Navel-gazing has become a data-driven sport. We are awash in technology that allows us to track our own activities, and then take responsibility for that scrutiny, holding us accountable for calories consumed or credit cards exhausted. The quantified-self movement can be a sandstorm of uselessness, or it can sublimate into constructive action. If we try to focus our navel-gaze to better understand ourselves, it seems imminent that such scrutiny will next focus on the brain.

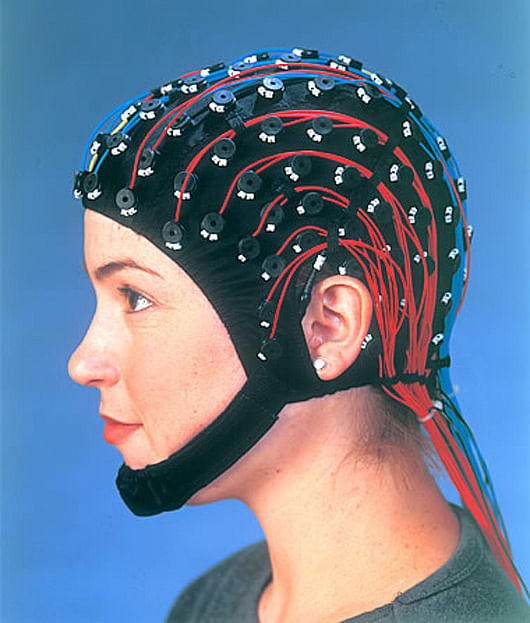

It’s already possible (and relatively cheap) to track the brain’s electrical activity while mobile, using portable EEG headsets. Electroencephalography (EEG) measures electrical activity along the scalp, and can be used in relatively simplistic brain imaging*. With no more physical impediment than Google Glass (social acceptance is not guaranteed), anyone can record the electrical impulses coursing through their brain while they bike to work, cook dinner or walk through the park. To the average consumer, the potential uses may not sound so compelling -- while EEGs illustrate basic electrical activity to diagnose things like sleep disorders, comas, or brain death, they can’t read minds. But these devices could be used to form more robust descriptions of how we relate to our surroundings, by helping us quantify (in broad strokes) our experience navigating spaces.

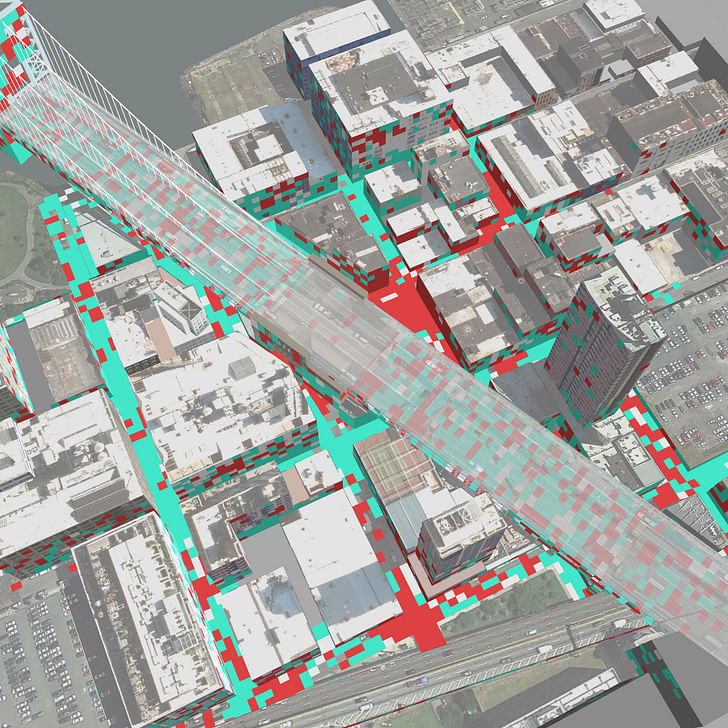

Columbia University has already has carved out initiatives specifically towards this end. The GSAPP Cloud Lab is focused on understanding environmental design through emerging technologies, particularly through computing devices. One of their recent studies mapped participants neural activity as they walked through Brooklyn’s DUMBO neighborhood, each person outfitted with a NeurosSky Mind Wave headset and a custom app to coordinate Beware a new phrenology of architecture, assigning “good design” to something that stimulates an exclusive area of the brain.location and neural activity. The resulting data could be over-layed onto a map of the neighborhood to show where participants experienced meditative or alert states. A previous study at the University of Edinburgh measured similar distinctions between bucolic and urban settings, using the more classic EEG skullcap headset*.

From the experimental perspective, such studies are quick to amaze, but the data is ultimately unscientific. It’s nearly impossible to assign precise correlation, let alone causality, in the completely uncontrolled urban environment. On a city street, it can be nearly impossible to isolate a single stimulus as causing a particular neural impulse, and each participant’s brain could be wired to interpret the same stimuli differently, not to mention the unavoidable self-awareness of “I’m wearing an EEG sensor”. A probable next-step towards scientific rigor is to use digital simulations of urban environments, via Oculus Rift of similar hardwares, in sync with BCI’s to model controlled studies. Get those neck muscles ready for a whole lot of headgear.

But brain computer interfaces (BCI) like the headset used in the DUMBO study can step above other survey methods* of human relationships to environment, by translating intuitive or subconscious understandings into data. Post-occupancy interviews could be coupled with neurological heat-maps. We know that walking through a park is more relaxing than along a urine-soaked sidewalk, but now we can empirically defend it. Or perhaps more importantly, data from BCI’s could be used to challenge popular assumptions, or help form more nuanced understandings of slight contrasts in individual reactions.

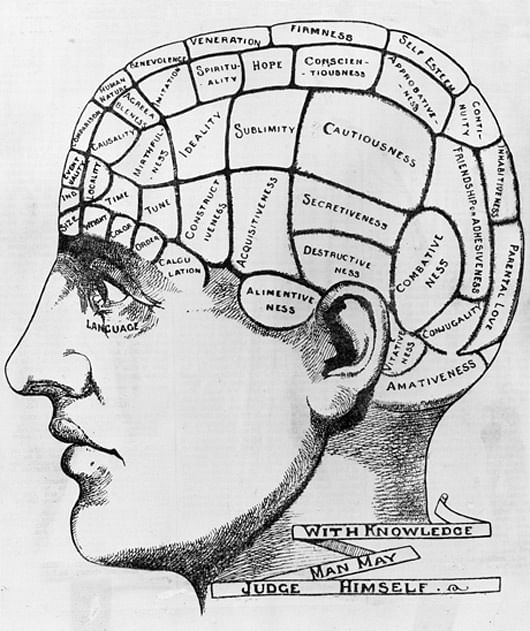

Using BCIs in observations of urban spaces is now quite accessible, but relying on them for precise evaluations of the built environment seems far away. The farthest jump would be to incorporate BCI-modeling into the actual design process, so the built environment is literally designed with your brain in mind (or the collective preferences of the brains of its users). Beware a new phrenology of architecture, assigning “good design” to something that stimulates an exclusive area of the brain.

Architectural borrowings from the natural sciences are certainly not new, but a vocabulary and methodology for neurologically data-minded design doesn’t yet exist (so far as I know). A future architecture, where architects collaborate with cognitive science and neuroscientists at the primary level of design, could provoke a whole new idea of what “human scale” means. Building environments with its users’ neurological biases accounted for could dictate an entire new discipline of architectural research, and empower designers by making informed choices. Environmental psychologists are in some ways tasked with this study, but they aren’t designers -- they are not directly responsible for materializing their conclusions into physical architecture.

Focusing on neurological data is also one method of achieving a more empathetic architecture — that is more complementary, rather than constricting, towards its users’ needs — but it could not possibly dictate every aesthetic decision. The human architect-slash-A future architecture, where architects collaborate with cognitive science and neuroscientists at the primary level of design, could provoke a whole new idea of what “human scale” means.neuroscientist designer would ultimately imbue the project with their style, hopefully inspired by scientific constraints rather than restricted. And neurological studies could never be the entire solution to any design problem, but including that data in architectural research methods can only create richer architecture. It could even provoke a renaissance in local architecture, where connection between designer, user and environment are more tightly woven. Critics of architecture’s globalization see it as a homogenizer, cutting life-lines between designers and citizens, and these research tools are one means of helping reconnect that bond.

Another advantage of an additional trans-disciplinary link in the architectural research chain is that it can create a larger, more diverse readership and demand for what could otherwise seem esoteric. For example, connections have already been established between former soldiers suffering from PTSD, and adolescents living in high-crime urban areas, bridging two ethnographic groups and forming connections between disparate urban spaces. It’s hard to imagine a discipline unrelated to the built environment, that couldn’t benefit from such research.

So if an entire design methodology could be replaced by the “if this, then that” analysis of a neurological read-out, how does this change the designer’s role? Fickle business arises when it becomes obvious, after a few superficial surveys, that what we say we like doesn’t always jive with what our brains show us liking. There are some fantastic evolutionary holdouts here, where certain forms trigger fight-or-flight hormonal impulses in the human brain, at one time necessary to survival -- sharp and angular means dangerous, curvy and soft means safe. The distinction between intellectualized preference and atavistic response suggest that sometimes, humans seem to choose things that they may viscerally dislike. There may be an aesthetic innately preferable to humans, but that doesn’t mean we’ll buy it.

Playing on this distinction, Dutch artist Merel Bekking created a series of household objects based on the preferences measured by MRI scans. The result is a stylized translation from data to object, of course mediated by Bekking’s own aesthetics, but theoretically representing a perfectly logical consensus of the sample group’s design preferences. Ask the people what they want, and give them the candy their brain craves. In this particular instance, participants in the study volunteered preferences for “blue” and “wood”, but according to their scans, they liked “red” and “plastic”.

MRI technology is already used to parse consumer preferences (both physical and intellectual), a practice known as “neuromarketing”. That the resulting forms of Bekking’s experiment are ... not so irresistible belies the futility of a perfect design “consensus”, but it also shows that such technology is limited to the stimulus-response relationship. The preference can only be measured by how they affirm or deny currently existing forms. If what we say we like doesn’t always jive with what our brains show us liking.design and architecture should contain a challenging element, one that momentarily rattles the viewer in a compelling way, then there may be an incentive to ignoring the neuro-suprematist angle.

It’s easy to rely on data as a seemingly objectivist design method, but it’s only a drop in the bucket towards creating sustainable, relatable and compelling architecture that is a joy to experience. Gathering nuanced neurological data related to our interactions with the built environment won’t be the silver bullet for an all-pleasing urban environment, nor should that be the goal. BCI’s and more advanced brain-imaging technology will allow us to better understand the built environment’s effect on mental health, contributing to creating healthier spaces and healthier citizens. It’s a tool for public health as much as urban design*. We are creatures of our environment, whether we admit it or not.

AfterShock is a non-conclusive series that grapples with the impact and responsibility of contemporary architectural design, hoping to instigate dialogues on how to make architecture more accountable.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

8 Comments

http://cargocollective.com/ryangriffin/Sensory-Deprivation-S-t-imulation-Treatment-Center

This is a great article - it's exciting to see that this kind of thing is being investigated. (for better or for worse) Above is a link to a project I did in school a couple years ago with a strong focus on this subject.

@ Ryan, thanks for sharing your project. Therapy and punitive spaces make explicit the psychological effects a certain built environment is supposed to evoke, so in a way they could be helpful as a "control group" in neuroscientific experiments.

great feature article. just started charging the old EEG headset and will return to my "modeling 3d" by thought project this weekend...

with regard to " a vocabulary and methodology for neurologically data-minded design" I think a few videos from http://www.anfarch.org/videos/ might address this.

I'm specifically thinking of the lecture by Eugenia Ellis of BAU Architecture with regard to lighting and the circadian rhythm

I think this is the link - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SQnqmFaHmE0&list=PLJrgKNDl6Lry0nd8AsqELhHUs4-vGfb5q&index=32

@Chris, thanks for those links! I just recently became familiar with ANFA and plan on attending their 2014 conference in September.

Speakers include Juhani Pallasmaa, who does a lot of thinking/writing on how we describe psychological experience in space, and evaluate it. We featured his piece "Orchestrating Architecture; Atmosphere in Frank Lloyd Wright's Buildings" in our Screen/Print issue for OASE Journal.

Thanks Amelia - It appears I have some reading to do and hope you'll be reporting on ANFA this September, wish I could attend.

In philosophy "psychological experience of space" can fall under Phenomenology. There is a sub category of Neurophenomenolgy Discovered it via Evan Thompson who with Francisco Varela and Elanor Rosch wrote the "The Embodied Mind" . At one point I reached out to Evan Thompson by email while he was at U. of Toronto and he directed me to what now appears to be Neuro Logics.

The upshot, I see a very good link between trained architects and neuroscientist to avoid what you cover above as 'decision by data'. The Embodied Mind explains in a few parts, similar to Buddhism on many fronts, that to properly understand the brain readings by EEG's, etc.... the person being read should also be trained (philosophically) to be able to make distinctions in phases of the mind thus correlating conscious moments with data. This obviously proves a bit of a challenge for legitimacy within western science standard mode of operations with regard to "objectivity" while ignoring the "subject" perceiving the objects.

I think as a good option for finding a 'legitimacy' to the art and science of architecture, neuroscience, and more specifically phenomenology-neuroscience-architecture is a very exciting path what tons of potential.

This is a great article. It reveals a lot about the current state of architecture that such ideas that where commonly understood need this kind of scientific study to be brought back into the discussion of what architecture is. Be that as it may, this is where we are and I love that our human nature is finally being brought (back) into the discussion. Another method of studying how we respond to our environment is to ask people not trained in the architecture profession. We tend to over analyze things or be suspicious of elemental feelings so we don't always understand intuition as well as we might think.

"From the experimental perspective, such studies are quick to amaze, but the data is ultimately unscientific. It’s nearly impossible to assign precise correlation, let alone causality, in the completely uncontrolled urban environment"

Of course not with any scientific certainty, but that's not how artists usually work. Impressions can be as useful and possibly more truthful than data, which is our current sacred cow. Then again, the anotomical studies (data) that Michelangelo did was invaluable to developing his natural compositional skills.

"Focusing on neurological data is also one method of achieving a more empathetic architecture — that is more complementary, rather than constricting, towards its users’ needs — but it could not possibly dictate every aesthetic decision."

As a 'human architect-slash-neuroscientist designer', I've found the best way to empathize with our fellow human is to ask how they feel, regardless of one's biases about their class or educational level. It's especially hard for progressives (of which I'm one) because they couldn't imagine themselves being close-minded. Oh, well, I guess we're like everybody else, which means their aesthetic choices might have something in common with ours. Why do they go to Venice? What's attractive about a tree lined street-car suburban main-street? What's with all the facial hair, rectangular glasses, and black tee-shirts? We all use aesthetics for similar reasons. To communicate something about ourselves to others. To express our status, our politics, our personal space. Humans have been doing this and more with their buildings as long as the first human settlements went vertical.

I'm not saying we should study or learn from tacky strip mall architecture (sorry Venturi) but clearly we have a need that our current architectural system isn't addressing, or these scientifically blessed studies wouldn't be so appealing today. It's a wonderful thing that this change is happening, but let's not let the data take over so completely that we leave no room for human intuition. If you want to wear a skirt, man or woman, I say go for it, and if you want to slather some Roman wreaths on your bay window, why not. San Francisco, what a beautiful (and progressive) city!

""Gathering nuanced neurological data related to our interactions with the built environment won’t be the silver bullet for an all-pleasing urban environment, nor should that be the goal....We are creatures of our environment, whether we admit it or not."

I admit it! Looking forward to the next installment, conclusive or not.

Fantastic.

Awesome

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.