The single-person room is the among the most basic units of architecture and the background for much of daily life. Here we project our personalities on the walls in the form of decor. Here we can retreat from the world. Yet the ubiquity and familiarity of the room nearly renders it invisible. Rarely do we consider the specificity of these places, which simultaneously serve as refuge and site of labor, of reproduction, of identity formation and presentation.

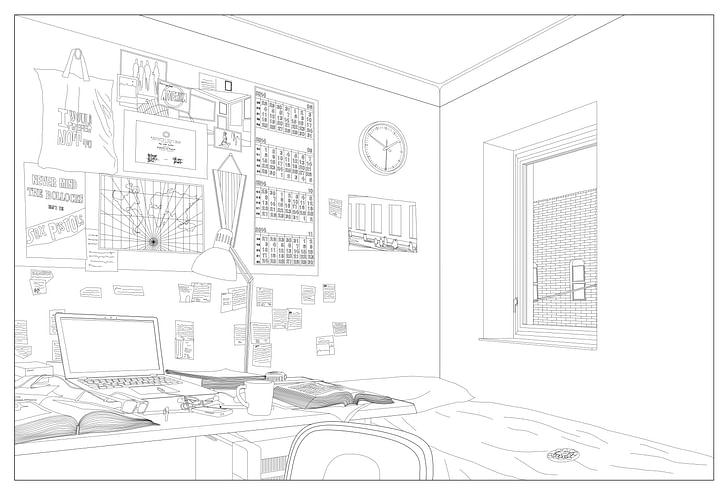

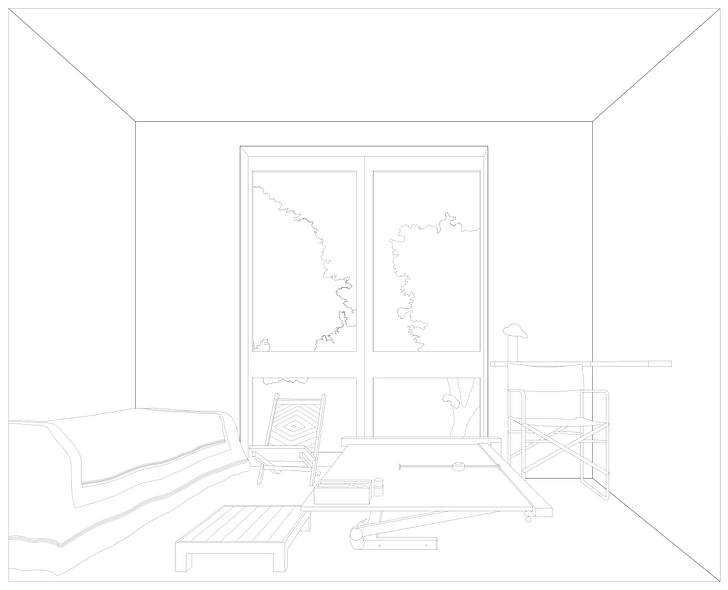

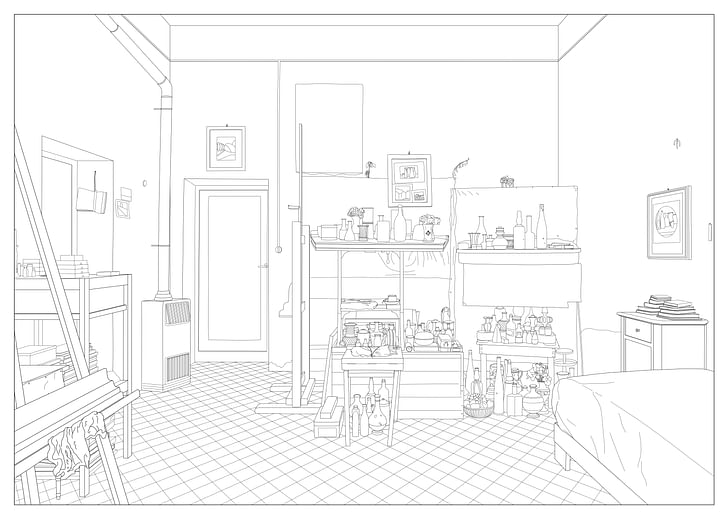

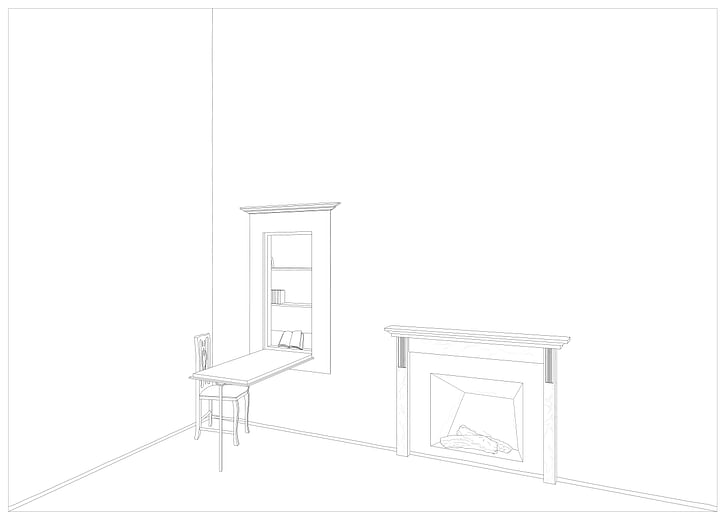

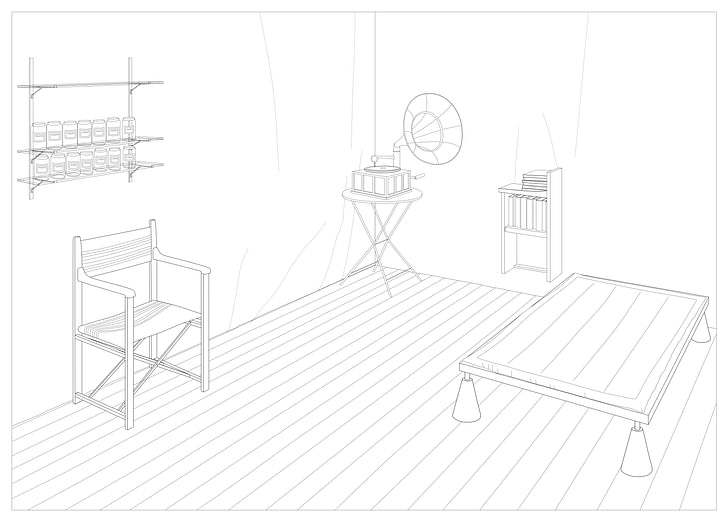

With their series Living/Working, the Brussels-based studio Dogma investigates this commonplace but essential element of architecture. A series of illustrations in the ‘ligne claire’ style, the project considers the contemporary state of the single-person room vis-à-vis its history, specifically through the dwelling spaces of famous artists, writers and architects.

The distinction between living spaces and sites of labor was formed relatively recently, and is already coming undone. A study by Reverie, a bed manufacturer, found that 80% of young New York City professionals work from bed regularly. Even scrolling Instagram before sleep is, for some, a form of income-generating labor—and it certainly generates capital for Facebook, the app’s parent company. Many of the most profound revisions to the architecture of daily life are happening not in public squares but in how we occupy domestic interiors.

Dogma was founded in 2002 by architects Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, both graduates of the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia (IUAV) and the Berlage Institute. Their practice is oriented around developing projects that allow them to focus on their “favorite topics”: large-scale design and the architecture of domestic space. “We only commit to projects whose brief allows us to develop our own research trajectory, as if every project is a chapter of a larger project,” they state. “ We always prefer to work on projects where we can eventually change or re-define the brief. After all the goal of research is to be able to change or re-formulate the brief through which the ‘need’ for a project is put forward.”We believe that history is a formidable instrument to understand the present

Alongside their work as Dogma, Aureli and Tattara both teach, work they consider extremely important to their practice. “When you teach you have to provide answers to students’ questions, but for us teaching is also a way to properly formulate questions,” they explain. Rather than treating history as a way to “legitimize design,” or something distinct from design, they teach their students to use it as a means to “problematize.” “We believe that history is a formidable instrument to understand the present,” they explain.

Living/Working well-exemplifies this approach, and, as a careful study of the forms of domestic habitation, felt particularly relevant to July’s theme on domesticity.

I spoke with Dogma via email about the thoughts behind the Living/Working project, and how it plays into their practice overall.

What was the impetus for the Living/Working project?

Living/Working refers to the increasing identity between life and work, life and production, and how work is today no longer a specialized activity but rather invests the whole spectrum of social life.

We started this research a few years ago because we have always been interested in the relationship between labor and architecture. When we talk about labor we immediately think of the traditional workspace such as the office, the factory and the workshop. Yet the primary place of labor is the house. labor is the sheer unending stream of activities that are necessary for the reproduction of us as speciesIn essence labor is the sheer unending stream of activities that are necessary for the reproduction of us as species (cooking, eating, sleeping taking care, raising kids). Labor is thus primarily reproduction: the reproduction of labor power, the labor that capital exploits in the office, the factory, in the university and elsewhere. Yet as it has been noted by many, and especially by feminists, capital has never paid for reproduction, making the latter a ‘natural’ condition of our life.

It is interesting to note that ancient civilization such as the Greeks and the Romans considered labor as defined above an unworthy activity because, unlike the work of an artist or a poet, laboring activities do not produce lasting things. It is for this reason that both the Greeks and the Romans justified slavery. Slaves were those living beings whose terrible fate was to spend their existence only for the sake of maintaining the household. Here lies the original purpose of the concept of the family, the essential protagonist of domestic space. Family comes from the Latin word famuli, which address a congregation of slaves and relatives headed by the master (the pater familias). Family may evoke the warm feeling of affection and intimacy, but its original purpose was to organize reproduction under despotic relationships such as those between father and son, husband and wife and master and slaves.

The naturalization of domestic labor has been achieved through a specific ideology: the ideology of domestic space as a space of retreat and intimacy unburdened by working relationships. Today, the separation between house and workspace is in decline as production unfolds everywhereThis is why under capitalism there has been a separation between the house and the workspace as two distinct spaces and typologies. Only activities that would happen within the workspace were recognized as a ‘work’ and thus performed in exchange for a wage, while everything that would happen in the home would be considered non-work and thus reproduction has always been exploited by capital for free.

Today, the separation between house and workspace is in decline as production unfolds everywhere. Many people, especially freelancers, professionals etc. tend to work at home and thus domestic space is again a workspace. Yet as we know freelancing work is increasingly precarious and often unpaid. Ironically (and perhaps tragically) the model of domestic labor as unpaid activity has become the model for work in general, so that an artist or a poet may work for free at home. Even contemporary workspaces tends to increasingly resemble homes: think of start-up co-working space with their plethora of sofas, kitchens etc. While it is easy to make of all this a bleak picture, if the house is an apparatus of exploitation then it can also be a place of resistance and the construction of new dwelling habits freed from the tradition of the house as ‘domestic’ space. Through texts, drawings and projects that challenge the house as privately owned by a typical family, we try to put forward an alternative project for housing beyond its domestic identity, where reproduction can be organized collectively.

How did you choose the figures whose rooms you illustrated?

These illustrations of rooms are an attempt to trace a history of one of the most elusive architectural element: the room. In spite of the fact that the room is a quintessential architectural element, there is very little research that specifically addresses this kind of space. Of course there is a plethora of books on ‘interiors’, but they often take for granted the specificity of the room as a dwelling space.

The selection focuses on the single person room, the room as a primary space of existence, where dwellers may have the possibility to be alone. Since our Living/Working research focuses on the possibility of communal living, we believe that living together is only possible if there is always the possibility to be alone, if each dweller has the possibility to retreat in solitude.we believe that living together is only possible if there is always the possibility to be alone

Typologically the single person room can be traced back to the monastic hut or cell—the word monk comes from the Greek monos which means alone—but its diffusion in the 19th century was due the emergence of the boarding house as a living accommodation for single workers. (We have analyzed this specific typology in a small book recently published ). Of course rooms for personal retreat existed in wealthy houses in the form of the studio, the cabinet or the boudoir. These spaces were often a place to escape not just the world but also the burden of domestic life. In analyzing this specific type of room, we are interested in questioning the whole idea of the room as the basic unit of that form of living that we call the ‘apartment’.

Even though the house as ‘apartment’ (i.e. composition of rooms) has a long history, the emergence of rooms as strictly specialized spaces—such as the bedroom, the bathroom, the living room, and the kitchen—is a product of the way the nuclear family was engineered in the 19th century in order to provide an efficient and smooth space for reproduction. The room is thus a space of individuation, a space that defines subjects and gives them a role within the house (parent, son, daughter, servant, guest). At the same time the room can also be a space of resistance against this logic.

The word ‘room’ comes from the old English rum, which means, similarly to the to the German word raum, ‘space’. Both words are very close to the Latin word rus, which means ‘open country’. This meaning exists in many other languages in which variations of the word rum designates an open field, or open plain, or the act of making space. The word itself addresses a semantic field in which someone is capable of clearing space for oneself. In our research we were very much inspired by both Louis Kahn evocation of the room as space where one is confronted with the most basic properties of architecture (dimension and structure) and by Virginia Woolf’s famous essay A Room of One’s Own, in which the English writer stated that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”being alone is a rather disruptive act that emerged only when the reproductive logic of the household was put into question

Similarly to Kahn, Woolf links the room as individual space with the possibility of concentrating. Yet for Woolf the possibility of having a room for oneself is linked to the struggle of woman’s emancipation from the patriarchal structure of domestic space, in which since antiquity only the wealthy paterfamilias were granted the possibility of having a space to be alone. Woolf’s claim of the room as a space of one’s own indirectly questions the essence of domestic space as space for reproductive labor where all the rooms—bedroom, bathroom, living room—are meant to support the management of the household. Against Kahn’s evocation of the room as a timeless concept of architecture, Woolf’s Room of One’s Own is a reminder of how being alone is a rather disruptive act that emerged only when the reproductive logic of the household was put into question. Moreover, Woolf likens the possibility of a room with the possibility of economic independence, thus linking the space for solitude and concentration to the wider class/gender framework through which society is organized.

Are all these rooms historically preserved?

This is an interesting question. Some of the rooms we have drawn are preserved, because they were rooms of famous artists or writers whose house has been preserved—more or less—as it was left when they passed away. This is reminiscent an old tradition that used to be very strong until very recently and which consisted in preserving the room (sometimes even the house) with all its objects and furniture as they were left by the deceased inhabitant. This is the case of Woolf’s writing lodge which was preserved by her husband after her suicide. The preservation of domestic interiors as memorials is interesting because it shows how the world of domestic objects which we normally assume are ‘commodities’ can becomes also affective things, tools through which the human animal construct his/her own world and biography. In some case the rooms were just ephemeral mise-en-scène such as Hannes Meyer’s Co-op interior, which is known only through a photograph. Or in other cases the room is a reconstruction, such as Marcel Proust’s famous cork-lined room exhibited in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. interiors are the most fragile architecturesSometimes we also draw imaginary reconstructions such as the ‘Room’ we have drawn as illustration for Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener and which was inspired by the room of a contemporary intern.

We also look at paintings and old photographs for our reconstructions since interiors are the most fragile architectures. As you may know, preservation has until recently focused only on monuments or outstanding artifacts, and only when it comes to famous dwellers their rooms or houses have been preserved and often entirely reconstructed. Yet, in our research we are not so much interested in the issue of preservation, but more on how these interiors can give us a glimpse of the ethos of those who live there, their habits, their rituals, their role in transforming these given spaces into their own spaces. When we say ‘their own spaces’ we don’t mean it in the sense of property, but more in the sense of use and affection.

What do you hope to convey with these illustrations?

We hope to convey the fact that rooms are not just a space of intimacy, but social and political artifacts. These rooms are always clashes between processes of individuation and control and possibilities of retreat and creation.

It is telling that Meyer constructed his Co-op interior as an illustration for his own famous manifesto “Die Neue Welt” (‘The New World’) which describes what the new world means for him. These rooms may invite us for a moment to think the political away from its canonical spacesIn this example the single person room (and not the city) becomes the place where it is possible to assess a general condition, the ethos of an epoch.

These rooms may invite us for a moment to think the political away from its canonical spaces (public space, or electoral debates) and think of it in terms of the ethos on which the construction of specific form of life becomes a (political) project. In these drawings a great emphasis is given to objects which we try to render as precise as possible using the ‘ligne claire’ drawing technique we borrowed from Paul Letarouilly and Leon Krier.

These rooms tell us how certain typological conventions were actively subverted, like for example in the case of Giorgio Morandi’s studio, which was his bedroom. Even when Morandi became a famous artist he never abandoned his own bedroom and refused to work in a studio.

This interview falls under Archinect's July theme, Domesticity. For more domesticity-related features, head over here.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.