Besides buildings (obviously), chairs are probably architects favorite things to design. There’s Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chair and Gerrit Reitveld’s Zig-Zag chair; Arne Jacobson’s Model 3107 and Frank Llloyd Wright’s Peacock chair. Today, the tradition continues, with architects from David Adjaye to Rem Koolhaas to Zaha Hadid all designing places to perch. Yet, for all their formal grace and beauty, these chairs rarely break the mold. Invariably, they are designed around an upright individual sitting at a right angle. And, according to Galen Cranz, a Professor of Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, such traditional chair designs just don’t cut it—and they're even harming our health.

Cranz isn’t alone in this—far from it. Experts increasingly argue for new ways to sit and work, hence the rise of bouncing balls and standing desks in office spaces. Still, by and large, ergonomic design remains subjugated by formalism and tradition. That’s because, in part, pieces of furniture aren’t objects in isolation, but rather conform to a host of aesthetic, cultural, social, economic, and even political expectations. In this interview with Cranz, conducted by Heidi Alexander for the inaugural issue of the journal POOL, the architect and designer discusses, among many other things, the importance of producing new, appealing images for alternative ways to position our bodies in space.

POOL is the new student publication of the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at the University of California, Los Angeles. It’s also a platform—or, rather, several platforms—that puts together events and a digital publication, which then feed back into the publication. For the first issue, they focused on ‘the table’, which makes an interview about chairs fitting. After all, the two tend to go together more often than not.

Our featured excerpt for Screen/Print is “On the Ergonomics of Stasis: A Conversation with Galen Cranz”.

On the Ergonomics of Stasis: A Conversation with Galen Cranz

by Heidi Alexander

Galen Cranz is a Professor of Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley. She holds a Ph.D in sociology from the University of Chicago and is the author of the field-defining 1998 work, The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body, and Design. A bonafide expert in all things pertaining to the table’s historically ponderous, socially coded, physically problematic, and seemingly controversial seated half, Cranz offers a uniquely qualified position on the hazards of common seated posture and its associated equipment. Certified instructor in the mind-body and movement based therapeutic practice, the Alexander Technique, Cranz is a founding member of the Association for Body Conscious Design. We spoke with her in April about ergonomics, epidemiology, and the Table’s complicity in the static state of chair design.

You’re still actively teaching at Berkeley?

Yes. I’ll be teaching for another two years.

And then you’ll retire?

I’m thinking of retiring in May of 2018. Nothing is set in stone yet. That is, I haven’t done the bureaucratic, whatever, but I am still teaching and, we’ll see.

And teaching still mostly in the department of architecture?

Exclusively. Yes.

Could you just maybe describe where your interest in the chair began?

It really began because I decided to train as a teacher in the Alexander Technique mid-career, and that was a three-year, half-time commitment. Three hours a day for three years, and that kind of time commitment doesn’t exactly fit in a normal academic program. So, I realized I needed a topic where the body and the environment come together, since I was going to be learning a lot about the body, and since I’m supposed to be an environmental design expert. So, I thought, where do the two topics meet? There’s clothes, there's tools, and there’s furniture. Furniture seemed more architectonic, and the chair seemed like the quintessential piece of furniture. Every architect has tried their hand at designing one. So, I just set out to find out what was known about chairs academically. chair-sitting is now correlated with premature death from heart attack, stroke, and cancerI ran a preliminary seminar at Berkeley and discovered that a fair amount is known about the social history and about construction and style, and ergonomics, but the ergonomic literature had internal contradictions, and that’s what ended up making the study more complex that I thought It would ever be.

There’s a lot going into your description of the various contradictions surrounding the intersection of ergonomics and chair design in the 80’s and 90’s, but I found particularly interesting—I think it begins with the Doug Stewart article in the Smithsonian— this practice of blaming the human body for failures in chair design. You make a statement that it must not be the body but the chair, since the body was here first. But, how pervasive do you feel that idea was, that the body was at fault for failures in chair design?

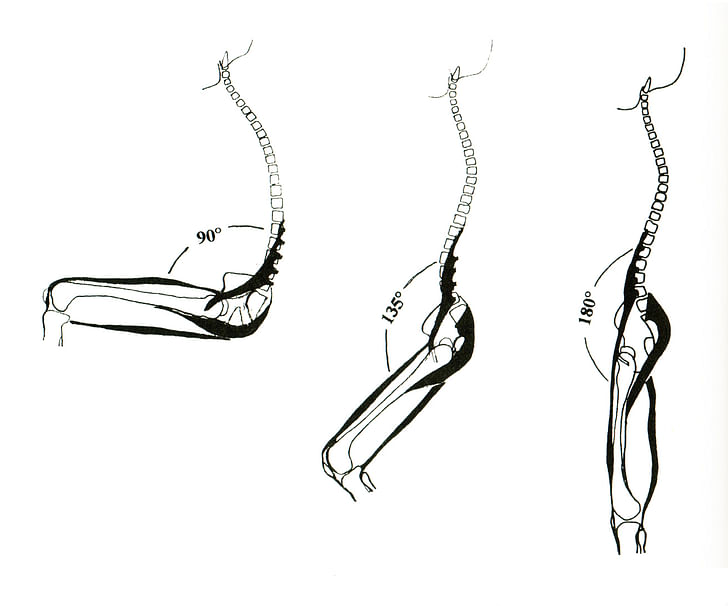

Well, it was very pervasive. The idea that humans are ornery and they just don’t use the chair correctly. Like it’s the user’s fault if they don’t sit far enough back in the seat to make contact with the lumbar support, for example. Whereas in fact, my position on lumbar support is that it’s only needed because of the problem generated by sitting in a chair. The right angle straightens and flattens that lumbar curve, and if you sit at a perch rather than a right angle then suddenly your lumbar curve comes right back in by itself.

The conversation on support in general is really interesting, and the struggle within ergonomics to release the idea that we need support, or that support is a solution. The contradiction between support as both solution and problem.

It’s a debilitator. You support something, you stop using something, and then you get weaker.

It seems to be a point with implications far beyond the chair in terms of how we design in general.

Yeah (laughing). I think so. Thanks for noticing.

You talk about a shift in early postmodernism away from the application of pure geometries and clear intention in chair design and the coincident development of ergonomic applications as producing a design environment which failed to unite the formal and aesthetic ambitions of the designed chair with emerging ergonomic approaches to office furniture and culture. Do you feel like that disunion has resolved at all in the intervening years?

Well, to some extent. Like, you know, the Aeron Chair is very much appreciated for the sheer pellicle, and that’s a symbolic and visual appreciation as much as any kind of functional, comfort-based appreciation. Historically, there has been a split between furniture for the home and furniture for the office. They diverged. Today, you still don’t select an Aeron chair for your dining room table. You don’t have a set of six or eight Aeron chairs. So there is still this basic split, but there are hints at coming together in that, as I said, people aesthetically like the Aeron chair.

You document a significant disconnect between the scientific aspirations of the field of ergonomics and its limited ability to properly evaluate itself due to a lack of reliable observational methods, be those electromagnetic, reportage, or otherwise. I found the apparent unwillingness within the field to accept and respond to the largely negative correlations that were coming back, regarding relationships of static comfort and either productivity or support, pretty startling. It seems a similar disconnect persists regarding the relationship between passive comfort, and overall human health and longevity, in common architectural application of ergonomics. Let’s say for example, in maintaining human thermal comfort through the support of energy-intensive building mechanical systems.

Well, chair-sitting is now correlated with premature death from heart attack, stroke, and cancer. Without muscular firing, the pancreas no longer produces an important enzyme. It’s called lipase, and it’s needed by the liver to deal with fats in the bloodstream. Without lipase, undigested fats go into the bloodstream, setting us up for earlier cancers, heart attacks, and stroke than we would get otherwise. So people are scared now about sitting more than three hours a day, since that’s what the epidemiological studies tend to suggest: that three hours a day is safe and anything beyond that, we start increasing our probability of premature death. So now, even we’re producing stand-up and treadmill desks. It’s not enough even just to stand, you need to be walking a little bit.There’s an inherent conservatism in culture.

While the table may or may not have a similar complicity, it’s certainly difficult to think about working in chairs without sitting at tables.

The obvious connection that I see is, if you’re going to do chair reform, you’re going to need to move from the right angle position to perching. So you’re going to need a higher work surface. By table to you mean work surface, more generically, or do you mean only what we know as a dining room table. Do you mean desk?

We’re looking at all types of tables. Primarily, the conversation is focused on what we more traditionally think of as a table, be that a dining table or a desk, but yes, the work surface.

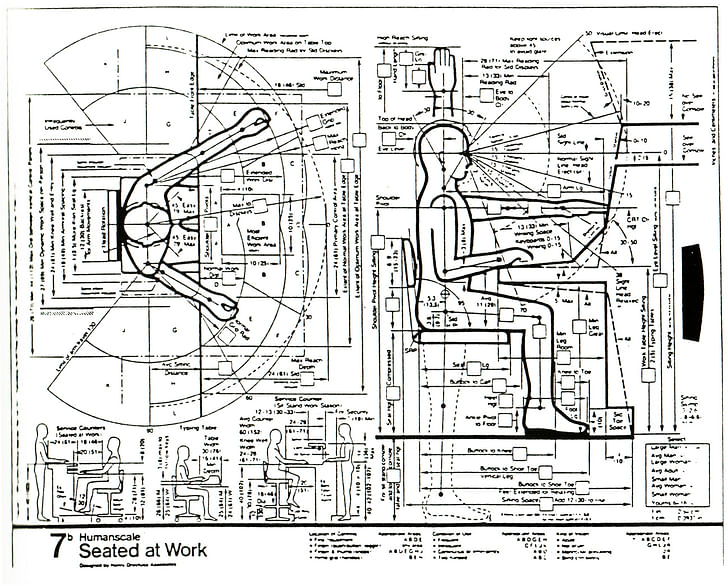

The consequence of the epidemiological studies about the association between mortality and number of hours seated—the consequence of that is that you need to stand, but we know standing is tiring to the legs. The real solution is that you need movement, so you enter the world of hydraulic, or electric, or mechanical, adjustability. Also, there’s the issue of, should you work on a flat surface? Before a certain historical period, work surfaces were sloped, because to read on a flat surface is really hard on your neck, if you’re going to sit up straight and look down, it’s really hard on that top joint. Instead, what people do is round their spine to get down to the work surface.

So the table needs to be redesigned just as much as the chair needs to be redesigned. The table needs to be of adjustable height, and the work surface should be able to slant for reading and for writing. Now for computers—obviously we’ve got the monitor as an additional piece up there. And then the keyboard, some people say should actually be quite far down: that the arms shouldn’t be at a right angle. The hands should be at more of an open angle, and maybe the keyboard is even split. So you can see how there is no perfect posture…You know, one guy said, “The best posture is the next posture.” We’re designed for movement, as a species. So if we’re gonna sit up at our perching height, then we’re going to have to be able to move the chair. Maybe ideally, the chair and the work surface should cooperate in some kind of slow moving transformation, undulation. You know, I think of it as a sort of tai-chi work station. This kind of really slow moving change would mean that the joints have different stresses on them in the course of an hour and in the course of a day.

So there’s a very strong link between the sitting surface, the resting surface, and the work surface. They are locked. And it’s one of the reasons it’s been so hard to make chair reform. Once you get people to realize they need to perch a little higher and have an open angle between thigh and trunk, then they need a higher work surface and, “Oh, that’s too hard! We can’t change both the chair surface and the work surface all at once.” And so we do nothing. It shows how cultural aspects are interlocked, and that’s why change is so difficult. There’s an inherent conservatism in culture.

I guess my question regarding the misapplication of ergonomic logics in sustainable design and furniture design is also tied to the point you raise, that to get change in furniture design, due to status-based factors in furniture choice as well as capital flows, one fundamentally has to induce the stylistic acceptance of the more monied class first. There’s a certain trickle down effect in furniture design.

There’s a power and status thing going on, you don’t get change unless you get the most powerful people to start the change.

It seems that the opportunity for change to occur through that mechanism lies in producing designs that make it both intelligent and sexy to have these things. On the one hand, creating high consumer appeal for a body-centered design, or for sustainable architecture, or other environmental aids that contribute to our ultimate physical and cultural health. But also giving more weight to the fact that the need for aesthetic pleasure in these designs is a real determinant of their capacity to enact reform.

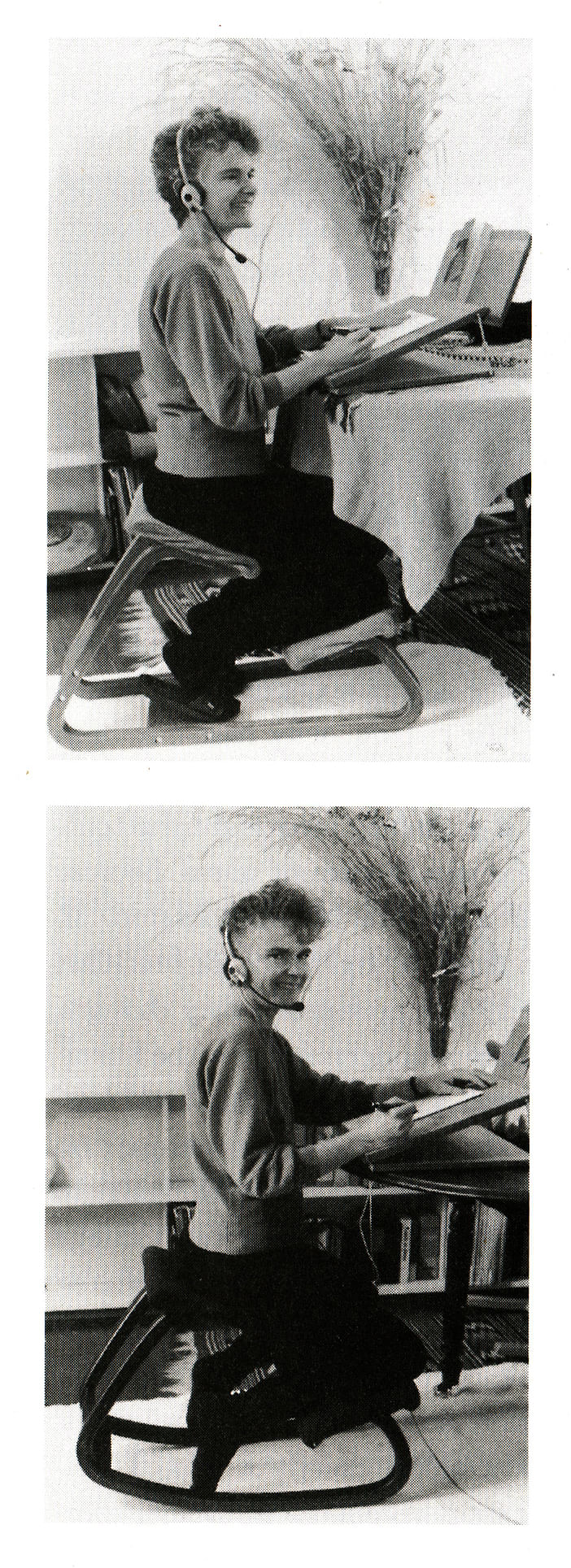

Yeah. It has to look good. But it will only look good to people who already know the advantages of the new system. So education, and not only verbal education, but of course, showing new imagery. Showing the hip person at work in this comfortable, flexible, changeable environment. Image is very important.

When you see images like those of yourself in the Balans knock-off with rockers—when you see a chair like that, you can’t help but ask questions. Or when you go to sit on a chair like that for the first time, it’s instructive in and of itself as an object. You’re forced to approach it in a different way.

Yes.

Your book speaks broadly and in significant historical detail to the communicative quality of furniture in general, and chairs specifically. In architecture, chair design seems to have taken on a largely rhetorical dimension, which is perhaps somewhat hermetic to the field. Certainly architect-designed chairs retain their broader socio-communicative characteristics regarding taste, style, class, gender, etc, but they’ve also become a way for architects to communicate ideas regarding the work of architecture.

the architect has to think it’s cool. Because architects are very influenced by how they imagine their peers respecting them.

Yeah, so architects have to be persuaded that this is cool. Internal to the professional culture, they have to be persuaded, and then you can work on the public. Or maybe you need two campaigns, one for the public and one for design culture simultaneously, so that architects have support culturally, with clients. Clients have to understand, or they ask: “Why are you telling me that I need an office with all this funny movement?” So the client has to be educated, but also the architect has to think it’s cool. Because architects are very influenced by how they imagine their peers respecting them.

They also need to accept the fact that they have agency in determining what’s cool.

They do.

It’s a frustration amongst students that there seems not to be a tremendous amount of emphasis on human beings, much less the human body in architectural culture at the moment. It’s very focused on formalism.

Digital delirium, a friend has started to call it: the forms that are generated with the digital capacities that we now have. Yeah, so the social has taken a back seat, and it will have to come back. It will just have to, otherwise the profession will die of irrelevance.

Do you see any particularly promising developments in terms of body-conscious design in architecture?

Some people are fiddling around with more humanistic, body-centered, democratic office design. That’s a good sign. In local grade schools here, parents are setting up schools with little standing desks for kids. That’s a good sign. In the quest to save money, some of the corporate offices like AirBnB have turned to hot-desking, where you don’t have a regular desk but you come in and you pick your workplace for the day, and those are often stand-up spaces. So, in some ways, real estate value is making people rethink office space and make it less sedentary. And then urban design people have figured out that because people need to walk for health means we have a justification for making streets more beautiful, more interesting. So urban design, school design, office design—these are positives that are happening despite the architectural profession.

It seems that developments in real estate and the economic motivations for standing might be the most likely to succeed of all of those.

Well, or schools. People do care about the welfare of their kids.

I have to say that halfway through reading your book, I had to sit on the ground. It really gets under your skin.

There is a warning at the front of the book. It says: “You might find yourself getting more uncomfortable.”

Well, it was very effective.

Want to find out more about Cranz's work? Take a listen to our podcast interview with her for Archinect Sessions One-to-One.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Pool's first issue, "Table".

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.