The Deans List is an interview series with the leaders of architecture schools, worldwide. The series profiles the school’s programming, as defined by the head honcho – giving an invaluable perspective into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty and academic environment.

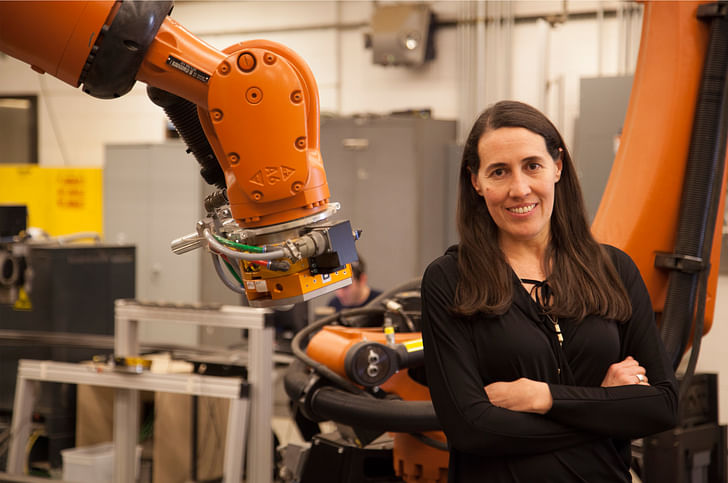

For this issue, we spoke with Monica Ponce de Leon, the Dean at University of Michigan's Taubman College.

Since starting as Taubman’s Dean in 2008, Monica Ponce de Leon has made two priorities paramount: populate a pioneering digital design lab, and strengthen studio as the central and all-pervasive educational device. In the years since, her goals are bearing fruit, bolstered by the University of Michigan’s world-class research institution and a clear-eyed view of the architecture profession.

Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning enrolls a sizable 600+ students, operating mostly out of University of Michigan’s Ann Arbor campus. The small town-vibe and the University's research brawn provide a playground take on the academy, where students have an incredible berth of resources while keeping their community relatively insular. When I visited Taubman to talk with Ponce de Leon, familial terms regularly cropped up as she spoke of the school’s community and resources. The Digital Fabrication Lab, aka FABLab, was half-jokingly referred to as “Monica’s baby” – which it really is. Prior to joining Taubman, she was the Director of the Digital Lab at the GSD while also serving on the faculty there in the late 1990s, so she has a history of “parenting” such resources. While working on FABLab, the resource has expanded to include (among the expected CNC machines and laser cutters) a host of robotic automation tools and rapid prototyping machines, and even a CNC knitting device.

Ponce de Leon has also renewed Taubman’s commitment to studio as the core tool of design education. Adamant that research and creative practice aren’t mutually exclusive, Ponce de Leon started the Research Through Making program in 2009, awarding faculty with seed funding to create and exhibit work with students. It’s also an ideology that Ponce de Leon herself practices, running her own firm, MPdL Studio, out of three small offices in Ann Arbor, Boston, and New York City. I interviewed Ponce de Leon at Taubman last year, with follow-ups through February.

Amelia Taylor-Hochberg: Briefly describe your own pedagogical stance on architecture education. How would you characterize the programming at your architecture school?

Monica Ponce de Leon: The role of architectural education is to speculate about possible futures, and provide a critical stance towards the built environment, in ways that practice, because of all its constraints, can’t really do. In this way architectural education can anticipate or negate practice, and provide a counterpoint to what we consider practice to be.

At the college, we have strived for capitalizing on architecture’s interdisciplinary nature, as a way of providing a really open way of educating students. Here not everything goes, but also we don’t impose a single dogmatic point of view on the student body. We want students to look critically at the world, we want students to ask critical questions, but always from the architectural education can anticipate or negate practice, and provide a counterpointpoint of view of architecture, and always with an attitude that experimentation and reframing of conventions is at the forefront. It’s what an architect should and must do. The way that we do it is by constantly exposing students to different modes of thinking, within the discipline and outside the discipline so that they are forced to experiment. They are forced to do things differently. They’re forced to never take things for granted.

What kind of student do you think is drawn to Taubman and thrives here?

The kind of student that thrives here is the kind of student that does not want to follow party lines. The kind of student that wants to do something different from the norm, and is at the same time excited about the possibilities of architecture as a discipline, projected towards the future. The kind of student that thrives here is the kind of student that has the ambition to pursue their own architectural project.

How is Taubman’s programming doing that?

Our curriculum strives for opening up space for experimentation and critical thinking, as opposed to giving students a very specific methodology, or a very specific design… I don’t want to say style, but a very specific design criteria.

We have a great diversity in our faculty, we also have a great diversity of the tools that we put at the students’ disposal, and the curriculum doesn’t favor one tool over the other. We have, for example, in my mind one of the largest cohorts of history-theory faculty in the country: we have almost 10 faculty in the history-theory area. And yet, our curriculum does not revolve around history or theory. We’re very well known for our robotics fabrication lab and we’re very proud of it, but the curriculum doesn’t revolve around it. What is important is that the lab is a research, speculative space, for students and run by students.

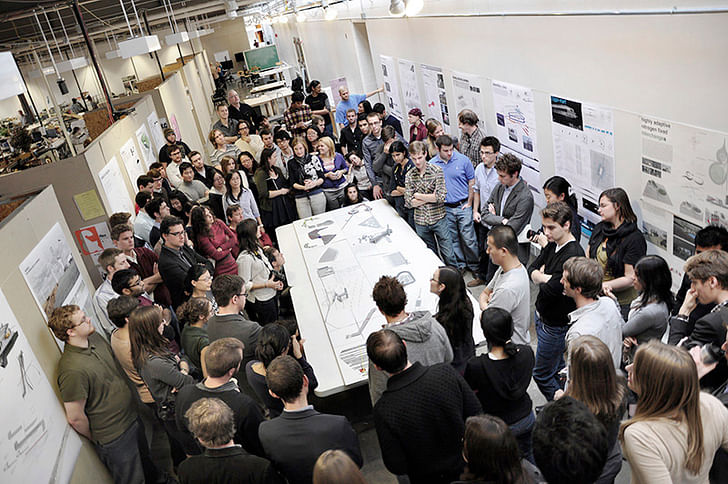

We nurture the diversity of our faculty, but encourage a conversation about the differences and expose our students to their multiple ways of thinking. You were at the Liberty Annex [last year] and I think that building is a great example. The Liberty Annex was created as an alternative to the conventional faculty office with four walls. The Annex is an old industrial building with open space, high ceilings and glass walls, in the edge of downtown Ann Arbor – which gives us visibility to the city as well. Most of our design faculty has their offices at the Annex, wall-less as part of an open plan. They also share unassigned open space for their research activities. At any given point in time, there are students working with faculty on all kinds of projects, experimenting with materials, searching new ways to draw urban conditions, or whatever interests them at the time. It’s a Think Tank for architecture and urban planning. As part of the Annex we also instituted a large exhibition space that is open to the public.The kind of student that thrives here is the kind of student that does not want to follow party lines.So as dean, my job has been one of promoting collaboration, individual exploration and structuring dialog. For instance, I instituted two research seed funding programs for faculty: “Research Through Making” and “Research on the City”. These are small grants that the faculty competes for every year (one in the fall and the other one in the winter). The grant applications are reviewed by scholars and practitioners from outside the college, who select 5 teams for each grant program per year. The faculty uses the funding to work with teams of students in the research projects. The faculty teams are usually interdisciplinary, and include faculty from other disciplines outside the college. The grant recipients present their research to the school at the end of the cycle and mount an exhibition of their work at the Annex. In this way, the entire school can participate on a conversation about the work, and their implications on larger themes in Architecture and Urbanism today. This conversation and its interdisciplinary nature has had an impact on our curriculum and on the way we have re-conceptualized studio.

These are all components of what we do here, but at the end of the day, architecture rules and architectural thinking rules. So the kind of student that thrives at Taubman is the one that’s very passionate about pursuing the discipline of architecture in an open way, instead of having the desire to belong to a school of thought, or a single mode of thinking about design.

If the intent then isn’t to push an agenda, or a specific style of architectural thought, but give students the materials and access to pursue their own interests in that fashion, how then do you balance that ethos while staying abreast of trends in the architecture industry? And how do you adapt those trends into real programming, with real attention to market forces?

What is important is that the lab is a research, speculative space, for students and run by students.Being a dean that is a practicing architect, I have come to understand that at the end of the day, most trends in practice seem to be coming from academia. I have seen things that we did at Harvard in the early ‘90s, later hitting practice and hitting the market and becoming trends and sometimes actually getting weakened and … sort of, debased. I think the direction of influence is in the other way, that what we do in academia impacts practice greatly. I don’t think of the school as one that’s trying to catch up with or follow trends; I see us as trying to operate outside of fashion and trying to operate outside of trends. Instead we search to understand the substance of the discipline, advance it, and hopefully find a space where we can experiment and do research that’s independent of the latest fad and the latest fashion.

So when six years ago, we set out to do the robotics digital fabrication lab, we were not setting out to do a trend for others to follow. We thought that a robotics lab would be an important component of how to understand the future of the discipline.

What do you see as the most difficult thing for incoming students?

Architecture today I believe is in a conundrum. On the one hand, design is everywhere, and attention to design is very much in the minds of the general public, and attention to the built environment, at least philosophically, is everywhere – issues of sustainability and public space are very much part of a global conversation. But in parallel to this explosion of interest in design, architecture at the end of the day is not valued as a form of expertise, or as having cultural agency.

So the challenge that I see for our students is that despite the power of architecture, and despite the long-standing high cultural value of the discipline, we’re operating in a cultural context that doesn’t necessarily recognize this. And that puts architecture at a very difficult moment globally. There are exceptions to this, there are countries that still see architecture as one of the significant contributors to the construction of culture, but this is not necessarily the norm.

What changes do you imagine you could make to the way architecture as a business is run, to give it more agency in that regard? Or alternatively, what problems with the current standard do you think need to be addressed, in order for architecture to have more cultural agency?

This is a great question about the state of practice in America today, and it has no simple answer. There have been certain critical moments in the history of architectural practice when we’ve made, as a discipline, strategic mistakes. In the second half of the 20th century, architecture progressively retreated from controlling building, and gave up certain aspects of the process to other industries. Today, you have construction managers, client representatives and a whole industry of building experts filling the gap where architecture left off. This has put other disciplines in the driver’s seat, and gave them more control over what it is that we do. One of my fascinations with digital fabrication is the elimination of “the middle man”. The idea that you can have the architect control the means and methods of construction, and actually drive the processes of building in ways that we were not driving it in the 90s, when I started working with digital fabrication. at the end of the day, most trends in practice seem to be coming from academia.The dependence on multiple industries and experts for the construction of buildings has exploded to such a degree that I don’t think it’s retrievable. In other words, I don’t think the architect is ever going to “regain control” over the means and methods of construction. So we need to learn to operate within that system, change it, and find ways to exert our power that are different from the way that we did that in the past.

But there are more recent trends that I do think can be addressed. I believe that with the 2008 recession, architecture panicked, and that as result, the architectural conversation has been dominated by two topics: there are those that argue that architecture can save the world – architecture as superhero. The work coming out of these practices has tended to be amorphous and ironically of very little societal consequence. In turn, there are those who argue that technology is going to make architecture relevant – save architecture. The work coming out of this camp is what I call superformal, with multiple variations on forms that may not have been very good to begin with. Both of these topics are distractions that take us away from the true impact that architecture has on culture and society.

Architecture as superhero is problematic for several reasons. As citizens, most of us would agree that we would want a better world. But I think as architects, we should be a bit more modest. To pretend that architecture can fix the environment, or that architecture is going to solve social disparity, actually masquerades the socio-political structures that cause and sustain these problems – and in turn helps perpetuate them. We should all of course follow best environmental practices in the design of buildings, and these are all valid subjects of architectural research inquiry. But we must also acknowledge that this is not enough, and that the only way to truly address the disastrous state of the environment, or the extreme social inequity of our times, is legislation. These are not design problems, but political ones.

On the other hand, placing technology at the center of our discipline is problematic because it relinquishes aspects of the discipline that I consider essential. Architecture is one of the few disciplines at the intersection of the humanities, the arts and the sciences. Reducing architecture to technological mastery gives away our true complexity – while ironically making form seemingly more complex.

there are countries that still see architecture as one of the significant contributors to the construction of culture, but this is not necessarily the norm.I think that the panic came from fear that architecture might not be culturally relevant. I believe that we are coming to the end of the era of panic and there are lessons to discern form these recent distractions. At the end of the day, form is what we do; form is our business. We are shape-makers and form-makers. We shape space. That’s what we do that’s different from other disciplines. And by the same token, that’s actually what gives us cultural agency in the world. This is how we effect culture. I see a new conversation emerging that acknowledges that the discipline of architecture has a robust history and a history that is very much at the heart of the construction of culture.

Regarding that, what is Taubman’s relationship with the local government?

We were speaking before about how we are operating in a cultural moment where architecture is not valued by society as a cultural agent. This is not surprising, given the fact that the arts have been progressively eliminated from K-12 education. It is also not surprising when you think about the fact that practicing architects do not reflect the diversity of our country. To address both these issues in concert, we approached the Detroit Public School System to develop an architecture program for high school students. The program was just launched this January in collaboration with 5 high schools. We expect it to grow to seven high schools with a total of about 100 students per year. Our motivation is to expose high school students to the discipline of architecture, in ways that otherwise they would not be exposed. Students will be taking studio courses in architecture for high school credit. It’s not an extra-curricular activity; it’s actually embedded within their curriculum. Because we’re working with seven very different schools in the Detroit public school system, we’re also targeting students with diverse backgrounds and ethnicities. With funded by the Mellon foundation, the studios are taught by teaching fellows – recent graduates from professional degree programs across the country selected on a competitive basis.

I know Taubman doesn’t have departments as such, but within the University at large, how are collaborations between the architecture school and others orchestrated? What’s the priority?

One of the reasons I came to Michigan is because I was extremely interested in developing a different curriculum for architecture school, where the architecture studio is the center of an expanded curriculum that capitalizes on collaboration with other disciplines. We have collaborations with engineering, with the school of natural resources, with music, art and design, public policy, public health and the humanities. The intent is to have architecture be the center of a conversation about a myriad of topics that might not seem to be design-centric. I don’t think the architect is ever going to “regain control” over the means and methods of construction.I’ll give you one of my favorite examples, which may sound unusual. We like pairing up studios with either lectures, lecture-courses or seminars in other topics, so when a professor teaches a studio, he or she may actually decide to pair up with a professor in history, or in engineering, or in art and design, etc. The students in the studio are then taking that lecture course, that seminar. So for instance, we had a seminar taught by an architectural historian, who also has an appointment in art history, who decided to explore the impact that tools had in the design of buildings during the Baroque and in the thinking of the period. That seminar course was taught in parallel and in association with a studio that was looking at the impact of digital fabrication in design today. So the students were looking at a historical precedent, as analogous to the research project in studio. The students traveled with the two faculty members to Rome, to look at the buildings first hand – as a preamble, as a context for their larger project.

The other program that we have, that is parallel to this notion of pairing up studios with other courses, is a program called “Expert in Studio”, where we bring scholars, designers or practitioners to the College for a week or few days to conduct workshops. Sometimes it’s tied to a specific studio, sometimes it’s available to the school at large. We’ve had designers but also faculty from allied disciplines, like structures, history/theory, urban planning or urban design, work with architecture students on a particular topic. That’s another way in which we attempt to make studio the center of architectural education, but integrate it with other practices.

How do you prepare students for being employed in the architecture world after graduation?

What I think is different about us is that we have purposefully taken out of the curriculum courses that are specifically geared towards skill-building, in order to open up more space within the curriculum for critical thinking. What we have done instead, is that we have a myriad of extra-curricular offerings – workshops, web tutorials – that allow the students to build their skills, and to build them strategically in relation to their own interest, but also in relation to courses. Our goal is to ensure that studio time is used as a way of critically looking at the discipline and the world.

How important is it for a dean to also be a practicing architect?

Nobody has ever asked me this question… Perhaps naively, I do not see as much of a divide between practice and academia, as others claim there is. The studio model is a great preparation for practice – the kinds of things that students undergo in studio is not dissimilar than the kinds of things they’re going to encounter when working in an office or as practitioners.

For me it’s been important to get my hands dirty and practice, even though sometimes it can be difficult, painful, messy, boring. I’m interested in the kind of academic research that I have done actually having an impact outside of the boundaries of the academy. Most of my career has been in understanding how digital fabrication can affect the way we conceive buildings and spaces. If you only research this within the safe confines of your lab, then I think you leave out the important pressures that this messiness that I was describing before brings to the project. Reducing architecture to technological mastery gives away our true complexity – while ironically making form seemingly more complex.I was doing research at Harvard and then Georgia Tech in digital technology, and at the same time we were commissioned by Rhode Island School of Design when I was principal at Office dA to do the library at RISD… And that kind of tension between what I was doing in the lab and the real-time constraints of a project that needed to be delivered with the complexities of schedule, materiality, budget, etc., that kind of exchange is what I enjoy, it’s what I find productive, what gives me pleasure. So for me, doing both is part of the same system, they’re not exclusive.

In terms of marketing and branding, how do you communicate the school’s personality to not just prospective students, but a general public, the city, donors, faculty, etc.? How do you manage the school’s personality in the eye of the public?

To be honest with you, I hate branding. I find it superficial and debasing. For us it has been more important to search for multiple ways to open up the discipline and give students and faculty the tools and the space to grow – that has been more important than to provide a single image for the school, a specific identity for the school, that can then be marketed and sold and consumed. And in that regard, my attitude has been to provide support to diverse interests and ideas. Research Through Making, and Research on the City are two programs that I think are symptomatic of the ethos of the school, that is very open and to devise a platform for everyone to pursue their own interests, as opposed to being very prescriptive and only endorsing what I call the “single party line”. By the same token, at Michigan you’re not going to be working in isolation. You’re going to be part of a conversation. So we have not To be honest with you, I hate branding. I find it superficial and debasing.pursued that which is going to differentiate us from this or that school. Instead we’ve operated with the intent of making architecture stronger than it is today. For us it’s a conscious decision of not preselecting from the top-down a single mode of thinking, but instead exploring and providing a heterogeneous cohort of ideas that students will then be exposed to and make their own choices.

When you leave Michigan, what are you most hoping to have accomplished or changed?

I’ll give you a side-story. The Mellon Foundation organized a retreat with deans of architecture schools. They wanted to see if we could help them figure out how the design studio could inform the humanities. Their premise was, the humanities are under siege, and in an era where the value of the humanities are being questioned by the public, can the humanities learn from studio instruction as a way of reinvigorating them. That led to a whole cohort of Mellon grants being awarded to architecture schools, us included, and now we’re collaborating with LS&A, where we’re pairing up studio with humanities courses. We’re pairing up studio faculty with scholars looking at the contemporary city. We’re studying Mexico City, Rio, and Detroit, and understanding how the relationship between design and humanities scholarship can transform our way of thinking about these cities for the future. Design is very much at the center of the conversation, as opposed to being one in a menu, or as “part of the conversation”. What I hope to achieve as Dean is to restructure architectural education: to restructure research in an architecture school, where design is understood as an art form as well as a form or expertise, and where studio is at the center of what we do as architects.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

10 Comments

This editorial is such a clear, realistic insight into the inner workings of Taubman College and the impact that Dean Ponce de Leon has had on the program. There is no doubt that Dean Ponce de Leon is the ambitious force behind the successful shaping of the program, which has resulted in the much deserved plaudits from the academic and professional world. As a student in the M.Arch program, I couldn't be more happy with my experience thus far. As the Dean says "Here not everything goes, but also we don’t impose a single dogmatic point of view on the student body". This line of thinking is certainly permeated throughout the courses offered at Taubman, I have had such a diverse experience and that is something that you won't find in the majority of M.Arch programs across the country.

My friend Dr. Behn Samareh (left) just bought a robot for his shop. I am really looking forward to seeing what he does with it.

Seems like she is running a very sober program addressing many things in and around architecture gradually and realistically. I think ultimately women are more prolific, collaborative and earthy than men who put themselves at the center stage, wanting to be heroic, fearless and adventurist directors.

The collective energy comes out from that big studio space must render the space heaters unnecessary.. Sea of architecture...

Monica's focus on facilitating different modes of thinking and interdiciplinary experimentation was definately why I chose to come to Tuabman College. As someone with a background in something other than architecture, it is great that the school embraces nonconventional ideas and methods of design.

great comments from Ponce de Leon. I'd only hear her name before. Definitely a fan, now.

What a fantastic interview. The school has so much energy! Check out her own work at her website. She is incredible. Beauty is her mantra.

Beautiful object buildings, maybe. Beautiful places, not.

Thayer - You obviously haven't done your homework or spent any time in one of Monica's buildings. Take a timeout and visit the Helios House in California, the Macallen Building or Banq Restaurant in Boston and then tell me she doesn't create beautiful places.

...or you can just continue to troll everyone on Archinect while not contributing any original content of your own, your choice.

Sorry to disappoint you Harold. Like I said, some of the buildings look nice, but they are not very good urban buildings. Should the architecture world be segregated into those who don't care about good urbanism and object buildings? I don't think they are mutually exclusive.

She says,,,"– issues of sustainability and public space are very much part of a global conversation" Well, I'm trying to have that conversation rather than spitting out the words without any follow through.

Then again she says..." we must also acknowledge that this is not enough, and that the only way to truly address the disastrous state of the environment, or the extreme social inequity of our times, is legislation. These are not design problems, but political ones."

Let's have a conversation about what then, politics?

What a fantastic interview and beautiful object buildings!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.