This is the second half of a two-part interview with Cryptome, an online repository of leaked government secrets and other documents relevant to contemporary surveillance and its infrastructure. Cryptome is run by the architects Deborah Natsios and John Young, who live and work in New York City (any use of the first person is from Natsios' perspective). Part one, which you can read here, delves into their backgrounds and motivations. Part two deals more with their views on the contemporary city and the politics of information access.

I was hoping you could draw something like a sketch of the city as you see it today, perhaps using New York, where you both live and work, as an example. How does surveillance operate in the city? How does information become a mechanism of control? I'm thinking a bit about your recent postings on Twitter of surreptitious surveillance cameras.

Our place of work overlooks a long stretch of historic Broadway, the city's oldest north-south thoroughfare and a former native trail. Broadway charts a diagonal exception to the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, which famously overlaid a rectangular grid as a rationalizing technique to discipline wild Manhattan's island topography.Vibrant democracy has to make public space available for the unexpected, the creative, the dissenting without fear of reprisal

Broadway's everyday percussion of taxis, fire engines, ambulance sirens, garbage trucks, barking dogs and toddler tantrums that reach our windows confirms that, in spite of the grid, eruptions of near-chaos have always been part of the creative hardscape. It's only when we join the anarchic materiality of street-level democracy as autonomous, anonymous or social pedestrians that we feel truly embodied in the living city. Vibrant democracy has to make public space available for the unexpected, the creative, the dissenting without fear of reprisal.

Not visible from our upper aerie is the concealed architectonic of municipal grids superimposed in recent decades onto legacy disciplines of 1811. We cannot see vast information infrastructures that encode processes of worldwide economic restructuring whose capital, symbols, goods and bodies flow through the local interests of our relentlessly global city. Harnessing informational flows falls under the trending rubric of municipal 'smart' policies.

Metropolitan governance has widely embraced market-driven best practices derived from global risk management approaches, as David Lyon notes. Their privatizing regimes are anticipating and controlling urban outcomes through risk calculations that mine big data from myriad sources. Most provocative are analytics gleaned from ubiquitous watching and tracking of bodies that make up the city's far-flung, mobile and diasporic populations. We are increasingly visible to invisible regimes. Cryptome's library for information equality works in small, daily increments to invert this diagram.We are increasingly visible to invisible regimes.

As part of modest efforts to do our part to help shore up the diminishing public domain, Cryptome has been documenting in recent weeks the block-by-block smart upgrading of New York City's obsolete public telephony system. Trenches are being chopped along the street, rope pulled through underground innerduct, rebar placed to receive poured concrete, galvanized steel pedestals positioned with orange power cable and fiber poking out of conduit.

Installed onto the legacy footprint of the city's former sidewalk payphone system, 7,500 to 10,000 'Structures' of the dispersed LinkNYC system will broadcast 'relevant' ads on 55” HD screens to subsidize the kiosks' free gigabit-speed Internet service, free public wi-fi, free domestic phone calls, free USB phone-charging outlets and a 911 emergency call button.

Assemblages like these undergird smart cities that are consolidating around us, with boosterish zeal, for the supposed benefit of municipal efficiency, convenience and social equity. Big data collection technologies that enable the Internet of Things (IoT) are embedding into larger scale urban infrastructures towards that end.

But can smart space be democratic public space when speech and acts are ubiquitously recorded and reported? Are apps 'free' when they harvest vast troves of personal data without consent? can smart space be democratic public space when speech and acts are ubiquitously recorded and reported?Wi-fi hotspots are notoriously insecure. Smartphones exude communications trails and geolocational clues. LinkNYC's multiple onboard sensors include microphones and concealed pinhole cameras that capture ambient data for 24/7 delivery to downstream analytics.

Surveillant practices capture and process our digital traces as abstracted New Yorkers, fragmenting personal data into simulated identities stored in various databases or resold to data brokers. Jury pool lists, marriage licenses, voting records, civil disobedience misdemeanors, rifle permits and police dossiers––analog bureaucratic records that constituted an earlier idea of civic modernity––are now logged electronically. They coordinate with other databases, both commercial and municipal, through powerful data-mining analytics that reinforce the social partitions and economic divisions of the inequitably stratified city, as Lyon warns.

During the 1960s, Jane Jacobs advocated 'eyes on the street' as a citizen-directed management of public space that invited watchful caring of neighbors and strangers. New Yorkers could make 911 calls seeking emergency assistance from the analog payphone system first installed in the 1920s.

After 9/11, the NYPD deputized New Yorkers as para-policing informants, urging them to act on fear and suspicion: 'if you see something say something'. The vintage payphone system had fallen into disuse. Post-9/11 visualization and reporting regimes revealed risk management-style policing coordinating with command-and-control technologies developed for military battlespace and cyberwar. Preemptive war-gaming targeted Muslim neighborhoods of Bay Ridge, Pakistani communities along Coney Island Avenue, public housing in the South Bronx and Bangladeshi enclaves in Kensington.

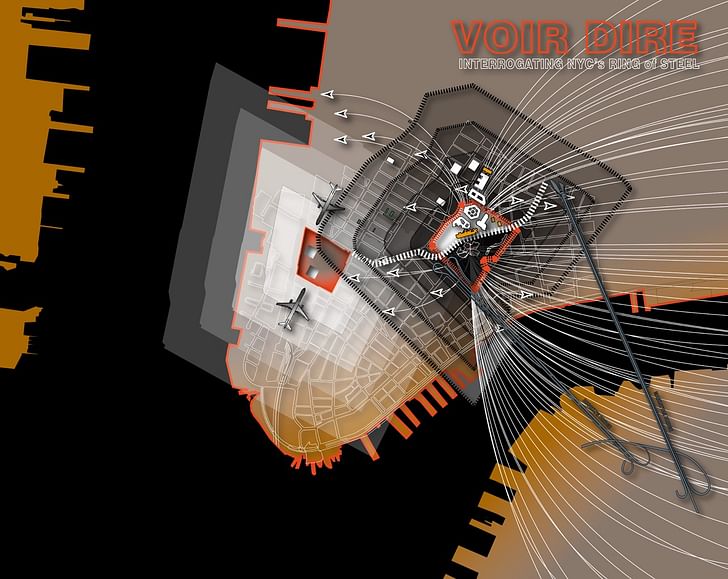

A company that produces military mission control systems manufactures LinkNYC kiosks through a spin off entity. Installed along public sidewalks at a granular coverage of every 200 feet or so, the devices introduce an unprecedented urban apparatus: the coordinated automation and privatization of neighborhood-scale sensing and reporting derived from military command-and-control technology. Has LinkNYC been tracking Cryptome's movements through the city?LinkNYC joins stop-and-frisk policing and Lower Manhattan's Ring of Steel security cordon as one of the city's premier sensing and reporting technologies.

We invite LinkNYC users to challenge fine-print vendor claims that kiosk sensors will not collect data from or about consumers. That facial recognition technology will not be used. That video footage of the surrounding area captured by kiosk cameras will not be kept for longer than seven days “unless the footage is necessary to investigate an incident.” That video will not be shared with the city or governmental law enforcement “unless legally required to”. That “we will not use our cameras to track your movement through the city”.

Has LinkNYC been tracking Cryptome's movements through the city? This past week, their management representatives suddenly appeared at an installation we had been documenting on a social media platform to which they had access, and tried to prevent us from continuing our photographic survey. Civil liberties afforded by the sidewalk's context as still-viable public space ultimately prevailed.

Going off that, you were the first to coin the term 'reverse panopticon' to describe a contemporary relationship between the subject and the surveillance state. What does this term mean? How have traditional paradigms of surveillance––and, by extension, control––changed?

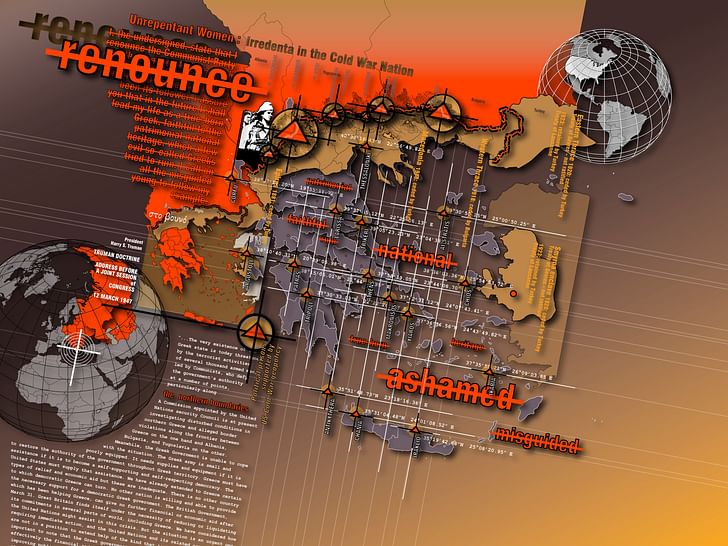

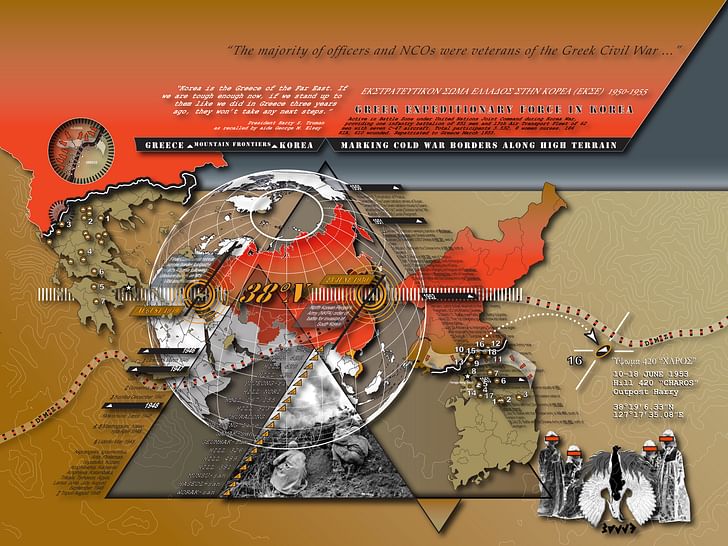

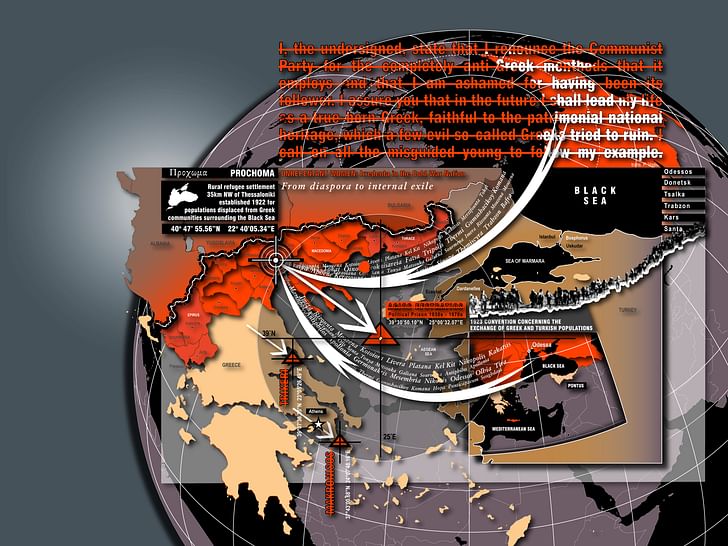

Reverse engineering forensically extracts, inspects, improves or contests 'design blueprints' embedded in manmade systems. Cryptome reverse-engineers the technics and codes hardwired into panoptical information and communications technologies as a way of examining their diagrams of power. This 'revolt against the gaze' is our tactic in the Eyeball Series when flipping the technology of national security vision back onto itself through reversals of geospatial imagery. Or reversing top-down geopolitical maps through countercartographies that favor micro-historical method. It's also Crytome's general approach to the everyday, incremental construction of a public domain library around the inchoate classification of so-called banned documents.We like to ground our strategies in ongoing maneuvers across local terrain.

We like to ground our strategies in ongoing maneuvers across local terrain. Past operations have included forays to Rikers Island, the correctional dystopia that produces New York City's mutually interdependent classifications of law-abider and outlaw. The grim complex of ten city jails sequestered in the East River near LaGuardia airport houses accused awaiting trial who cannot make bail, and those serving sentences of under a year. Rikers has been rated one of the country's ten worst jails. As presumed beneficiaries, New York City's law-abiders participate as unwitting proxies in the site's carceral practices.

We once visited an open-plan setting at Rikers where chronic jail overcrowding was being relieved by allowing inmates freedom to mill about a bunk bed dormitory instead of being confined to traditional cells. Correctional officers herded us into a central observatory from where inmates were optically monitored through a transparent surround of two-way glass. The arrangement evoked Foucault's description of the "machine for creating and sustaining a power relation”.

In a graphic performance that directly implicated visitors in the correctional gaze and its diagram of power, we watched inmates lining up on the other side of the glass partition from our observant position. With obedient self-regulation, each individual waited his turn to draw for personal use squares of toilet paper from a roll mounted centrally within the viewing wall that separated correctional staff from offenders. Vision and excretion had come into perfect architectural and political alignment. Plumbing fixtures mounted off to one side of the dormitory space were not enclosed by privacy partitions.

How did this politics of the docile body––with its regulation of body fluids, with its biometrics measured in unit squares of toilet paper, with its degrading violation of privacy––intersect with Foucault's theorization of panoptical discipline? Was the subordination displayed to visiting strangers a kind of public spectacle normalizing some new relationship between punishment and the political anatomy of the body?Vision and excretion had come into perfect architectural and political alignment.

Evidently, the provisional freedom and mobility granted the inmates, the communality of an open dormitory setting, the presumably egalitarian two-way visibility of the glass came at a price. The degrading tracking of anatomical flows suggests new codes of coercive intervention against the body. This scenario of control exceeded that of mere panoptical discipline. Deleuze has described the shift between the society of fixed panoptical disciplines and our mobile society of control where, rather than architectural walls, codes and tracking predominate.

Our reverse-engineered reading of the embodied endgame at Rikers revealed a scenario of control overlaying the legacy carceral diagram. We take this diagram as a warning of the profound challenge to HSW ethics inherent in furtive design blueprints like those embedded deep within the LinkNYC kiosk. Tracking functions and keywords may disembody the docile subject and project fragmented identities onto the database and watchlist––only to be re-embodied through degradation as a Rikers Island outlaw.

You've written before on the role of public art and museums, in particular the New Museum, as vehicles for the privatization of space and the exclusion of certain bodies. Can you speak to this? Can the same be said of other 'cultural objects', such as buildings designed by so-called 'starchitects'?

As a waystation to approaching the New Museum of Contemporary Art on Manhattan's Lower East Side, we recommend launching your itinerary five miles away along the gritty post-industrial streets and scrapyards on either side of South Brooklyn's Gowanus Canal. Despite the best efforts of its flushing tunnel mechanism, the canal is the city's most toxic spot and the country's most polluted waterway. An archaeology of Gowanus sludge reveals what a century as a dumping ground for urban industrial waste can offer by way of noxious flow. Contaminant byproducts of foundries and shipyards, the processing of coal, chemical dyes, leather, concrete and gas have left signatures long after the obsolescence of industrial and manufacturing plants.

Because this evolving industrial-to-residential zone has been a destination for artists squeezed out by a tough real estate market from studio spaces elsewhere in the city––including from the New Museum neighborhood itself––Gowanus is a good spot to consider the grueling life-cycle and industrial grade flows of cultural production: the products, the profits, the toxic losses.What pernicious urban byproducts of cultural processing are accreting in the creative city?

What pernicious urban byproducts of cultural processing are accreting in the creative city? Allen J. Scott has pointed to the heavy social costs of two-tiered creative cities unfolding within cognitive-cultural capitalism. The gap between the creative class and low wage service underclass inflected by gender, race and ethnicity is widening. Star architects “sign” idiosyncratic buildings as part of global branding campaigns built onto such exclusionary stratifications.

Each October during Gowanus Open Studios Day, culture workers welcome visitors heading to the district's enclaves of adhocked, self-organizing studio collectives. Finding affordable studio space requires ingenuity and is the necessary preamble to further creative processing: priming canvas, blocking screens, firing up kilns. The artist's investment in neighborhood fabric embeds the studio into shifting patterns of urbanization and socio-economic exclusion. We commented on some of these shifts in Bowery Ghost Ships.

Consider the concrete self-storage facility at 183 Lorraine Street, Brooklyn. Completed in 1923, the five-story fireproof structure is zoned M1-1 for industrial and manufacturing use: “light industrial uses, such as woodworking shops, repair shops, and wholesale service and storage facilities.” In recent years, the self-storage company's third floor has been converted into an astonishing warren of rental 'artists studios'. Don't even think about natural light. Most studio spaces are windowless interior cells strung along stark, double-loaded corridors. Studios cannot be distinguished from self-storage spaces of the building's others floors where urban consumers stockpile jettisoned accumulations.

What motivates sculptors, painters, printmakers and ceramicists to submit their labor to a carceral framework superimposed onto the very terrain where the factory model once disciplined industrial workers?

From their nodes of power in global flows that link networked artworlds and creative cities, the curator at the the New Museum, the Whitney or MOMA casts omniscient vision across a key terrains of operations: the exploitable natural resource of unknown artists whose very invisibility in the broad spectrum of culture workers helps validate the high-end market valuations of 'major artists'. Subordinated in windowless studios, unknown artists obediently internalize the curator's gazeSubordinated in windowless studios, unknown artists obediently internalize the curator's gaze, projecting through inner windows of their imagination fleeting prospects for recognition and affirmation awarded by auctions, art fairs, festivals, group shows and collector desire.

We once provided architectural services to the estate of a celebrated twentieth-century artist whose works were being posthumously stockpiled in a climate controlled, secure warehouse outside the city. The sequestering of the priceless cache under watch of an onsite curator meant art market supply and demand cycles were being monitored as interactively as the ambient humidity, temperature and air filtration readings being logged by automated controls onto the facility's computer hard drive. Intimations of death and oblivion linked this posthumous storage crypt with the Gowanus artist's unlit self-storage cell.

Back at 183 Lorraine Street, having exploited culture workers as stalking horses to increase the value of derelict industrial properties, luxury developers at some point will begin to prepare their raft of eviction notices. A new layer of detritus––torn canvas, shattered plaster and ceramic shards––will be discarded into the toxic dumping grounds of post-industrial consumer waste.

The mortgage for 183 Lorraine Street––listed at $2,457,946 in 1988; $10,000,000 in 2004 and $14,000,000 in 2012––is currently recorded as $28,000,000.

Cities today often exceed in influence the nation state to which they ostensibly belong. Moreover, their police forces often act beyond the confines of the municipality, sometimes even to the point of becoming global forces. What does this mean for urbanism? For students and designers of the city?

Slip into your orange safety vest. Put on your hard hat. Climb down that narrow ladder past a manhole that leads into the chaotic system of aging vaults and mainline ducts that house New York City's underground telecommunications cable systems. Lead-sheathed copper phone lines once ruled this dark and crumbling netherworld dating from 1891. You'll now find fiberoptic and coaxial cable squeezing past scraps of deactivated copper. Cabling is so tightly wedged in maxed-out ducts that new lines being pulled through conduit may be lubricated to overcome friction. Designers of the city need to overcome desktop friction and commit to rediscovering the material urban environment at this granular scale.

Fiber that links Europe with telecommunications backbones of New York City crosses the ocean floor in undersea cables that make land along the nearby Atlantic coast. After twists and turns inside subsurface urban conduits, and after transiting through meet-me rooms in colocation hotels where providers exchange data traffic, fiber is delivered to the local end user. Slip into your orange safety vest. Put on your hard hat.We track the political dimensions of some of these urban circuits in MEET-ME at Your Riser.

Knowledge economies are built upon such huge assemblages of urbanizing infrastructure vaulting across world space, channeling transnational circuits of capital, communications, data, ideas and bodies. Global cities like New York, of course, are key hubs within accelerating local and global infrastructural patterns that have made our century predominantly urban for the first time ever.

Policing practices integrated into the risk management of vast assemblages have profound impacts on lived cities. This is the case with Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP), a program that privileges infrastructure sectors serving what are deemed to be vital national interests.

Collaboration and coordination between jurisdictions of policing are required when deregulated networks dominated by multinational corporations cycle across many geographic scales and nation-state boundaries. In the case of telecommunications systems described above, managing risk of terrorism and cyberwar at federal and local scale means building in resiliency and securing vulnerable architectures. It also means anticipating and managing risky communications surging through worldwide networks. Towards this end, surveillant technologies with national security origins in signals and communication intelligence will mine data streams during ongoing CIP risk calculations. With its full coverage of public streets throughout the city, the LinkNYC matrix of sensors is a potentially powerful cyberwar system in this regard.

What role should designers of the smart city play in shaping urban conditions for a public domain of civil liberties?

Students of the city will note that politics and policing in support of CIP routinely target nonprivileged urbanization while regulating privileged global networks and flows, as Stephen Graham points out. What role should designers of the smart city play in shaping urban conditions for a public domain of civil liberties? Whether marginalized within global cities or along remote peripheries of distant continents, non-privileged urbanization is preemptively criminalized as a likely producer of sinister 'bads' infiltrating the flow of goods that drive global economies and consumer desire. Travel, communications and remittances are risky mobilities when they flow between the political turmoil of remote homelands and the diasporic local. In New York City, categorical suspicion preemptively red-lines immigrant communities linked to Global South conflict diasporas, whether in Bay Ridge, Coney Island Avenue or Kensington.

The NYPD Intelligence Division was reinforced after 9/11 under the leadership of a former deputy director of operations for the CIA. It keeps tight watch over diasporic neighborhoods in the city and beyond. Local efforts coordinate with the division's International Liaison Program (ILP), which posts officers in a counter-terrorism capacity in at least 11 overseas cities. Remote agents may patch into daily data feeds and imagery that cascades onto the monitors of the revamped high-tech war room at the Joint Operations Command Center attached to Police Headquarters. With court approval and the flip of a switch, the omniscient LinkNYC system may also be patched in this militarized centroid of command-and-control.

The nation-state does not willingly relinquish its claim of authority or massive budgets in matters of national security, however. Federal officials declare the International Liaison Program to be ineffective and routinely criticize it for operating outside the authority of US officials at home and abroad, for lacking national security clearance, for confusing foreign law enforcement officials with its non-state overseas presence. NYPD invokes its own state of exception by pointing out that the attacks of 9/11 demonstrated the failure of federal defense and intelligence agencies to protect critical infrastructures that sustain the global city.

I'm interested in the distinction between access and legibility. Does it matter if the information is out there but nobody understands it? Or, if only a limited group understands it?

These are compelling questions. We recently gave a talk at the Pratt Institute School of Information, a program founded in 1890 as a school of library science. Incidentally, that date coincides with the installation in 1891 of the underground conduits described above that have become key telecommunications backbones of the informational city. 19th century libraries and communications infrastructures have come into provocative new informational alignments in the 21st century.

It's no surprise our talk at Pratt was hosted by a class on information policies and politics. Information science programs are very busy these days sorting through politicized distinctions between knowledge, data, intelligence, information, propaganda, misinformation and disinformation. Who defines it? Who produces it? Who consumes it? Whose interests benefit from it? What can be said of the public domain or public space in an era of splintering publics?

Mass marketing techniques deploy a single strategy to capture the broadest common denominator of information consumers. Niche marketing thrives on cultivating segmented information publics. Top-down is countered with bottom-up. One-to-many is challenged by many-to-many. The explosion in social media supports the claim that 'publics create themselves and control the messages to which they are exposed.' This is presented as a democratizing dynamic. Rigidly top-down, authoritarian models of information dissemination that encourage docility in reading publics are no longer trending.

What are the implications for the commonweal when the information economy is highly segmented and the informational city spatially stratified? What can be said of the public domain or public space in an era of splintering publics?

You've been criticized in the past for not censoring, or limiting, what you publish. What's your response to this?

Cryptome's takes a pretty firm stand as a public domain library focused on debating the category 'banned information.' As mentioned earlier, this approach is consistent with Jefferson's declaration that free access to knowledge is fundamental to democratic self-rule, and critical to transforming the subjects of kings into citizens of a republic. Early modernist architects attached similarly egalitarian motives to their use of glass transparency. We don't claim to be experts, and don't espouse a top down, authoritarian model of information dissemination. The collection relies on feedback loops from below that allow engaged readers to help vet the value or authenticity of documents. It's an ongoing collaboration supported by networked social platforms. Cryptome's modest declassification project occurs in a vastly asymmetrical information ecosystem

Cryptome's modest declassification project occurs in a vastly asymmetrical information ecosystem. The national and military intelligence budgets for 2015 total $67 billion. Cryptome receives the occasional donation of $100 for its USB flash drive containing the 1996-2016 archive of some 101,000 files.

A First Amendment specialist recently characterized the imbalance in the Washington Post: “Excessive government secrecy—inherent, instinctive, utterly unnecessary and often bureaucratically self-protective—is poison to the well-being of civil society.” The National Archives points out that documents currently under declassification review from the presidential libraries alone would circle the earth twenty-five times. That a democracy should buy compromised by such interplanetary magnitudes of prohibited information is staggering. Cryptome circles this vast universe of dark matter as a tiny meteor.

Finally, why should architects care about surveillance and privacy? How can Cryptome be a resource for architects?

We argued above that vibrant democracy has to make public space available for the unexpected, the creative, the dissenting without fear of reprisal. Architects have always serviced the aggrandizement of oligarchies, theocracies and dictatorships. For architects serving a robust democracy, however, creativity is form of vital dissent from fading social, political and design solutions. When surveillance configures a diagram of power and control, it restricts democracy, the public domain and private spaces of dissenting creativity with threats of reprisal.

We welcome architects to use the transparent content of all public domain libraries including Cryptome's in any creative way they see fit.

This feature is part of Archinect's special thematic focus for June, Privacy. For more on the changing meaning of privacy in the digital age, check out other features.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.