A few weeks ago we reported that the USPTO granted trademark protection to Apple for aspects of its retail store designs (Reg. No. 4277914 & 4277913).

Image above, Reg. No. 4277913 (claiming color)

Image below, Reg. No. 4277914 (not claiming color)

While most architectural works don’t have the notoriety and consumer association necessary to obtain federal trademark protection, architects have long relied on copyright and design patents to protect their creations. Since 1990 when “architectural works” were first incorporated into our federal copyright regime, much has been written about its use and impact. Yet few architects have stopped to consider the role of design patents.

But design patents aren’t new. Architects in the US have relied on them for over a century to protect new, original, and ornamental designs for any article of manufacture. For example, Frank Lloyd Wright was granted numerous design patents on everything from chairs to desk and home designs.

Design Patent No. D114204 (granted April 11, 1939)

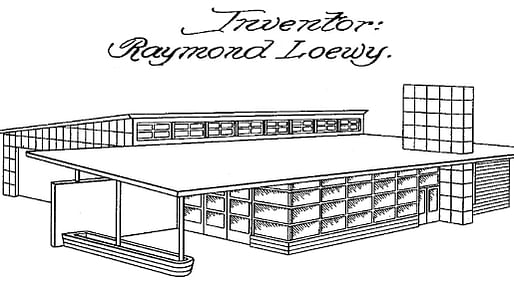

Similarly, Raymond Loewy was granted tons of design patents on things like automobiles, electric shavers, railway cars, and even building designs too.

Design Patent No. D149076 (granted March 23, 1948)

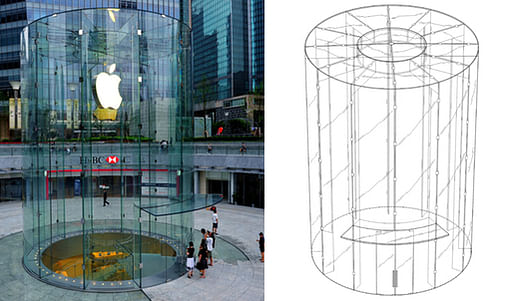

And for modern examples, you don’t have to look any further than Apple. They have not only trademarked aspects of their store layout, but they were granted design patents for their cylindrical glass storefront and staircase designs too.

Shanghai Storefront (Flickr) & Design Patent No. D656240 (granted March 20, 2012)

London Retail Store (Flickr) & Design Patent No. D478999 (granted August 26, 2003)

Despite their widespread use, most architects know remarkably little about the basics of design law. In an effort to help educate designers and to better understand how people’s backgrounds effect the application of design laws, the Max Planck Institute could use your help with a new study that it is conducting. The project revolves around a series of brief hypothetical juror scenarios where you are asked to apply one of these legal standards. Don’t worry, they’re quick and easy to follow. At the end of the survey, they email you the results so that you can see how you compared to the actual court outcomes, and they even provide you with a lot resources to learn more about other important aspects of design law (e.g., what sorts of things can be patented and what does it mean to infringe another protected design).

Regardless of your feelings towards intellectual property protection in this area, you should find the study fun and helpful. Most importantly, all of the money generated by the study is being donated to design charities.

There are only a few days left.

This article was submitted by the Max Planck Institute, as part of a project intended to provide insight into how people's backgrounds affect the application of creativity requirements in design law.

8 Comments

I really want to know what Apple paid the architects (BCJ?) to give up all of the copyright for these.

I took the survey. I feel I'm a bit cynical about whether design can give a person a sense of social status - it definitely shouldn't but, but I guess it does.

Steve, I think the architects BCJ must have gotten paid Zero dollars. Apple and their attorneys are notorious in writing contracts, and must have surely put in some clause stating that they own all the rights...

I think BCJ is a smart and long-running firm with plenty of experience in contract law.

This is a really interesting topic -- I'm looking forward to taking the survey.

The patent for the staircase is pretty funny. Where is the innovation here? All I see are steps (with a code-mandated height, landing, etc., I presume) and a handrail, in glass, using what seem to be standard connectors (anyway not shown in detail). There are no overt claims about specific properties of the design in the patent application, so I don't see how they would be able to use this patent to chase anybody on anything.

Which is probably good news. The most important information on patents in architecture, anyway, would be how they have play out in case law. Sounds like the survey will talk about this...

You did notice that it is a clear span glass tread right? BCJ did that something like a decade ago and it was pretty innovative, and still is to some degree as it isn't easy to do. I just find it really interesting that BCJ has such a long relationship with Apple which has been so mutually beneficial, and yet there is zero mention of them in any of the copyright information. Considering that architects retain copyright to their designs unless they sign them over, I just found it interesting to hear all of this discussed as if Apple designed everything.

Thanks for pointing that out, Steve. I did not notice. So the real innovation is in the structure of the tread, I suppose, although I see no indication of scale, nor any dimensions in the patent... I'm still mystified about what specific claims are being made. As for BCJ, I suppose they sold or granted the rights to this design to Apple. Or maybe Steve Jobs really did design it!

Patents on architecture seem like bad news for the profession overall. Motivations for innovation don't work the same as in product design, for instance, and the impact of a patent infringement would seem harder to cope with (destroy or alter a building that is already occupied). I happen to be currently involved in a project (in its infancy) to promote an open-source methodology for architectural details (i.e. share them for free) -- I will try to post some stuff about that once we get it off the ground. I would certainly like to hear the thoughts of the archinect community.

BTW the survey does not talk about architecture directly, for anyone still thinking of taking it. It's all products -- but it is fairly interesting.

It should be mentioned, I suppose, that the point of patents is actually to share the information on how things are made for free, and just to lock in a delay on that sharing so that the inventor can benefit first. I don't think the drawings in this Apple stair patent contain any of the intelligence behind that design (again, they are not explaining the structural and/or material ingenuity), so they aren't really sharing much. By the same token, if I repeat just the form of what's in the patent (using a more conventional material), then I've built a pretty generic staircase and it would seem impossible for Apple to pursue me. So, more and more, this patent seems like an exercise in futility. Perhaps it's just a natural step for Apple, as a product company, to patent anything it is involved with, regardless of the merits.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.