One:Twelve, the student-run journal from the Knowlton School of Architecture, is both a collaborative and expansive effort. Jointly managed across the school’s architecture, landscape architecture, and city planning departments, the journal's content is culled from Knowlton and beyond, with writing from other universities, disciplines and professions.

The journal's seventh issue, Black and White, considers the abilities of opposites, to sometimes clarify and other times confuse. As the iconic opposites, “Black and White” can be used to mark distinctions in stark relief, but when combined they can confuse and obscure details in a swath of gray. Our featured article for Screen/Print sees black and white as classic symbols of grime and purity, in the world of early 20th century New York City’s waste management systems. Ian Mackay’s “The Black Box” looks at a turning point in the city’s attitude towards garbage, when machines were replaced by men in gleaming white uniforms handling push brooms.

Black Box/White Wings: A colorful moment in the history of trash

By Ian Mackay

The Black Box

In the lexicon of science and engineering, a “black box” is a device, system, or object that is essentially opaque: it can be viewed in terms of its inputs and outputs, but its inner workings remain unknown. Urban theorists use this concept to explain how people in western cities tend to understand the infrastructural networks that serve and sustain them:

"Indeed, when infrastructure networks work best, and succeed in reaching mass adoption as the basis for styles of urban life, they tend to become progressively both more “ordinary” and less noticed… In the language of the sociology of technology, such infrastructures become “black boxed” by their users (Graham 6)."

Consider the infrastructure of municipal solid waste management. Few individuals put much thought into what happens to their trash after they drop it in a garbage can and roll it to the curb. From there it might be buried, burned, recycled, or reused. But the man at the curb has little insight into the sophisticated technologies that collect, transport, and distribute it—or the real conditions of its final resting place. And why should he? Nothing compels him to care much about it. As long as it doesn’t pile up and cause him problems, he’s happy to leave its management to the sanitary engineers and technicians who make a living of it.

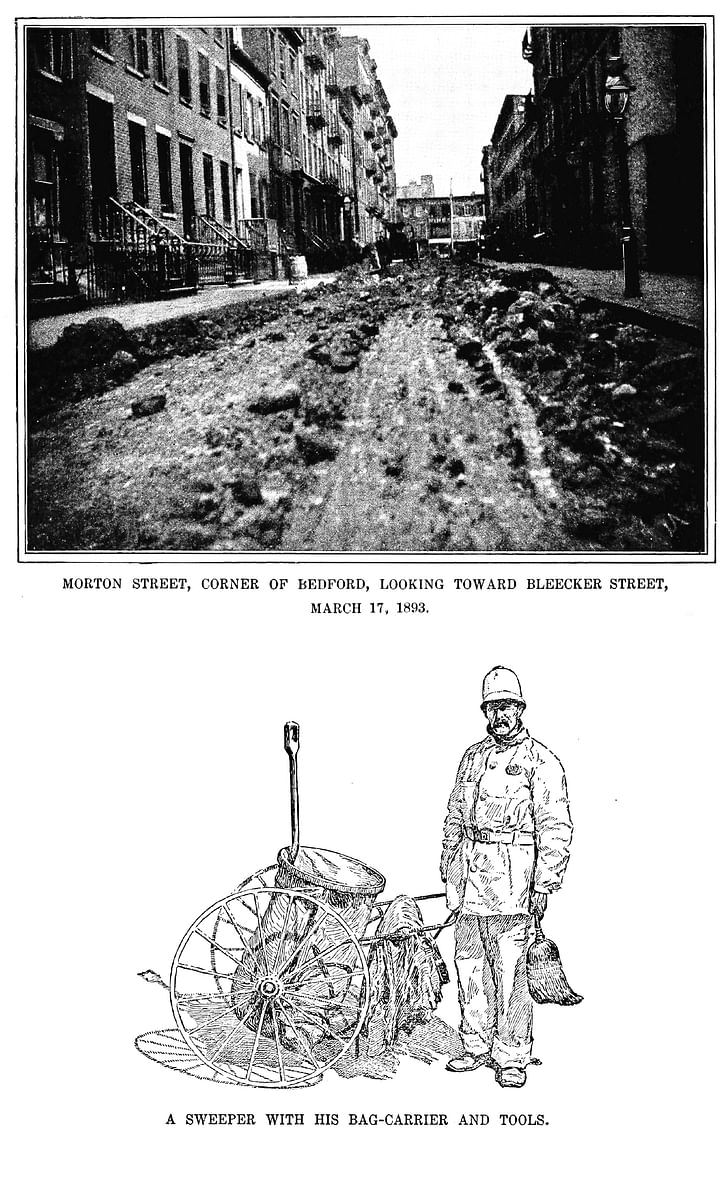

Before the Black Box: Black Streets

Municipal solid waste was not always black boxed. There was a time when one could not escape it. New York City’s legislature created a Department of Street Cleaning in 1881. But it was riddled with the corruption of Tammany Hall, and evidence of its failings was everywhere:

"Before 1895 the streets [of New York City] were almost universally in a filthy state. In wet weather they were covered with slime, and in dry weather the air was filled with dust. Artificial sprinkling in summer converted this dust into mud, and the drying winds changed They were the objects of ridicule and scorn, and they knew it. They did such work as they were compelled to do, and, as a rule, they did no more.the mud to powder. Rubbish of all kinds, garbage, and ashes lay neglected in the streets, and in the hot weather the city stank with the emanations of putrefying organic matter. It was not always possible to see the pavement, because of the dirt that covered it… Dirty paper was prevalent everywhere, and black rottenness was seen and smelled on every hand (Waring 13)."

The department’s street sweepers were a rag tag bunch of men clad in brownish suits and grayish-brown caps that matched the muck of the streets around them: “they were the objects of ridicule and scorn, and they knew it. They did such work as they were compelled to do, and, as a rule, they did no more. Nominally, they wore a uniform, but they were not distinguished by it” (Waring 15).

The first commissioner of the department noted that merchants and householders seemed blind to the city’s attempts to clean the streets, and that their ignorance hampered his efforts:

"It has frequently happened that the street-sweeping machine has passed down the street, and before it has reached the nearest corner men and women have been seen deliberately emptying receptacles full of refuse and rubbish from their shops or residences upon the pavements just swept. Handbills and other printed matter distributed to pedestrians were thrown on the sidewalk or street… Such things were not done, perhaps, because the offenders had resolved to be blameworthy and contemptuous, but because they were imbued with the spirit of indifference to the public welfare and had long been accustomed to do such things without fear of the law (Waring 2)."

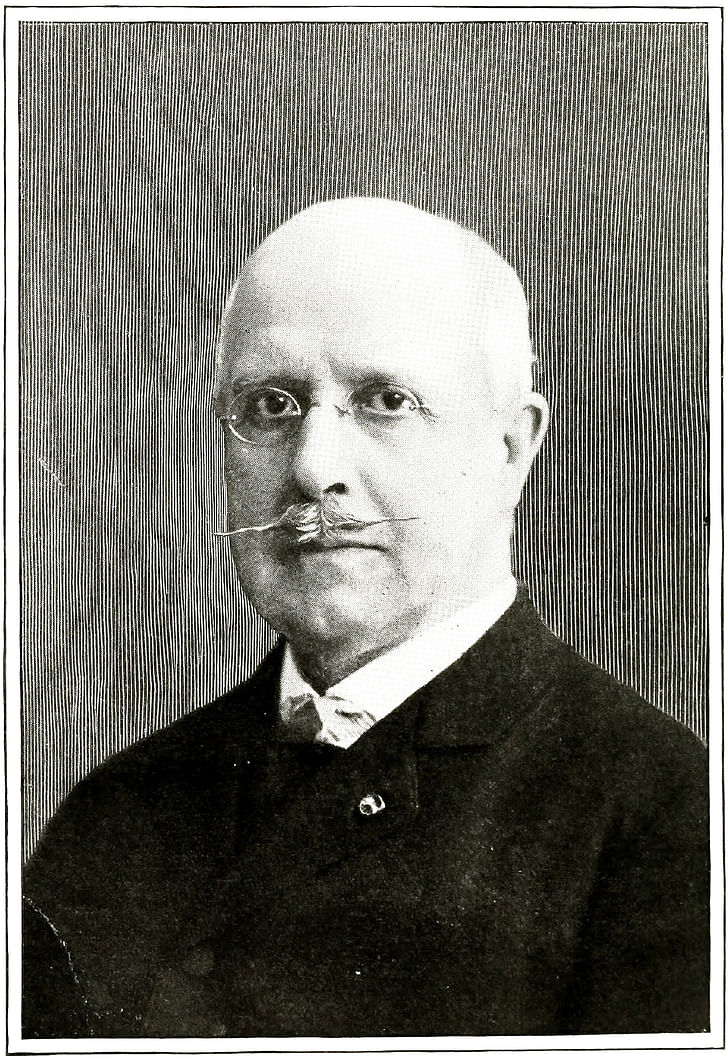

Enter the Colonel

Appointed Street Cleaning Commissioner in 1895 by the newly elected Mayor William L. Strong, Colonel George E. Waring, Jr. was charged with reforming the corrupt department and ensuring that it functioned properly. His qualifications included the design of the separate sewer system that helped rid Memphis of yellow fever and a stint as the drainage engineer of Central Park.

Waring brought a healthy dose of gusto to the Commissioner’s desk: he was known as “an unabashed self-promoter” with a taste for flamboyance (Melosi 157). Before the Civil War, he assisted Central Park’s first engineer, Egbert Ludvickus Viele. To the great annoyance of his superior, Waring took to trotting his splendid pair of white horses around the park roads each morning (Benjamin 162). His subsequent service in the Civil War only heightened his taste for military pomp and spectacle. He attained the rank of colonel, which he maintained as an honorific throughout his life.

The ‘White Wings’ are by no means white angels, but they are a splendid body of men, a body on which the people of New York can depend for any needed service, without regard to hours or personal comfort.As commissioner, Waring introduced a completely new and unprecedented program. It included a number of the best methods that had been attempted piecemeal in other cities around the nation: primary separation of trash at the household level (garbage*, rubbish, and ashes); the first municipal rubbish-sorting plant; a garbage reduction plant on Barren Island; and a land reclamation program on Rikers Island. But before implementing any of these technological reforms, Waring put on a show.

White Wings

The ‘White Wings’ are by no means white angels, but they are a splendid body of men, a body on which the people of New York can depend for any needed service, without regard to hours or personal comfort (Waring 21).

Before Waring’s appointment, street sweeping was done mostly by machines and almost universally in the black of night. The colonel changed that. Under his command, street sweeping was done entirely by hand during daylight hours. He crafted a new corps of sweepers especially for the task: the White Wings. Unlike their dun-colored predecessors, Waring’s men were outfitted in brilliant white suits topped with white pith helmets. They deposited their sweepings in white, wheeled buckets designed by the colonel’s wife, Emily.

The whiteness of the corps was in some ways impractical for its cleaning duties (Waring 39), but that was exactly the point. Arrayed against the grimy blackness of the streets, they would shine as beacons of sanitation—allied with white-clad doctors and nurses in the fight for good health. At the same moment in domestic architecture, white porcelain fixtures were emerging from formerly dark, wooden enclosures in kitchens and bathrooms (Lupton, Miller 26). The hard, white surfaces rendered dust and grime immediately visible, prompting an urge to clean them. Whiteness thus invited a sanitary paranoia that was hard to ignore in either the private or public realm: “it cannot be doubted that in New York the fact that the sweepers stare the public in the face in every street has had much effect in securing popular approbation and assistance” (Waring 134).

To energize and educate those human resources, he drew from experience: people like a good show, and, what’s more, they remember it.But Waring was not content with approbation—he demanded celebration. One of his first actions as commissioner was to orchestrate a parade of the men in their new gear down Fifth Avenue. The colonel, of course, led the charge, resplendent on a white stallion (Miller 76). The mayor viewed such showy displays as a distraction from the real work of the department. He gave Waring a public reprimand only six weeks into the job for failing to quickly clear the filthy snow that obstructed city streets (Miller 76).

The mayor was mistaken. Waring’s antics were not a sideshow. The public spectacle he created with the White Wings was crucial to the effectiveness of the rest his program. By successfully branding the newly clean streets with the strong, simple image of the White Wings, Waring made it easy for the citizenry and the local papers to extend their enthusiasm to his efforts to develop solutions to more complex problems. The most pressing was the question of how to ultimately dispose of trash. Waring’s popularity allowed him room to experiment with both new and old techniques like rubbish-sorting, garbage reduction, and land reclamation.

Waring’s genius lay in his recognition that the infrastructure of municipal waste management was abundant in humanity: it included not only its workers, but potentially the entire body of trash-producing citizenry. To energize and educate those human resources, he drew from experience: people like a good show, and, what’s more, they remember it.

Their white uniforms, once so derided, have been a great help to them, and they know it; and the recognition of the people has done still more for them. Indeed, the parade of 1896 marked an era in their history. It introduced them to the prime favor of a public by which, one short year before, they had been contemned [sic]; and the public saw that these men were proud of their positions, were self-respecting, and were the object of pride on the part of their friends and relatives who clustered along their line of march (Waring 20).

The colonel’s vision was catholic, reaching even the city’s children. He drafted them into the ranks of sanitarians with the creation of Juvenile Street Cleaning Leagues. Waring decided that children of immigrant families could educate their parents more effectively than his Arrayed against the grimy blackness of the streets, they would shine as beacons of sanitation—allied with white-clad doctors and nurses in the fight for good health.inspectors. Every child was encouraged to speak to adults and other children about keeping the city “tidy and neat” and earn a badge by reporting “the number of bonfires which he has succeeded in stopping; the number of skins which he has kicked into the gutter from the sidewalk; the number of papers he has induced others to put in the barrel instead of on the pavement; and various things of a similar nature” (Waring 180). Many children seemed to respond quite enthusiastically.

Post 1898: Towards a Black Box

Waring’s tenure as Street-Cleaning Commissioner ended in 1898, and he died later that year. He was killed, ironically, by yellow fever—the disease he had worked to eradicate in Memphis. By that time, his work in New York had generated considerable local and national attention and similar programs were developed in numerous cities. Juvenile street cleaning clubs were reported in Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Pittsburg, Utica, and Denver (Waring 179).

After Waring, municipal engineers became the dominant figures in refuse collection and disposal. But like the mayor who reprimanded Waring after his first parade, they misjudged the value of public spectacle in the development of successful municipal infrastructure:

"While many of Waring’s successors avoided his Barnum-like penchant for self-promotion, few showed the dramatic flair for rousing the public to the sanitation crusade, and thus too easily dismissed the value of citizen participation. Moreso than Waring, the municipal engineers who followed him into city service placed increasing faith in technical solutions to the “garbage problem” (Melosi 194)."

Thus began the trudge towards the black box. Sanitary engineers tested and developed new practices in the ensuing decades, but they were focused on finding “a single, technical panacea” to rid the city of its solid waste (Melosi 263). The invention of the modern sanitary landfill in the 1930s came closest to realizing that goal. It became the first universally accepted disposal option in the US; after World War II, many cities adopted its use. The basic principle of the sanitary landfill is to dispose of all forms of waste simultaneously, burying them beneath layers of earth. Usually located at the margins of urbanity, the sanitary landfill is quite literally a black box. Most Americans are happy to keep a lid on it. Urban theorist Stephen Graham notes the implications of that mindset:

"Cultures of normalized and taken-for-granted infrastructure use sustain widespread assumptions that urban infrastructure is somehow a material and utterly fixed assemblage of hard technologies embedded stably in pace, and which is characterized by perfect order, completeness immanence, and internal homogeneity rather than leaky, partial, and heterogeneous entities (Graham 8)."

Colonel Waring’s short stint in New York City offers an alternative vision. He produced a moment of intense imagination in the development of urban infrastructures because he understood that they extend beyond their engineered technologies to include human users and servicers. They are not merely technical, they are not stable, they are not apolitical, and they do not have to be boring.

*At that time, the term garbage described organic waste like food scraps, whereas rubbish described more stable castoffs like old shoes.

Resources

Graham, Stephen. Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Waring, George E. Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City's Wastes Methods and Results and the Effect upon Public Health, Public Morals, and Municipal Prosperity. New York: Doubleday & McClure, 1899.

Melosi, Martin V. The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

Miller, Benjamin. Fat of the Land: Garbage in New York: The Last Two Hundred Years. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2000.

Lupton, Ellen, Miller, J. Abbott. MIT List Visual Arts Center. The Bathroom, the Kitchen and the Aesthetics of Waste: A Process of Elimination. Cambridge, Mass.; New York: MIT List Visual Arts Center; Distributed by Princeton Architectural Press, 1992.

Also found in One:Twelve's Black and White:

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured One:Twelve's Black and White.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.