Forget, if only for a moment, what you know about Denmark. You will forget

such things as Hamlet, Bodum carafes and French presses, Christiania hash,

Niels Bohr, Little Mermaids, and licorice. And, by all means, forget what you

think you know about Denmark. For the architecturally-inclined, this

means suspending your own knowledge of history. This means suspending any idea

you may have about modern and contemporary buildings like Arne Jacobsen’s SAS

Hotel, C.F. Møller’s and Kay Fisker’s Dronningens Tværgade, Jørn Utzon’s

Bagsværd Church, and Henning Larsens’ Opera House; or even the Scandinavian

neo-Baroque Odd Fellows Palæet and the neo-Gothic functionalism of P.V. Jensen

Klint’s Grundtvigskirke – yes, we all know about Denmark’s rich design

heritage. But take a walk along Islands Brygge, at the University of

Copenhagen’s new, sparking campus, and you’ll see something achingly

contemporary. Is this a liability? Go to Copenhagen’s Kastrup Airport, where a

brand -new sign reads: Something’s modern in the state of Denmark .

And to stay loyal to the Hamlet theme, I am suddenly reminded of a sign I read

in the New York Subway only a couple of months ago: Risk, perchance to

Dream (yet another Hamlet reference). This word – “Risk” -- is

fascinating as it conjures Milton Bradley board games as well as financial

skulking that would make Ivan Boesky or Gordon Gekko grin with fatherly pride.

In this reviewer’s mind, risk implies savvy. It implies, as critic Michael

Speaks would put it – design intelligence. Yet what does design intelligence

mean? Does it imply an architect’s tacit and cursory understanding of the

movement of global capital across the world’s physical and virtual

infrastructures? Or is it something more?

On an unusually warm August day in Copenhagen, I had the opportunity to raise

these issues. With Bjarke Ingels. Yes, that Bjarke Ingels. If you

forget what you know (and what you think you know) about Denmark, you will

instantly remember Bjarke. He’s OMA-bred (like many designers we like to keep

tabs on). Along with Julien de Smedt, Ingels was also a founding partner of

PLOT, arguably one of the most exciting (and successful) firms to come out of

the post-Rem detritus. And now, after PLOT’s much talked-about dissolution,

there’s BIG. That stands for Bjarke Ingels Group, an architecture practice

that demands attention. What follows is a transcript of our conversation.

[Enrique Ramirez] You’ve been at your Nørrebro office for almost a year, and as

I am walking through your studio, I cannot help but notice the way your

practice uses iconography. Was this always a conscious part of your work?

[Bjarke Ingels] Yeah, I would like to think so. But it was never as

calculated as people would think. A while back, I was in Shanghai. PLOT had

just split up. I knew I was going to continue my practice. I was in the

process of finding a new name, and it was kind of hard. I had this idea of

giving the office a name that wouldn’t be my name. We had used “PLOT” for 5

years, and now we had to find another catchy name. So the thing I liked about

the name, Bjarke Ingels Group, was that it had the word “group”, as in “group

effort.” It was an acronym that was funny, at least in the Danish context. I

mean, we are a tiny country, and of course, BiG sounds a little bit

pretentious.

Having the right initials did not hurt.

(smiles) Of course not. But, there’s more. So, in Shanghai, we

discovered that a sign we had done for a client actually looked like the

character that means “People” in Mandarin. We then realized that the Mandarin

word for “Big” looks remarkable like the word for “People”, but with a line

drawn across it. It felt like destiny.

I won’t be the first to tell you that this is simply amazing branding.

It’s interesting to see branding fully integrated into the firm, in terms of

web design, the building, everything

Yes, but I think these things always occur accidentally, or maybe

during brainstorming. It’s really hard to find a new name, but once I found

out there was this weird relationship between the Mandarin script, our

company’s name and ideas, well, you can imagine our excitement.

But that word, “excitement” really describes something really compelling

about BIG. If you look at your work, your projects, there’s this incredible

mix of unquestionable legibility and clarity, and outright giddiness. You look

like you are actually having fun.

But it’s very serious. Like Monty Python would say, “we are serious

about being funny.” But there is some truth to that, you know. Having fun is

of course good for us. But it’s also important for the client. Having fun

means creating a climate where everybody is willing to push themselves, to go

a little bit further.

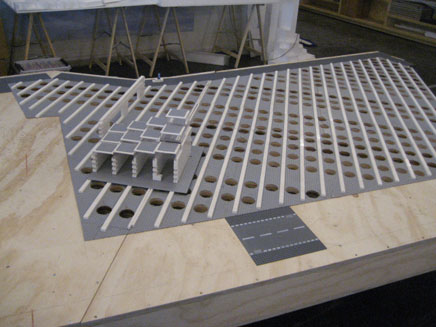

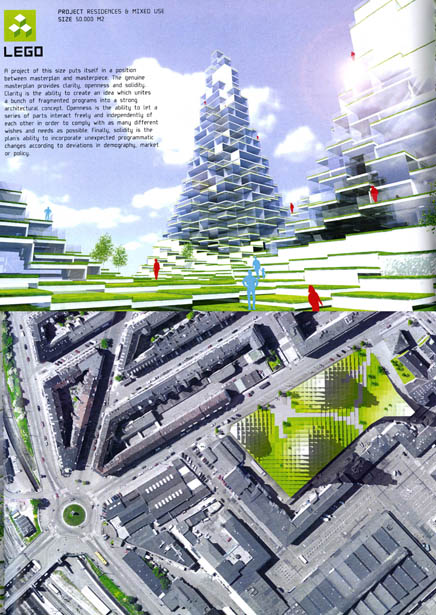

Indeed! Like this Lego site model. Can you describe it?

It was a competition for a mixed-use development. Well, essentially

it’s this very large development, 40,000 square meters, based near the

Copenhagen central station. The client required a 400 FAR, so this meant we

had to investigate different ways to increase density. Doing that is a

struggle. People here are skeptical of high rises … everything above 20 meters

is immediately “un-Copenhagen.” If you analyze the skyline here, you will find

out very quickly that a 400 FAR is near impossible without breaking the height

limit. I think we were facing an age-old problem, and therefore had an age-old

response. Until the beginning of last century, architects could actually

imagine really cool and interesting projects, but with demands of production,

economics, etc., it seemed that the only solution was a modernist box. I know

this may seen simplistic, but bear with me. Copenhagen is known as a city of

towers. What if you could combine the two things, the Copenhagen tower and the

modernist box, seeing their combination as an opportunity instead of as an

inhibition? Instead of starting by doing something unimaginative, instead of

trying to squeeze something irregular into a regular grid, we constantly

experimented with creating various any shapes. So in 3dMax, we made a carpet

that we pulled over the site, creating a low-resolution blob with peaks and

valleys – something very much like those pin shape puzzles you see

everywhere.

We like this project very much. On the ground floors you have parking, sky

lit shopping, becoming three floors of offices, becoming housing. It also

features this transition from the ground to the towers – a transition from the

arena-like public areas to the more private offices in the towered peaks.

And why are you building the model out of Lego pieces?

Perhaps it’s a tribute to modularity? Or a homage to the building

industry? Like our logo, we had another lucky moment. We found out that if we

build our context model in 1:500, we would essentially be matching the scale

of a single Lego figurine.

So we built the context model using this software you can download from

Lego. When you’re done with the model, you click “submit” and you pay. They

send you a box with a picture of your Lego model. So after we won this

competition, we got the idea to get Lego to sponsor the construction of a

model scaled to a Lego person. So they donated 220,000 Lego pieces. The

results will speak for themselves.

But at what point did the inspiration to use Lego become evident? At what

stage?

There are a lot of Copenhagen things – Danish things in this project.

We were actually thinking about Jørn Utzon, especially his idea of the

additive, that you could create any possible form out of a series of

industrially produced elements. This is basically the same thing. But we

wanted to take it further. We wanted to use two Danish icons, two things from

our childhood and our education – Utzon and Lego – and take it to extremes.

But it seems to me that a perfect example of BIG’s approach. Here we have

a design problem, and yet you have the capabilities to negotiate with

companies like Lego. Do you view BIG more like a consultancy than anything

else?

We just try to keep things interesting. A project becomes interesting

when it is an experiment. And once you formulate the plot, the starting

concept, what a project is about, it becomes infinitely easier to do it. It

sounds silly, and you are probably saying. “Duh!”, but you would be surprised

how far one can get along by treating a design problem like an experiment.

You start opening your mind to new possibilities. And this means that when

things become too rigid, you revisit the problem, and tweak it. You change the

parameters. And I think that at this point, the decision making process

becomes much more sound, and much more fun. So with this project, we never

began with the idea of a Lego branding exercise. Only when we started talking

about the modularity of Lego bricks, the popularity of the Lego brand, and the

fact that we are, first and foremost, a Danish company, then things began to

get interesting.

But your idea of keeping things interesting must certainly be related to

your own experiences as a studio instructor. The idea of “ecolomy” was

certainly a big part of your advanced studio at Harvard Design School, can you

tell me a little bit more about it? What do you mean by “ecolomy”?

Well, it’s a little different than Koolhaas’ use of the word in

“Junkspace,” I would like to think of “ecolomy” as a particularly Danish

thing. It began here in Copenhagen. We were working on an energy-related

project for the city. It was around the time of this conference about

consensus. The conference organizers invited all types of economists, and

together, they began to prioritize all of the world’s economic and

environmental issues in terms of price. People were appalled at the idea of

putting a price on the environment. But the sad truth is that if you don’t do

it, it won’t have any value to anyone. Whether you want it or not, you will

actually priortize things against each other.

The idea of ecology and economy, or ecolomy, offers a different spin on

this problem. It is a way of preventing a “good versus bad”, “philanthropy

versus capitalism”, “economy versus ecology” dichotomy. Looking at things in

these absolutes is quite harmful. Ecolomy is thus a way of thinking and

working. It goes beyond looking at things in terms of solely expenses and or

investments.

So it’s a systemic approach?

Exactly. And we try to incorporate it into our work. Our projects

continue to incorporate ideas about sustainability. But we don’t see

sustainability as this pious thing. It doesn’t have to hurt. In fact, our

choice of materials and systems for our buildings actually help reduce

maintenance costs and allow for longer life cycles.

Do you see this as a paradigm shift for architecture practice? Can you

elaborate a little bit on “ecolomy” and Danishness?

I think the Danishness of BIG’s practice, which I am fairly conscious

about, is a reaction to the egalitarian-ness of Danish culture. Everyone is

supposed to be heard. There is no culture of majority. It is a culture of

consensus, incorporating concerns of everyone. Traditionally this has lead to

a case of mediocrity, as evidenced by the fact that all Copenhagen’s buldings

are the same height. No extremes. Essentially, it creates a lowest common

denominator. Architecturally, this means the repetition of common square

boxes.

BIG is about finding ways to empower ourselves as architects and urbanists.

It is about thinking how all these concerns -- site, program, form, ecolomy --

can be wielded as a power. There is a zen koan that talks about making the

force of your opponent your own force. In terms of our project, we do not

compromise. We take all the demands and insist of solving every single one of

them. We think that, as with the Lego project, the result is infinitely more

adventurous than plain housing slabs. BIG is not about the power of

architectural genius. We explore the idea that collective interest is a viable

design power.

Perhaps this explains your interest in both public and developer-based

models.

I think so. We’ve had great success with our Kløverkarren project. We

actually had to act as a developer, entering into a contract with the City of

Copenhagen, to finalize this project. We designed a superstructure along the

perimeter – a 3km long building that surrounds a network of sports fields.

But this is not easy. I have been traveling for the past six weeks trying

to sell this project. And at this point, you begin to see how being an

architect means that you have to be a little bit of a politician. You become

too familiar with codes, laws, and how they can be limiting.

Do you think that architects can use their expertise to change these

laws? Do you see a need for BIG to go beyond a developer model and enter the

realm of advocacy? How complicated an issue is this?

I would like to think of it as being rather simple. When it comes down

to it, the mechanisms behind all these systems – legal or institutional -- are

simple. I recently read Ray Kurzweil’s book Singularity is Near , where

he defines complexity in a very nice way: complexity is the ability to convey

the maximum amount of information with the minimum amount of data. So

complexity is a form of simplicity. BIG is about the complex, not the

complicated. There’s a difference. Einstein said something like “Don’t

simplify things, make simple things.”

So for a designer, simplicity can be this very subjective thing. One

person’s complexity is another’s simplicity. Take the Lego project, for

instance. In one sense, the idea of using Lego bricks seems rather simple or

facile. But in fact, it entails a very nuanced business savvy – an

appreciation for the corporate sphere.

Perhaps. Have you seen ICON magazine? Our manifesto is entitled

“BIGAMY.” It’s about the ability to have things your own way, on your own

terms. It was a manifesto for this essentially Danish approach. It was our way

of saying fuck the budget, fuck the rules, fuck the context. You do not have

to define yourself as a revolutionary against the establishment. If you decide

to be a radical against someone else, essentially you are a radical in

reverse. So perhaps there could really be something radical about pleasing

everybody.

Do you see any opportunities to explore this idea in the future? Do you

think that this is something worth negotiating in an academic setting, or in

professional practice?

Well, there may be an opportunity very soon, at the Architectural

Association in London. I’m talking with people about teaching a studio there.

The topic would be the 2020 Olympic Games in Copenhagen – a hot discussion

topic there right now. It would be an opportunity to further press the ideas

of ecolomy, sustainability, consensus, complexity. You can pass legislation

such that all large-scale buildings should have low energy consumption, you

can even mandate zero-energy buildings. But this will never change the fact

that Copenhagen has already been built. To really think about sustainability,

to think ecolomically about it, you need to exploit the syntheses of programs

at a massive level, at the urban level. This means integrating the flow of

infrastructures into a viable design strategy. In other words, what if all

investments for the 2020 Olympic Games can be marshaled to make Copenhagen the

world’s first 100% ecolomical capital?

That seems daunting.

But it’s worthwhile. You have to look at things anew. Take new

approaches. Once you have done that, great things will happen.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

19 Comments

great timing! the BIG event at Storefront last night, coinciding with the release of this interview...the timing is especially useful because the focus of last night was beer drinking and casual architecture model perusing. this interview adds significant content to the overall experience. Thanks Enrique, great intro and questions.

Bjarke Ingels will be talking about his work on Thurs night in conjunction w/ the Storefront show:

IN CONVERSATION: Bjarke Ingels and Mark Wigley

Thurs, Oct 4

Van Alen Institute

6:30pm

http://www.vanalen.org/events/BjarkeIngels_MarkWigley

Once again an Architect who is getting into development and sees this trend as the way forward...

As has been argued in forums and elsewhere it certainly gives the architecture a "greate rlevel of control" at least in terms of development of a program....

It will be interesting to watch and see if more and more follow this trend...It is at the least an opportunity for architects to make more money, out of any project.

Also,, i was struck by the answer below.

"Perhaps it’s a tribute to modularity? Or a homage to the building industry? "

He is not even sure why they did it..Symbolism without meaningful intent...

Is that even possible.

Fascinating interview, Enrique. Ecolomy....I will have to bookmark this for my thesis research.

great interview enrique... i just returned from the ifhp world congress in copenhagen on saturday... while i was there i had the opportunity to take a quick tour of the VM houses with one of the architects from PLOT/BIG... i also saw "the mountain" which is under construction right next door... i can't recall his name, but he was a great guy... i really enjoy their work... there is a lot of great stuff happening in cph right now.

actually i think that is him in the long sleeve gray shirt in the center of the picture of the big model... he lives in one of the VM units...

I would be interested in the financial success or otherwise of Ingels practice. We never hear the details of money, turnover, investment, return, or financing in regards to architecture practice in general.

I am wondering how BIG's approach differs from traditional practices in terms of their revenue stream.

I appreciate BIG's approach, but I wonder whether it is built on a genuine unique business model that is sustainable and duplicatible, or whether Ingels' practice has some other financial support that allows the degree of experimentation that is seems to indulge in.

Dont get me wrong - I believe in architect as developer - and BIG is doing some amazing work. I want to emulate them, but I want to know if it can be done and how...

there was an article about PLOT as a business and how close they were to going under, how they had no commissions and sort of made their own (interestingly Ando did this once too, and Steven Holl tried but failed)...someone here might recall the link. it was interesting cuz they are honest (seeming anyway) about their business and how it has gone so far.

unique? i don't know. maybe. certainly they are trying to do new things and willing to go whichever way necessary to get there...that is maybe what is new. i find them also quite fresh cuz they don't seem to have a feeling of entitlement, of deserving the work they do. they work to get it. that is impressive.

Well these are the details that I think are important. I would be interested in seeing that article on PLOT.

I can understand a young architectural practice inventing its own 'commissions', briefs, and projects as an intellectual and marketing endeavour - this is commonplace and serves a variety of purposes. MVRDV did/do it, Koolhaas did/do it etc, etc. Whatever resources it takes to do this are written off in terms of the publicity and knowledge it brings in.

What I am trying to figure out is whether BIG are operating from a different [maybe not unique] business model, and if so what is the basis of that model and is it successul, or underneath it all are they a 'regular' practice with a whole lot more marketing and branding savvy.

Again, I am a LARGE fan of BIG, and I want them to succeed.

I do love these archinect features, always pushing the nose of architectural discourse. Thanks for this.

Interesting too I might add the slant of discussion after, more about the financial/business side of BIG as a concept for practice. Great stuff

more like this please.

IN CONVERSATION: Bjarke Ingels and Mark Wigley

last night at the Van Alan Institute (thanks for the heads up, it was an entertaining and informative event).

he's wearing a kraftwerk t-shirt

I wonder if this "Danish" model is exportable to other European nations or other nations generally. Certainly in DK, "ecolomy" makes perfect sense: the Danes are hyper-sensitive to environmental issues. It makes sense elsewhere, too, but would such a model be as well-received in, say, Shanghai or Sao Paulo or Philadelphia? One can only hope...

Risk was produced by Parker Brothers, not Milton Bradley. Hail the Instant Icon.

Vado .... both Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers are wholly-owned subsidiaries of Hasbro. Hail the instant icon indeed.

yes but my risk experience predates the hasbro buy out.

touché, Vado

So, no further comments on the financial and administrative structure of the BIG practice? - still waiting....

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.