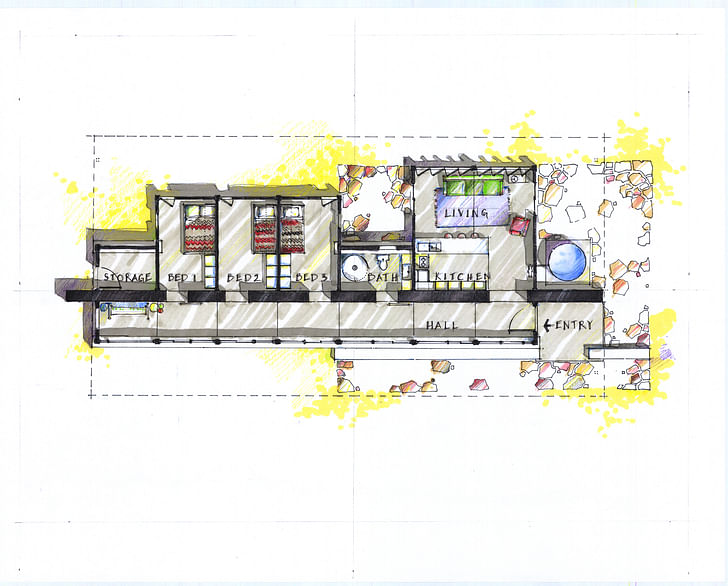

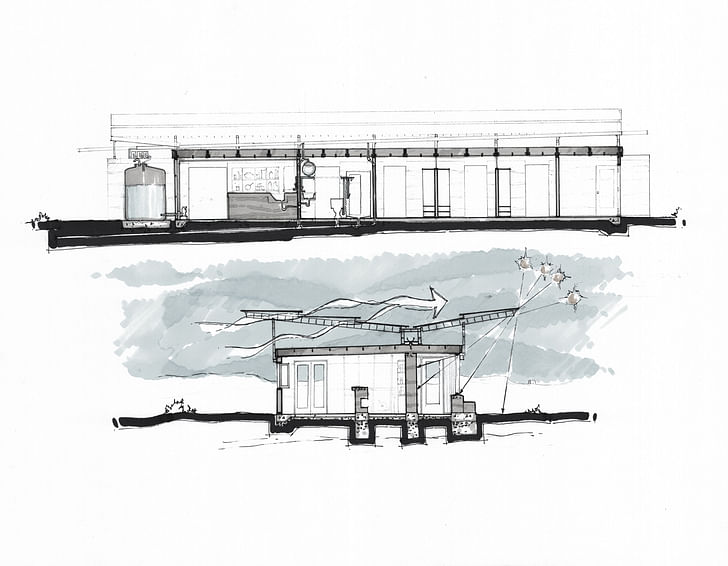

The graduates of this program have under their belts award-winning houses like Rosie Joe. Sitting on the ground with the delicacy of a butterfly poised for flight, Rosie Joe, the first of the Bluff houses, recalls the Navajo tendency to ascribe animal attributes to rock outcroppings and mountains. Its student designers demonstrated the ability to convert passive It has turned idealistic students into professionals not just invested in public interest rhetoric, but with an ability to execute it.energy systems into poetic forms. They delivered a design response for a community with reasonable resources of coal, oil, gas, uranium and copper, but without any reasonable resources left to them to mine these. In this, and in every project since, DesignBuildBLUFF has proved itself in capably translating this historical injustice into a call for sustainable energy solutions. They have oriented every house with a symbolically faced entrance to the rising sun, as is customary among Navajo. At Rosie Joe, they converted the needs of the occupants into a three bed, one bath bungalow with living, kitchen and storage room, all pushed to the north. The south face is fully glazed and a long, single-loaded circulation corridor that doubles as a thermal mass sink. Thick-rammed earth walls on the interior support the passive thermal functions. The team hand-tamped sand and clay from the site into formwork for erecting these walls, producing a red face with dynamic figure and striations in various tones that mimic the surrounding landscape.

Nearly all of the single-family homes built by Bluff students on the Navajo Nation enhance the photogenic ease of the desert panorama. They appeal to contemporary devices of architectural representation.

These single-family homes may have nothing of the neo-classical or neo-gothic styles, but they carry every bit of their anthropocentric attitude to the domus, the Greco-Roman notion of private residence. All of them are well-made machines for living. They are functional, efficient, comfortable, poetic, economical, and environmentally responsible. Each of them helps put and keep in motion the most fundamental pedagogic ambition of Bluff: to raise technê (making) to the status of episteme (knowing). Each of the projects keeps in check the academic preference that has grown throughout the 20th century for the conceptual over the practical. Collectively, the annually delivered homes construct a powerful critique of the notions of space, materiality, and locality in the academy that takes little notice of the capacity of the building industry to realize them.

Bluff is a year trainees spend in the apprenticeship of the god of small things.

Beginning with the historic avant-garde (at the turn of the 20th century), then the paper architects and critical theorists (in the 1970s and 1980s), and arriving all the way to our most recent modeling software and digital fabrication fever (at the turn of the 21st century), our educational system has fixed its attention on the imagined as opposed to real space. These much esteemed interventions in the discipline of architecture have had several adverse effects. They have drawn a wedge between the high and low design opportunities available in the marketplace. They have created graduates alienated from the dominant conditions of the material production of the built environment. The curious animosity between technê and episteme, or making and knowing, has daunted western architecture since the days of Aristotle and Plato. It created a huge headache for Diderot in classifying architecture in his Encyclopédie during a period that Europeans insist ought to be called Enlightenment. Of course, today it is a key “decider” in the fateful ratings of architectural schools. By reinstating what Freud would diagnose as the “reality principle,” in the training of the architect DesignBuildBLUFF has brought into question the social hierarchy within the building industry between architect and builder, plumber and electrician, and so on.

Now Failures

Much more can be said in praise of design-build pedagogy and the fine institution that is Bluff. But if one goes on, one runs the risk of celebrating the asymmetries of power that underpin the successes of Bluff. This case study situates us at a prodigious vantage point. Here we see a struggle between the Navajo’s cosmocentric and our anthropocentric definition of architecture and the architect. The balance is clearly tilted in our favor. After all, it is an interface between one of the poorest, most exploited, and discredited communities in the United States, and representatives of the American academy, one of the most forceful cultural institutions of its day. In an interview, Hank Louis noted that this unleveled playing field was at the heart of his choice of site. He valued it for freeing design from cumbersome building codes and building inspectors with which it is laden in enfranchised communities like Salt Lake City. He was fully cognizant that the opportunity was provided by the weakness of Navajo government. It turned their land into a laboratory for affordable experiments on pedagogy and innovative architecture, in ways not possible under the supervision of the relatively representative councils of our towns and affluent suburbs. Most valuably, it helped students envision their labor on these projects in a most charitable light. For most, oblivion to their privileged institutional position encouraged them to see it as a service to a disadvantaged community that cannot afford professional architects. It is difficult for students to see it as a labor made possible by the generosity of the Navajo people. Their Here we see a struggle between the Navajo’s cosmocentric and our anthropocentric definition of architecture and the architect. The balance is clearly tilted in our favor.hosts let them try out notions of architecture that don’t partake in the spirit of native-built environment. Native architecture thence becomes just an image, a resource for applied ornament. For the students and faculty of University of Utah alike, the Bluff program was not meant for the Navajo, but for the real estate market. Louis tells us that he was mainly interested in preparing graduates for architectural practice in offices like his. It was the simple observation that entry-level architects did not know how to build their designs that led to his establishment of the program. Such are the merits of the invisibility of asymmetries of power. They make the world go round.

We need to educate our students that this community is disadvantaged not because they don’t have architects. Until the middle of the 19th century, building was an essential life skill, like cooking, stitching, weaving, storytelling and throwing pots. Men and women built their houses together. Instead, the Navajo are a disadvantaged community because the dominant culture, of which we all are the beneficiaries and publicists, has robbed them of all their institutions, means of sustenance, and land. They are a disadvantaged people because we have subjugated their spiritual (cosmocentric) attitude to space and time to our modern (anthropocentric) attitude. If this were a problem unique to the Bluff Program, School of Architecture, and the state of Utah, it would not have taken us a decade to see the glaring colonial and exploitative nature of this most cherished of our public interest architectural program. Our blindness to this prejudice is the legacy of the scientific cultural heritage with an old genealogy in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition. It’s not just us. The seductions of modernity, combined with the scornful attitude of the dominant culture towards non-modern, spiritually oriented architectural practices, have resulted in their abandonment by many indigenous people too.

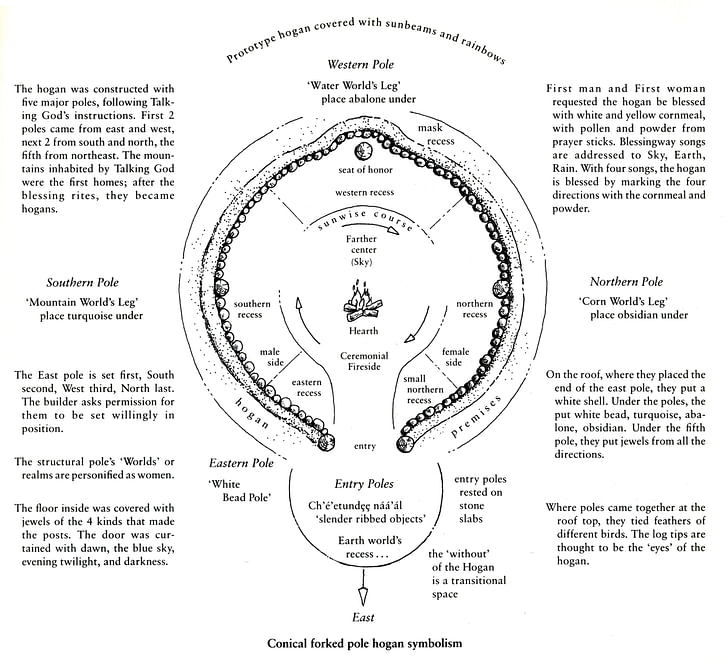

Scientific revolution has replaced native reverence for landscape and earth with modern instrumentality, indigenous gratitude to matter and materials with a longstanding sense of entitlement, aborigine belief in the cyclicality of life and death with teleology, and equality between animate and inanimate beings with hubris. “The fate of our times is Navajo architecture holds a mirror to the closures and dangers of this disenchanted world. It reminds us of modernity’s intolerance to anything that it cannot subsume.characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the disenchantment of the world,” observed the greatest modernist among us, Max Weber. Navajo architecture holds a mirror to the closures and dangers of this disenchanted world. It reminds us of modernity’s intolerance to anything that it cannot subsume.

For us, the house is a rational and phenomenal space. It is a piece of property made of inert materials. It is made pleasing to the eye and the mind by the taste of occupants and the talent of architect. We develop sentimental attachment to it because of the memories we make there. It is the primal site for the production of self, privacy, and normativity.

For the Navajo, the house is not a commodity. It is devoid of windows not for the sake of privacy, but because it is conceived as a return to the womb of Mother Earth. It is both a womb and a grave.

For the Navajo, the house is not a commodity. It is devoid of windows not for the sake of privacy, but because it is conceived as a return to the womb of Mother Earth. It is both a womb and a grave.Regardless of the specifics of design, the plan of the Hogan does not serve to capture surrounding views. It is a model of the cosmos. Building a house is embedded not in the logic of comfort and efficiency, economy and self (though these are not entirely forgotten). It is grounded in ceremonial meaning. Modern education teaches that the juniper or pine poles that support the roof of the Hogan are just that, structurally rational supports, not the Mountain or the Water’s World’s legs. They are therefore disposable. Practical thinking suggests that it is nothing but mere superstition to call the North Pole the Corn World’s Leg, nothing but mere false consciousness to treat the plan as sacred. Devoid of modern infrastructure, it is easy to give the houses east-facing entrances and all our Bluff houses do. It is also easy to make concession to the color of poles: white in the east, turquoise in the south, abalone in the west, and red in the northeast. Alas, some common ground! But it is difficult to have poles in every house—it goes against the sacred principle of innovation. And who cares if they erect the east pole first, then the south, west and northern poles in accordance with the guidance of the sun? Learning by doing should not mean that we have to learn how to build from east to south, to west to north. The east entrance should suffice. It is the beauty of economic wood frame construction that ought to be introduced to the Nation, because that is what we need to learn. Gypsum boards are far more durable and low on maintenance compared to sod, bark, and grass that fill the gaps of the Hogan. This must count as an improvement. And what are we to do with the silly tradition of sealing and abandoning the Hogan upon the death of its occupant so it, like the owner, returns to dust?

It would be shortsighted to dismiss our call for attention to native principles of design and construction—like following the sun and stars, and returning organic material to earth—as romanticism. Far from being the simple disposal process it is today, the “return” of the Hogan provides a link between man and soil, and animate and inanimate existence. It partakes in the cyclicality of life, death, and rebirth. It is an intentional attempt to maintain these links active and alive in the collective consciousness. The native ethos has nothing in common with our salvaging of materials from demolished structures, or recycling milk cartons. The Navajo’s abandonment of the Hogan is an act of respect. It is a reciprocal exchange and participation in the regenerative cycle that is the opposite of the extractive actions of capitalist If our fall from grace after the near destruction of the planet should teach us anything, it should teach us to revisit epistemologies discredited as superstitious architecture.economy. Where we consider organic materials as “natural resources,” the natives revere them as gifts of a benevolent, revered, mother. A comparison of such “environmentally conscious,” “sustainable” architecture steeped in “regenerative” rituals of reciprocity with what today is called Green Economics and Green Architecture, should be instructive. Our “environmentally conscious,” “sustainable” Green Architecture translates all exchanges between us, water, air, and fire, into visible externalities that can be quantified and calculated in monetary value and economic parlance. If our fall from grace after the near destruction of the planet should teach us anything, it should teach us to revisit epistemologies discredited as superstitious architecture.

Much more can be said about the missed opportunities, the closures and blinkers of DesignBuildBLUFF. But doing so runs the risk of dismantling an institution built over years. The question we ought to ask is how the next generation of educators at Bluff can turn learning-by-doing into creative making. What ought to count as creative making? What can we learn from the construction techniques of the Navajo? We also have more fundamental questions to ask. How should we engage a people whose way of life is on the verge of extinction? Currently our interventions, even when welcome, are a form of development, service, and extension of modernity that offsets historic injustices by destroying the historic role of architecture among Navajo people, which is to substantiate and pass on their cosmological beliefs, environmental codes, and the production of community.

This paper, it must be clear, is not arguing for disengagement. It is not recommending leaving native communities to their own devices after we have destroyed almost everything that makes them who they are. Nor it is an argument for reviving dead systems, or preserving existing ones. These are not communities frozen in time. Linguistically and architecturally connected to tribes in Alaska, Navajo have changed and evolved, adapted to droughts and climate change; they have migrated and traded, developed astronomy, geology, and geography. They have moved from pit houses to conical and semispherical Hogans without dugouts. They have borrowed the tipi from the Plains Indians.

We need to rethink how architects should be trained to intervene in informal economies.

But we cannot throw all caution to air, either. We can’t reproduce them in our image, their homes in the image of modern homes, or turn them into inert images of their past glory. We need to rethink how architects should be trained to intervene in informal economies. What roles can they perform in communities that build for themselves? How do we build with the Navajo, rather than for them? These questions are an occasion for the opening up of modernity to alternative modalities of being that will mutate themselves and transform the dominant culture. It is time to think dialectically rather than in terms of us vs. them, or us crushing them into becoming one of us. While history provides wonderful examples in Japan, China, India, and Scandinavia, of traditions enriching the industrialized mentalité, we have little to show for healthy transformations of cultures that have been suppressed as much as the natives. This is the challenge history has left for the next generation of BLUFFERS—a history that could not have been envisioned without DesignBuild.

Also featured in Dialectic III:

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Dialectic III: Dream of Building or the Reality of Dreaming.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.