Last week, our editorial team had some fun with the metaverse. While light-hearted in nature, our April Fools article was nonetheless inspired by the serious interest shown by our community, the architecture world, and society at-large in the metaverse and how architecture and design intersect with virtual space.

Now, a new article by UCL researchers Luke Pearson and Sandra Youkhana puts forward the thesis that the metaverse doesn’t appear as disruptive or radical as the underlying technologies it is often associated with, be it blockchains, cryptocurrencies, or NFTs.

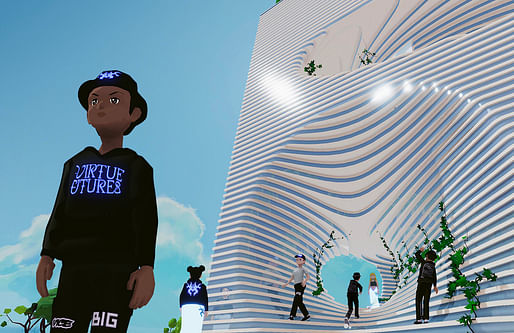

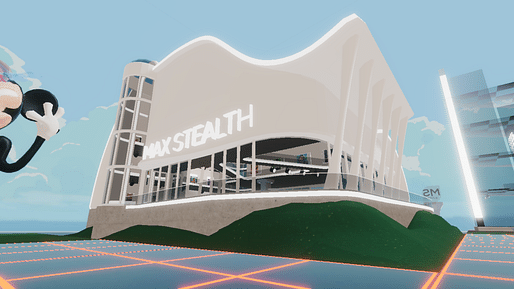

Instead, the team argue that the architecture and urbanism of the metaverse appears to follow real-world principles of design and construction, despite the freedom given by virtual space to transcend these principles.

“People have always imagined cyberspace to look like a version of real urban space,” say Pearson and Youkhana. They cite the original design for the metaverse created by sci-fi author Neal Stevenson in 1992, where a “grand boulevard wrapped around the globe, but was nonetheless presented as a typical urban thoroughfare, lined with buildings and electric signs.”

Thirty years later, the same adherence is visible in Mark Zuckerberg’s vision for the metaverse, where promotional adverts show users “walking through food halls or seated in train dining cars, all designed to look like their real-world counterparts, but rendered in a simplistic graphic style, like a children’s TV show,” complete with “practical yet unnecessary design elements including streetlights, plug sockets, and window frames.”

To explain this phenomenon of “ordinariness” in the metaverse, the team argues that familiar architectural elements are placed in virtual worlds in order to establish familiarity with the user, despite the potential for virtual reality to defy laws which underpin physical architecture, from gravity to building codes.

This attempt at enhancing the familiar is not confined to virtual reality, the team says, but has also manifested in the design of physical environments too. They cite Disneyland and Las Vegas as two examples where a surreal, stimulating, but familiar “architecture of reassurance” has been created in these environments to create a landscape which is “both new and comfortably familiar" despite its excess and extravagance.

While transferring this familiarity to the metaverse may create feedback loops between physical and virtual words, exposing how both designers and citizens understand and interact with their surroundings, the team also emphasizes the need for the metaverse to go further.

“Virtual spaces need to be convenient for people to access and engaging enough for them to return to,” they conclude. “They also need to harness and extend what makes them different from physical spaces. Simply transplanting real-world logics of property development and trading into the metaverse might recreate the social and economic stratification we find in real-world cities, which undermines the metaverse’s emancipatory potential.”

The full article is available to read here.

4 Comments

Great stuff - good to see a critical look into why these things look the way they are. I guess the limits of architects' technical skills also apply to the extant of their imagination? Perhaps game designers and VFX artists are better trained to craft these virtual worlds.

This is very true that futuristic designs and constructs strive for familiarity or they still are struggling to exploit the full potentials of imagined space and time. When Star Trek, the Next Generation was aired, one aspect that came across clearly was how the command structure on the Starship just echoed the command structure that we have in our armed services now and Starship was placed in the year 2400!

The question about simultaneous universes with overlapping intentions can be resolved by recognizing you cannot be in two places at once when you are not anywhere at all. Thank you. Mr. Lennon.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.