AfterShock is a non-conclusive series that grapples with the impact and responsibility of contemporary architectural design, hoping to instigate dialogues on how to make architecture more accountable.

I recently took a trip through IKEA, on a treasure-hunt of domestic parboiled maturity that would accessorize and enable my transition from college-student to mid-20s professional adult. Marveling at IKEA’s own serpentine pavilion set-up, pushed along on a steady stream of soap trays and closet organizers, I saw up ahead a neat office scene -- perfectly stacked cabinets and drawers in clean pine encased a cozy workspace area, complete with modular bookshelves, laptop desk-space and office chair. As I got closer though, the scene didn’t grow in size as much as the anticipated scale should have allowed -- this was a child’s workspace. I was in a kiddie laptop bunker.

We are effectively experiencing another Market Revolution, not only in the digital/global marketplace, but in our relationship to our jobs. I’m not going to debate the techno-ethics of childrearing, but instead marvel at how workspace design, with the advent of diverse communication media and omnipresent internet access, has become a highly idealistic and curated field of architecture. When (and if) one’s entire profession can be done from anywhere, the choices of how and where to work are nearly limitless. How should work-space be prioritized? The design isn’t meant to optimize physical production or operate static technology, while becoming more rooted in the company’s ideology. While liberating and certainly contentious, the internet’s workspace revolution has no small effect on not just how we work, but our ideas of what being a worker is. We are effectively experiencing another Market Revolution, not only in the digital/global marketplace, but in our relationship to our jobs.

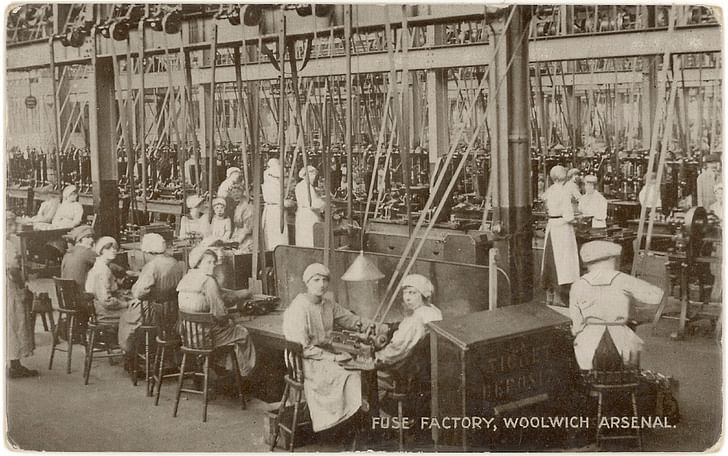

In a trend echoed the world over, labor in early 19th century U.S. shifted from the home to the factory. Thanks to risky, Big Business investments in federal infrastructure efforts, fueled by technological and communication innovations (the telegraph, the Erie Canal, trans-national roads, etc.), the U.S. marketplace was expanding and growing stronger. Stimulated commerce throughout the frontier West, the industrializing North and King Cotton South allowed for increased competition and specialization of goods, and generally stressed out the cottage-industry model of production, where workers assembled goods in their home. Merchants eventually realized that if they moved workers to centralized locations within the factory, they could produce goods more efficiently*.

The serendipity model invests in social collaboration to produce new ideas, rather than designing spaces to maximize an individual’s output. Now that work depended on being in the factories to operate specialized machinery, the worker’s output was dictated by the clock -- not their personal handiwork at the end of the day. This casts the subtle difference between the “maker” and “worker” identities in stark relief -- “making” is a transitive verb, referring to an object (productive!), whereas “working” is a state of being (temporal!). Now, instead of wages being linked to the worker’s “price”, which depended on the quality of their produced goods, pay was based on number of hours in the factory. Workers and their work became more strongly beholden to their employers, and standardized to a timetable. To anyone who has ever fought for overtime-pay, this is an essential paradigm -- and to anyone who has ever rounded out 3-5pm reorganizing old Gmail folders, an outrageous surrender of Jeffersonian rights.

The first Market Revolution made time into the standardized currency, and the workplace adapted to maximize that currency. Workers became units of efficiency, replaceable and commodifiable. Nowadays, workplace design (especially in tech industries) seems to trend towards maximizing something even more abstract and slippery than time: innovation. We've catapulted through the goods-based economy and into a knowledge-based economy. Companies may contract architects to try and design for innovation through a pseudo-scientific alchemy of environmental psychology, ethnographic studies and branding. But it’s also important that the resulting design is marketable, and consistent with the company’s brand.

This may seem like a subtle shift, but coupled with the desk-liberation of cloud-based work, this constant search for innovative potential can make the work-place into an experimental design forum. Despite the immediacy and reliability of communication media, people generally still work better when they are physically gathered, meaning we won’t all work from home quite yet. That physical community is needed for the spontaneous creation of (buzzword alert) “serendipity machines”.

The corporate campuses of many tech companies have embraced the “serendipity machine” model; building workspaces that allow for massive amounts of people to gather together and initiate networks and collaborations spontaneously, while also, say, playing vintage arcade games or while inside a Moon Bounce. As opposed to the “specialize and segregate” model of isolated cubicles, the serendipity model invests in social collaboration to produce new ideas, rather than designing spaces to maximize an individual’s output. Of course there’s balance to be had, in case you aren’t inspired by the sound effects of Joust, so designing space for solitude and focus is also integral. These spaces must coexist naturally but not overlap, to successfully give productive employees “free-range” over their work environment.

That free-range style increasingly resembles a microcosm of the urban environment. Or at least an idealized forum for Jane Jacobs-style “mixed primary uses”, with access to private-public spheres to sharpen focus. Square’s new headquarters in San Francisco covers four floors and includes a restaurant, “wellness center” and floor plans the length of a city block. Apple’s circular “spaceship” second campus in Cupertino certainly approaches city-scale at 2.8 million square feet, for 13,000 employees. But it’s the interior plan specifically that imitates the natural flow of a city, an attempt by corporate culture to capitalize on the architecture of the “third place” -- Ray Oldenburg’s term for a forum, necessarily separate from work or the home, where socializing and thoughts can flow freely.

Critics of the open plan office-panopticon see these designs as unholy unions of private, professional and social spheres**. By trying to make their workplaces into this “third place”, companies end up usurping the first and second spaces altogether, luring their employees into long hours with infinite creature comforts and flexible, homey offices. And in reverence to the “serendipity machine” model, spaces are obsessively managed and observed, almost as laboratories to study how innovation happens. Through technologies provided by the likes of M.I.T.’s Human Dynamics Laboratory, movements and conversations between employees are measured to collect data on worker interaction -- how long did Employee S talk to Employee P? Was their tone impatient? Were they interrupted? -- and then matched against innovation standards. Whether sociometric data will furnish a parametric solution to optimal workplace design is a pretty provocative proposal -- although it could also be remarkably helpful if/when structures become dynamically adaptable to such data, rather than prescriptively mandated. Imagine materials that can morph to keep out sound, or project it; workspaces whose spaces and furniture can transform to optimize community interactions.

Educational institutions and design competitions are already reacting to these trends. The Master in Work Space Design at the IE School of Architecture and Design, which literally backgrounds its webpage with shots of Facebook’s office interior, offers courses in “The Invisible Workplace: Design for How We Work (and Think)”. The top-ranking entries in “The Workplace of the Future” competition imagine an environment synonymous with computing, where matters of mobility are inverted to the conclusion: “rather the computer being our workplace, our workplace becomes the computer.” Influenced by the freedoms afforded by both online education and virtually-located professions, these courses are markers of a sea-change in working culture fueled by the knowledge-economy, designing not only workplaces, but think-spaces.

Critics of the open plan office-panopticon see these designs as unholy unions of private, professional and social spheres. Coupled with a wider variety of work places, advances in technology have also enabled a culture of co-work environments. This generally refers to a place where a diverse collection of workers gather in a cozy and (ideally) mutually beneficial space. Clearly this trend is industry specific, and relies at least as much on individual personalities as it does interior design, but co-work environments have become their own thriving business. Curated office-spaces from the likes of WeWork, Blankspaces, Gangplank and Hera Hub are only a few of the many co-work spaces established in strategic city-centers across the United States. And despite a diversity of types of work being done, the spaces themselves look similar -- open, airy floor plans, in warehouse-y buildings with plenty of trendy-kitschy furniture and wall-art -- suggesting that cooperation and mutual inspiration go hand-in-hand with strong wi-fi and free coffee.

This aesthetic is something that established businesses also try to capitalize on -- to boost business in China, where coffee doesn’t sell so well, Starbucks expanded their stores’ square-footage and cushy furniture to create that “third place” atmosphere. It’s not uncommon for Chinese company-workers to refer to Starbucks as a “public conference room”***, so Starbucks must be doing something right.

The second Market Revolution in workplace design arrived by way of the internet and wireless technologies. The third will no doubt deal in building technology and distribution systems. Consumer tech has transformed so drastically in the last ten years, whereas start-ups still bid for cheap rent in turn-of-the-century warehouses. The future of work will arrive when the systems that take care of us become smaller, portable, transformable, and perhaps even personal.

To keep tabs on where this trend is headed, we'll be posting updates on "Serendipity Machine" workspaces in the comments section. Stay tuned!

Citations:

*“The Market Revolution”, Crash Course U.S. History, #12.

**"You're Not Alone: Most People Hate Open Offices", Ariel Schwartz. Fast Company, November 20, 2013.

***"In China, Starbucks doesn’t sell coffee to make its millions. It rents couches", Gwynn Guilford. Quartz, September 17, 2013.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

4 Comments

on a somewhat related note Bruce Sterling recently wrote "*I bet that new chair works great, too. The Steelcase 'Leap' chair works just fine. Though, if you’re doing all your work with some kinda newfangled Korean 'fonblet' these days, you likely ought jump up and fling your Leap right out the window. Am I right, Steelcase? Heck yeah I am" re: the new SteelCase Gesture the first chair designed to support our interactions with today's technologies.

"Serendipity Machine" spotted: AirBnB's new headquarters (in San Francisco, naturally). Gensler's design embraced the open floor and vaulted ceilings of its formerly industrial quarters, with an added homey twist -- modeling niche workspaces after a few choice residences swapped by the site's users.

Hi Amelia,

this is a great piece, thanks. I think you understand our model extremely well, particularly its perils as well. When I wrote The Serendipity Machine, I was quite enthusiastic about a company really seriously creating a model involving social capital, third space and all the rest of it. However, you are absolutely right, there is a realistic danger of managers turning serendipity machines into new kinds of NSA-Taylorist apparatuses for the sake of increasing social productivity. What I wonder tho is this: wouldn't that just lead to the disappearance of serendipity and thus a short-circuiting of the model?

@ Sebolma -- I completely agree; taken to the most extreme end of social control, modeling for serendipity becomes an oxymoron. By architecting every "serendipitous" encounter, they cease to happen by chance. But so long as the model can be constantly refreshed through democratic uses of space, employees will have a say and the environment will fluctuate accordingly.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.