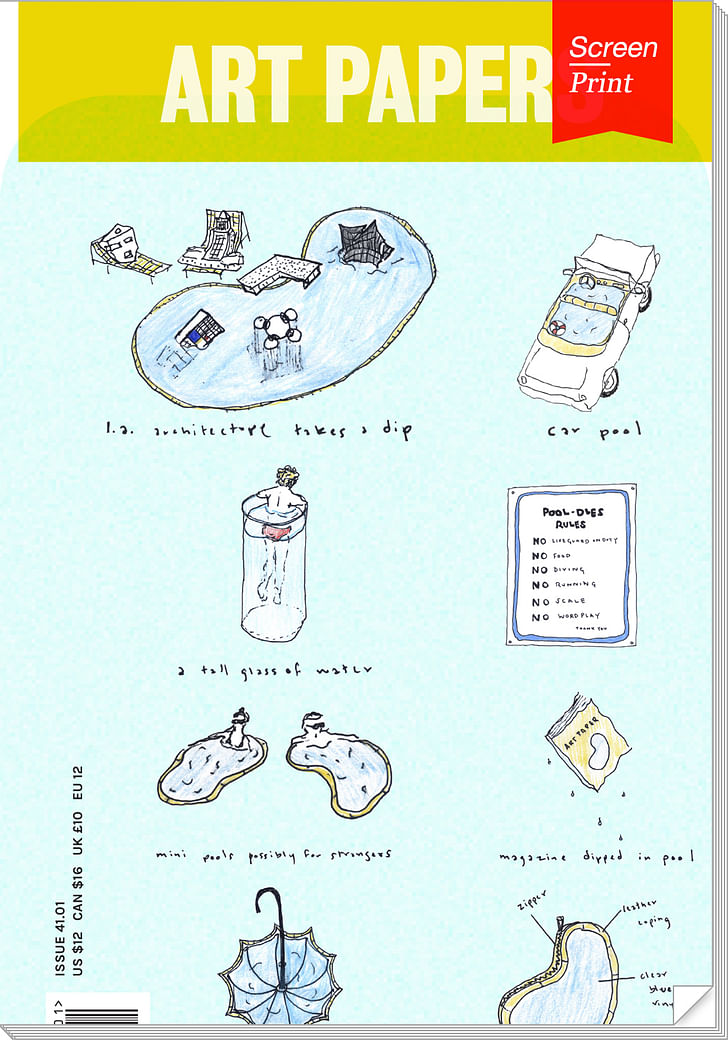

"Film, case study houses, rooftop parties, rec centers, hotel lobbies, and other watery spaces such as car washes, reservoirs and the LA river" are just a few of the "LA knowns" that the pool conjures up for Jennifer Bonner, a guest editor for the latest issue of Art Papers.

And what is a more iconic symbol of summer in Southern California than the pool? Whether in a backyard or a hotel rooftop, the pool's bright symbolism has become a strong cultural marker for the city of Los Angeles. As Katya Tylevich puts it, "that bright, blue puddle of chlorine—the yearlong swimming pool—is one of Los Angeles' ubiquitous symbols of positivity, of beauty, excess, and enhanced real estate value."

For our latest installment of Screen/Print, we are featuring an excerpt from Art Papers, an independent publication based in Atlanta covering contemporary art and culture. Their current issue, guest designed by April Greiman, is specially focused on architecture and design and explores the Southland through it's distinguished water-type, the Pool. We have selected an essay from the aforementioned LA-based writer in which she takes us through her 18-mile journey, charting LA's aquatic geography.

A forward crawl

by Katya Tylevich

In John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer” (1964), the title character swims eight miles from a cocktail party to his large suburban home by using the pools carved across his wealthy neighborhood. The man makes his initial dive with the confidence and vigor of a middle-aged 1960s WASP, secure in his status. By his final exit from the waters, however, he is physically and spiritually injured, whacked by past mistakes and assumptions, and knocked from his position in society. Each leg of his journey—that is, each pool—brings into focus an episode from his life and the consequences of past arrogance. In 1968, the story was adapted for a film of the same title by Eleanor and Frank Perry, with hunky Burt Lancaster in the starring role, and bearing poetic relevance to America’s hostile politics and society at the time.

Imagining a disaster is easier than preparing for one. A swarm of small earthquakes around the San Andreas Fault has triggered an earthquake advisory. We are in year five of a severe drought, and, at present, Los Angeles is being singed by unseasonable heat. Who watched those terrifying presidential debates the other night? Read the news this morning? Poured a drink and picked a fight? And these are just our collective disasters, to say nothing of the private. The brain’s neurotransmitters have abandoned post. Here we are in late autumn, unhinged, even for us.

Though we could use some rain, it’s actually dark clouds of probability that hang over Los Angeles. I move from the city’s west to its east, traveling across public (or, at least, accessible) bodies of water, mapping out an exit strategy for when the roads buckle, break, or jam. Flying over this city in an airplane, one sees a pool in every fenced backyard (visions of water going unused). Don’t try doing laps across private property uninvited, though: armed patrol is in force. Chihuahuas are trained to attack.

Here, people move about their daily business, ignoring big banners advertising survival kits. Buying one of those is just an invitation for bad luck. Better to be optimistic. That bright, blue puddle of chlorine—the yearlong swimming pool—is one of Los Angeles’ ubiquitous symbols of positivity, of beauty, excess, and enhanced real estate value. The pricier the neighborhood, the bigger the swimming area. I have to search a little harder for pools that don’t require a formal invitation for attendance.

The westernmost point of this expedition could pass for America’s Midwest, possibly its Northeast. A canopy of leafy trees provides shade on a day when it is very much needed. Doesn’t look like the desert here, but, anyway, no water in sight or on site. The city pool at the Rustic Canyon Rec Center in this upscale corner of LA’s Westside has been emptied for the season. Deciduous leaves line the blue crater.

A solitary adult woman of indeterminate age and her senior Yorkshire terrier, neither pleased by the presence of an unfamiliar human soul. My eyes avoid theirs, bending instead toward what looks like a Ray Kappe home beyond the locked chainlink fence surrounding the pool, beyond the sign barring those with “active diarrhea” from the waters, another sign, warning, “$500 fine or 6 months in jail or both for entering pool or premises when closed.” Steep sentence, all things considered.

Kappe is a revered architect in Los Angeles, celebrated in particular for the modern glass and redwood single-family homes he built in the 1960s and 70s around this area, tucked into a canyon just west of postcard LA. These homes come on the market every so often, and sell for prestigious sums to people willing to care for landmarks, integrated with nature to the point of camouflage.

In Los Angeles, privacy is valued over ocean view, maybe because the Pacific is littered with rejected items and humans. In its proximity to people, the ocean brings with it two threats: being seen and having to see.

The ocean water is cold. The heated pools that run parallel to it belong to private hotels—fortressed by design, by manicured hedges, by hotel security, and separated from the beach by a busy street. Across that street, on the very edge of the sand, the Annenberg Community Beach House is hosting its final outdoor pool day of the summer season. Moms, for whom the words “juice” and “yoga” are verbs, compete for a cut of chlorinated water on behalf of their children.

The Beach House, in Santa Monica, is north of the DMZ separating it from Venice. Splashing youths at the Beach House are barely aware of the Venice drum circle, the vape smoke pluming above bongos, the tent cities in the alleyways of luxury condos, and the satisfied detectives, drinking coffee and shaking hands after their 3 a.m. standoff with a hopped-up burglar, whom they took into custody alive.

Like many of the buildings in LA, the Beach House has its roots in the 1920s Golden Age, when newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst developed the property for his lover, actress Marion Davies. Our own private Hearst Castle by the sea. It later became a private club, and then was converted for public use in 2009 with the backing of philanthropist Wallis Annenberg and the architecture of Frederick Fisher & Partners, who crafted something modern, geometric, and sustainable, in a neighborhood characterized by single-family bungalows. This pool is popular, it’s civic, it has no room left.

Eastward: private homes and apartment buildings, with heated year-round swimming as a selling point. Until a turn north, through Beverly Hills, where baroque gates secure (presumably) saltwater pools from intruders.

Manifest Destiny through the hills to Coldwater Canyon Park, where paparazzi have photographed Mark Wahlberg and Heidi Klum supervising their respective children splashing in the park’s small, shallow manmade stream.

No celebrities today. Civilians holding to-go salads provide a canopy of leafy greens (kale, Swiss chard) for this manicured grassy plot hit by direct sunlight. A view of the mountains, a McMansion, an orange grove—pretty Southern California stuff, not at all private, though. It’s busy on the weekends. I wonder if celebrities take their children here mainly to socialize them.

A sign near the small brook warns photographers that a permit and fee are required if they are to turn a profit from their day at the park. The children wading in the water today are not financially viable. They’re boring to look at. All they represent is the natural propagation of life, which is perhaps more than can be said of the manmade stream, which I assume is 99% disinfected of pathogens. Beware the 1%.

But Los Angeles is an urban metropolis, and the city calls. Traffic, push me down your side streets, pull me east between the strip-malls and the mid-rise boxes. Not only is it an election year, but an Olympic year. Where better to deposit excess patriotism than in an Olympic pool?

The outdoor Uytengsu Aquatics Center, known formerly as McDonald’s Olympic Swim Stadium (aka born again at the Golden Arches) was originally built for the 1984 Olympics at the University of Southern California Campus. It’s a big, beautiful pool, in which the water never turns green, in which the world’s preeminent synchronized swimmers and divers have been baptized.

I can’t get in. I can’t even try the door (which is locked, anyway). I can’t find a place to park. There’s a football game at the adjoining stadium. Scalpers stand along the street for blocks, slinging not tickets for the game, but parking spots … for $30, $40. A city where vehicle storage is more coveted than experience. I keep driving.

Twenty minutes later, downtown, I find valet parking for just $15 dollars, thank you very much. Torn between the indoor pool at the Biltmore Hotel (Roman bath meets art deco) and the rooftop party waters at The Standard hotel, I choose the road most traveled.

In the elevator, on the way up, I practice gratitude for arriving on a night when access to The Standard pool is not reserved for a private party. The elevator doors open to a panoramic view of Los Angeles. In the twilight, perched on a quintessential LA site, I survey its idiosyncrasies. The pool, empty on a slow night, reflects the city’s lights. I think that tomorrow, I’ll portage over the mountains and to the Valley to the Hansen Dam Aquatic Center, where I will see both a lake and a pool. I hear that there are two waterslides there, and strict security, and free parking.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured an excerpt from Art Papers.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

1 Comment

Dig it!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.