Two and a half years after the initial outbreak of COVID-19, the U.S. architectural profession has emerged from the global pandemic in a stronger condition than many could have expected during the depths of 2020. However, many questions remain unanswered on how the pandemic impacted the architectural job market, firm operations, and the design process; questions which deserve scrutiny in the interests of avoiding future economic pain, and building a more resilient profession. In search of answers, we speak to three firms in differing parts of the U.S. to hear their reflections on how the profession fared during the pandemic, and where it goes next. To understand how these unique experiences fit within a national picture, we also speak with AIA Chief Economist Kermit Baker, who reflects on a deeper supply-demand issue across the profession.

When we began our journey exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the architectural profession, we did so with a litany of questions; some born from curiosity, others from bemusement.

How did heavy industry job losses in 2020 lead to a shortage of job seekers in 2021? How did the seismic economic crash of early 2020 not leave the profession in ruins as it did in 2008, despite the 2020 recession being multitudes worse on-paper? How did the architectural process, often a collaborative, situational act, survive a mass migration to remote working? What happens next?

We weren’t sure what answers would emerge. However, with the emotional fog of the pandemic lifted, and with an ability to look back at a turbulent two years from a position of relative calm, we were confident that now was a good time to ask.

Major economic stresses, the pandemic included, have a tendency to exacerbate weaknesses in an industry, be it financial models, labor models, or operational models. In the heat of battle, we are required to make short-term, tactical decisions to address these weaknesses. But it is only when the dust has settled that we can look back, see the forest for the trees, and make long-term, strategic assessments on what worked, what failed, what can be retained and built upon, and what can be reformed and replaced.

We were also conscious that, of the answers we extracted from our conversations with industry figures, not all would tell the same story. Throughout the wider economy, the pandemic’s economic impact was far from equally distributed. The fortunes of an Amazon or Zoom executive through 2020 and 2021 fared significantly stronger than those of a restaurateur or an airline pilot. In fact, the pandemic saw one of the largest upward transfers of wealth in human history, with the world’s ten richest individuals doubling their fortunes while the incomes of 99% of global earners declined.

Zooming into the architectural profession, the disparity in fortunes becomes less dramatic, though it doesn’t disappear entirely. As American Institute of Architects (AIA) Chief Economist Kermit Baker told Archinect, the economic impact of the pandemic varied depending on a firm’s sector speciality. Despite the pandemic causing an initial stagnation in residential design services, for example, the pandemic era also saw some of the strongest housing starts numbers in the past decade. While this performance can be attributed in part to an ongoing chronic housing shortage across the United States, the Federal Reserve’s decision in March 2020 to reduce interest rates to “essentially zero percent” is also pertinent, given that a decline in interest rates has historically served as a short-term catalyst in the demand for new housing.

“The dichotomy between residential and non-residential work has been fairly significant,” Baker told us. “From a firm perspective, if my practice specialized in single family residential, custom residential, or even multifamily residential, the market has been incredibly strong. It stagnated for a couple of months [at the beginning of the pandemic] but then came roaring back.”

The dip was sudden, severe, but for most sectors, short lived.

Understandably, renewed confidence in housing construction did not translate to other typologies. While ‘home is where the heart is,’ a cloud of uncertainty in the heat of the pandemic led investors and architects alike to question if there would indeed be a future for office buildings, hospitality complexes, or airports, in the same volume, scale, or architectural form as before 2020.

For Baker, data suggests that non-residential sectors did indeed decline, though not as much as initially feared, and not as severe as was seen during the 2008 economic crash. “We saw declines in construction spending both in 2020 and in 2021,” Baker told us. “The decline was not tremendous, but still in the mid-single digits. That is now starting to regroup in the middle of 2022, at the same time that the residential market appears to have crested.”

The economic recovery of both the profession and the broader economy from the shock of the pandemic is miraculous when we reflect on how 2020 began. From its peak in the fourth quarter of 2019, the U.S. economy contracted by 19.2% through the second quarter of 2020; the worst crash on record. By comparison, the largest contraction of the 2008 crash was 8.5%, occurring in the final quarter of 2008. Between the final two quarters of 2020, however, U.S. GDP rebounded at a record average of 18.3%, which some experts attribute to an enormous legislative response to the pandemic including the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan.

“The economic downturn on the industry during the 2008 economic crash was much more significant than this one,” Baker told us. “In 2020, we effectively flicked a switch and closed down a large segment of the economy. The dip was sudden, severe, but for most sectors, short lived. Even on the non-residential side, demand has come back faster than we would have expected, and never got as weak as we would have expected.”

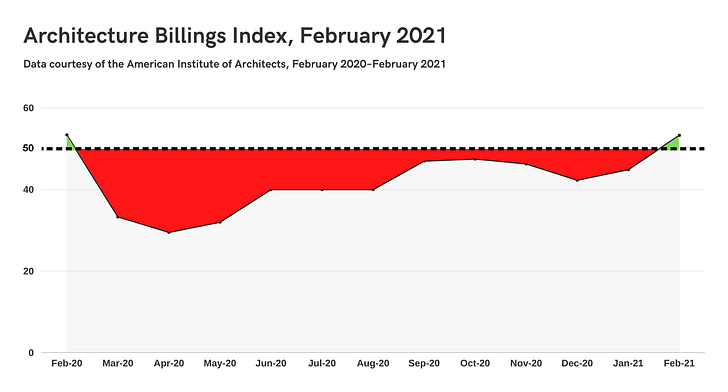

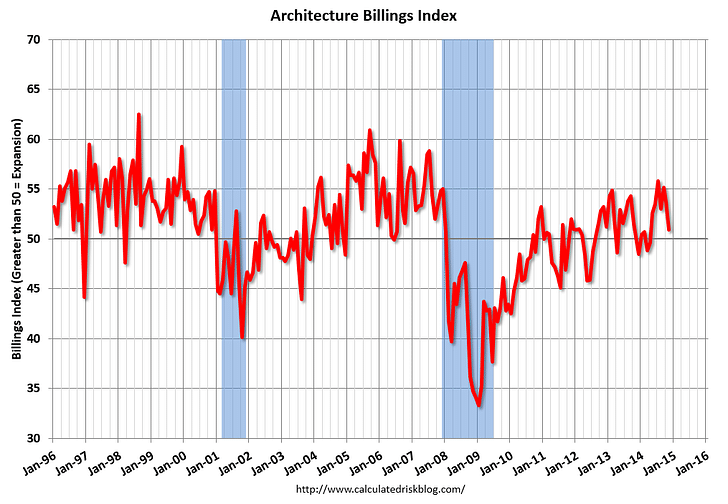

The AIA’s Architecture Billings Index reflects Baker’s assessment. During the pandemic, billings by architectural firms saw less than one year of consecutive monthly declines (March 2020 to January 2021), before seeing consistent growth every month to the present day (July 2022). For comparison, the 2008 economic crash saw billings decline every month for two and a half years, from January 2008 to July 2010, with a sustained period of growth only beginning midway through 2012.

The dichotomy, though stark, is not unsurprising when considering the contexts of both crises. As Baker notes, the 2020 recession was triggered by the ‘flicking of a switch’ to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and had little to do with how the U.S. economy, or sectors applicable to the architecture profession, were performing. The 2008 recession, meanwhile, was set in motion by a collapse in the real estate market; an intrinsic flaw in U.S. economic practices with the architectural profession near its epicentre.

Firms were complaining about their ability to attract quality talent even before the pandemic. It is a very serious problem that looks to be getting worse.

Baker remains largely positive about how the demand for architectural services fared through the past two years. His chief concern, however, centers on the operational challenges facing architecture firms; predominantly an ongoing shortage of architectural staff.

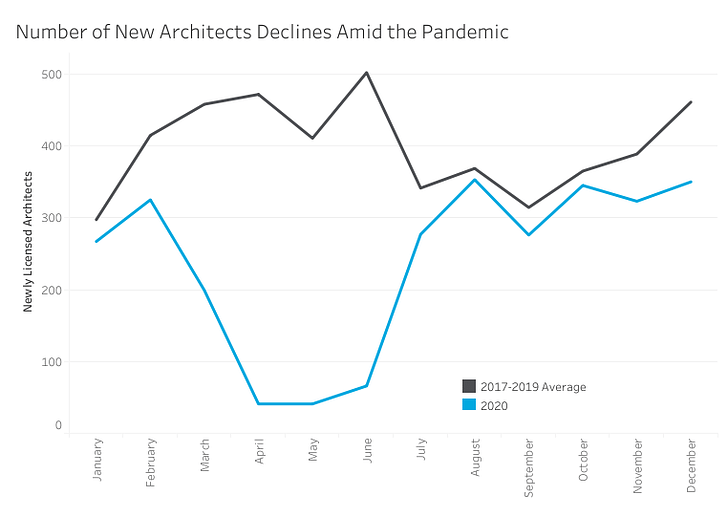

“Over the past year or 18 months when we talk to architecture firms, their number one concern is staff retention and recruitment,” Baker told us. “It has gotten worse over time rather than better; there is a lot of demand [for staff] and not much supply.” According to NCARB, the number of licensed architects in the U.S. rose by 5% in 2020, before declining modestly by 0.3% in 2021, caused predominantly by fewer-than-typical newly licensed architects entering the field. While the past decade has seen consistent growth in U.S. architect numbers by an average of 1.7% per year, NCARB warned in their 2021 annual review that the impact of the pandemic on licensing may take years to resolve.

“It’s not that we have lost a lot of people from the profession during the pandemic,” Baker explained. “Firms were complaining about their ability to attract quality talent even before the pandemic. It is a very serious problem that looks to be getting worse. With the non-residential market now coming back, we expect to see healthy growth in construction activity for the next 12 to 18 months, but not much of an increase in staffing.”

Curious about the root cause of this surge in unfilled job opportunities, which Archinect has also observed on our jobs board, we asked Baker if the so-called Great Resignation was responsible for the supply-demand imbalance. At first glance, well-documented issues in architectural labor conditions align with those fuelling the Great Resignation, including low pay, a lack of opportunities for advancement, and a feeling of disrespect at dispensability in the workplace. However, Baker is not convinced.

“If you devoted the time, energy, and financial resources to becoming an architect, you’re not likely to say ‘I’ll move on and try something new’ as some may in other industries,” Baker told us. “Architects have certainly been looking seriously at other firms whose structure more closely aligns with their priorities. I wouldn’t call that the ‘Great Resignation’ because implicit in that phrase is the idea of looking for a new career path. I haven’t seen evidence this has impacted the industry. I think it is more a case of architects carefully curating what firms they will entertain job offers from by analyzing both their own career path and firm’s approach to projects and social consciousness.”

The supply and demand of architectural labor is almost never in harmony.

For Baker, misalignments between the supply and demand of architectural labor versus industry needs is less about short-term crises such as pandemics or financial collapses, and more about a fundamental mismatch between the qualification system that produces architects, and the economic system that sustains them.

“In architecture, we have a chronic problem,” Baker explained. “There is a fairly fixed pipeline of candidates to fill positions; normally graduates of accredited architecture programs. Our system steadily produces approximately 6,500 such graduates per year. However, construction is an extremely cyclical sector of the economy, one of the most cyclical. Having a 10% increase or decline in construction spending on the previous year is not at all uncommon. But increasing or decreasing architectural staff by 10% per year is a dramatic move for firms. It is not like the food service industry, for example, where you can attract workers from other industries and rapidly facilitate training.”

While Baker concedes that abnormally turbulent conditions such as the COVID pandemic can exacerbate this mismatch, AIA studies of the issue have found that the supply and demand of architectural labor is almost never in harmony.

“If you look at the volume of construction activity as the definition of what the need is, and the number of architectural staff at architecture firms as the supply, those are almost never in balance,” Baker explained. “They flow between being oversupplied with staff and being undersupplied. There are rare periods of a month or two where the lines cross and are in sync. It’s a chronic issue, and there isn’t a silver bullet answer.”

Curious about how Baker’s national analysis manifested in the field, we reached out to firms to hear about their lived experience of the past two years. We began in New York City with Fogarty Finger founder and director Chris Fogarty.

In early 2020, with COVID-19 moving from China towards Europe, Fogarty’s firm could read the writing on the wall. “We knew it would inevitably impact the United States too, so we mobilized our ability to work remote very rapidly.” Fogarty told us. “We took the attitude that staff could relocate to anywhere they wanted, as long as they could adhere to our time zone.” The unpredictability of the pandemic’s early months brought a halt to the firm’s design-stage corporate and office work; a hole filled in-part by PPP loans and the timely payment of invoices by clients.

Fogarty also attributes the firm’s resilience to its ongoing construction work. “Our projects can take anywhere from six months to four years on-site,” he explained. “Construction projects already underway were reliable, as were their fees. Our main worry was where to source new commissions. But as 2020 progressed, investor confidence rallied. Interest rates were virtually zero, so if you were a client, there was never a better time to build. Bit by bit, our clients emerged with new commissions, particularly in multifamily projects. By September 2020, our resurgence was underway.”

Perhaps we are still on one side of the pendulum at the moment, but as the economy changes, we will perhaps swing a bit closer to the middle

Today, with the emotion, fear, and worry of the pandemic in the rear-view mirror, Fogarty’s attention has now turned to the challenge of balancing remote and office-based working. At present, Fogarty Finger’s New York City office operates a hybrid pattern, with 50% of staff in the office at any one time. “We are a big firm of 130 people so communication is difficult,” Fogarty conceded. “We are still trying to make communication as seamless as it was before the pandemic.” The resilience demonstrated by Fogarty’s staff throughout the pandemic has renewed his trust in their ability to perform their roles outside the office, leaving him openminded about the future of his physical workplace. However, he remains concerned over the impacts of remote work on mentoring junior staff, who rely more on being immersed in the physical workplace for direction, and for growing their knowledge of the profession in practice. “I think there are lasting shifts that have happened,” Fogarty surmized. “Perhaps we are still on one side of the pendulum at the moment, but as the economy changes, we will perhaps swing a bit closer to the middle.”

Beyond balancing hybrid work schedules, Fogarty is also experiencing the same recruitment challenges highlighted by Baker. “There’s a terrible shortage,” Fogarty told us. “It’s our single biggest problem.” Echoing Baker’s scepticism, Fogarty did not see the Great Resignation manifest at his firm. However, the shift to remote working saw many of his staff leave New York City, particularly colleagues with young families and a newfound ability to move to more spacious homes in less dense communities. “Over two years, we have churned through 30% of our staff, which is 10% more than we would expect,” Fogarty estimated. “We saw some colleagues move to other parts of the country such as Texas and Miami, who in time, have decided to remain there permanently and move to architecture firms in their locale.”

The change hasn’t been entirely negative, however. The freedom of remote working saw one of Fogarty Finger’s directors move to Atlanta, resulting in the firm building a satellite office of ten people in the city. A similar situation also saw the firm set up a Boston office; a diversification which Fogarty believes would not have happened but for the pandemic.

In discussing the firm’s recruitment needs, Fogarty cites a particular shortage of job-seeking architects in the 7-10 years’ experience range. “If they are good, no firm will let them go,” Fogarty explained. “You are therefore trying to catch people in a particular circumstance, such as moving city or deeply dissatisfied with their current job. It’s a very small pool of people, and you are competing with many firms to hire the best of the best.”

We aren’t even competing against other architecture firms; we are competing against the fact that more and more people don’t want to be an architect.

Fogarty cites many reasons for this shortage in job seekers; a shortage which, for him, pre-dates the pandemic. He cites the 2008 financial crisis as a seismic event that created a ‘missing generation’ of architects who, had they continued in the industry, would now occupy the 7-10 years’ experience role. “The 7-10 year experienced individual can also be the same person who is entering a time of their life where they are thinking about starting a family,” Fogarty added. “New York City can be a tough, expensive place to grow a family.”

Fogarty places the heaviest blame for industry recruitment challenges on the profession itself, however. “We aren’t even competing against other architecture firms; we are competing against the fact that more and more people don’t want to be an architect,” Fogarty explained. “In some ways, why would you? You can work for Google and get paid five times as much for your starting salary. The issue is not better or worse because of any single event or mechanism. The profession just isn’t enticing enough to enter in the first place. You have to find people who love architecture with a deep passion.”

In the face of these challenges, Fogarty Finger has employed several approaches to recruitment. "We try to grow our own colleagues,” Fogarty explained. “We start with internships, allow the individual to grow, and hope nobody else takes them!” The firm has also formed connections with ten schools around the U.S. and financially supports colleagues who return to their alma mater for career fairs. Other initiatives described by Fogarty include an accelerated shift towards BIM and 3D rendering to match the software preferences of young candidates, and the hosting of social events to maintain positive energy levels across the practice.

I don’t think the profession is set up the right way.

While taking proactive steps to address recruitment challenges, Fogarty is conscious of those intrinsic supply-demand imbalances outlined earlier by Baker, and believes the most effective solutions are largely out of his hands. “I don’t think the profession is set up the right way,” Fogarty told us. “We should be encouraging the growth of technicians who, unlike architects, can train for two or three years and perform auxiliary roles similar to how nurses and assistants work with doctors. This would improve diversity in the workforce, but also allow people to become licensed through an apprenticeship model.”

“When you go to a dentist, it is a dental hygienist who cleans your teeth, not a dentist,” Fogarty continued. “Only in architecture do we think that a licensed architect needs to draft toilet elevations. It is a poor use of our time and, until we figure out a better way of managing our profession, we are always going to be at the beck and call of the economy. It’s completely wrong, but it is higher up than me. It’s the education system.”

In downtown Los Angeles, 2,500 miles away from Fogarty Finger’s New York office, AUX Architecture founder and director Brian Wickersham recalls the beginning of the pandemic vividly. “I remember bringing the entire office together on March 13th 2020 to talk about what we were going to do about this global pandemic; a talk I thought I would never have to give in my life,” Wickersham recalled. “I told my staff that I started this company in 2008, during one of the toughest times I can ever imagine for our industry. I told them that we got through that crisis, and that we were going to get through this crisis together.”

By all accounts, Wickersham delivered on his word. Throughout the pandemic, AUX’s staff count grew by 30%, now sitting at 32 people. The firm’s workload, which is dominated by residential projects, also remained resilient, giving credence to Baker’s earlier assessment that residential-led firms exerted a stronger performance during the pandemic. In addition to a large influx of multifamily and low income housing projects through 2020, AUX also saw some commercial projects repositioning as residential schemes. The only project of AUX’s to stop during the pandemic was a hospitality commission, which as Wickersham explains, was reignited through an investment by the firm itself.

“A couple of months into the delay, we approached the client and proposed an overhaul of the project in which we offered to become one of the anchor tenant,” Wickersham told us. “We redesigned the building, took over one third for our new office, reduced the square footage of a proposed restaurant to occupy another third, and brought an art gallery on board to occupy the final portion.” Wickersham sees the result as a sort of ‘creative compound’ in the heart of Los Angeles from which his colleagues can draw inspiration. “We’re not just using synergies in our own work, but also get to experience the culinary creativity of the restaurant, as well as the gallery’s fine arts, paintings, and photographers,” Wickersham explaind. “This has always been a foundational focus of ours: the creative arts.”

You can teach software, procedures, and much more. You cannot teach a person to share your core values.

For Wickersham, AUX’s resilience throughout the pandemic isn’t solely the result of their residential portfolio, and is instead a testament to their longstanding approach to recruitment. “From the pandemic, we have seen that we succeed best as a firm when we look for people who share our core values as a company,” Wickersham told us. “It is a simple recipe, but one which can easily be forgotten during the mayhem of a pandemic. As we transition back to a normal studio environment, we are once again returning to our focus on collaboration, and the core values that made us succeed both as designers and as a studio.”

In a recruitment market that often measures candidates by experience, be it years, sectors, or skills, Wickersham takes a different route. “We are looking for people that align with our core values; communication skills, creativity, and tenacity,” he explained. “The rest is on us. You can teach software, procedures, and much more. You cannot teach a person to share your core values.” By de-emphasizing experience in favor of values, however, Wickersham stresses the importance of establishing systems that can train recruits, teach them appropriate systems, and integrate them into existing teams.

Like Fogarty Finger, AUX never saw any manifestation of the Great Resignation across their office, though Wickersham notes that staffing shortfalls in adjacent industries, such as contractors and suppliers, means the firm must place a heightened effort on ensuring project timelines are maintained. Of the few people who did leave the firm during the pandemic, Wickersham observes that each departure was by someone who had joined the firm during the pandemic, and that onboarding and retaining staff was one of his heaviest challenges over the past two years.

“Before the pandemic, we had one person quit in three years,” Wickersham told us. “We have a good work environment, and we work hard to make sure we maintain an environment that people want to be in. Unfortunately, those who joined during the pandemic never got to experience that environment in person.”

In response, AUX implemented a series of steps to help new recruits assimilate into the practice. “We worked hard to make sure people saw our culture and felt invested in it,” Wickersham explained. “We implemented buddy systems, took more time to reach out to people personally, and took people to lunch when pandemic rules allowed.” A key lesson from the pandemic, which AUX plans to continue in the future, was ensuring that new recruits were not placed on new projects immediately after being hired.

“We realized new recruits were coming into a new system they didn’t understand, and were given a blank piece of paper with limited interaction from other leaders,” Wickersham told us. “We therefore started integrating new recruits into teams that were running projects at more advanced stages, which was hugely successful. You could see a set of drawings, understand how the team works, and immerse in the dynamics of how we work and communicate as an office.”

Our work is our billboard, so taking pride in it is the best thing we can do to recruit.

One point of departure during the pandemic between AUX and the wider profession was AUX’s perceived lack of difficulty in recruiting. Wickersham reports that, aside from a period of uncertainty in the middle of the pandemic, any open positions advertised by the firm were met with high response levels.

“I think it is because we bring people into the office,” Wickersham told us when asked to share his secret to success. “Applicants can see the work around them, which is exciting. We have also secured some dynamic commissions in the past few months, which excites candidates. A big part of my approach to recruiting is making sure our work is compelling. Our work is our billboard, so taking pride in it is the best thing we can do to recruit. You are asking people to invest a lot of themselves in these projects, to care about what they are doing. We make our recruiting about the things we care about, so that we attract likeminded people. Maintaining truth in who we are is really important.”

Like Fogarty Finger, AUX has transitioned back into a hybrid office structure, with people working from the office two or three times per week. Wickersham is confident in the firm’s ability to make a hybrid pattern work, though echoes Fogarty’s mixed feelings on digital communication tools. “I feel like I’ve done more interviews in the last two years than at any stage in my career,” Wickersham told us. “It is difficult to conduct interviews over Zoom, to get a sense of who a person is. A return to in-person interviews has been welcomed.” However, Wickersham also recognizes that the digital medium has also enabled the firm to recruit people from further afield, including the East coast and Europe; something that the firm plans on maintaining.

Looking to the future, ‘diversity’ is the operable word in AUX’s business and recruitment plans. “Residential work carried us through the pandemic, but these things are cyclical,” Wickerhsam told us. “Now we must look to diverse markets and sectors, which also filters into recruiting. The more diverse the voices are in your studio, the better your work will be. When you start a small firm, so much of the firm’s personality comes from your own personality. What drives me is being around a diverse group of people, hearing different perspectives on the world, and learning from different people. We will always be focused on that.”

Beyond the metropolises of New York City and Los Angeles, the impact of the pandemic on the architectural profession was no less destabilizing. For Multistudio, formerly Gould Evans, a practice of 150 people with five offices across Kansas City MO, Lawrence KS, Phoenix AZ, New Orleans LA, and San Francisco CA, the onset of the pandemic brought rapid changes to the firm’s operations, project focus, and recruitment strategy.

“March 2020 seems like a lifetime ago, and it can be easy to forget how uncertain everything felt for the industry,” recalled Heather Gentili, Multistudio’s Director of Human Resources. Like many firms, pandemic restrictions forced Multistudio to close their offices and revert to remote working. But unlike many, this shift was not entirely alien. “Prior to the pandemic, we actually had a decent handful of remote employees,” Gentili told us. “Our remote employees sit in locations where we do not have studios, and when combined, equate in number to an extra studio for the firm. We had already embraced the idea that talent can come from anywhere with the right tools and right support.” Their prior experience in remote working meant that Multistudio had transitioned fully to a remote setup before government orders would have mandated it.

Two years later, Multistudio’s project pipeline is returning to pre-pandemic trends. Gentili reports a return of large projects that stalled amid the pandemic’s economic uncertainty; a disruption which saw small, boutique projects take a larger than usual portion of the firm’s revenue. “Our main focus now is figuring out how to effectively implement hybrid working,” Gentili noted, echoing earlier sentiments from Fogarty and Wickersham. “I believe our firm will continue to support a hybrid approach, but we are still exploring how we can manage it most effectively, and where there are weak spots.”

Gentili also shares our other interviewees’ scepticism over the impact of the Great Resignation on the profession. While noting that Multistudio is 15 to 20 staff shorter after the pandemic, Gentili has not been alarmed by the trend. “When someone moved on during the pandemic, we took it as an opportunity to rightsize our mix of staff, so therefore were not as quick to backfill the vacant position,” Gentili explained. “In other industries, the Great Resignation was fuelled by a misalignment of values between the individual and organization, but for architects, those values were still woven into what they want to accomplish through their architecture, and the impact their work can have on a community.”

Of those who did leave the firm, Gentili adds that most held under a decade of experience, a group which also saw higher churn rates before the pandemic. “That entry-to-mid-level cohort should be exploring different work environments and studio focuses in order to fully uncover their passions,” Gentili explained. “Multistudio is a deeply multidisciplinary, multisector, multistate operation, and many of the people who moved on did so to firms who are more niche and focused, which is to be expected in some cases.”

We wanted to ensure that the talent pool we were pulling from was an accurate representation of the communities we were serving with our architecture.

With their project pipeline returning to pre-pandemic levels, Multistudio have stepped up their recruitment effort in recent months. Similar to Fogarty’s analsysis, Gentili reports difficulty in hiring the right candidates; a difficulty which predated the pandemic. “It’s not that there isn’t the talent or skill out there,” Gentili told us. “Many firms are looking for greater talent, so inevitably it creates strong competition to attract candidates. The advent of remote working has at-least meant that we aren’t confined to zip codes near our office, meaning we can cast a wider net in the search for new colleagues.”

While the pandemic placed a temporary hold on recruitment at Multistudio, the firm used the pause to investigate how their hiring process could be used in the future to improve diversity at the firm; a process which was already underway before the pandemic hit. “In early 2020, we were working with our internal equity groups to understand how our recruiting was prohibiting the increase in representation of Black architects and designers, and to understand any unconscious bias we had,” Gentili explained. “We wanted to ensure that the talent pool we were pulling from was an accurate representation of the communities we were serving with our architecture.”

The intentional push to improve diversity led to a change in Multistudio’s recruitment process. Where the firm once relied on recruiting based on referrals, this approach has since been expanded to include relationships with colleges and architecture schools, with an emphasis on HBCUs. In addition to growing the firm’s racial and ethnic diversity, Gentili sees the approach of engaging with students early in their career as crucial to empowering women. “We believe that too many women are leaving the profession after five to ten years, so we want to use early engagement to address that,” Gentili told us. “We also conduct ‘blind reviews’ of candidates, where we take away any factors that may trigger an unconscious bias such as name or location. We focus instead on the portfolio of work, and ask if it aligns with our own.”

“Architecture, and the wider design team, can benefit greatly from diversity,” Gentili continued. “We look for design ability in our recruitment process, but we also look for people who understand the impact of design on the health and wellbeing of users. If we can take anything from the pandemic, it is the importance of challenging ourselves to reflect on our mix of staff, and how it helps us achieve this mission.”

Though our conversations spanned three firms, in three regions, with three differing contexts and nuances in their pandemic journey, they raise similar questions about the resiliency of contemporary practice. While the COVID-19 pandemic represented a turbulent, disruptive, and unsettling moment across the profession, its reverberations across the industry appear dampened when stacked against those of the 2008 financial crisis. We can feel relieved that this economic pain was relatively short-lived, but relief cannot give way to complacency. The next economic crisis, when it inevitably arrives, may not be so short-lived.

All of our conversations for this piece, in their own way, expose the same two challenges inherent in the industry. First is the ever-fluctuating misalignment between the supply of architectural labor, and the demand for architectural services: fluctuations which confronted all three firms we spoke to and, according to the AIA’s Kermit Baker, a majority of firms across the country.

There is greater room for the use of auxiliary professionals in the office.

While Baker concedes there is no ‘silver bullet’ to rectify this imbalance, he did offer us a variety of possible solutions, pointing to reforms in how firms are structured and operated. “There is greater room for the use of auxiliary professionals in the office,” Baker told us. Echoing Fogarty’s early analogy, Baker compares the structure of an architectural practice to that of a dental practice, which may comprise many employees, only one of whom is a licensed dentist. “The ratio at architecture firms is very different,” Baker continued. “About 60% of employees at architecture firms are architects, or graduates pursuing a license. Architects therefore often perform tasks that a colleague with one year of BIM training could perform, instead of more specialized roles that reflect their long education. Firms should ask how they could leverage their current architectural staff more efficiently, and fluctuate their use of auxiliary professionals to avoid laying off core staff in recessionary times which may be needed again during prosperity.” Baker also suggests firms examine their use of technology as a means of boosting workforce productivity, and dampening the fluctuations in staffing shortages and surpluses.

A sudden spike in the demand for architectural labor, as experienced by many firms through 2021 and 2022, highlights a second challenge for many firms including those we spoke to: how to attract job-seekers who share a firm’s ethos, and are more likely to become long-term, valued colleagues, at a time where such applicants are in short supply and high demand.

Ultimately, businesses are going to have to factor what their workforce is looking for.

All three firms we spoke to shared their unique approaches, from Fogarty Finger’s leveraging of architecture school connections, to AUX’s expression of company culture, to Multistudio’s emphasis on diversity. For Baker, firms across the country will likely be required to develop an expanding list of such incentives to stand out in a competitive market which, in his view, will continue into 2023.

“Company culture should be high on any firm’s list,” Baker told us. “Firms need to create an environment where staff feel comfortable, motivated, and have input on decisions that the firm makes. Applicants are also becoming more particular about what kind of projects they will be working on, what the social impact of these projects will be, what their potential for advancement is, and how their new role might enable them to develop their skills.”

However, by Baker’s assessment, architecture firms in their current business model are unlikely to be in a financial position to address the compensation disparities between architecture and other industries as expressed by Fogarty. “Firms have seen an inflation in the cost of doing businesses, but their ability bring in revenue hasn’t matched this increase,” Baker explained. “They are therefore in a bind where they cannot generate revenue fast enough to keep pace with higher business costs, or to ramp up financial incentives for new recruits. Because firms cannot afford to get into bidding wars with each other for hiring, they are going to have to pay more attention to other incentives, such as workplace culture.”

“Today, much of the leverage and bargaining power is on the side of the employees,” Baker concluded. “Ultimately, businesses are going to have to factor what their workforce is looking for.” Such advice carries significantly more weight in the post-pandemic professional landscape; where workers are increasingly recognizing the power they hold, and how they can collectively wield it in the name of better working conditions.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

4 Comments

There may be other element(s) that has not been taken into account. First, most architecture programs do not fully prepare students for working in a real studio environment (i.e. training on proper construction documentation). Second, there are some firms that are reluctant to provide proper training to inexperienced designers. It's understandable that it is a time issue when compared with working with clients and consultants on a regular basis, which may be a reason to which proper training is lacking. Bottom line, schools can do better and so can architecture firms. Why? Because having a "sink or swim" mentality can unintentionally discourage people from becoming architects.

Why is it so complicated? Money. Pay people a living wage and they will work. Licensed architect with 7-10 years of experience here. The so called unicorn. I do NOT work in an architecture firm. Why? I would like to not be homeless. What a concept. Increase your fees. Learn to use excel. Stop holding up your nose to anything and everything under the umbrella of architecture that isn’t pretty rendering ‘design’. Take back the responsibilities that were given away to other niche professions - eg project management. Stop wasting time doing 50 design iterations no client asked for. Manage client expectations, if they request something extra, charge for it. They will pay. If it takes more time, say so. Grow a spine. Consider your time and your staffs time to be of value. Stop thinking the field is ‘art’ or ‘passion’. Dollars. Hire actual financial experts to run the financials instead of art school architects who drive the business into the ground. Hold sub consultants accountable to their contracts. Don’t treat your entry level staff like they’re dispensable, clearly they aren’t. Manage time. Manage money. Stop doodling and dilly dallying. The brain drain will continue so long as the field expects people to be clever enough to perform the responsibilities required of a licensed professional while somehow being stupid enough to be paid less than a union janitor.

Does this ideal AIA employee exist?

The criteria: shares values of firm, 6-7 years of school (indebted) + long license process (wealthy family) + proper representational identity (usually not wealthy) + naive/idealistic enough to overlook the extreme professional corruption, broken design process, decreased salaries, etc.

We aren’t even competing against other architecture firms; we are competing against the fact that more and more people don’t want to be an architect.

When will the arch profession actually do something about the problem? Deregulate the profession and start advocating for ARCHITECTURE not rent seeking institutions. Then the value of the profession will increase. Instead the arch elite bureaucracy just wants to diversify to trap more people in a rotten system.

Why are there so few people sitting around in bottom tier positions in offices for 7+ years? Because we can't afford to! I have friends who make more as teachers with 3/4 year pay making the same as we do in architecture for the same amount of years, with less financial obstacles in the way (education, licensing, etc). If our industry is supposed to be have this profound impact in the world in "protecting the life safety and welfare" of every person that enters the building, our pay should reflect that on every level not just the highest level of staff. I went through my whole career and fought with every ounce of strength I had left to earn my license only to find there is little to no compensation value to it. I spent more in study material and fees than what the pay scale reflects. I have worked in big cities and small cities and no one pays what the AIA guidelines suggests. At this point I'm looking at work on the construction side or other alternate design routes to make up years worth of missed income in the pursuit. Its not for lack of passion. Its for lack of respect.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.