The 25th issue of MONU “Independent Urbanism” provides a platform to unveil the multitude of decisions that had to be made by countries after becoming independent - and more specifically the cities within these countries.

by Amy Tibbels

— http://www.monu-magazine.com/news.htm

In 2010 we became familiar with instagram and along with it a new way to represent ourselves. In the same year, the Republic of Macedonia’s capital city Skopje decided to completely cover itself with false neo-classical facades, embodied with hundred year old representation. The 25th issue of MONU “Independent Urbanism” provides a platform to unveil the multitude of decisions that had to be made by countries after becoming independent- and more specifically the cities within these countries. The magazine’s photo essays have an indispensable heaviness within this particular issue of MONU, in it’s twelve years it has never featured as many as three. Of this we can be appreciative in largest part because these intimate images bring authenticity to some inconceivable realities. But further, what I find integral to each of these photo essays is a nostalgia, which becomes a binding agent of most articles as if being the authors’ communal grand answer to the question; what happened to these cities after independence? In their transformations cities are either courteously welcoming or sedating this nostalgia. What I find to be left in many of these cities is something so far not clearly defined, it seems to hold many pseudonyms; the Other, no-mans land, third space, space of otherness or non-place.

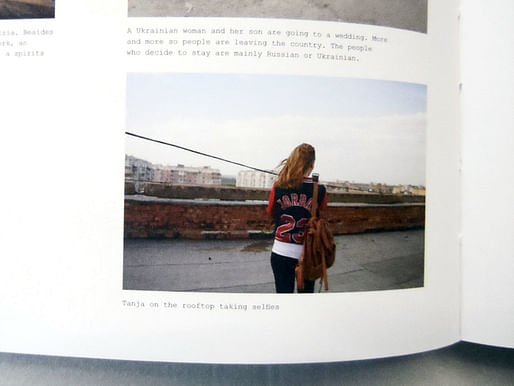

The magazine begins and ends with Julia Autz’ photo essay Transnistria. Our first subject is the cover-girl, 14 year old Xuishu who wants to leave her home of Transnistria, a “self-proclaimed state...not recognized by anybody – not even by Russia”. Xuishu embodies a longing to emigrate that much of the city’s youth share. Resistance and longing are framed side by side in the photo essay showing both; veterans of soviet time in melancholic nostalgia “holding an old soviet Lenin flag high in the air”, and beacons of Transnistria’s youth such as Xuishu, wanting more. Here also, Autz exposes the county’s national confusion, amid youth desperate for something else are markets filled with Ukrainian-worldwide consumables and celebrations of Soviet victory day, which is still the most important holiday in Transnistria. Russian and Ukrainian people are the larger groups deciding to stay in Transnistria and so; adopted nostalgia and uncertainty of what to reminiscence is clouding the chance for this region, especially its youth, to have a clear identity. Like in Transnistria, nearby Chisinau’s youth also find themselves enveloped in the city’s “unlikely point of resistance” as part of an in-between state, “pressed between Romanian and Ukrainian lands” explained by Sandra Parvu in her article. Parvu perfectly compliments the photo essay by referencing artist Ghenadie Popescu who inconveniently placed himself in a tiny thermal buffer zone between rooms to liken the spatial characteristic to that of Moldova between nations, suffering a persistent afterlife of the Soviet rule. Parvu explains this to say that Moldova “cools the heated conflicts between the European Union and Russia by disregarding its sovereignty and changing its boundaries as they please”. This same dual nostalgia is also discussed earlier in Pravus’s article where she describes a resulting “parallel geography”. Taxi drivers navigate the city of Chisinau with an atlas of its streets possessing both Soviet names in Cyrillic, and post-Soviet names in the Roman alphabet. Despite old names being connected to the Soviet nomenklatura they are still very commonly used, and this “parallel geography” is a clear result of the city’s uncertain nostalgia. These two articles were well placed together at the magazine’s end, revealing cities of not one or the other strategy but within a struggle trying to welcome both.

While Chisinau and most other Moldovan cities have lacked power to make big decisive transformations, many cities in other newly independent countries have found themselves in the contrary situation, in anticipation for considerable change. This is condensed well in Gruia Badescu’s statement that many countries with new independence such as those of post-Yugoslavian countries, have developed a heritage focus on one of two things; “EU sanctioned cosmopolitanism or of highlighting one’s nation and silencing the minority (or former majority) presences”, in either case avoiding nostalgia. A recent example is found in the magazines first article, where Jasna Mariotti identifies the Republic of Macedonia’s largest city; Skopje. After an earthquake in 1963, the city embraced its chance to modernize. Beginning in 2010, the city made a second decision to revamp, but this time a premeditated “amnesia was omnipresent”, filling its once modern city centre with buildings of a style considered “baroque [and neoclassical], a pseudo interpretation of a historical style, and a striking contrast to the modernist and novel architecture that dominated the city centre”. To complement these new icons of grandeur, “faux facades” have been clipped on and statues scattered over the city like jewelry as if it was “dressed up in nostalgic recall”. The 2010 development sprang quickly into realization by 2014, and I find inconceivable that such a project shares the same year of foundation as instagram or the ipad. Apart from its displacement, it was an arguably improper solution to sedate and forget the slow melancholic transition from independence it had suffered. In South Africa’s Johannesburg, Claire Lubell claims that money has replaced race and the city is, similarly to Skopje, sedated in this case by an “idealized world of excess focused on play, fantasy and consumption”. These new spaces with such superficial cohesion aim to not only avoid the apartheid but also to “reinvent it, a process for which Johannesburg is notorious”. I am pleased to see a vary in the magazine’s geographical examples such as this, because here I see Johannesburg’s consumption sitting similarly to Transnistria’s market, however in this case with much greater antipathy for nostalgia.

In his photo essay Victory Park, Arnis Balcus presents “the Other”, other sex or ethnicity. Also, his play with a duality of inside and outside is a framing for the duality of political transparency in Latvia’s most influential city; Riga. The collective and personal both share a discomfort and stagnation, nostalgia for the past like many other cities mentioned, and slow uncertainty about the future. This is terribly polar to the image that Riga city architect Gvido Princis courteously paints in the magazine’s second interview, where he notably forgoes the opportunity to discuss Riga’s clearly evident issues of divide in ethnicity as mentioned by Balcus. The divide began with independence, but was fostered in the country’s lengths taken for NATO membership. For example; the 2002 law requiring parliamentary candidates to be Latvian speakers, and the 2004 Russian language restriction in school institutions, which have strongly maligned Russian citizens in many ways to become and remain “the Other”. Balcus is not alone in his use of the other. The term was often mentioned in the magazine, under different flavours of uncertain urban concepts, firstly being the no-man’s land. This war-linked term was mentioned by Milda Paceviciute and Burak Pak when describing North Ireland’s conflict in Belfast’s “derelict lands”. They translate the term into more comfortably philosophical or urban inspired by philosophical terms “third space” and “space of otherness”. The overuse of this terminology in the response of authors reveals a very large scale confusion and lack of identity, a common and still apparent struggle for countries in new states of independence. However, in most mentions these terms have been roughly transplanted directly from examples fashioned by urbanists in the mid-90’s. The most applicable of these is Marc Auge’s. Within his 1995 analysis of supermodentity Auge’s term of “non-place” is described as an area not defined as relational, historical or concerned with identity.

Two decades later I think Marc Auge’s term could be resettled here to understand this widespread confusion and waiting that new countries are stuck with, as some authors in this issue have begun. Here it is possible to collect these experiences that contribute to ambiguous independent identities, from post-emigration emptiness to Soviet nostalgia. This could also be a lens for us to imagine how the youth of most cities inside this magazine view their cities, as a non-place disconnected to history and identity. It should be clear to see why Xuishu and her many similarities dream of leaving. I also consider that this youth will search for identity externally, predominantly through technology. This is something we all do, science and technology has always been a contributor to identity. However, if technology and globalization are to become a resolve for lack of other sense of self, we need to be careful in the way we rely on elements of our world that we have created. This is especially vital for people like Xuishu within a place where people are vulnerable under these national uncertainties. A person that perfectly assembles this idea is another of Autz’ subjects; Tanja from Transnistria. “Tanja on the rooftop taking selfies”. Here we see something not too unfamiliar, a young girl taking a selfie facing the city’s skyline. But what she holds in her hand has capabilities to connect Tanja, especially for a youth in search for something different the scale of technology’s potential is huge. This is something with consequences still to be seen, in fact it should be stressed that answers to most obstacles within this magazine still remain to be seen. I feel that in an optimistic frame this issue of MONU is similar to Montenegro’s pavilion in Venice, one of the magazine’s articles angled towards a possible success. Bart Lootsma explains that their open project was taken to Venice with an aim to “get attention for it in order to put the issue on the public agenda” but what was crucial was to also “give the project a different authority in Montenegro”, this was attempted through locally held debates and participation. As a parallel, the magazine also draws attention, stressing these current and vulnerable states and the best outcome would be an eagerness among readers, wanting to see what happens next for these independent countries and their cities. I think the magazine is right in claiming it “functions as a platform for the exchange of ideas and thus constitutes a collective intelligence on urbanism”. But what I think needs to follow this issue, and I hope to see, is a different authority applied to the difficulties in each of the cities mentioned, just as is happening in Montenegro.

Amy Tibbels is an architecture student from the University of Technology Sydney, in Australia. She spent time studying in Denmark at Arkitektskolen Aarhus and is currently on an internship in Rotterdam.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.