In the face of events that exceed our capacity for comprehension, humans tend to invent myths and stories that render things palatable. The passage of the sun across the firmament, the surge of the oceans in a storm, the crash of thunder that follows the flash of lightning – these all have been attributed to the actions of gods, demons, etc. Even when a more precise or scientific answer is available, humans tend to rely on these stories to help explain complex phenomena to children. What stories will humans of the future invent to understand our time of ecological crises? The Ocean Above Us Honorary Mention proposal takes the form of such a fable, sited in a speculative future in which humans reach to the skies to quench their thirst.

The Ocean Above Us, by Jake Boswell

“The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man. Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second.”

– Thomas Robert Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population. 1798.

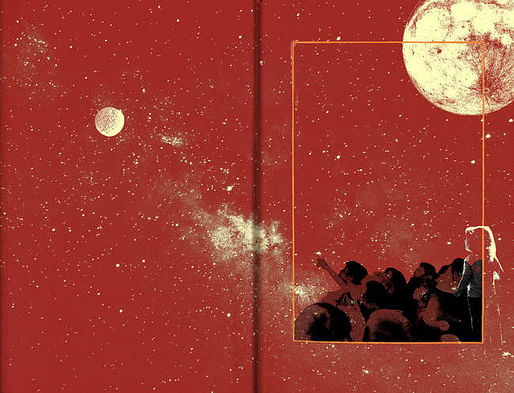

The Ocean Above Us is an annotated children’s story. The prose poem captures roughly 100 years of future history beginning with the drought and exploring the series of events that follow in its wake – eventually leading to the creation of the first space elevator. The project is inspired by the confirmation of water ice on the dwarf-planet Ceres – and the potential for that water to aid in human colonization of the solar system. The annotation explores this future history in greater depth, intentionally blurring contemporary and historic thought with future imaginings. While the content of the book is fictional, it is based in historical and contemporary scientific fact and well documented scientific speculation.

All imagery used in The Ocean Above Us is copyright free and has been drawn from either the Library of Congress or NASA.

Before I go any further, I should acknowledge that shipping water from space is not a solution to the immediate drought – but that really isn’t the point, is it? The California drought is bigger than California. It’s bigger than water. At some point the drought is merely a symptom of the great challenges facing the current generation: climate change, population growth, scarcity, resilience -- and of the lack of political will to address any of them.

In some ways The Ocean Above Us tries to play out the longstanding debate between Malthusianists and so called Cornucopianists. The former, following the general principle outlined by Malthus, suggest that resources are finite and that the human population – if left unchecked – will invariably bump up against the limits of those resources resulting in a subsequent, painful, reduction in population. The latter arguing that human invention - as spurred onward by necessity - will always overcome short term resource scarcity: agriculture will improve, new mines will be discovered, people will learn new ways of being and living in order to adapt. With the exception of Stewart Brand, malthusianists dominate contemporary conservation rhetoric. Conservation is a good thing. We should save. We should try to make the most of everything that we have. But the problem with malthusianist conservation rhetoric is that, at its extreme edges, it seems irreconcilable with democratic and humanitarian values. Because our population expands exponentially, as Paul Ehrlich is only too happy to tell us, the logical end game for extreme conservation measures is always population control. Population control, regardless of the process through which it occurs, should be chilling to anyone who values human life. Meanwhile cornucopianism seems to have fully sacrificed itself on the altar of neo-liberalism. The idea that all humanity needs is entrepreneurship, innovation, and a free market is laughable. While it may indeed reduce commodity prices in the short run, it does so at the cost of human dignity, long term sustainability, and, perhaps most damning, long term thought.

But wait. Why are we even talking about this?

The irony here is that so much of this debate has occurred post 1961. What happened in 1961? On April 12thThe Soviet Union put Yuri Gagarin in space. At that point humanity stopped being limited by the resources of our one, tiny, planet, and literally ascended into an era of unlimited resource potential. Theoretically, the Malthusian argument stopped holding water in 1961. Gerard O’Neil saw this fact when he published The High Frontier in 1977. O’Neil argued, persuasively, that extra-terrestrial habitation was possible -- given 1977 technology – and he noted that access to space could be the solution to what were also the pressing problems of his time – resource scarcity, the energy crisis, Ehrlich’s erstwhile population bomb, and even global warming.

Maybe it was Challenger, but, at some point during the culture wars of the 1980’s, we seem to have forgotten about space – at least most of us did. While we continue to defund the national space program in order to dump money into tax breaks and resource wars, space – and all that it offers --is still there. It’s just waiting for us.

As I write this a handful of private companies are making plans to move beyond Earth’s biosphere in search of precious metals. The “fireflies” mentioned in The Ocean Above Us, are the product of Deep Space Industries (DSI), a company hoping to be at the forefront of deep space mining. Will this new age of space exploration benefit all of humanity? Maybe. More likely it will just line the pockets of its investors. In either case, the thing I find admirable in the efforts of DSI and Planetary Resources and other companies bent on moving beyond Earth, is that they seem to actually have grasped where the future lies and they’re not sitting on their hands or wringing them. The thing I find horrifying about these companies is that they plan to privatize space. The recently passed Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act of 2015 guarantees private companies the rights to any materials they mine from asteroids. That such exploration probably won’t benefit the mass of humanity should be disappointing, especially given the promise and sacrifice of the early space program. But we are still at the beginning. Rather than shunting space exploration and habitation away to some distant future, we should be making plans for it and those plans should consider the ways in which all of humanity can benefit from and participate in this next great human adventure.

The Ocean Above Us is an attempt to bring back some of the hope and romance that the early space program offered with the intent of getting a new generation excited about space. Is this a short term solution to the California water crisis? No. But, I hope it points toward something much bigger.

-

From the judges:

"Curiously charming, a nice and unexpected entry." – Peter Zellner

"Testament to power of design to get our attention and focus it, and the potential for design+storytelling to re-frame parameters of debate." – Hadley Arnold, the Arid Land Institute

Check out the image gallery for The Ocean Above Us' complete presentation.

Click here to see the other winners in both the Pragmatic and Speculative categories!

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.