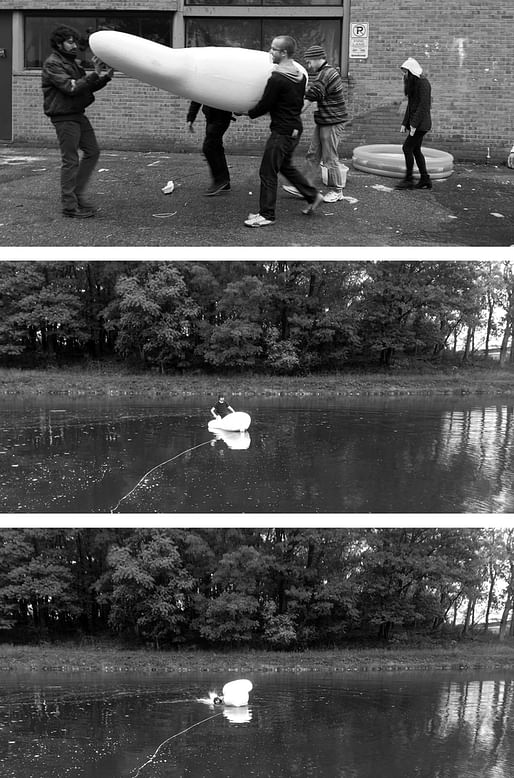

Last Wednesday afternoon, traffic briefly stopped at the main entrance to the University of Michigan’s North Campus as 12 of us hauled a stark white blob the size of a jet ski up hills and across intersections. Curious and confused onlookers watched us as we carried what must have seemed like an unidentifiable object towards the small pond located behind the School of Music. Despite the cold and the rain, the workshop group prepared the form for its maiden voyage, and watched as its water ballast was filled, allowing the foam blob to slowly position itself into a floating megalith. Throughout this trek the workshop’s leader, MIT Assistant Professor Brandon Clifford, walked alongside answering questions. For Brandon, this procession towards the water was not just a familiar aspect of his research in megalithic constructions, but instead an essential element of the history and significance of volumetric design.

Two days earlier, Brandon began his ACADIA workshop session by telling the myth of the Moai on the Pacific island of Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island), who were said to have walked themselves into their final resting spots. According to Clifford, it wasn’t until 2012 that archaeologists determined these stone figures had indeed walked across the island, as their sculptors ceremonially rocked them with ropes from side to side. While this discovery answered questions that had plagued archaeologists since the Moai’s discovery in 1722, Brandon explained how this recent discovery suggests that at some point in time knowledge of volumetric design and construction strategies had been lost. By creating megaliths, Clifford hopes to not only draw attention to the preference given to the surface (as opposed to volume) in digital design environments, but also to reintroduce physics-based modeling practices into the architectural vocabulary.

As a student in the Masters of Science in Architectural Research and Design (MS) program here at the University of Michigan, the opportunity to participate in this year’s ACADIA Conference and Workshops felt like packing an entire course into a week. During the three-day workshop, I was instructed to download a series of unfamiliar Grasshopper and Rhino plug-ins named after equally uncommon animals, and subsequently given a crash-course in the operation and significance of what was obviously a highly-tuned Grasshopper script. Participating in the workshop meant that not only did I get to add a highly crafted tool into my library, but I also got to take a break from the semester and become temporarily immersed in a mode of thinking which was entirely different from the coursework I was just growing accustom to. Given that the University of Michigan's MS in Architectural Research and Design is only one year long, the ACADIA workshops provided the opportunity to become familiar with the concepts and approaches to architectural design and fabrication research taken by some of the other top programs specializing in just that.

Working directly with experts in the field of computer-aided design during the ACADIA workshops was an undeniably beneficial experience. What was especially memorable though, was the effect these experts had on my own understanding of Michigan’s FabLab, and how I could use it as a MS student. Given that the school’s workshop consumes almost the entire lower level of the architecture side of our building, I had always assumed that I would not be able to see every tool in action within the short duration of my MS program. During the workshops, I was excited to see some of our most powerful (and often dormant) tools come to life, as visitors such as Brandon Clifford jumped on the opportunity to use equipment which is not as readily accessible to them at their own school’s facilities. But what was even more surprising were the tools and equipment that seemed to emerge from the shadows, as temporary classrooms were set up and new hands began to operate in these spaces. Within the course of three days I watched as our workshop was rearranged to reveal retired tools hiding in the corners, as powerful end-effectors were pulled out of storage, and as innocuous questions about random FabLab installations revealed the remnants of an entire research project. By the end of the third day in the ACADIA workshops, I found myself more excited than I had been the entire semester about the work I could produce as student.

As the conference continued, these observations were only furthered as lecturers and visitors commented on the challenges facing the field of computer-aided research and design. The projects I was exposed to during ACADIA made it clear that as computation and robotic tools are paired with materials and processes, architects and researchers today have a seemingly endless supply of research topics at their disposal. As a student, it feels as if there are endless directions to be pursued in computer-aided design and architectural research. Each day I learn a bit more about how end-effectors can be fabricated or hacked, how tool-paths can be precisely executed, about new materials I could be playing with, and software that could be developed to meet the demands of any project.

Capturing the changing nature of architectural research is no easy feat, but my program at the University of Michigan has tried to simplify the architectural research agendas by dividing its cohort into two groups; Material Systems and Digital Technologies. My own concentration, Material Systems (MS_MS), seeks to understand the inherent capacities and potentials of architectural materials, whereas the Digital Technologies (MS_DT) concentration examines fabrication which employs computation and robotic control.

Before I joined the MS_MS program, I worked as an Graduate Architect (or Intern Architect, if we’re still using that title) after earning my B.Arch from the Iowa State University. In practice, I rarely felt as if there was any space within the profession to dive deeply into a research project, and ask questions that have the potential to reshape and improve the field of architecture. Becoming a MS in Architectural Research and Design student has allowed me to step away from working as an architect for a year, and take the time to develop a methodology towards architectural research that could be taken back into practice. Studying at the University of Michigan has allowed me to gain access to an incredibly well-equipped fabrication lab to use in executing this agenda, but it wasn't until ACADIA that I realized the full potential of the facilities and the potential of what could be executed while enrolled in the MS program. Working with Brandon Clifford during the ACADIA workshops not only allowed for the opportunity to see how other top schools seek to tackle the growing field of architectural research and design, but also helped me develop a more meaningful understanding of what it means to pursue architectural research at the University of Michigan. To any student of architecture, I would highly suggest taking advantage of next year’s workshops at the 2017 ACADIA conference, hosted by MIT.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.