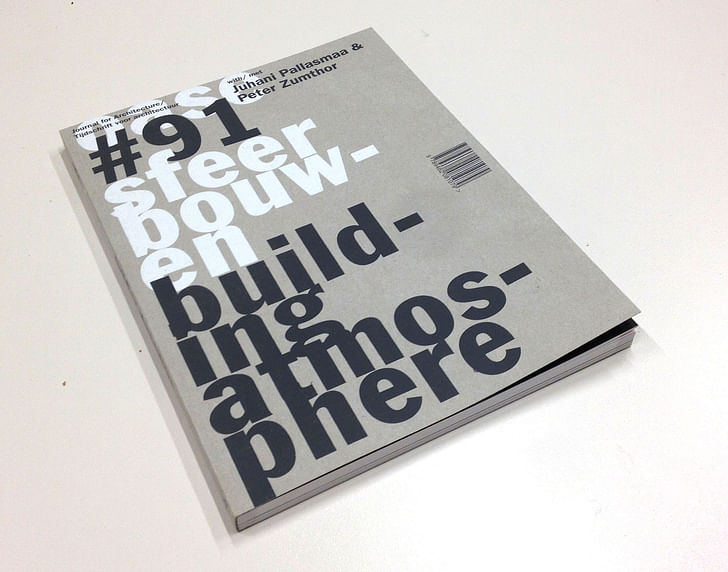

OASE runs on the steam of academic discourse. The peer-reviewed architecture journal is based in the Netherlands, but keeps a high standard of international contributions, most of whom have a foot in both camps of design practice and academia. The journal is published twice a year, our Screen/Print featuring the second issue of 2013, OASE #91: "Building Atmosphere".

Rather than honing an issue down to a fine point, each issue of OASE unfolds a single theme into related cultural and historical topics that emphasize the impact of the architectural discussion, printed in both Dutch and English. We’re focusing on a piece by Finnish architect and architectural theorist, Juhani Pallasmaa, that takes a critical and introspective look at the way an individual “consumes” architecture, through the body’s senses.

Pallasmaa runs Arkkitehtitoimisto Juhani Pallasmaa KY in Helsinki, and also serves as the Plym Professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He is well known and read for his theory on how visual stimuli have come to dominate the evaluation of architecture -- an ocularcentricism that is common to the majority of art forms, and often a major criticism of modern architecture’s priorities. In his “Orchestrating Architecture” essay for OASE, he reconsiders his interpretation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings and their remarkably haptic atmospheres, inspired by a stay at Wright’s Taliesin West studio.

Orchestrating Architecture: Atmosphere in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Buildings

Juhani Pallasmaa

Modernity at large has been more interested in form than feeling, surface than materiality and texture, focused imagery than enveloping space, shape than ambience and atmosphere. Yet, there are modern and contemporary architects whose spaces have an atmospheric character, that one feels as a haptic embrace on one’s body rather than as a mere external retinal image. These atmospheric spaces engage us and make us participants in the space instead of remaining as inactive onlookers. The atmospheric architects of modernity, most notably Alvar Aalto, Gunnar Asplund, Hans Scharoun and Sigurd Lewerentz, seem to be part of the Other Tradition of Modern Architecture, to quote the title of Colin St John Wilson’s book. Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings, also, project a tactile and embracing character that is felt through the body and skin as much as by the eye. All the way from his early works, such as the Unity Temple, the Robbie House and the Imperial Hotel (in photographs this dismantled building appears exceptionally textural and tactile, like a man-made stalactite cavern), to his modern masterworks, the Fallingwater House and Johnson Wax Company Building, his buildings project a sensual presence and atmosphere. These spaces could be called haptic and ‘dense’ spaces, in the sense of the significant role of textural and material stimuli and varied illumination that enhances the tactile realm. The deliberate reduction of scale – a miniaturisation of sorts – adds to the experience of nearness and intimacy.

Wright, in fact, seemed to be quite conscious of the importance of atmospheres in architecture. ‘Whether people are fully conscious of this or not, they actually derive countenance and sustenance (Italics by FLW) from the “atmosphere” of things they live in and with,’ he writes. The fact that he suggests an unconscious impact is also significant, as ambiences and feelings are usually registered subconsciously as merged multisensory and unfocused experiences. Due to this subliminal nature, immateriality and formlessness of the atmospheric experience, it is difficult to identify, analyse and theorise, not to speak of deliberately aiming at in the design process. Architectural atmosphere is thus bound to be a reflection of the designer’s synthetic existential sense, or sensitive feeling for being, which fuses all the sense stimuli into a singular embodied experience.

Our atmospheric sensibility could well be named as the sixth human sense.Altogether, the most essential architectural qualities seem to arise instinctively from the designer’s sense of his/her body rather than conscious and intellectually identified objectives. In addition to – or as part of – his intuitive grasp of the significance of atmospheres, Wright was also instinctively sensitive to other architectural qualities, such as the reading of the essence of the landscape, its dynamism, rhythm, materiality, history and hidden primordial narratives. In his book The Wright Space: Pattern and Meaning in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Houses, Grant Hildebrandt studied Wright’s extraordinary instinctual understanding of the meaning of the mental polarity of ‘refuge’ and ‘prospect’, the dialectics between a sense of protective enclosure and safe and comforting intimacy on the one hand, and an open, overall vista across the landscape or setting on the other, which provides a means of anticipation and control of the environment. As ecological psychologist Jay Appleton has suggested, these are bio-historically acquired instinctual and unconscious environmental reactions, brought about by processes of natural selection. Wright’s houses provide this duality of a protective centre and an open peripheral vista, that is they seem to simulate the environmental conditions of the early human development on the African savannah, and consequently, they provide a strong sense of protection and well-being even today.

Recently I had the opportunity of staying five months at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West desert studio in Arizona, built in 1937-1938 as an ‘architectural sketch’, as the architect characterises the project, and kept expanding and altering it until his death. Having myself developed a deep interest in architectural atmospheres, the stay offered a unique possibility to sense and identify the design strategies of this great architectural talent. My experiences and observations confirmed my assumption that atmospheres could be the most comprehensive and integrated of architectural qualities, but connected so deeply and complexly with our awareness, sense of self, and bio-cultural instinctual reactions that they can hardly be conceptualised and verbalised. Our atmospheric sensibility could well be named as the sixth human sense. This difficulty is parallel to the fact that our emotions, reactions, moods and Sound and music are omnidirectional and embracing experiences in contrast to the directional and externalising sight.behaviour are fundamentally conditioned by our unconscious motifs, which we can hardly identify due to their essence outside of consciousness. Another problem for an analytic effort arises from the fusion of opposites and internal contradictions characteristic of all profound works of art and architecture.

The Taliesin West complex rests in its Sonoran desert setting as if it had been there before the landscape. Architecture arises from the land and landscape, but at the same time it gives the setting new readings and meanings. These architectural structures seem to mediate images and vibrations of some primordial and mythical origins. Wright’s use of ‘desert concrete’ (desert stones and boulders set in the formwork with viscous concrete to appear simultaneously as a masonry wall and cast structure) echoes the desert floor and terrain, whereas the architectural geometries evoke distant geological processes and early Native American cosmological structures. The compound actually contains several ancient petroglyphs, while the architectural ornamentation in Wright’s buildings suggests Native American motifs. The buildings fuse opposite images, such as suggestions of ruins and Utopia, togetherness and solitude, weight and lightness, gravity and flight, the impenetrable darkness of shadows and the purifying light filtered through surfaces of stretched white canvas. Further polarities keep coming to the observer’s mind: a cave and a kite, agelessness and novelty, uniqueness and tradition, recklessness and safety.

The domestication of fire has a central role in the development of human culture and psyche. Vitruvius connects the beginnings of architecture to the domestication of fire. Recent studies in the origins of language also associate the beginnings of linguistic communication with the taming of fire. Fire has been the focal point of human societies for tens of thousands of years, and the experience of gathering around a fire continues to evoke a sense of centre, safety and togetherness. Besides, staring at flames is one of the strongest enticements for fantasy, dreaming and imagination. Leonardo advised artists to stare at a crumbling wall in order to achieve a state of inspiration, but, as Gaston Bachelard has suggested in his books on imagination, flames and their opposite, water, are the true stimulants for imagination; in the philosopher’s view, they are the two truly poetising substances. Not surprisingly, Wright also recognised the atmospheric and imaginative power of water and integrated water in most of his projects.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses always centre on a fireplace, or a cluster of them. At the Taliesin West there are numerous fireplaces, even in the studios and other work spaces, dining rooms and outdoor terraces. The fireplaces are used to provide heat for the rooms, which originally did not even have glass to close the openings, but more importantly, the huge fireplaces, arising directly from the floor, large enough for a person to enter, project an extraordinary sense of warmth and welcoming, both physical and psychological. Besides, they create points of focus and images of gathering together. Sound and music are omnidirectional and embracing experiences in contrast to the directional and externalising sight. In Wright’s pedagogic thinking and life, music had a central role (there are nearly ten different pianos at Taliesin West alone), and this seems inevitable for someone interested in highly emotive and moving atmospheres.

‘Natural architecture’ arises from our modes of being human, being part of nature and culture at the same time, and from observing life and human behaviour itselfHere at Taliesin West, nature is the setting, but it also literally takes over the human constructions, suggesting temporal duration, and eventual decay. Wright’s favourite colour, Cherokee red, blends concrete floors as well as steel and wood structures with the colours of the desert and the sunset. Wright often made the remark that there are no continuous and hard lines in the desert; the lines of the desert are broken and ‘dotted’. At Taliesin West, the eave lines are broken by small ornamental cubic blocks to echo the thorny and prickly edges of the Sonoran plants. When thinking of Wright’s way of blending buildings in the landscape, I want to use the word ‘orchestration’ to emphasise his intuitive manner of integration through similarity and contrast into a unified, but dynamic unity, as in musical counterpoint.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture is ‘a natural architecture’, not primarily in any biomorphic or mimetic sense, or due to Wright’s own use of the notion of ‘organic architecture’, but in its deep grasp of the genetically derived ways in which we are in constant dialogue with our settings and domicile. ‘Natural architecture’ arises from our modes of being human, being part of nature and culture at the same time, and from observing life and human behaviour itself, not from theoretical constructs or rationalisations. A deliberate and conscious idea of fusing the abstract geometries of neoplasticism and geometric motifs of Native American tradition, images of Meso-American ruins and a spiritualist camp, universalism and locality, cosmos and an intense sense of place – all characteristics of Taliesin West – would surely be doomed to failure. Only a sensitive mind that has internalised all of this and much more can succeed in this impossible task of orchestration. As Rainer Maria Rilke tells us, verses in poetry are not mere feelings; they are experiences. But these experiences have to be forgotten and turned into the blood in the poet’s veins before they can give birth to the first line of verse.

Editors of issue #91, Building Atmosphere: Klaske Havik, Hans Teerds, Gus Tielens

Guest editors: Juhani Pallasmaa and Peter Zumthor

Also featured in issue #91, Building Atmosphere:

Editors of OASE:

Design: Karel Martens, Aagie Martens, Werkplaats Tyopgrafie

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we’re featuring OASE #91: Building Atmosphere.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.