What I think about when I think about The Fast & The Furious... cultural geography, architecture and landscapes of the blockbuster film series. Originally posted on my Medium blog.

---

Escape Velocity

American Identity in The Fast & The Furious

“Americans cleave to the things of this world as if assured that they will never die […] They clutch everything but hold nothing fast, and so lose grip as they hurry after some new delight. […] At first sight there is something astonishing in this spectacle of so many lucky men restless in the midst of abundance. But it is a spectacle as old as the world; all that is new is to see a whole people performing in it.”-Alexis De Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1840).[i]

-

The Fast and The Furious. 2 Fast 2 Furious. The Fast and The Furious: Tokyo Drift. Fast & Furious. Fast Five. Fast and Furious 6. Furious 7. The Fate of The Furious.

Two more films are promised. The Fast & Furious franchise is incredibly popular, and while not apolitical, they have a widespread appeal that cuts across political lines. These are distinctly American films, not only due to their subject, style, and provenance, but due to the way the series, taken as a whole, is revelatory of key aspects of American[ii] identity. I don’t really give a damn about the meta-textual behind-the-scenes feuds, actors lives, or directors’ careers outside of the franchise, except in how these inform the narrative.[iii] This essay is not concerned with cars at all (and not least the difference between “American muscle” and “Japanese tuners”), except inasmuch as the automobile as a device epitomizes the centripetal/centrifugal duality at the core of this essay: the private car on the public freeway, a centripetal bubble of private, domestic space with the capacity to traverse vast centrifugal geographies of the public realm.

Beyond the ever-increasing pendulum swing of our two-party political system, American identity has always been bipolar, if not schizophrenic, simultaneously rooted in fear and mastery, naivety and expertise, insular yet expansive. This identity crisis can be traced to the dual or multiple founding(s) of the country: Protestants and Anglicans, rebels and royals, federalists and republicans, slaves and free men. While American identities are myriad, for the purposes of this essay I’d like to file the essential traits of American identity into two main categories:

1) The Centripetal

2) The Centrifugal

1) “Centripetal” is defined as “moving or tending to move toward a center.” In this essay, I interpret this centering impulse as a strain of American identity/mythology that prioritizes: the importance of family and community; increasing inclusivity/diversity (a bringing-in); reinforcement or repetition of beliefs/ideals; conceptual “circling the wagons;” the importance of home or refuge; the re-establishment of a status quo. The centripetal is “conservative” in the sense that it is cautious and inwardly focused.

2) “Centrifugal” is defined “moving or tending to move away from a center.” I interpret this outward impulse as prioritizing: individuality as opposed to community; entrepreneurship; expansionism; exploration; departure; prospect; the unknown. The centrifugal is “progressive” in the sense that it is risk-tolerant and outwardly focused.

These dual and dueling impulses do not necessarily align with the tenets of any political party; this is a primal duality borne of primate evolution. “Prospect & Refuge” theory gives this duality a psychological-spatial form[iv], but every conscious animal can recognize the difference between exposure and safety. In truth, it is the tension between centrifugal and centripetal aspects that forms the core of American identity: these unresolved contradictions propel and sustain the “becoming” of a “more perfect union.”

These categories merge in the archetypal narrative of the American frontier. The idea of “the frontier mentality” as a key aspect of American identity can be traced back to 1893, when Frederick Jackson Turner presented his thesis “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago.[v] Recognizing that US territorial expansion had reached its continental limits, Turner proposed that the expansive impulse (pioneers, followed by settlers, on an ever-westward trajectory) was key to American identity. In the frontier mentality, exploration into the unknown is the driving impulse, yet personal relationships are paramount in the face of a dangerous and uncertain environment. An expansive outlook is necessary to forge ahead, yet forging a community is required to maintain a foothold for civilization in the wild. A growing functioning society requires laws, but these are arbitrary, to be questioned. The “frontier” synthesizes the centrifugal and the centripetal.

While it should come as no surprise that an action movie franchise “about” fast cars embodies a longstanding aspect of the American mythos, the Fast & Furious series embraces this contradictory dualism as much as does the USA itself. Are these movies politically charged or apolitical? Is the series, as in the old cliché, a mirror held up to society? The Fast & Furious movies are dumb. But they are “dumb” in the sense of being non-verbal, in which action speaks louder than words, and the stories that play out on-screen trace arcs that are ingrained in our collective human memory. The soap-operatic F&F plots are beyond cliche: they are archetypal narratives of family and community, identity and self-actualization, transgression and redemption. The American mythos is constructed of a heterogeneous mash of such stories; those interwoven histories that make up our collective self-identity.

Part 1: Centripetal

Family & Community

“I don’t got friends. I got family” -Dom, F7

In F1, Dom (Vin Diesel) describes how his father died in a crash, events that propelled him to a life of crime. This is among the vanishingly-few times a parent of a main character is even mentioned, let alone given a backstory. For a series so ostensibly focused on “family,” it’s surprising how few parent/child relationships are explored. Of the core cast of characters, only Dom has a parental backstory: his father died in a race, propelling Dom to a life of crime. Dom describes this to Brian (Paul Walker) in F1. In F5, Dom gives Brian another anecdote, describing how his father would help his sister Mia (Jordana Brewster) with her homework, reading a chapter ahead in advance. The Brian-Dom relationship vacillates between antagonist/peer/brother, but the defining characteristic is Dom as patriarch, replacing Brian’s absent father.

There are several children in the films, serving mostly as kidnap victims and character motivation. Children in F&F are often named after main characters of the previous generation, usually of no blood relation, as tribute: Vince (Matt Schulze) names his son Nico, after Dominic; Dom names his son after Brian.[vi] The lack of attention to biological lineage in the films coupled with the repeated mantra of “family” proves the point: in the F&F series, family is a social construct, based in personal choice, not genetics. The ties that bind are moral/ideological rather than biological. This ties in neatly with the films’ concept of identity as something that is proven or established through action (see below). If “family” is defined by an in-group, shared-morality belief system, rather than genetic ties, then inclusion in that family is fungible, and the family can expand in unconventional ways. As the series progresses, Dom’s family expands and becomes more diverse, but Dom remains the clear patriarch, “like gravity,” Mia explains to Brian in F1, “everything gets pulled to him.” Dom’s family is inclusive but hierarchical, a structure that is re-established at the conclusion of each film.

Gender

“Any of this feel familiar to you?” — Dom

“No. But it feels like home.” — Letty, F6

Dom’s role in the “family” hierarchy is indicative of the series’ attitude regarding gender roles. As the series progresses, women are given more power and agency with each new female character that is introduced. Giselle (Gal Gadot) weaponizes her body/sex appeal on several occasions, but she is generally shown as competent and in control of every situation, and this is not diminished by her relationship w/ Han. Ramsey (Nathalie Emmanuel) shows expert confidence throughout F7 and F8, even as the scenes heavily forecasts a relationship w/ Tej (Chris “Ludacris” Bridges) to come. But, simultaneously, the stylistic objectification of the female body becomes more extreme as the series goes on, particularly in the dance montages that accompany seemingly every change of location or run-up to a race. Can a film series that objectifies women simultaneously celebrate their agency? One of the series’ main failings is that while it allows the women on the main cast agency, control, and nuance, the rest are reduced to objectified eye-candy.

Even more troubling, characters introduced early in the series find their agency gradually stripped away, especially when the plot demands that they become subservient to accommodate a male story arc. Mia, shown to be a proficient driver in F1, and a key member of the team in F5, is sidelined from F6 onward, functionally disappearing from the narrative in F7. Letty, a key member of Dom’s crew, and his seemingly-equal partner in F1, is unceremoniously killed off in F4, then returns in F6 as an amnesiac beholden to Dom to refresh her memories. These women are stripped of their power, an example of “expansionism” wherein men become more powerful while women are increasingly oppressed. “Dom’s” domination of increasingly permissive “Letty” in later films is particularly troubling.

One might argue that all characters in the film lose shades of nuance as the series progresses, with the relative realism of F1 serving as a kind of superhero back-story; in later chapters the characters become archetypes, defined by their superhuman abilities, and quippy catch-phrases. Yet while the men in F&F are always advancing, the women cycle between advancement and repression, as in America.

Repetition & Redemption

“Ride or die, remember?” — Dom to Letty, F6

Dom is introduced as an ambiguous character, but by the end of F1 the writers have laid down their cards: Dom is the moral center, the gravity that holds the “family” together. The moral code of the F&F is reinforced through repetition. Taken as a whole, the F&F series does not play out like seasons of a TV series, or like the metastasizing complexity of the Marvel cinematic universe. Rather, each movie has essentially the same core group of characters and similar plot points and narrative structures. While F4 was a near-reboot, F2 and F3 remain part of the main continuity — there are no alternative universes here. Each subsequent film is a kind of repetition of the last, hitting many of the same beats, but updated and improved upon, freed of the burden of originality in structure or essential form.

You could drop into any of the films and very quickly get up to speed: the main cast has expanded over the course of the series through the questioning and switching of loyalties (via amnesia, deception, or change-of-heart, etc) [vii], but in general the core group remains the same, and in-group status is continuously proven and confirmed through action. At the end of each film, the status quo is generally restored, with minor adjustments, such as change of location, and the adoption or ‘conversion’ of antagonists to the protagonists’ side, a redemptive arc that has replayed several times in the series.

Dom’s actions in F1 prove morally right in the characterization of the script, and to Brian, the audience surrogate. The in-group associations of religious orders and crime syndicates alike are echoed here in Dom’s crew, but the films place the viewer firmly on Dom’s side from F1 onward, and the rightness of Dom’s moral philosophy is taken as a given. Thus, each flipped antagonist serves to reinforce this rightness.

F1 concludes with Dom and Brian in an uneasy truce, when (cop) Brian lets (criminal) Dom walk, breaking his loyalty to the state. In F4, Giselle (Gal Gadot), a lieutenant of the antagonist drug cartel, eventually comes to the aid of Dom’s crew, which she joins full-time in the following film. In F5, the core team is established (or reconvened), and the secondary antagonist, Hobbs (Dwayne Johnson), is rescued from attack by Dom, and returns in F6, to offer Dom’s crew a job, essentially becoming a part of the team. In F8, the primary antagonist from F7, D. Shaw (Jason Statham), becomes another hired-gun on the same side as the heroes, and is joined in his efforts by his brother, O. Shaw (Luke Evans), the antagonist from F6, by the conclusion. One might expect hacker Cipher (Charlize Theron), F8’s villain, to return in F9 as an uncertain ally. When these antagonists are “saved” by the core crew, if they don’t quite become part of the “family” they at least acknowledge the concept of morality offered by Dom and his crew, as in Shaw’s reluctant redemptive arc in F8.[viii]

Similarly, when members of the core team are compromised, they will always, eventually, return to the fold. F4 concludes with Letty’s apparent death, and in F6 she returns as an amnesiac, having been recruited by the cartel. Throughout the film she questions her motivations, and — without regaining her memories — she rejects the cartel and returns to the side of good with a literal leap of faith. When Dom is apparently compromised by Cipher in F8, it is quickly revealed to the audience as blackmail, and he eventually returns to the team, in spectacular fashion. The series’ “ride or die” mantra becomes a moral decision point and a question of in-group identity: are you part of the family, or not? Are you in or are you out? Taken together — that the antagonists often turn, and that protagonists, when flipped, always return, can be seen as a way for the movies to establish their moral code. That Dom and the crew always do right by family is a key theme of the series, as proven by these switches of loyalty.[ix]

Identity & Morality

“Look, just because you know how I ride, doesn’t mean you know me.” -Letty to Dom, F6

The films are packed with examples of characters who revealing their ‘true selves’ through actions that prove their acceptance of Dom’s worldview, and result in absorption into the “family.” The detente reached between Brian and Dom at the end of F1 quickly evolves into friendship and reconciliation in the face of a common enemy in F4. Vince, a foil for Brian in F1, offers his home as a safe-house in F5. Identity in the Fast & Furious series is innate, and best expressed through action. When Letty says “you don’t know me” to Dom, she’s quickly proven wrong. In this universe, you are defined by your actions, and thus each new experience offers the chance for reinvention. Is this a key of the American mythos, the second chance, the resurrection? There is surely a strain of American morality that is based in Abrahamic religion, tales of prophets and the redemptive power of belief and faithful action.

The films are not explicitly religious, but the moral reinforcement is a secular ethos that acts as a stand-in. The F&F morality is a secular religion whose tenets are vague enough to win widespread appeal, and the few explicit religious symbols, like Letty/Dom’s cross necklace, are given primarily personal meaning. Atheists, agnostics, and the faithful alike find no fault with the films’ appeal to family, community, and the importance of a moral code. Ultimately, the intersubjective truths embraced by Dom’s crew feel “right” and familiar to viewing audiences of all political and religious ideologies.

Family, repetition, conversion/redemption, the re-establishment of the status quo; these are all themes of the F&F series in its’ “centripetal” inward-focused mode. Norms are reinforced, family bonds are strengthened. Insular. Domestic. Familiar. Next we’ll look outward.

Part 2: Centrifugal

Geography

If one key aspect of the F&F films, and of the American mythos is the inward, the centripetal, another is its opposite: the outward, the centrifugal. Key to this strain of American identity is expansionism, that seeking impulse that drove the first transatlantic explorers and settlers to cross the sea; that sense of privilege and territorial drive that led to indigenous genocide and continental occupation; that led to California, setting for much of the Fast & Furious series.[x]

In purely geographic terms, the F&F series continues this expansion beyond California as each subsequent film reaches further out into the world: F1 sticks to LA; F2, Miami. F3 is set in Tokyo, and F4 returns to LA and the Mexican border. Beyond that, the series expands exponentially: to South America, Europe, Cuba, Azerbaijan and its airspace, and Abu Dhabi. F8 concludes with a battle/race on an arctic ice floe, while villain Cipher (Charlize Theron) is totally de-territorialized: her “base” is a flying fortress that surfs radar blind spots. (There may be only one logical place for the series to go next; and Elon Musk has already sent a Roadster.[xi]) But beyond the physical geography of the series’ settings, the F&F films evince an expansive concept of cultural geography that mirrors the 20th century expansion of US hegemony. The California coast is where the impulse towards geographic expansion hits a physical limit, and is transmuted into dreams of fame and fortune, of reality transmuted into fantasy, of the climbing and surmounting of hierarchies of power, of the physical into the digital, into the questioning of time, space, and reality itself. From the 1840s gold-rush entrepreneurs and “Manifest Destiny” to the 1960s counterculture, California has been on the breaking edge: a driver of culture and commerce, a test bed for political ideas, a haven for the odd or misunderstood, or the recently-immigrated, or the un-assimilated. The expansionist impulse brought the US to both coasts of the continent; and California is where that impulse moves from geography to culture.

It’s worth recalling how outsize an influence California’s purveyors of fantasy and narrative had on US expansion beyond its physical continental limits. William Randolph Hearst, famous newsman, propagandist, and Hollywood playboy famously wrote: “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war” regarding US involvement in the Cuban republican revolution / Spanish American War. US hegemony was made possible in part through the aid of Hollywood and ethically-questionable journalists who recognized the power of a well-constructed narrative. The role of “yellow journalism” in justification of US imperial ambition is well known, but recall that the US began expanding its colonial empire just as cinema began to develop as an art form, and the “soft power” cultural dominance the US held through the Cold War era was buttressed by the easy transmission of US media around the world.[xii]

But back to California. Los Angeles is one of the great world cities, a true demographic melting pot, and a place where most anyone can live and find community. While LA’s sprawl reflects the expansive impulse on the scale of a city, it is in the worlds of subcultures where that impulse is expressed most freely. Reyner Banham writes of four such “ecologies” in his Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971), the fragmented nature of that book’s structure itself revealing something of the multi-valent LA culture. Each of Banham’s “ecologies” can be seen as centrifugal: surf culture[xiii] as the pursuit of physical excellence and the domination of a natural phenomenon; the “foothills” as a pursuit of capitalist luxury; Hollywood as producer of fantasy, and “autotopia” as emblematic of the perceived freedoms of the highway system. However, the freedom Banham proposes as inherent in the highway system requires “willing acquiescence in an incredibly demanding man/machine system”[xiv] The apparent freedom of driving is constrained by the rules of the road and the physical topology of the highway system. While that freedom is illusory, he suggest, it is nonetheless subjectively liberating, a productive fantasy that fuels the centrifugal impulse.[xv]

Architecture & Landscape

The “architecture” of the F&F series is best understood as the “natural” landscape or the urban, metropolitan field. The first film does feature several prominent interior settings: Mia’s lunch counter with Dom’s office beyond; Dom’s garage; Dom’s house; Brian’s corporate auto-parts store and police sting house. In later films, the domestic/residential settings mostly drop out of the storylines: Dom’s house is literally blown apart in an inciting incident in F7; after Brian and Mia are written out of the narrative following Paul Walker’s death, F8 features almost no domestic spaces, only workshops, garages, warehouses, offices. As the series progresses, Dom’s garage grows from a modest shop in F1 to an infinite Raisers-of-the-Lost-Ark warehouse of seized vehicles in F8.

But from F2 onward, the primary settings are exterior: the landscape is the natural habitat of Dom and crew. Much as the Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote cannot exist outside of the desert highways of the American southwest, Dom’s crew is most at home driving the California coast.

When the crew is challenged by plot machinations, they are often placed in different landscapes; their success at navigating these landscapes is commensurate with the similarity to the archetypal cliff-side coastal road, or the broad dessert expanse. Like California’s coastal Route 1, the South American mountain road that opens F4, and the Azerbaijan mountain highway in F7 are twisted, craggy landscapes where a bad turn could spell doom; the ice plains at the conclusion of F8 mirror the dusty desert of the “Race Wars” scenes in F1 and F6. Dense urbanism is another major setting for the series, but city scenes are always tense: there seems to be more at stake in the relatively constrained space of a city grid; which causes consternation for protagonists and antagonists alike. The confines of the city lead to spectacular destruction when our protagonists are set outside of their comfort zone. When Brian “departs” at the end of F7, his send-off is on a coastal road, not sitting in downtown traffic. When Cipher swarms NYC with hacked self-driving cars, the mayhem that ensues is clearly un-natural: the cars are not in their ideal environment, the open road.

Yet these mountainous and desert environments are hostile to humans alone, only appropriate for the cyborg subjectivities of our car-human hybrid protagonists. Like shedding skin, Dom can take leave of his technological carapace when threatened or when the action otherwise demands, like a snake shedding skin, a hermit crab upgrading shells, or a starfish losing a limb to escape a predator. In the “tank chase” scene in F6, Dom ejects from his car to catch Letty in mid-air, discarding his shell in a moment of courage/desperation. When Dom’s beater is engulfed in flame in the Havana race that opens F8, he jumps and rolls, sending the car plunging into the sea. At the conclusion of F8, Dom hurls his vehicle towards the enemy submarine’s fin. Like a cornered animal, Dom sheds his technological shell as a survival mechanism, in a rush that exposes him while simultaneously allowing his escape and/or inflicting more damage on his opponent. Without the technological shell, these characters are exposed, vulnerable.

Culture, Race & Demographics

While F1 is primarily the story of a white man’s self-actualization and romantic pursuit, the subsequent movies expand the cast to a multi-ethnic ensemble. Vin Diesel identifies as multi-ethnic[xvi]; and while his character Dominic Toretto’s heritage is never stated outright, it’s worth remembering the discrimination faced by Italian Americans in this country’s living memory. Even without debating the concept of whiteness as a social construct and a category in continuous flux, it’s clear that the F&F series’ main cast is incredibly diverse in comparison with other similar action movie franchises. [xvii]

Early in F1, we meet a variety of racing crews, apparently grouped by race: Latino, Asian, and Dom’s crew majority white. In one of F1’s movie’s climactic scenes, the crew goes to “Race Wars” — a competition on the salt flats that pits these ethnic groups against each other. There is no subtext.

In F2, Brian is joined by Roman (Tyrese) and Tej in the main cast. In F3 the action moves to Tokyo. Thus the first three movies of the series represent a continuous broadening of the racial inclusivity of the main cast, and perhaps a ploy for expanded box office demographics. F4 brought back main characters Brian, Dom, Letty, and Mia, while F5 includes seemingly every major character from all previous movies (including a ret-con of F3 as a flash-forward, rather than a non-canon spin-off.). So, by F5, the series has an expanded on-screen demographic of white, black, multi-racial, Hispanic, Asian, pacific islander, Israeli, etc. But while minorities are increasingly empowered, they still play a secondary role, with limited agency (see Roman’s leadership plans in F7 and F8), and all characters regardless of race are subject to hierarchies of power.

State / Power Hierarchies

“It wasn’t half bad, having you work for me.” — Hobbs

“We all know you were working for me, Hobbs.” -Dom, F6

Another example of the F&F in its expansive mode is in the changing relationship between the core crew and the institutions of the state. Each subsequent film reveals a higher level of state power, then reveals its’ innate corruption in the comparison with family loyalty. The implication is that the individual and family is ultimately superior to the state, that the state works, or should work, in the family’s service.

In the movies, there is always a higher-up. As in video game logic the next layer is only revealed when the last has been made subservient, or at least, brought into the fold as an ally of Dom’s crew. So, when Brian lets Dom go in F1, he gives up his role as a local cop. In F2, Brian has, by plot contrivance, become an FBI asset (federal), and by F4 he is a full-fledged agent. The FBI is then superseded by the (diplomatic) DSS, in the person of Hobbs in F5. In F7, the DSS is supplanted by “Mr Nobody” (Kurt Russell) and his mysterious but infinitely-funded and globally-connected organization. In each subsequent film, the crew advances up to another step in the hierarchy of institutional state power. This advancement also serves to free the team from economic constraints. Where the cost of upgrades, prize money, etc, was discussed in F1, the final heist in F5 provides previously unheard-of wealth to the crew, and by F8 their association w/ Mr. Nobody renders questions of financing irrelevant. Thus both financial and legal constraints are revealed as moving goalposts, the concept of law as fungible and the expansion of power practically unlimited for our protagonists.

Spectacle / Fantasy

“Dom, cars don’t fly. Cars don’t fly!” — Brian to Dom, F7

Ultimately, the F&F series is about ever-increasing spectacle. In each subsequent movie of the F&F series, the budgets are bigger, the stakes are higher, the jumps are longer, the crashes more spectacular. The realism of the first is almost shocking when revisited after watching F7 or F8, but the progression is not illogical.

In F1, the races are intense but believable, and the heists are choreographed with human emotion at the forefront — as in the extended semi-truck sequence when Vince hangs from the door of a truck, arm caught wrapped in a grappling hook wire. The most intense stunt work was a jump from one moving car to the hood of the next. In F2, we get “some Dukes of Hazard shit” per Roman’s in-action commentary to Brian, as they ramp through the air to crash headfirst into the back of the villain’s boat. In F4, a climactic scene features a race through tunnels below the US-Mexico border, and F5’s heist culminates with two cars dragging a gigantic vault through the streets of Rio. In F6’s tank chase, Dom flings himself from his car to catch Letty in mid-air, which is followed soon after by the “endless runway” scene in which the crew chases down, harpoons, and crashes a military cargo plane mid-take-off. In F7, “cars don’t fly,” yet the crew skydives in their vehicles, landing on a mountain highway, then, later, steals a “supercar” from a high-rise party in Abu Dhabi, crashes it through the curtain wall, through the air, to crash into an adjacent skyscraper. Twice. Later, the crew destroys downtown LA with missiles, while Dom and Shaw enact a choreographed sword fight with giant wrenches. In F8, hacked self-driving vehicles swarm New York City; later, the crew chases down a nuclear submarine across an arctic ice floe. All of these scenes really happened in these movies. What could F9 possibly have in store?

Conclusion: Escape Velocity

Why are these movies so popular? The American affinity for absurdist spectacle is well-noted, by everyone from De Tocqueville to Barnham, to Banham, to Twain, to David Foster Wallace (and everyone else). Surely, blockbuster escapism plays a part. But the films also reveal key insights about American identity. The centrifugal/centripetal lens is useful for identifying conflicting impulses in the American mythos.

Border wall isolationism notwithstanding, the idea of expansion still resides deep in the American identity[xviii]. Individual liberty and entrepreneurship are inexorably linked with domination & oppression (to civilize the “savages,” to tame nature, or oppress minorities). Frontier individualism is ultimately tied to that other keystone, the family. As the rugged frontiersman makes the wilderness acceptable for civilization, for women and children, the narrative arc moves from centrifugal to centripetal. These myths of American identity drove settlers across the continent, then around the world as the US absorbed the ruins of Spain’s colonial empire just as media culture began to reach a global scale, as increases in speed of transportation and communication (steamships, telephone) enabled the rapid expansion of American cultural reach.

US “soft power” expanded concurrent with the post-war US-brokered peace, and US expansionism grew from a geographic phenomenon to a social and economic one, a trend which continued and accelerated through the end of the 20th century. That the shock of 9/11 and the ill-conceived wars in the aftermath, along with compounding demographic and economically-drive geopolitical isolationism have diminished this expansionist impulse does nothing to reduce the idea of generalized expansionism as an essential aspect of American identity. The Fast & Furious series is an expression and celebration of this aspect of the American psyche.

No mere escapism, these movies represent 21st century America in a deep and profound way. The F&F movies are increasingly more inclusive demographically, more expansive geographically, and feature ever greater feats of superhuman ability and ever-greater vehicular spectacle, while simultaneously holding back female characters, casting minorities in subservient roles, and letting US hegemony go largely unquestioned. That said, an inherent optimism suffuses the series, reassuring us that the morally right will win out over the lawful but compromised. The series reflects a continuation of “American expansionism” from geography to demographics to culture to the virtual and deterritorialized digital ether.

Ultimately, what these movies are “about” is this expansive impulse. Each movie must surpass the last, and while plot lines repeat and character arcs echo, the movies are propelled ever-forward, each new version of the narrative reaching ever-greater heights of absurdity and spectacle [xix]. As the geographic field of play is expanded, the power hierarchies of the world are revealed. As the speeds increase, the narratives move farther away from realism and further into fantasy. From centripetal to centrifugal, each subsequent film is faster, more furious, more likely to to reach escape velocity and find release, liberty, actualization, freedom, America.

Evan Chakroff March 6, 2019, Seattle

Exhibits

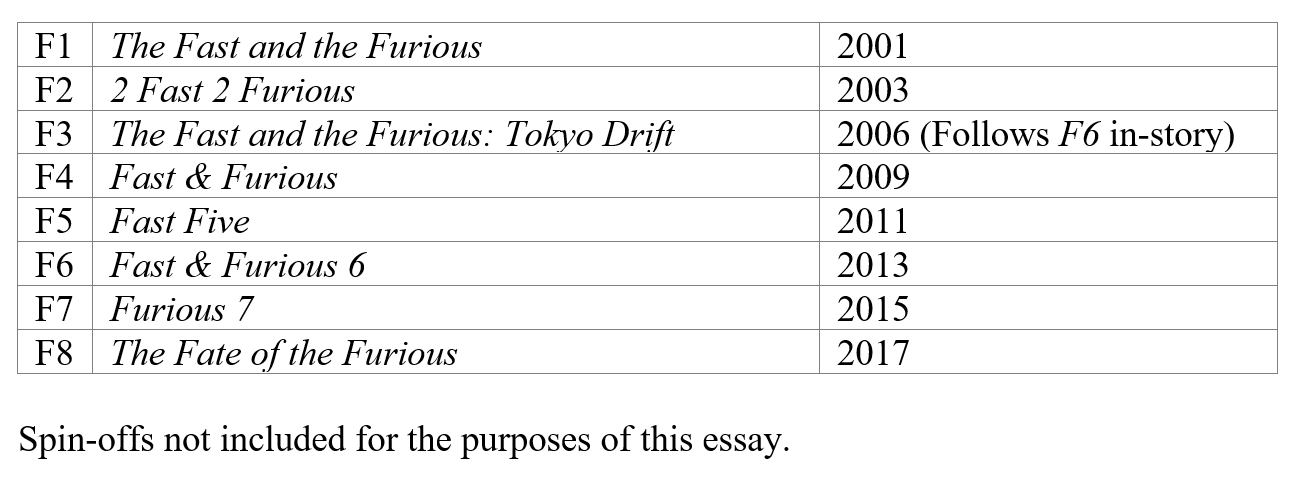

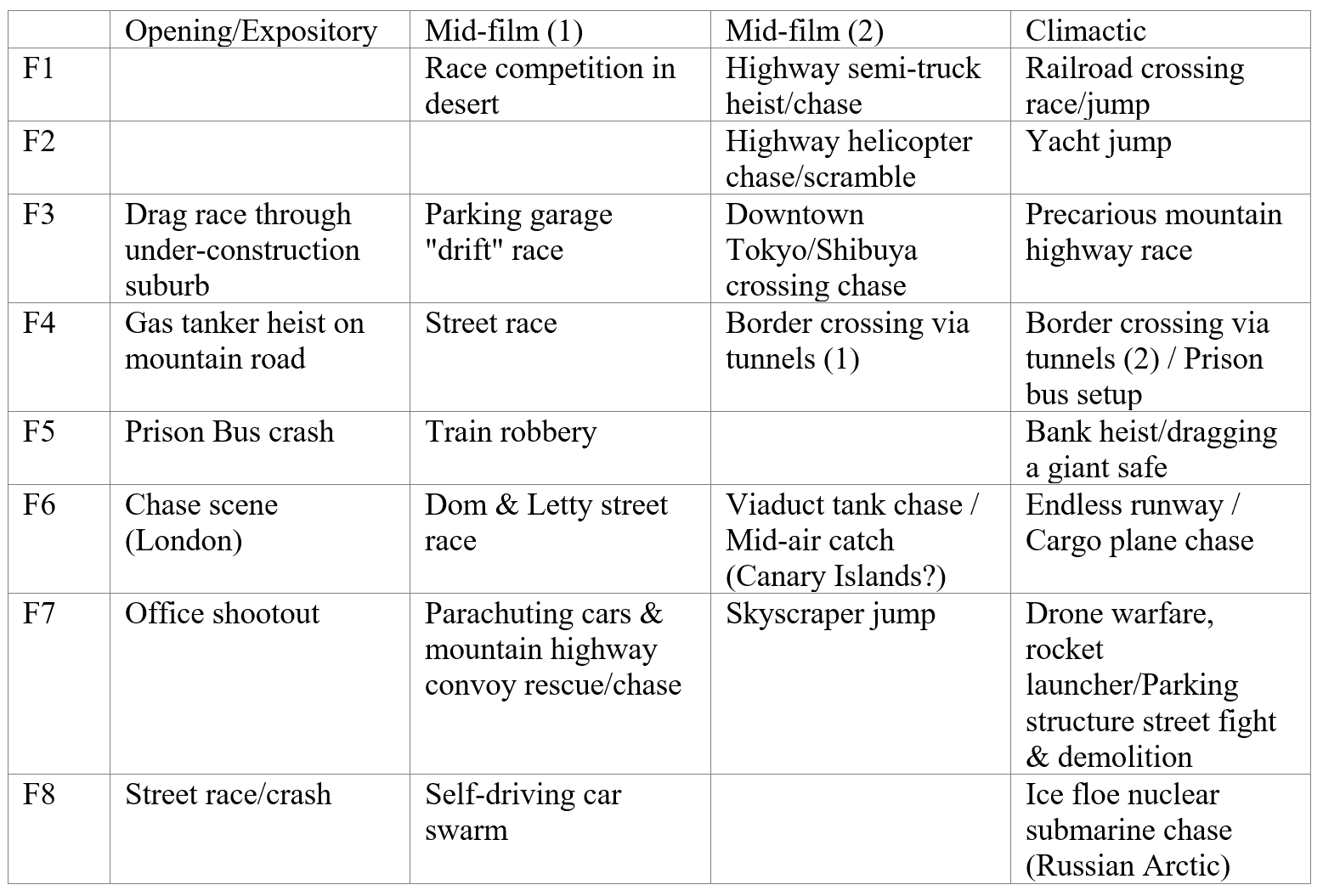

Table 1: Titles by Release Order

Chart adapted from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_The_Fast_and_the_Furious_characters

Table 6: Named Plot/Filming Locations

F1: Los Angeles F2: Miami F3: Tokyo F4: Los Angeles, Mexico Border F5: Rio de Janeiro F6: London, Los Angeles, Canary Islands F7: Los Angeles, Azerbaijan, Abu Dhabi F8: Havana; Berlin, New York City, Russian Arctic

Endnotes

[i] ed. J. P. Mayer, trans. George Lawrence, vol. 2, part 2, chapter 13, p. 536 (1969). Originally published in 1835–1840. https://www.bartleby.com/73/86...

[ii] In this essay I use “American” to mean the people, culture, and identity of the United States of America

[iii] This was written in early 2019, before Hobbs & Shaw, and before F9 and F10, and any other forthcoming spin-offs, were released.

[iv] “Prospect and Refuge theory” was first proposed by Jay Appleton in “The Experience of Landscape” (1975), and elaborated by Grant Hildebrand in an analysis Frank Lloyd Wright houses. A brief history: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286123657_Prospect_and_refuge_theory_Constructing_a_critical_definition_for_architecture_and_design

[v] A brief outline of Turner’s theory: https://www.pbs.org/crucible/tl2.html — or read the full text here: http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/gilded/empire/text1/turner.pdf

[vi] Oddly, Brian & Mia’s two children don’t follow this pattern: “Jack” and “Unnamed Daughter.” Hobbs’ daughter, is an outlier as well, bringing the total of outliers higher than those that supposedly prove my point. Damn. Hobbs’ daughter, incidentally, is the recipient of the cheesiest and most awesome quip in the series: “Daddy’s got to go to work” as Hobbs flexes his arm, cracks out of a plaster cast, then enters a riot-gear suit-up montage.

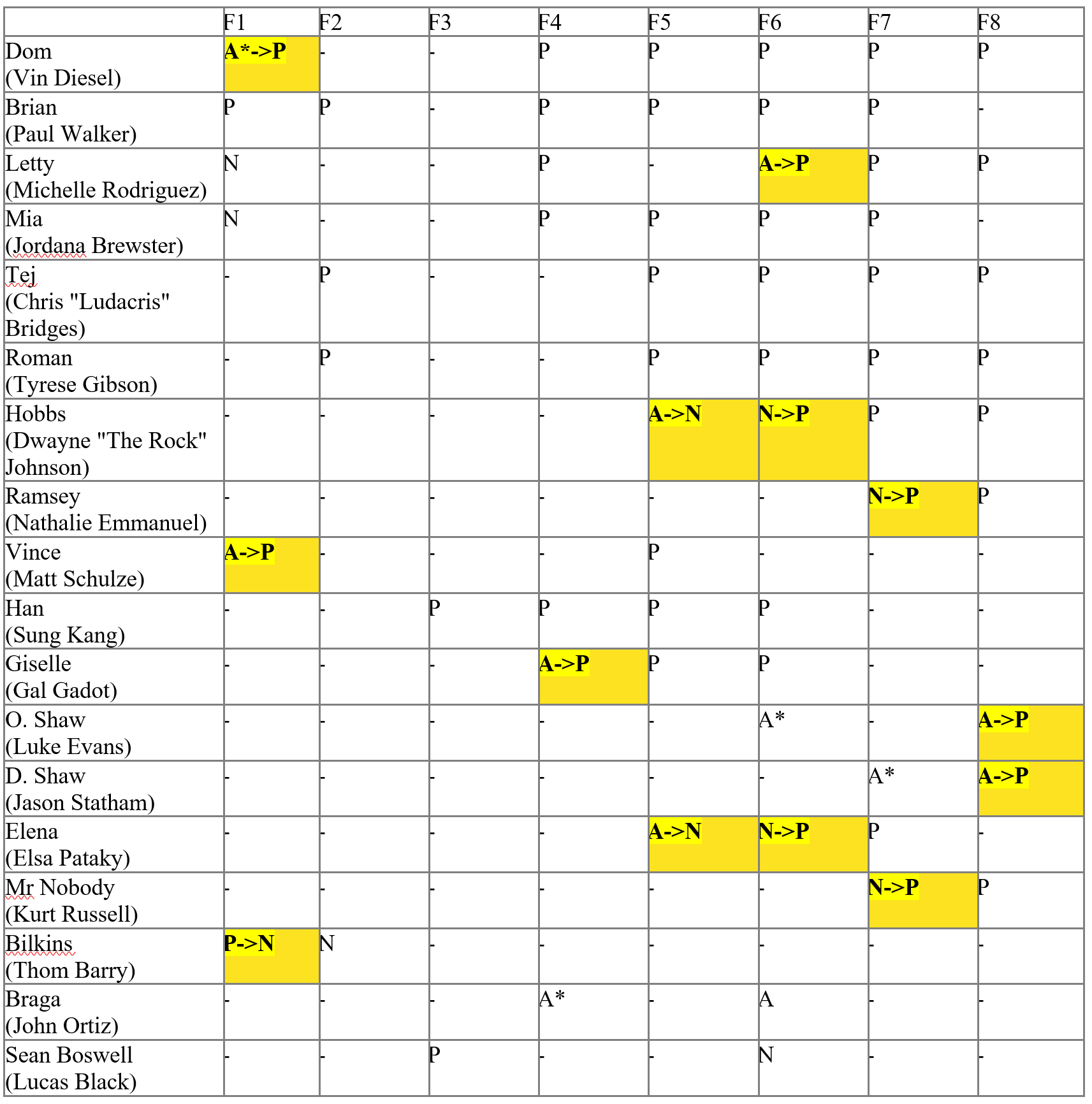

[vii] see Table 5

[viii] when Shaw is hired as one of only two people who could possibly track down a rogue Dom, leading to much flirty banter w/ Hobbs

[ix] That the same story essentially repeats, but with a “synthesis” of antagonists and protagonists suggest a kind of Hegelian dialectic or Joseph Campbell narrative arc: Dom’s view of the world is tested; Dom’s antagonist presents an alternative view of the world. Dom’s and his antagonist’s views are put into conflict, and emerge changed and combined. Though there is repetition, there is also forward motion and the accumulation of history.

[x] Oakland’s museum of California outlines this progression well: its California history exhibit recasts outlines the progression in cultural-geographic terms, as a through-line of “California-ness” is traced through history, present regardless of any imposed political entity: Spanish colonial, Mexican revolution, US colonial, statehood, etc. A future “CalExit” room is easily conceivable.

[xi] There is a line in F8 regarding one of the cars: “It’s bright orange! The International Space Station could see it coming!” Foreshadowing? Regarding Musk’s roadster, see, for example: https://www.space.com/42337-spacex-tesla-roadster-starman-beyond-mars.html

[xii] I wonder, but haven’t researched, if any funding for these, or, say, the Mission: Impossible films comes from the Pentagon. F8, at least, was funded in part from Chinese government-associated sources, suggesting a Chinese play for cultural hegemony in the 21st century.

[xiii] F1 was possibly conceived as a “Point Break” homage with cars subbed for surfboards: writer Gary Scott Thompson, in an interview kinda-acknowledges “We sort of do what they did in Point Break, and he goes undercover in this world.” https://www.complex.com/pop-culture/2016/06/fast-and-furious-columbine-shooting

[xiv] and: “The private car and the public freeway together provide an ideal — not to say idealized — version of democratic urban transportation (…) [but] (…) what seems to be hardly noticed (…) is the almost total surrender of personal freedom for most of the journey.” All p199.

[xv] This suggests some parallels between frontier narratives and car/highway culture and a cultural affinity between the Road trip and Western genres.

[xvi] “Diesel has self-identified as “definitely a person of color” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vin_Diesel

[xvii] Mission: Impossible, for instance

[xviii] See, for example, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/03/11/when-the-frontier-becomes-the-wall

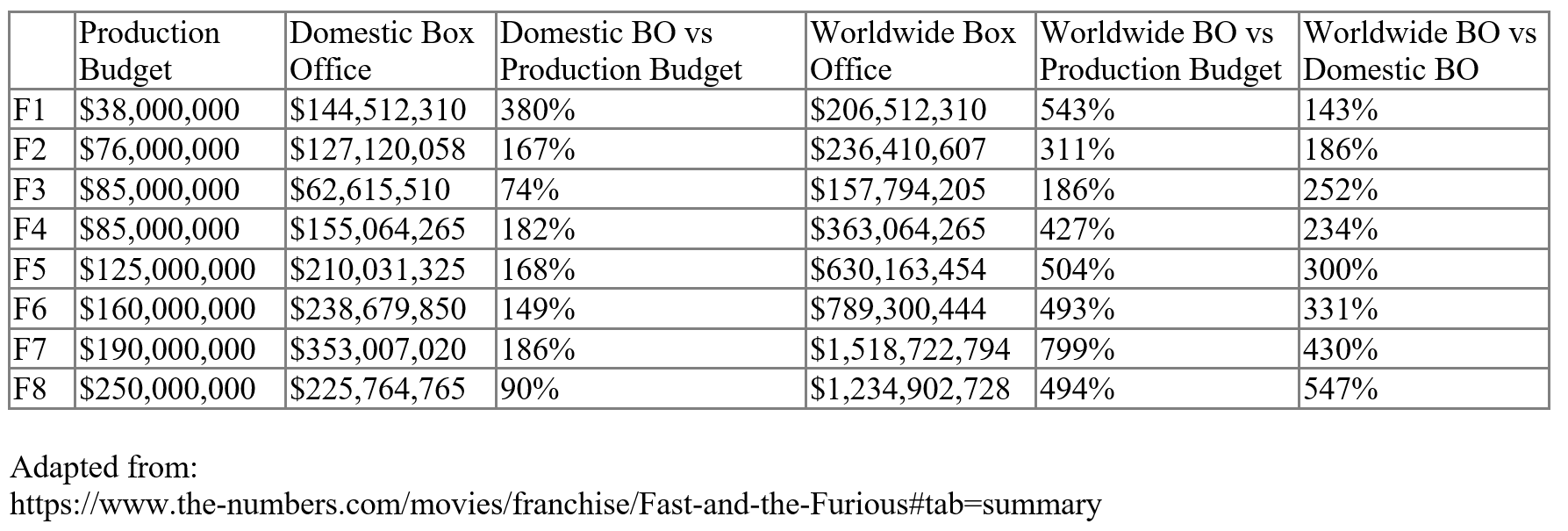

[xix] and, for the most part, ever-greater and greater box office returns — See Table 2

Returning to the US after years of work and travel abroad, Evan Chakroff attempts to bring a global perspective to analysis of the relatively-unknown architectural traditions of his new home, Seattle, Washington.... and beyond....

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.