Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

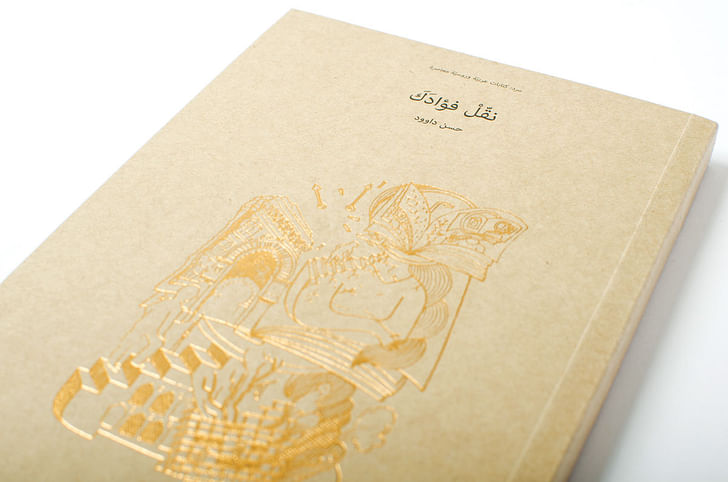

For this issue, we’re featuring Portal 9's Fiction: Contemporary Arabic and Russian Pursuits.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

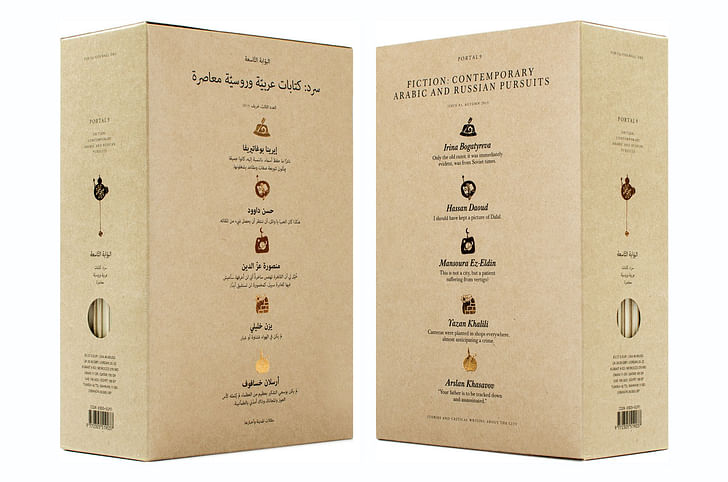

Published twice yearly out of Beirut, Lebanon, Portal 9 puts out a mix of creative and critical urbanism writing. Unique for an architecture publication, the journal is neither academic offshoot nor personal pet project, but an initiative from a post-war redevelopment company, Solidere. Beirut was severely damaged by the end of the country’s civil war, and in 1994 the government created Solidere to rebuild the city’s Central District, overseeing urban planning processes and real estate development. Portal 9 is part of that effort, to strengthen a cultural identity in writing alongside an urban one.

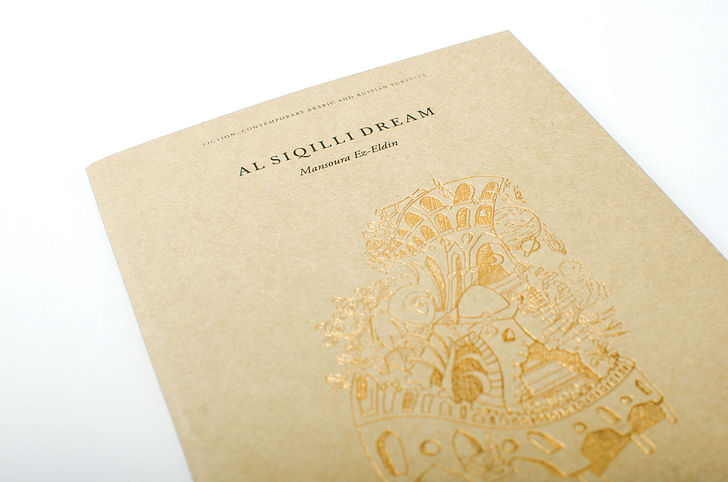

Released in both Arabic and English versions, each issue of Portal 9 proposes a single theme for interpretation throughout and beyond the Middle East. The journal’s most recent issue, “Fiction: Contemporary Arabic and Russian Pursuits”, focuses on the subtle and at times fragile nature of personal narrative, and how human experience condenses into history. Screen/Print is featuring a short story from “Fiction” by Egyptian writer Mansoura Ez-Eldin, about a journalist sifting through fact and folklore in Cairo.

Visit Portal 9 for more information. You can purchase “Fiction: Contemporary Arabic and Russian Pursuits” here.

“Al Siqilli Dream”

Story by Mansoura Ez-Eldin

Arabic-to-English translation by Meris Lutz

Adam Khalifa was sitting at a table tucked away in the corner of Groppi Garden on Adli Street when I met him. He sipped his coffee with conspicuous relish, then fixed his eyes on a nearby tree as if he could see something there no one else could. I called to him, but he did not answer, so I sat across from him, waiting for his wandering mind to return.

By the light of day, I found he was smaller than I had thought, his hair completely gray, but his face retained some youthful vigor for a man in his sixties. When he finally turned to face me, it was to ask if I had found a publisher for his brother’s book. I had forgotten about the whole thing and was unsure where I had even put the book amid the chaos of my office. I told him that I had given it to a friend who works in a well-known publishing house and would inform me of their decision soon. He pressed his lips into an expression of annoyance as if he had been expecting me to open my bag and pull out a freshly printed copy swaddled in gift wrap.

The whimsy he displayed during our first encounter encouraged me to tell him about what had happened to me after I left his office two days ago. He listened, his face betraying no expression, then asked: “A winding street and buildings like fortresses?!”

I nodded, and he went back to gazing at the tree. Then he told me he had never heard such a thing. It did not really matter to me either way, having convinced myself that the whole thing was a product of an overworked mind. I had spent two hours on Qasr Al Nil the day before, and with every step, the shadows of the dim, winding road retreated until they faded.

Without meaning to, she had pointed me toward my method for studying architecture: emotions and oral history in all its infinitesimal details. To my surprise, his answers to my questions about Cairo and its architecture were very different from our first meeting. He spoke at length about the Cairo of Khedive Ismail, a city “yearning to catch up to the rest of the civilized world,” about the neighborhood of Heliopolis, where he spent his childhood and youth, and about his project to double the number of green spaces in greater Cairo. For a moment, I doubted whether he was the same person I’d spoken with before. He was more grounded. He made no mention of the capital of the Fatimids, but when I asked him about his future plans, he said he dreamed of building another version of Jawhar Al Siqilli’s Cairo using the same building materials and design, insisting that such an undertaking would attract global attention.

* * *

That night, I dreamed of the burning papers falling from the Ramses Hilton. They glittered and blazed far more vividly than they had in reality. I stopped, amazed, and lifted my face to watch the fragments of fire against the dark. From afar, I saw Adam Khalifa looking out from one of the windows, throwing more papers that lit up like shooting stars before extinguishing as they hit the ground. A few moments later, I found myself in one of the hotel rooms, looking for him. All I remember was that the room was tidy and empty and looked like a room I had seen in an American movie. An open door next to a full-length mirror on the wall brought me into a narrow basement, its walls polished and glittering like jewels. From there, I moved into a street whose buildings resembled castles. I walked confidently, as if I were in my own house. When I reached the end, I saw Al Attour Street, where I lived for five years, and the familiar sensation of asphyxiation returned. Al Attour, or “perfume street,” was anything but.

As soon as I entered the street, the sky was all but lost from view. The stench from the poultry shop was overwhelming: I used to sprint by in order to escape the smell. Nearby, Faisal Street intersected with Al Attour Street, leading away only to turn back around and empty back into it. The two thoroughfares entwined and overlapped, more like coiled intestines than the founding streets of a quarter built for human habitation. For five years, I was haunted by the feeling that I was living underground, with neither sky nor wind nor light. I never felt that I was truly in the world of the living until I left the haphazardness of Faisal Street. I used to buy my dairy products from Al Khair wa Al Bakara (Goodness and Blessing), my groceries from Al Haramein Al Sharifein (Mecca and Medina), and my medicine from Yathrib Pharmacy, as if I had traveled back in time to the seventh century.

In my dream, I was more generous toward Al Attour Street. In fact, it was not as hideous as I imagined; or rather, its ugliness was picturesque, the dream glossing over its flaws. Adam Khalifa was standing in front of Yathrib Pharmacy, explaining to an excited crowd his plan to build a “new Cairo.” With every word, a piece of his coveted city would materialize before my eyes. I saw a band of raucous musicians encircling a huge palace surrounded by a high wall next to a square. I awoke with the melody ringing in my head.

My city is that whose map is imprinted on my mind and whose alleyways haunt my dreams. I found a text message from Adam Khalifa informing me that he had e-mailed me a short passage he wanted to include in the interview. I was still half asleep as I read what he had written:

My city is that whose map is imprinted on my mind and whose alleyways haunt my dreams. It is that which I carry with me wherever I go and the standard by which I judge all my temporary cities. Wherever I went, Fatimid Cairo remained a lifelong obsession of mine. It is the reference for all the places I traveled as if it were the past of all these places, how the city thought of itself. Al Maaz Street is the nucleus of the world, as far as I am concerned, the locus from which all other streets branch out and every neighborhood and nation scattered accordingly.

I did not realize this until I left to study in Germany. There, in silent Munich, I sought out the bustle of Cairo. There, the soundtrack of my life had faded away. I nearly went mad, as if the noise were the only thing keeping me together, preventing me from turning into dust to be carried away by the wind of my ancient city. I realized I had been cured of my dependence on chaos only when I found myself annoyed to be awakened by the sound of a speeding car, which was quickly swallowed by the silence of the night.

Just before I left Egypt, my teacher told me he had studied in the same university right after the war, when all of Germany was one giant construction site as they began to rebuild what had been destroyed. I was envious and wished I could go back thirty years and accompany him, see what he had seen. When I left, I took his stories with me. I began delving into the layers of architecture, tracing the fingerprints of historical shifts, which only increased my longing for “my Cairo.”

But cities are not just piles of stone.

When I think of Munich now, it appears as the beautiful blond woman in the green silk dress who accompanied me on the train to Austria, or perhaps the dress itself. When we crossed the border between Bavaria and Tyrol, my companion was struck by a sudden bout of nostalgia. With childish abandon, she began singing a popular ditty mocking the people of Tyrol, then turned to me and explained that the song was tied to the history of bad blood between the two regions. Without meaning to, she had pointed me toward my method for studying architecture: emotions and oral history in all its infinitesimal details. At that moment, the image of Al Maaz Street appeared in my mind, and I decided to start collecting everything I could find about it from the forgotten tales.

Portal 9 credits:

Co-Founder, Editor-in-Chief: Fadi Tofeili

Co-Founder, Creative Director: Nathalie Elmir

Editor-at-Large: Eyad Houssami

Design: Antoine Ghanem

Production: Dina Boustany, Mario Razzouk, Zeina Naccache

Project Management: Limassol Zok

Financial Management: Sumaya Baroody

Coordination and Distribution: Mohamad Rhaymi

Urbanography Editor: Todd Reisz

Contributing Editor: Hisham Awad

Copy Editors: Tracey Dando, Mohammad Hamdan

Proofreaders: Mohammad Hamdan, Judith Riotto

Cover Art: Hiba Farran

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

A,

Nice to read this, it is a Portal. My collection of Arabic literature is tiny but what I have has this in common: they tend to small personal narratives. Perhaps it is because of the emphasis of the journal or is the small personal narrative a preferred 'type' is Arabic writing?

e

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.