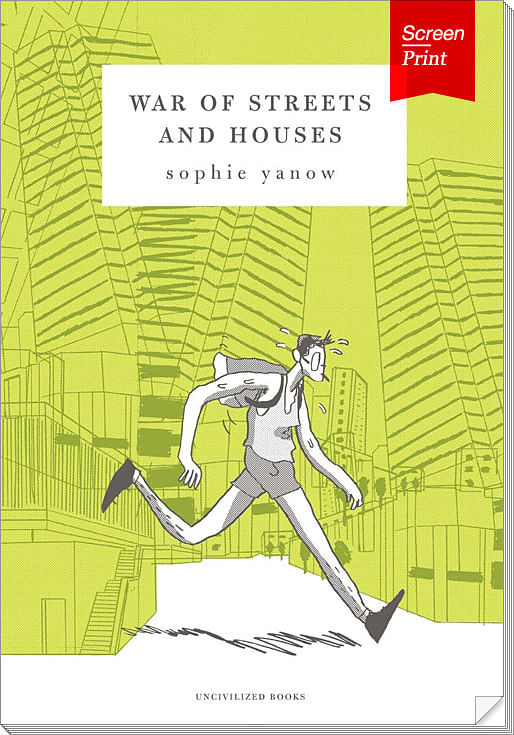

Student protests broke out in Montreal in February of 2012, rallying against Quebec’s proposed university tuition hike. The protests were massive, flooding the streets for days with students, sympathizers and police, while universities saw dramatic student walkouts. Sophie Yanow was one such sympathizer, whose experience in the protests made her reconsider the city as a place where systems of control are made physical. Her graphic novel, War of Streets and Houses, reflects on the protests and her own place in the city’s power structure.

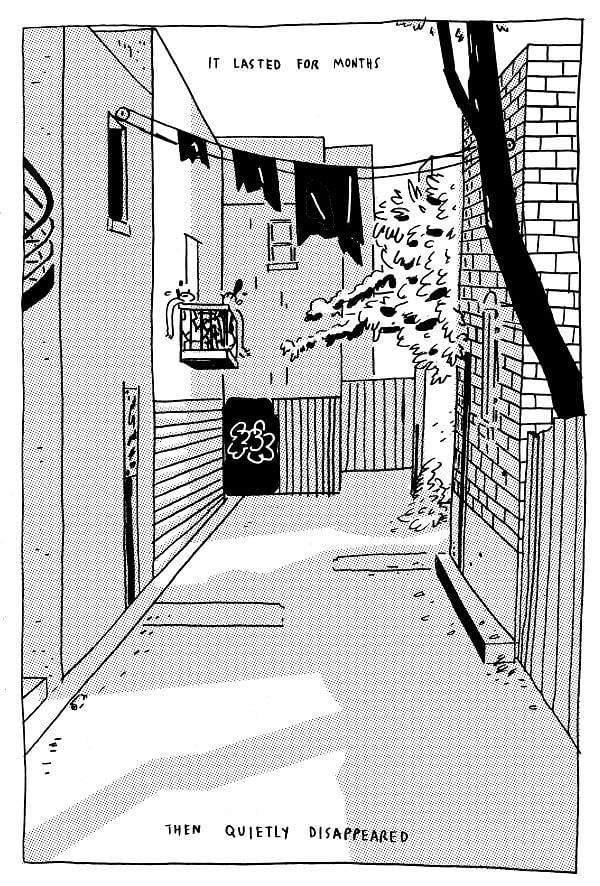

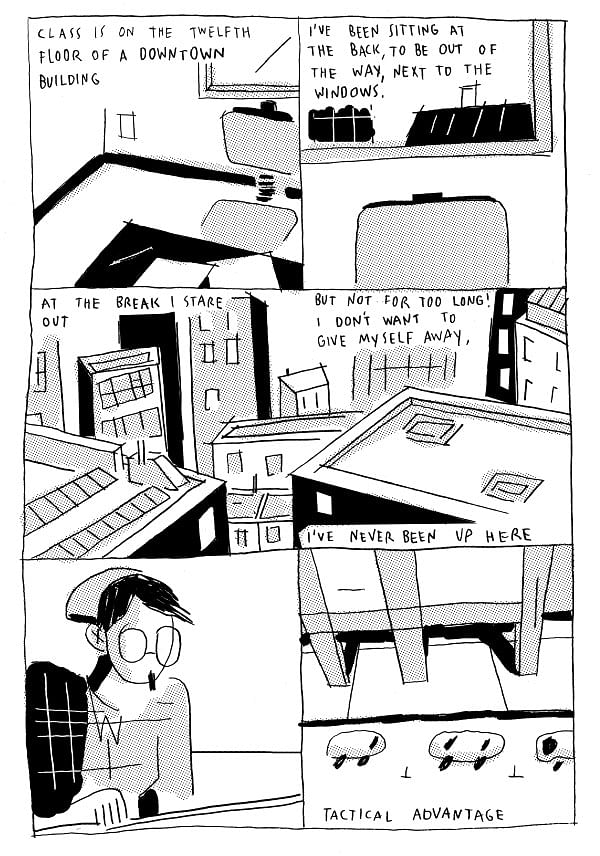

The action of the novel is drawn with cleanly stylized lines in black, white and grays, beginning with the student union’s call for a walkout, and following Yanow’s experience in the strikes and their aftermath. The story is highly personal and at some points reads like a memoir, when Yanow recalls exploring the forests at the borders of her suburban childhood home. Taking its name from a 19th century French military pamphlet, explaining how to conquer the narrow streets of North African cities, War of Streets and Houses is a graceful story of city life as a constant negotiation of power.

Rather than excerpt a single piece of the graphic novel, we asked Yanow about War of Streets and Houses through email, and are featuring her interview alongside selected scenes from the novel. Currently, Yanow is drawing comics at La Maison de la Bande Dessinee in Montreal.

How did you first start making comics?

I started making comics as a very young kid. I started reading when I was four or five, and I read newspaper comics whenever we had them. I particularly loved Calvin and Hobbes. My dad was always very vocal about liking newspaper strips; he would read Watterson's strip, but also comics that I really didn't understand the appeal of, like Prince Valiant. My grandmother on my mom's side also used to mail me clippings of newspaper comics she thought were noteworthy. My mom has a habit of doodling, and my dad is a contractor, so he draws up plans sometimes and writes everything in All Caps – just like a cartoonist! When I was five or six I would draw comics using other people's characters, and then eventually creating characters that closely resembled the strips I liked. Around ten or eleven I stopped making comics, but continued to draw, and didn't really draw them consistently again until University.

Describe the research process leading up to writing and drawing War of Streets and Houses.

The springboard was my participation in the Montreal student strike of 2012. Physically being present in these downtown spaces while the police were using crowd control tactics and mass arresting protestors brought up a lot of questions for me; questions about the efficacy of those spaces for controlling popular revolt. To begin researching, I turned to Nasrin Himada, a PhD at Concordia University in Montreal, whose course "Militarism in the City" gave me a great deal of academic resources and pointed me towards more of my own research. I also read other accounts of the strike, and particularly liked a book called "On s'en câlisse," from the Collectif de Débrayage. It's in French; it begins its analysis of the student strike with an explanation of the physical landscape of Quebec, and theories about how that shapes ways of life here.

Did making War of Streets and Houses change your experience in Montreal, and in cities overall?

It did in that it confirmed certain suspicions I had about the history of urban planning in cities. It was important for me to learn some of that history, if only to tell myself Comics can mimic and incorporate architectural drawing in a way that creates a nice internal logic for talking about space."Your discomfort in these spaces is not completely irrational." Now that I have a better understanding of it, in some ways, I feel more comfortable. Perhaps that's a false sense of security, but I think that understanding is a good step towards making change.

How do comics communicate the built environment in ways that other media can’t?

Western architecture is drawn before being built, and often plans for cities are constructed with grids. Comics rely on grids to create rhythm, and they're usually made with drawings. Comics can mimic and incorporate architectural drawing in a way that creates a nice internal logic for talking about space.

Growing up in rural suburbs, how has your understanding of the spaces between civilization and nature changed since then?

I think now I understand that the concept of "nature" wouldn't exist without the concept of "civilization." Growing up in Northern California, there were a lot of "Back the Land" folks, as well as primitivist and New Age tendencies, that saw the city as a totally destructive force. I've had some sympathy to that, and I feel very lucky to have grown up where I did, but I don't think that rural suburban life is a more "pure" way of living than the city. The spaces between rely on the ends of the spectrum, and the city is much more efficient in a lot of ways.

Towards the end of the story, the narrator returns to nature, but it doesn’t seem to provide the same peace of mind it did before. How did you want the novel's resolution to feel?

I didn't want to wrap things up in a nice pretty package. In one draft I was a little too self defeating: I had a spread near the end that expressed a sentiment like, "Maybe none of this matters!" And my editor said, "You might be depressed about what you've found, but it doesn't mean that none of what you've said matters."

I try to be optimistic. But since I'm trying not to be prescriptive, it's hard for me to say, "Go forth and implement my plan!" The exciting part happens when people say, "I hadn't thought I wanted to show that there was something a little more sinister in the history of urban planning.about things this way." Just getting gears to turn. That creates hope for me.

Regarding the narrator's caution towards engaging in outright protest, for fear of personal safety, do you think this is due to the physical space of activism? Do you think Montreal is a good, or safe, city for protesters?

The police in Montreal are very militarized, and that's certainly a part of the fear. In recent history they have taken a liking to conducting mass arrests via "kettling." Some parts of the city make protest safer: when there are short blocks, alleyways and small passages, there are many escape routes for avoiding a kettle (in Montreal, a $675 fine comes along with the obligatory holding period). Long blocks have proved to be advantageous to police for kettling. The way these spaces are designed, often whomever has larger numbers has an easy upper hand.

Has there been any feedback from the architecture or urbanism community about the comic?

There has been some positive feedback from the architecture community and it's incredibly flattering! I don't feel like what I'm saying is especially new or cutting edge, but I do think that I'm saying it in a different way, and it's nice to be affirmed that there is value in that.

Who do you most hope will read War of Streets and Houses?

I'm very excited for professional practitioners or students in urban planning and architecture to read it, but I wrote it mostly for my friends and other folks who participated in the strike, and who participate in protest generally. I wanted to make something to combat the narrative that protestors are guilty of initiating violence and provoking the State into repressive tactics. I wanted to show that there was something a little more sinister in the history of urban planning.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Sophie Yanow's War of Streets and Houses.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.