According to research from 2015, between 35-38% of people do some, if not all, work from home. And, even back in 2009, a study found that 1 in 5 spent two to ten hours working from bed. In short, the way we work and live is changing, as many ditch (or have to ditch) the commuter express for their bedrooms. While Walter Benjamin said of the 19th century, “for the private citizen, for the first time the living-space became distinguished from the place of work,” in the 21st, that distinction is blurring once more. Alongside this, the split between the urban, as loci of labor, and the rural or suburban, as retreat, is complicated.

Inspired by these shifting and recursive dynamics, Ways of Life is an “investigation into the new condition of working in close proximity to nature.” Curated by Christoph Hesse and Neeraj Bhatia, the project comprises a series of commissions for prototype dwellings that bring work into nature and clarify relationships between labor and leisure, the individual and the collective. Each of the nineteen invited emerging practices developed designs that will be first exhibited at EXPERIMENTA URBANA, a co-event of documenta14 in Kassel, Germany and then later realized.

“Away from the city, dwelling in nature is not only a key symbolic gesture of escape, it has collapsed urban labor in close proximity with the wilderness,” they write. “This new domestic space type is significant because of this spatial collapse, as our relationship with work, family, and nature needs to be negotiated through architecture.”

Away from the city, dwelling in nature is not only a key symbolic gesture of escape, it has collapsed urban labor in close proximity with the wilderness

Sited on the Kellerwald-Edersee Nature Park, a bucolic lake-adjacent area fifty kilometers away from Kassel, the nearest city, the project was instigated by a developer who wanted to build houses and a mayor who proposed erecting a small residential estate instead. “There was always discussion about how to create density in these geographies that are quite pristine,” Bhatia tells me. “What is the right amount of density? What is the right type architecture? What's at stake with the design?”

Bhatia notes that projects in these types of geographies rarely involve architects, particularly more experimental ones. When choosing who they involved, Hesse and Bhatia looked for architects that they respect and whose work “somehow questioned ways of living or domestic space or an engagement with the natural environment,” Bhatia states.

Here’s a look at each of the projects:

It is a house that sits lightly on the earth, both in terms of ecological and actual footprint. A house that demands from it’s inhabitants to follow the circle of seasons. As only half of the space is closed, there is a time for reflection and preparation (winter, spring) and a time for action and implementation (summer, autumn). Made from materials of the surrounding, the house uses and crafts the local potential as well as plays with the building tradition. The order and elements of a traditional timber-frame-structure are cited but a bit “offbeat” and assembled in a new way.

the house uses and crafts the local potential as well as plays with the building tradition

The building process is just as important. As Maslow states in his Hierarchy Of Needs self-actualization as a very important element of human nature, we believe that the possibility of self-building adds to an intensified living quality. In addition to that it creates work opportunities and know-how. This is why we could also imagine this building being constructed during a Design–Build workshop. The techniques chosen are low-tech and require lots of hands: a good scenario to include architecture students as well as refugees. Particularly for earthen structures there aren’t many hands-on learning possibilities.

The ground floor is an open, shaded space that can act as a workshop for dirty works. If needed it can be closed with a very basic rolling shutter. The top floor is a living area for two persons. A furniture block in the middle contains all the essentials units like kitchen, bathroom, beds and working tables. In order to get more autarkic there is a garden for food cultivation and the wooden tower for the staircase includes solar collectors and a small windmill on the top to generate electricity. The structure is built out of the materials found in the direct surrounding: timber, limestone, mud, lime plaster.

For Auguste Rodin, reality changes as you turn every five degrees. ‘Truth’ is a phenomenon rather than an object. The reality around us should be understood in different perspectives with different layers of interpretations. Illusion negotiates between reality and perception. Reality turns into illusion gradually, and vice versa. There should be a space for hallucination, a space to ‘space out’ and a space to meander through time, as the meaning of ‘vacation’ is to give oneself time for better reflections in life and work. We need a house to understand ourselves more slowly and deeply.

The landscape of the site comes from all around, views from afar gradually merge into views nearby. Through seasons, moments of wilderness come into our “involuntary memory” (Marcel Proust) and impact the way we project ourselves into the space. The exchange, between exterior landscape—our inner self—what we create is what comprises the circle of life and work. As we are inspired by the surroundings at all times and from all directions, our life and work gets redefined constantly.

Architecture becomes a way to measure the gradient of reality, or illusion

An elliptical structure is created to mediate between our inner self and the panoramic landscape. The architecture is wrapped by a double skin wall that breathes, with circulating paths meandering between the two skins. From the interior, the exterior landscape has never stopped. It comes in and fades away. While the stationary spaces of living, sleeping, and working are animated by layers of exterior skins with overlapping perforations, the circulating path suspends the body in the residual space between reality and illusion. Landscape and body encounter in space spontaneously.

Architecture becomes a way to measure the gradient of reality, or illusion. Along with the life and work it brings, the architecture dissolves gradually into the eternal landscape of Lake Ederesee.

The Open House aims to connect people to nature, individually and collectively through using elemental forms and the elements of earth, wind, and water. Everyone is invited to inhabit this shelter to work and to live in. It is a space of slow and fundamental life.

One dives into the building through an exterior staircase, as one would enter into the silence of a forest. In the lower level, individual experiences—the smell of earth, the light of the sun, and the dripping of the rain—enter the vertical shafts.

The ground level is an open room without walls. This collective space offers protection, shade, and a refreshing breeze during hot summers for communication and playing. It is an architecture defined through soft elements.

The Open House aims to connect people to nature, individually and collectively through using elemental forms and the elements

The upper floor provides room to work, to talk, and to think. The space is for everyone—the painter, the writer, the craftsman, the priest, and the family. From here, only the relationships to the surrounding natural landscape matter—the reflection of the lake, the rustling of the trees and the smell of meadow.

The rooftop pond collects rainwater for a natural habitat of diverse plants that grow around and inside the house over time.

From being rooted within the earth, to an architecture without walls, to reaching within and above the tree canopy, the house oscillates between being introspective and externally facing. It is an open house—to people, elements, and the natural landscape.

1. The project is an attempt to minimize the footprint of the house in order to leave as much of the available plot unobstructed from construction. The plot, presently a large grass meadow, is spatially defined on two sides by the access road (south) and a pedestrian path (north) while on the other two sides by groups of trees (east and west). For this reason, rather than occupying the plot, the house is an attempt to make this open and defined ‘green room’ available through the simplest possible infrastructure.

2. The One-Room House represents the minimum infrastructure that could be placed on the site in order to make it inhabitable. Given the green character of the area, this minimum infrastructure takes the form of a pergola stretching across the site in the north-south direction. The pergola, a simple wood structure with a width of 4 meters that is to be covered with climbing or trailing plants, becomes the support of the house itself. By closing the central spans of the pergola with light wooden walls, the space of the house is defined. The remaining spans of the pergola are to be used to access the house, as shaded space for leisure and productive activities, for parking and ultimately for the potential expansion of the house.

The One-Room House represents the minimum infrastructure that could be placed on the site in order to make it inhabitable.

3. The One-Room House is imagined as one single room. Traditionally domestic space is made of a composition of rooms and each room is defined by a specific function (living-room, bath-room, bed-room). Our project proposes one single space that can be used in many different ways. As such the house is a reflection of two canonical projects for domestic space of the 20th century: Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois and Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Caanan, Connecticut. In these houses domestic space is reduced to one room but the service core acts as separé that, without dividing the space, addresses different regions of it. In our proposal the service core runs parallel to the house itself thus making the latter a single room. A system of sliding panels placed at regular distance allows the single room to be transformed at occurrence into an enfilade of rooms. Overall, the house is not constructed on the predetermined separation between living and working, but allows for a flexible use according to one’s need.

4. The house’s structure corresponds to the structure of the pergola with its wooden beams and pillars. The house’s walls are pre-fabricated wooden panels with pre-assembled insulation and external paneling. The concentration of the house’s facilities and services along the eastern edge is meant to reduce to a minimum the organization of domestic installations and thus the cost of construction.

Find out more about DOGMA's work in this feature interview published last year on Archinect.

MH House is a 34.5 square meter prefabricated shelter with a 17.5 square meter terrace and a total cost of €5,000. Its lightweight structure is made of galvanized steel. The frame is modular and parts are interchangeable. Its walls and roof feature polyolefin foam panels, which protect residents from sun, wind, rain, and snow. Its final coating, a metallized polyethylene terephthalate (MPET) is tough and durable and provides the house a unified image. Its short sides are covered with door-integrated-panels and a solar panel and a rainwater collector in the roof ensure its energetic autonomy.

Awaking curiosity, occultation, contrasting inner and outer, offering mystery, the house imagines the domestic as a game

Inside, the MH house contains a thermal curtain that surrounds four objects: a stove, a kitchen, a bathtub, a bed, and a masonry heater. An adjacent pavilion includes a chemical toilet and the water tank. During the cold seasons, the thermal curtain reduces the house floor area and takes advantage of the thermal mass of the masonry heater. During the warm seasons the doors on both sides of the house ensure cross ventilation and a direct relation with nature. Its terrace, enclosed by a bare structure soon to be covered by vines, provides a second chamber to enjoy the site’s domesticated nature.

Assembling the MH House requires a team of four people and takes four days. It uses only off-the-shelf technology and mainly appropriates components of the Better Shelter modular emergency shelter. The set of pieces to build the MH House fits in 8 flat pack boxes. Once built, MH House weighs 507 kilograms.

MH House is a fragile double pitch-roofed box that attempts to contain everyday life. It combines features of the existentialist hut in the black forest, a positivist mass-produced housing unit, and the case study houses’ pragmatic hedonism. To escape all three models MH House collages all their technologies together in a temporary magic box. Awaking curiosity, occultation, contrasting inner and outer, offering mystery, the house imagines the domestic as a game.

Find out more about Fake Industries Architectural Agonism by listening to our podcast interview with them from Next Up: The Chicago Architecture Biennial:

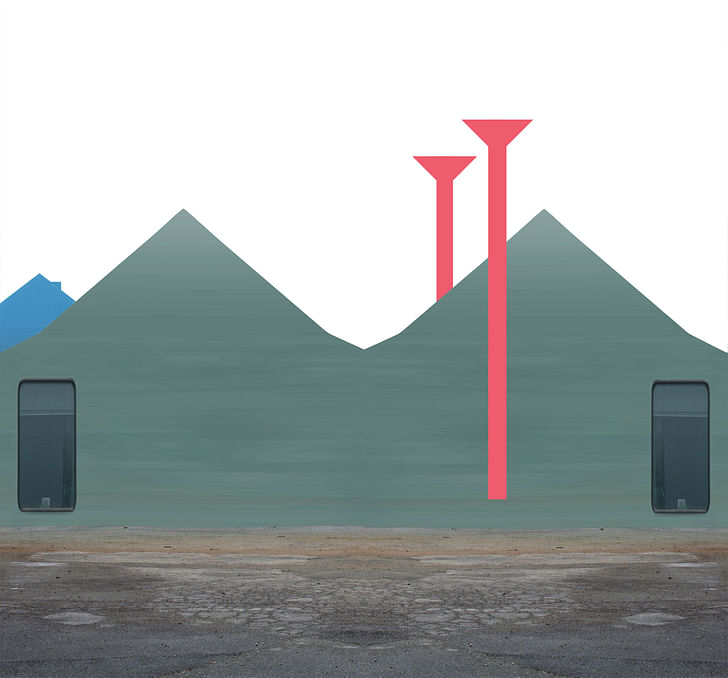

Segments is an experimental retreat for the immersion of life and work into nature. Located by the Edersee lake, the solid silhouettes stand seemingly next to each creating both, a protective exterior and a fluid interior topography that allocates the various programmatic elements. Based on a whole set of carefully designed sectional programmatic layers known as ‘segments,’ the combinatory composition of joining sectional slices allows for customized house programming and personalized interior layouts with flexible spatial options. The compact house offers a new strategy for living an individual work-life-balance, accommodating up to 5 residents in two levels and a total of 90 square meters, which configuration can be determined upon assembly.

Segments aims to provide a flexible and cohesive way of living through the connection with a natural environment to those who prefer combining work and daily activities

Both end-sections of the house are open to nature and provide direct morning and afternoon light as well as ventilation. Two sectional elements define the north and south of the building. The south section is flipped horizontally to create the main terrace and activity platforms, with a direct view towards the lake and the forest. The north section is detached from the main building and works as a discretion element and vertical screen that frames the back entrance. All segments are cast in concrete on the exterior and finished in timber in the interior, thus creating a warm and close relationship between the natural elements on which the project sits and the high standards of a contemporary housing project. Segments aims to provide a flexible and cohesive way of living through the connection with a natural environment to those who prefer combining work and daily activities.

The experimental house is an attempt to develop the living-garden house concept, which we have been working on consecutively in several executed projects. The aim is total integration with nature and dematerialization of any architectural barriers. Inhabiting living-garden is comparable to living in nature. Living-room becomes living-garden—a natural extension of the garden—hence the name of this new typology. However, so far the garden inside living-garden house has only been a substitute. In this experimental house we’ve decided to take it one step further. What if we brought the real garden with its living ecosystem into the house? What if the roof worked as a tree crown, protecting from the rain and diffusing sunlight? What would happen if we could sit, work and sleep underneath the tree, while enjoying convenience of being inside the house? What if we could live under the stars, like our forefathers?

An experimental house brings on a new quality of life—close to the nature and its variable rhythm of day and night as well as seasonal rhythm

In the experimental house functions are located in the garden on hybrid grass, giving the inhabitants a complete experience of living in nature. The roof structure consist of a steel grid filled with intelligent glass, which reacts automatically to the change of light intensity—it lets trough the exact amount of sunlight, which protects the house from overheating during the summer. In case of cloudy days or winter, the glass becomes more transparent, always keeping the view on the sky. Roof works like leafage of a tree infiltrates the light and prevents [damage] from precipitation. Repeatable modules of the roof grid are designed to be multiplied and cover structures of variable surfaces. During the day, while we want to be in contact with the surroundings, the house can be opened completely and merge into the garden thanks to the sliding glass walls. In the evening, when we need more intimacy and sense of security, we can isolate the interior by closing sliding glass walls and external shade blinds, having at the same time an undisturbed view of the sky trough the transparent roof, which sets into the mode of full transparency after the sunset. So you can be free from the neighbors’ curious glances, lying in your bed and watching the stars.

An experimental house brings on a new quality of life—close to the nature and its variable rhythm of day and night as well as seasonal rhythm. This is the return to the lifestyle, which is the healthiest one to the human being, because it is the most natural. The use of…an intelligent skin consisting of dynamically reacting glass and living grass creates an optimal microclimate of the interior, considerably reducing the need for mechanical regulation of temperature or humidity. We believe that the future of architecture is... no architecture, or rather; with the use of advanced technologies it should evolve to be as unobtrusive as possible.

‘From Roots to Crowns’ describes the vertical metamorphosis of a hybrid building, moving from below ground through fields and trunks up to the crowns. It is a living shell on the move, able to take on 3 main positions “under the earth”(-1), “on the fields” (0) and “in the tree crowns” (+1+2). The lifting house is a visionary way of adapting the concept of ‘living and working in nature’ to the varying requirements of its inhabitants.

“Under the earth,” it hides below ground, blending into the surrounding landscape, protecting, disappearing, contextualizing… “On the field” at ground level, the building is directly connected to the surrounding landscape, integrating, blurring… While “in the trees,” it radically sits among tree crowns, offering views of the Edersee, simultaneously revealing the swimming lake below, flying, soulseeking…

The building adapts to the different situations and requirements throughout the day, seasons and years

Its main focus lies on vertical and horizontal flexibility, expressed externally through the vertical movement and internally through an open plan layout. The large central patio allows the boundaries between inside and outside to disappear, functioning as a visual and physical connector between the different areas.

Furthermore the patio, balconies, glazed interiors, swimming lake, and roof-scape create introverted and extroverted spaces, allowing the inhabitants to hide or to expose the building and the life inside it.

The building adapts to the different situations and requirements throughout the day, seasons and years, thus creating a sustainable way of living and working inside nature. The plan layout follows a modular concept of easily switching various spacial combinations by emphasizing the wish of its creators to enhance a simple yet radical desire: “…it doesn’t matter where you work, sleep, eat, play… as long as you can do it everywhere.”

This is not just a house in a landscape. It is a one-person factory for an expert in the digital knowledge economy. The cosmopolitan internet-worker is suddenly also a rural dweller, and this condition offers destabilizing inversions.

The first inversion concerns the public-private gradient between the exterior and the interior. The sparsely settled landscape offers more privacy than the heart of the house: the digital space where the inhabitant works. The screens, connections, structures, and networks of the digital realm position her into a continuous mental nudity. There is no reason to provide walls and separations from the outside—she can live in full transparency to the surrounding nature. This is a formal inversion of the historical privacy gradient of any dwelling, in which intimacy increased towards the interior.

ORG makes architecture with elements: simple forms with integrated functions

The formal inversion goes further. For the inhabitant does not in fact live there—she is merely camping. The nature of her labor removes all geographical constraints on her work, and she can be anywhere. The camper is not rooted to the house, and the house itself is not rooted. Without a footprint in the earth, it cantilevers and floats.

A medieval schloss and a dam—the two mineral behemoths that define the architecture of the region—advise the form and material of the Esuoh, but it must itself remain disconnected, unplugged from the territory: simply hovering above the primitive landscape, endowed with the impossible mineral weight of the (architectural) history that surrounds it.

ORG makes architecture with elements: simple forms with integrated functions. Esuoh House is composed of six large concrete triangles which form the colossal upper mass, three highly composed wooden vierendeel beams which span and support them, two concrete cylinders which root an unrooted house, and an additional alien concrete cylinder (for the camper to evacuate), completing this choreography of elementary forms.

A life on a remote site asks for solutions of 2 different questions: How can one create a harmony of working on the countryside and living on the countryside? How can one create a symbiosis of architecture and the surrounding nature, that both can profit from each other?

To address the first question, we were looking for a typology of architecture that separates its functions, but also is able to connect them under one roof. Two halves that form one entity. One part for living. The other for working. In harmony with each other. Like yin & yang.

One part for living. The other for working. In harmony with each other. Like yin & yang.

To find a solution for the second question, we followed a principle to return the amount of land to nature that was taken away from nature in order to build the house. By a series of planters we provide a roofgarden for the residents from spring to autumn and a partly-enclosed greenhouse for the winter months.

Living on the countryside offers many benefits and growing your own food and being independent from large supermarket chains is definitely one of them. This house portrays an example to live as part of the lifecycle of nature.

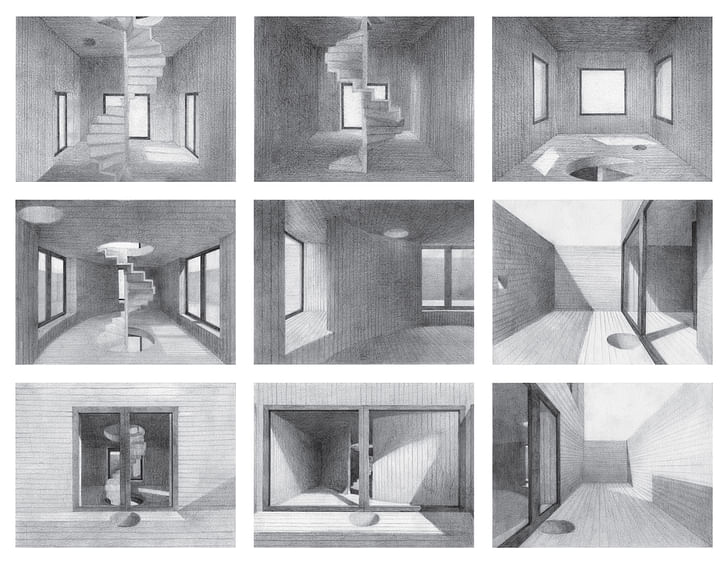

Following the current paradigm, we could live and work almost anywhere. As suspicious and romantic as this appears, we believe that the broadly-debated distinction between life and work is rather fictitious. Of course we are living while working and vice versa (at least for those who enjoy what we do). When dedicated to a single cause, living becomes a routine and, eventually, a habit. A well-placed, proportioned, lit and ventilated room, as traditional as it might be, should be more than enough for that enjoyment, for the necessary feeling of a familiar place.

A well-placed, proportioned, lit and ventilated room, as traditional as it might be, should be more than enough for that enjoyment, for the necessary feeling of a familiar place.

Thus, our proposal implies a voluntary and bucolic return to nature, to a fairly pastoral and provincial living. The house is an asymmetrical object that stresses the friction between functional specificity and spatial vagueness. An opaque and robust piece that contains a vertical succession of chambers in three levels. The first and the third are equivalent in plan and section, but with openings at opposite ends. The intermediate chamber is exaggeratedly complex: it has a lower ceiling height, an array of fixed furniture (for sleeping, bathing or cooking), a curved screen-like wall, and it is evenly extended towards independent patios in all four directions. It is precisely in that elevated domain where the intimacy of everyday life unfolds. A single spiral staircase not only articulates the transition from one spatial character to the other, but also anticipates the potential reversibility of working at home: with a shaded studio/atelier in relation to the terrain or a panoramic one in relation to the open landscape.

Ten stories’ house investigates an alternative way of living while questioning the classical concept of the villa where the sequence of generic rooms defines a domestic environment where the acoustic isolation and visual independence of the spaces facilitates the inhabitation.

Ten stories’ house investigates an alternative way of living while questioning the classical concept of the villa

Our proposal challenges this notion of fragmentation by defining one main vertical space where the program is not any more linked to a room. In the same way that a bookshelf operates, the section of the house reveals platforms at different levels that eliminate the horizontal partition between floors. The vertical communication not only happens through the stairs but also climbing from shelf to shelf, enjoying the discovery of new places of opportunity where activities can happen. Working and living spaces are connected yet independent in an organization that blurs the traditional boundaries of the different rooms. These spaces structured in an spiral configuration provide maximum flexibility while defining a circulation that allows the contemplation of the landscape in all directions in search of the water views and the long distance perspectives.

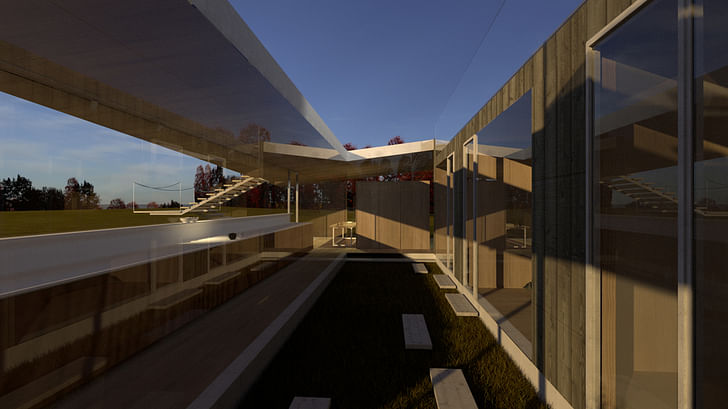

Conceived as a house embedded in a 21st century winter garden, the Perched House examines how two architectural elements—a sole service core and a perimeter wall—can effectively organize a new model of live, work, and leisure, by giving spatial hierarchy through a single volume while simultaneously dissolving the boundaries between interior and exterior.

With an elastic and porous envelope, the house can at moments be part of the open landscape while at others construct its own interior winter garden

The core—conceived as a rectangular volume that contains all services—is placed as a bar that separates social areas facing the back garden from the office space that faces the street. Towards the street, the bar accommodates an office library space with enough privacy to hold business meetings or focus on an office task. The backyard edge accommodates the kitchen and a fireplace, defining the living and dining room areas of the house. A staircase, wedged in the center of the core, takes you to the bedrooms perched above the open volume. The southeastern and southwestern walls are made up of double layered glass functioning as a ventilated air buffer, moderating the climate of the house throughout the year. During the summer, the outermost enclosure blocks direct insulation through a system of applied ceramic enamel fritting, and in the winter the air space serves as a greenhouse, protecting living spaces from extreme cold temperatures. The inner glass layer has a secondary fretted pattern that increases and decreases in intensity to calibrate privacy. With an elastic and porous envelope, the house can at moments be part of the open landscape while at others construct its own interior winter garden, adapting effectively to shifting programs and weather.

The project takes a new approach to the conventional building envelope and creates ways of life between itself. Up to 10% of a normal building footprint is occupied by walls as dead space. By delaminating each individual layer of a wall and window assembly, we are able to build on the characteristics of each part and create new spatial conditions. Louvers, fly screens, cladding, double glazing, framing, internal linings, curtains, and blinds create a series of layers which allow for increased material and climatic efficiency. Our principle is that each assembly layer, each material, each fitting, can be of greater value and use than just for its sole intended purpose.

each assembly layer, each material, each fitting, can be of greater value and use than just for its sole intended purpose

The design is a prototype, which uses an internal footprint of only 39 square meters. Occupation is flexible with the use of two separate layers of glazing. An external layer with hinge doors activates and transforms external spaces; open the living room door to create an outdoor cinema. Play spaces, vegetable ‘pantries’ and an extended dining area expand out of the internal programs to 100 square meters. By using such an approach, we estimate we can save up to 25% of cladding, internal linings, and internal framing compared to a conventional house of a similar size.

Continuing the principle efficiency, door tracks are also the rails for the fly screen, creating form out of function and conventional materials. This logic is extended from an aesthetic point of view, where the reflective properties of glass are played upon to create new spatial conditions, which immerse life on the exterior landscape into the interior.

The sloped ground is controlled through a simple field of stainless steel garden edge strips. These are manipulated to align with undercover and internal spaces, allowing program to extend and maximize use of the entire site for every way of life in every season.

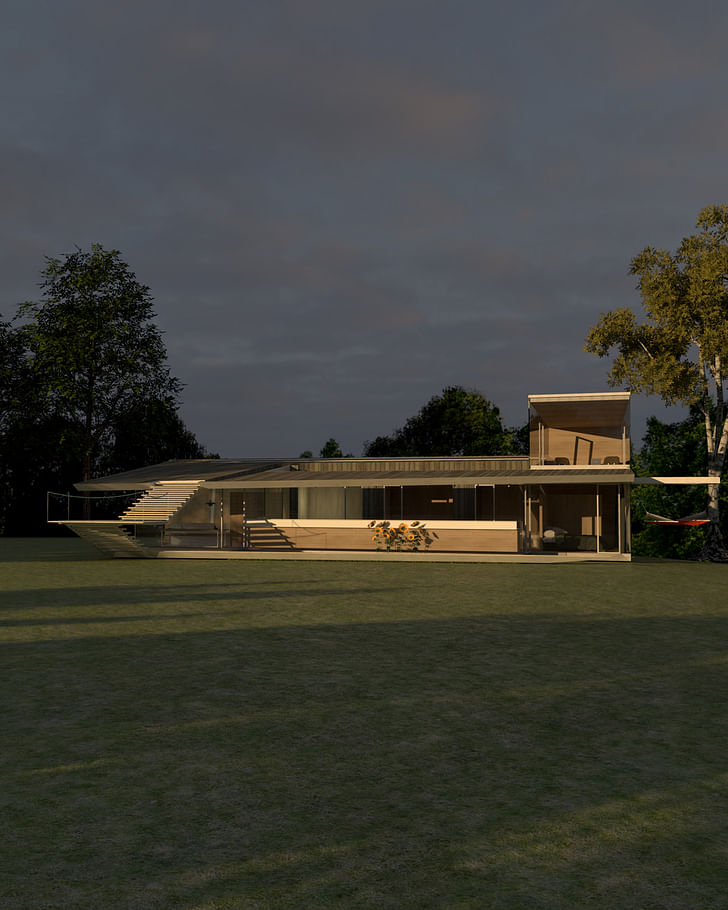

The conceptual idea for this building is a house that wraps itself around and shelters its owners, while at the same time distributing the zones and individual rooms so that they enhance the awareness of living in harmony with nature. The building is lifted gently above ground—emphasizing that the existing grassy field is left untouched. The living areas float just above the grass and eventually stretch up into the trees. The living area limits have been utilized to the maximum, but only to provide a comfortable home for a full family, which to me seemed the most interesting brief within such strict limitations.

a house that wraps itself around and shelters its owners, while at the same time distributing the zones and individual rooms so that they enhance the awareness of living in harmony with nature

The fundamental idea of the layout is that all movement between rooms is a journey in nature. The public rooms of the house are laid out between the glass exterior facades and the glazed atrium at the centre of the building. The kitchen faces the access from the street, like a traditional kitchen window. The dining room area is set behind the stairway to the roof, which provides privacy. The lowered floor of the living room is cast in concrete to contrast the rest of the building and to underline the earthbound feeling. The private rooms are positioned on the opposite side of the atrium, which increases the privacy. To access these you actually need to step outside and cross the atrium. You access the office by ascending the stairs that lead to the roof, following the recessed pathway, which takes you around the atrium to the office. Exclusively from the office you can step out on an elevated terrace that take you to the treetops. The layout of the office gives an unobstructed and private view down to the lake. The slanting solid wall provides a backrest for the sofa benches and beds.

We envisage the construction of the building in CLT with the inner layer, which also become the interior surfaces—floor, walls and ceiling, in natural untreated oak. The outer cladding in cedar panelling will turn silver grey with time.

Nowadays everyone is connected by the Internet, thinking together as one organism. But in this process of connecting with each other virtually, we have somewhere forgotten about our physical connection to one another and nature. Hence now it becomes important to connect our virtual life to the physical surroundings and enjoy it to the fullest. As Aristotle said, “Human being is by nature a social animal.” It is essential to study living through our relationships: individual to family, family to friends, and further to the community life.

The house is a manifestation of various ways of doing the same activity

Our 21st century house aims to be flexible to transform itself according to the human necessity of being isolated yet communally connected and part of a larger process in the making of our world. We understand this making through daily mundane activities that we perform, trying to connect these activities to certain emotions that arise; and then developing a ways of life activity diagram, which further evokes the configuration of 6 strings of life: connection with neighbors, self, communal & collective, semi-individuality, temporariness, family.

The house is hence a manifestation of various ways of doing the same activity and various emotions arising while performing them. It is a breathing organism, which opens out or closes, transforming according to the number of dwellers.

The result is a sum of six unique spaces, each of them with spatial characteristics closely linked to the activities happening inside them. The volumes are arranged in a spiral, where the more public of them lies in the ground and the most private is on top. A semi-covered communal gathering space is created beneath the suspended volumes.

The overlapping of domesticity and work has lead to a condition wherein we are never fully private or public, and that we are always working. Instead of an architecture that confirms this condition, we ask how architecture might in fact reaffirm these spatial distinctions to ensure the tasks of domestic life, work, public appearance, and privacy are maintained and protected. We propose a house that begins with simple geometric orders that create distinctions within the domestic/work realm to preserve their fundamental roles. We then link these diverse spaces more precisely through exterior rooms that enable an integration and separation of these realms.

Our project begins with a simple separation of the natural and artificial world through the outline of a circle

Our project begins with a simple separation of the natural and artificial world through the outline of a circle. This world is bisected with two axes that organize labor—immaterial and domestic—with equal hierarchy. Instead of hidden away, these axes—which contain the infrastructure for living and working—become the only spaces that visually open up to the exterior. Around these two axes, the project is organized into quadrants, each for an element of living—sleeping, socializing, and dining. The use of a destabilizing triangular geometry not only separates the house into introverted and extroverted spaces, it produces difference within the coherent whole of the organizational framework. The superimposition of the three geometric orders—the circle, cruciform, and triangle—are linked together by a field condition of solids and voids. The voided rooms act as mediators between the distinct spaces and increase the usable footprint of the house. Each of these spaces is then linked visually through a series of cuts, which always frame one’s relationship to the other aspects of domestic life and labor. Within this way of life, relationships are clarified internally while always put in reference to the complexity of everyday life. The house is simultaneously structured, geometric, and hieratical while being ambiguous, atmospheric, and a distributed field.

There is a big wall between urban and nature in modern society. Urban is a place where people labor, get money, and live. On the contrary, nature is a place to rest, an object to be appreciated, and where people can feel free away from the busy urban life. From the late 20th century (although there are some examples from 19th), a lot of efforts have been made to protect nature. Consequently, in one sense, nature came to be well-preserved. In addition, especially in Germany, there are some practices to make people close to nature. For example, Kleingarten is a system of plots of land, which are leased to people as a garden. Moreover, Biotope is an attempt to make a living place for a specific assemblage of plants and animals. With the help of that, green became more immediate to our life. However, nature is still set apart from our daily life. We, urban people, get up in some storied apartment, go out by trains or cars, work and shop at big buildings. We can see trees, flowers or garden, but ‘nature’ is so far beyond that we should plan a trip to be surrounded by nature. Then, how can we live with nature? Should we go to deep behind the mountains and live as self-sufficiently?

There is one thing we can do: to CULTIVATE. The etymology of labor is ‘toil’ in Latin, which means hard and continuous work, a laborious task, battle or struggle in archaic. Thus, when we labor we are controlled by something, and the job is that we must do. Therefore in this sense, we can’t feel free from labor. On the other hand, work has another etymology, ‘werg,’ which means ‘to do.’ In this point, work doesn’t have a nuance-like force. In industrial revolution times’ [urbanity], there was some small amount of rulers and people served them. Meanwhile, in today’s society, the way of working has been changed so differently, as people don’t always have to go to the office to work, and adjust the amount of work in the proper way as they wish. Thinking about architecture, slow architecture now [has to be] considered. In it, it takes a long time to build and is not necessarily efficient. It focuses the point which is not spotted by capitalism.

What we cultivate in this land is Humanism

Kleingarten and Biotope are ways to cultivate nature. There are also arrangements of natural green, attempts to make wild, strong nature, which is beyond mortal control, stay closer to human beings. Slow architecture is also a trial to cultivate industrialized world, especially house and town. That is to make urban-life a more relaxed and comfortable thing. Cultivate is not like control. When people cultivate, they arrange the soil and ground in proper way, but don’t excessively systematize it. Furthermore, while seeds grow, people do very small things to keep it well, just to help the soil and seeds. Hence people draw very rough images about the process and goal. This is similar to ‘culture,’ which has the same etymology as cultivate, and quite different from ‘civilization.’ Besides, plowing the land is a very important process when cultivating. That means to make the foundation. In terms of urban life, it can be to build house.

What we cultivate in this land is Humanism. It is a challenge to cultivate our life and recover what we lost in this time of commercialism. We, human beings, invented a lot of things and innovated our environment. In this process, we overlooked some very important things, our wish to be free. We have bound ourselves by times we set, by systems we created. Recovering Humanism is a proposal to enable us to mature our good image, which is in deep inside of our heart, and let us establish more steadily on this earth.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

2 Comments

Sturgeon's Law.

not this work though. If anything its the reverse.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.