For an architect, in the instant that he has undivided attention of a patron with the power to realize his designs, literally nothing else matters; not a fire alarm, not even an earthquake; there is nothing else to talk about but architecture.

-Dejan Sudjic, The Edifice Complex

The fully developed ability to say No is also the only valid background for Yes, and only through both does real freedom [begin] to take form.

-Peter Sloterdijk, Critique of Cynical Reason

City

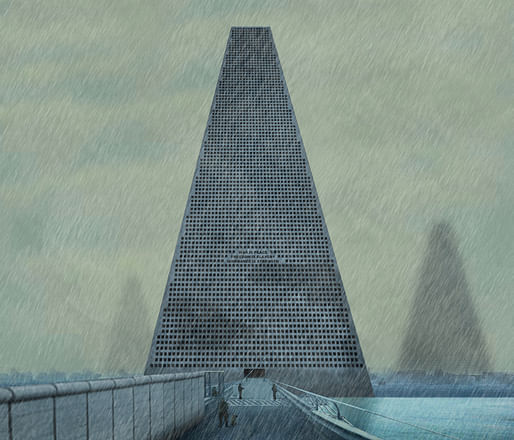

Four towers rise above the city like muscular trunks in a grass field. Their scale obliterates any possible question about the intentionality of their disproportionate size. The exaggerated disparity between them and the urban fabric could not have been accidental. The towers were unquestionably built to be the main focus, the sole object of attention. They are by lengths the most important buildings in the city. The towers deliver an explicit message of datum and order. Visible from any point in the city, the towers exploit the potential of architecture as iconography. They are archetypes of power.

These concrete monoliths, three with facades perforated by square windows, the other one solid like a hermetic bastion, soar until reaching six hundred meters of height. Each of the towers represents one of the four governmental ministries: love, truth, peace, and plenty.

Competition

The towers were not always there. For them to be completed an architect had to be chosen. The ministries joined to hold an invited competition for one architect to design their four headquarters. The contest called for a “series of monumental structures that through their form, and their use of image, outstandingly portray the values of society. Buildings capable of communicating the permanence and importance of the institutions they host.”

A group of famous architects –the best in the world—was invited to submit a project. Without hesitation (how to resist such an important competition?) each one of the designers proposed a series of buildings. Although varying in form, the proposals recurred to a similar strategy: they were all architectural icons. Some of the projects were typical signature trademarks, buildings that responded more to a consistent development of the architect’s formal language than to the specificity of the competition’s program. Other proposals took a more generic approach presenting buildings with predictable aesthetics, market oriented architecture. One of the submissions stood out because of its obvious simplicity. Of all the projects it was the only one with four identical towers, consolidating with a single form the competition subtext to make the ministries appear like omnipresent manifestations of power.

Following the submission deadline, all the projects were displayed through a series of exquisitely arranged public exhibitions containing conceptual plans, detailed specifications, explanatory diagrams and all the physical models. Newspapers, magazines, TV shows, and radio programs flooded the public with newsflashes and continuous updates about the projects and the architects who designed them.

Celebration

Bursting the bubble of suspense after some weeks the winner was announced. Following the award ceremony the Almanac of Contemporary Architecture, the most prestigious architectural publication, devoted twenty pages to the master architect under the title “Project 1984” featuring his watercolors, ink drawings, pencil sketches and some verses of poetry written in his sketchbook.

One of the pictures of the Almanac displayed a group of figures, between them members of the respective ministries, representatives of sponsor corporations, the architect, and some expert advisors looming perversely over an architectural model. The scaled construction of the master plan included a reduced version of the city and from four different points of the almost homogeneous composition of the low rise buildings on the surface, stood four behemoth towers of slender pyramidal shape and truncated tops.

Strategically collocated at legible height, each one of the towers was engraved in the façade with the slogan of the ministries in bold, capital letters: WAR IS PEACE, FREEDOM IS SLAVERY, IGNORANCE IS STRENGHT.

Critical

Needles to offer the remaining plot of a story of already known resolution; it must be made clear that this story does not aim to defend the architect for either the cultivation of his political naiveté or his opportunistic ambitions.

A mixture between architectural fairytale and social nightmare this story imagines a preceding scenario for George Orwell’s political masterpiece 1984 (1948), exploring that perversely “ideal” moment on an architect’s career when he finally has the opportunity to bridge the gap to fame and immortality and construct the most important buildings in the city. That paradoxical instant when the edifice of humanity comes crumbling down hammered by the same forces that make the architectural chef d’oeuvre go up in the first place.

Like in 1984 architecture has been a fervent accomplice to some of the most atrocious political regimes in recent memory. In the 20th century alone, architecture went from Nazi, to fascist, to communist, to capitalist, piling up a staggering amount of icons that oscillate from extreme historicist kitsch to extreme refined modernism.

In fact, a closer inspection of the historical relationship between architecture and politics reveals that Iofan, Speer, and Terragni were not rare exceptions of a beautiful profession in search for tools of a better quality of life, but the blunt symptoms of a discipline with the dangerous aim to achieve its grandiloquent delirium at all cost.

How can a profession whose education and practice –based on selling projects through visual manipulation and redundant, subjective, apolitical rhetoric— maintain a critical stance when the conditions in the real world are completely fueled by politics? Is architecture the ultimate ideological anesthetic?

Cynical

In this fictional prelude to 1984 it is not coincidental that the architects were used as instruments for propaganda and political control. With cynicism becoming systematically embedded on the architect’s intellectual repertoire since his days in the academia the mantra that claims “architecture is architecture, and therefore should be judged as architecture” has been drawing architecture as an apolitical tool to the service of political charged ends.

In the real world, unless we are ready to challenge the way we teach, think and practice architecture, and consciously discover what makes us be tempted by whatever awfully detrimental project is being schemed by technocrats, CEOs and politicians, and finally become prepared to substitute the prevalent unconscious cynicism of the profession with a Sloterdijkean kynicism (the one that resists, provokes and subverts), we may not only continue being faithful contributors to some of the most dangerous regimes in the world, but we may even become the master architects of Project 1984.

--

Project 1984 has been published in Zawia #00, Cairo and in What About It? Part 2, Beijing

WAI Architecture Think Tank is a Workshop for Architecture Intelligentsia founded in Brussels in 2008 by Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz Garcia. Currently based in Beijing, WAI focuses on the understanding and execution of architecture through a panoramic approach, from theoretical texts, to narrative architectures, to urban and architectural experiments. WAI asks What About It?

1 Comment

I am so glad to see a discussion of cynicism and kynicism on here. It would be good to see a compilation or overview of how various well-known architects feel about this issue.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.