You’ve heard it before. In the span of architecture folklore, this origin story is old hat: I wanted to become an architect because it combines art and science. As pithy as it sounds, this always struck me as problematic, because it presumes that such a combination is easily wrought. What is really going on, at the arguably-genetic root of architectural practice, that manages the push and pull between expression and empiricism? Architecture occupies that limbo space between the quantifiable and the phenomenological, and that gap is insistently being narrowed by technology – not only in design, but in how we actually perceive our surroundings.

The Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, aka ANFA, is one such organization trying to bridge that same gap. Started as an AIA San Diego offshoot in 2003, ANFA is now a non-profit resource for architects looking to incorporate neuroscientific observations into their design. At first glance, the utility of neuroscience for architects may seem like a spoon when all they need is a knife, but the movement has gathered steam, in parts due to technological innovations, and federal support. In a 2005 paper entitled “Translating Neuroscience into Design”, Eve Edelstein (who holds a PhD in neuroscience and serves as an associate professor of architecture) introduces the term “neuro-architecture”, referring to “a instead of scrutinizing materials or building physics, we’re scrutinizing ourselvesnew discipline that unites the emerging field of Neuroscience with the experience of architecture.” Her paper goes on to propose “a model of ‘translational design’ ... that utilizes information from the basic and clinical sciences as well as the rigorous methods from science to enhance and inform the design of built settings.” In 2011, in a paper published with Eduardo Macagno, professor of cell and developmental biology at UCSD and an organizer of ANFA’s 2014 conference, Edelstien develops the “translational neuro-architecture design” hypothesis further: "In the domain of architecture, a scientifically derived "neuro-architectural" hypothesis may be used to articulate a testable idea about how a specific feature of design may influence psychological or psychological processes that may in turn be associated with measurable changes that reveal the impact of the built environment on human health."

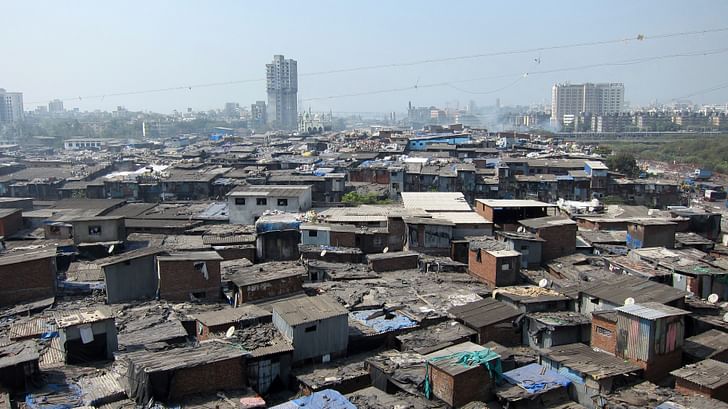

Neuro-architecture is steps beyond other scientific adaptations to architectural design, because instead of scrutinizing materials or building physics, we’re scrutinizing ourselves – the humans interacting with the built environment. Previously, phenomenological interpretations of architecture were scientifically irrelevant – verbally describing how you experience a space doesn’t translate into quantifiable defenses. But recognizing the values and trends inherent to “evidence-based design”, which tends to be based on focus groups and qualitative interviews, ANFA is of the more hardcore persuasion that urban environments are becoming humanity's natural habitatneuroscience can paint the nittiest, grittiest picture of the human reaction to space, and should ultimately be used to help guide best practices in architecture. Their initiatives come at a good time. President Obama’s BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies), announced last April, has pushed $100 million to organizations like the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), to "do for neuroscience what the Human Genome Project did for genomics". So neuroscience in the US is getting more of a taste of the limelight, and architecture stands to gain some residuals. And as 54% of the global population lives in cities, with growth rates projected to continue into the next thirty years, urban environments are becoming humanity’s natural habitat. Understanding the psychological effect of this is vital, and it’s inevitable for that to trickle down into architectural design.

I have no doubt that neuroscientific research stands to expose fascinating connections between mental and aesthetic experiences, but I was still hesitant to buy into phase two: how architects can actually command this neuroscientific analysis in their designs. So I went down to San Diego to attend ANFA’s three-day conference at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies with my Kool-Aid cup in hand, but not quite ready to drink up. I was curious to see, amidst research papers, design methodologies and new technology demonstrations, how both parties’ esotericisms could somehow combine into an intelligible new form of architectural practice. In short, how to make better architecture by better understanding what it’s doing to our brains.

It’s a concern that is practically written all over the walls of the Salk Institute, the insistently photogenic research laboratory designed by Louis Kahn, in collaboration with Jonas Salk, founder of the polio vaccine and ideator of the Institute. It’s undeniable that The Salk has a great effect on people, whether architectural pilgrim or scientist or neither (as a public place, it has an average 5-star rating on Yelp). And it’s not really surprising, given the building’s impressive number of cosmological elements: the mirroring rows of tall, rectangular lab facilities, separated by a courtyard, reflect perfectly Vitruvian bilateral symmetry, with an axis of water running (barely audible) down the center. The water flows towards the Pacific Ocean, perfectly perpendicular, such that during an equinox, the sun rises and sets along the same path. Kahn designed the row of towers with a solid-void ratio according to patterns of the Fibonacci sequence, and the teak wood paneling visibly ages at a geological rate determined by coastal and desert factors. It’s hard to avoid the existential elements in this building, even without all that trivia – just standing at the main entrance, your view of the Pacific is surrounded by a periphery of light reflected off the travertine and concrete, funneling your gaze through the rows of buildings onto the ocean’s horizon, and into the great beyond.

Salk wanted his Institute to accomplish something similar to what he had experienced at the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi, before finding the cure for polio in 1955. Stuck in a rut in his research, frustrated, Salk hoped that a change of scenery would help, and the atmosphere of the Basilica did the trick – he returned with the insights he needed, refreshed. Now, researchers in neuroscience at his very institute are trying to hone in on precisely what the built environment can do to our psyches, using data culled from fMRIs, EEGs and countless other technologies to read the writing on the wall.

But deciphering neurological activity into relatable adjectives like “comfortable”, “anxious”, “curious”, or “relaxed” is difficult and imprecise, let alone knowing exactly what design element is causing what response. While some technologies, such as EEG, allow us to study the human brain non-invasively, while they’re active in a space, the data isn’t anywhere near as precise as it needs to be. Getting that level of data (with today’s technology) means literally invading the brain while the subject is active, something that isn't allowed in laboratory testing of most human subjects.

Until then, we’re stuck with mostly rat-to-human analogies. But that doesn’t mean the research doesn’t have profound human implications, or explicit extensions. In her ANFA presentation on what is now a Nobel-Prize winning research topic, neurobiologist Jill Leutgeb explained how a rat’s neural activity changes as it navigates a new space. The Grid cells are a chessboard, and place cells the chess pieces.hippocampus is an evolutionarily ancient region in the mammalian brain that plays an integral role in memory formation and way-finding, and contains both “place cells” and “grid cells”. Place cells are specific neurons that become active in relation to a specific space, forming a spatial “memory”. Grid cells create a coordinate system to aggregate and organize, or “map”, those spatial memories formed by the place cells. Grid cells are a chessboard, and place cells the chess pieces. And evidence of both these cells have shown up in humans, using enhanced brain imaging technology and neurological surgeries, cited by the Nobel-winning neuroscientists. The research holds great promise for Alzheimer treatment as well, where spatial loss is often one of the first casualties.

The technical advancements in neuroscientific research have developed rapidly within the last thirty years, creating access to a remarkably nuanced vision of what’s happening inside our brains. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technology, developed in the early 1980s, was the first to capture individual neuron activity in living humans, non-invasively. Much of what was intuitively known about brain behavior, we now can cite supporting neuro-biological evidence culled from fMRIs. And as it turns out, most people are more likely to be compelled by a robust spreadsheet of data (that can hold financial water) than anecdotal phenomenologies. Architects know this, and it infuriates them. One speaker at the conference who asked not to be named, frustrated by clients hassling him over design decisions that he believed self-evident, wished for concrete neuroscience data for concrete design elements. That way, he could compel clients to trust his design expertise by appealing to their desire for “hard, scientific facts”, rather than, say, the architect’s immense industry training. In his view, his expertise as a designer was insufficient to establish that baseline trust that exists between client and architect, but enough data would flip the switch. But why should referencing analogous studies with rats be more compelling than a design professional’s opinion?

At its essence, ANFA is all about creating an empirical phenomenology. It’s easy, especially as a non-scientist, to get excited about the attempts to quantify our experience in space through neuroscientific data – and then try to wield that data to create better architecture. But there’s some real hiccups in that process that can’t afford to be overlooked. Eduardo Macagno, in his elegant ANFA presentation entitled simply “Overview of Problem”, made quite clear the limitations of trying to apply scientific methodologies to architecture. Proliferations of commercial-level brain-imaging technologies and brain-computer interfaces, as well as remarkable approximations of space in virtual environments, does not mean we’ve successfully turned architecture into a scientific subject. A few papers presented at the conference (like Pati and O’Boyle’s “An fMRI-Based Exploration of Neural Correlates of the why should referencing analogous studies with rats be more compelling than a design professional’s opinion?'Forma' Environmental Attributes of Healthcare Settings", for instance) cited studies where participants were asked to respond to an image of a piece of architecture – just that, a two-dimensional image, no more immersive or experiential than flipping through an Instagram gallery. But at this time, it’s a necessary bargain, because the real world is too thorny of an environment to ever be cast as a controlled setting for scientific research. Social scientific research, sure, of course, but neuroscientific? The next best thing for the research now, then, is to resort to virtual realities.

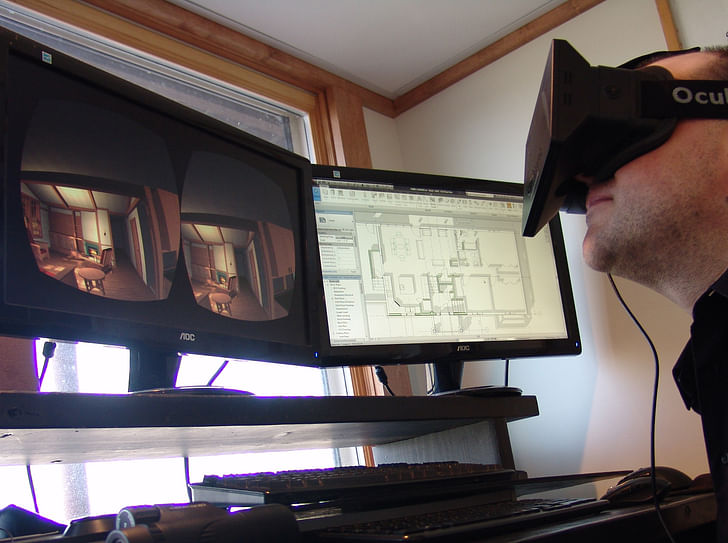

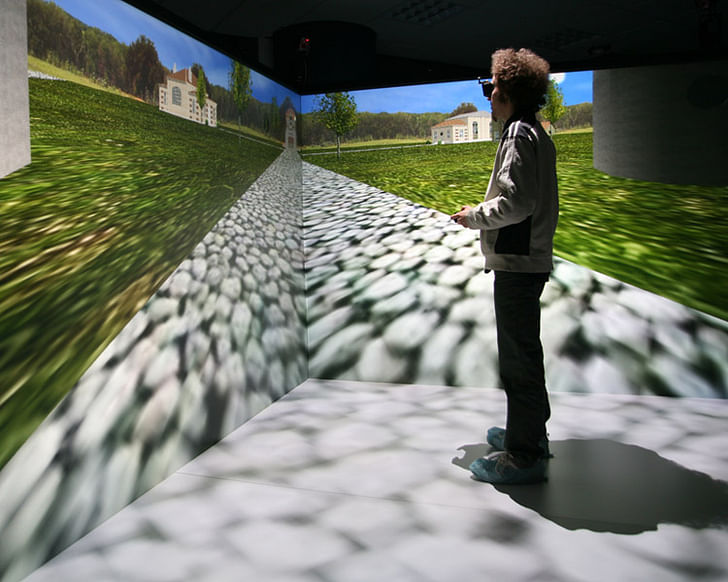

Currently, two virtual reality applications dominate architectural research: CAVEs (Cave Automatic Virtual Environments) and head-mounted displays (such as the Oculus Rift). As the name suggests, CAVEs are essentially rooms whose walls display a virtual 3D environment, depending on the perspective of the subject inside. Head-mounted displays tend to feel more immersive, because they completely overwhelm the subject’s vision (sometimes to the point of nausea), and can be adaptive to body, head, and even eye movements. Hannah Hobbs, presenting her M.Arch thesis project, aspired to create semi-immersive virtual environments to study how people responded to different curvatures in otherwise comparable architectures. The goal, strongly embedded in evidence-based design’s agenda, was to identify which types of curvatures were most therapeutic for hospital patients. Hobbs coined the term “CAVEtte” to describe the semi-immersive CAVE system she developed for her research with architect Kevin Sullivan, in part to cross-examine her findings when the stimuli was images of the same surroundings.

The next best thing for the research now, then, is to resort to virtual realities.CAVEs won’t be the silver bullet to architecture’s science problem, but they’re a good analogy to inform research. Much esteemed for his work linking artificial intelligence and the human brain, Michael Arbib, a professor of Neuroscience and Computer Science at USC and member of ANFA’s Board of Directors, defined “neuromorphic architecture” as “what happens if architecture incorporates in itself some of the lessons of the brain. If, in a sense, you give a brain to a building.” This can then be used to establish a defensible foundation of architecture analytics that isn’t wholly about sight or feeling. In an address to ANFA’s crowd in celebration of Salk’s 100th birthday, Sarah Goldhagen, architecture critic for The New Republic and established scholar on Louis Kahn, explained the role Kahn’s works had played in her own professional development. She recalled how, in the 1990s, her emotional interpretation of Kahn had placed her in the “deeply uncool” phenomenological hinterlands of architectural historical thought, when the predominating postmodern theory prioritized anything but feelings. Moving with the academic tide meant away from phenomenological readings, but now, returning to the Salk with updated neuro-imaging technologies and insights, that phenomenological interpretation can stand trial.

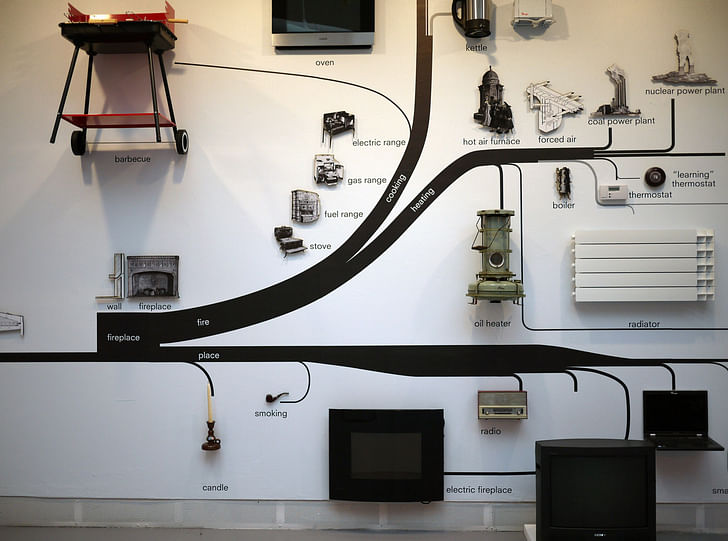

Of course, there have been attempts to formalize architectural interpretation before, most notably and recently, at this year’s Venice Biennale of Architecture. The "Elements of Architecture" core exhibition, curated by Rem Koolhaas, broke architecture down to fifteen physical forms (toilet, door, window, floor, ceiling, etc.) that purportedly informed all of architecture history. The curation hinted at a “how did we get here?” consideration of contemporary architecture practice, while also effectively defining the terms of architectural discourse. Taking an aesthetic object and trying to break it into discrete, inalienable parts is effectively a control mechanism, creating a formal language by which things are described and categorized – a practice absolutely essential for any serious discipline. What Koolhaas did for architecture’s physical form at the Venice Biennale, ANFA is doing for its experiential form.

A huge element in all this research, and its utility for architecture, is trust – whether architects are invested enough in this new data to be convinced that it’s actually a beneficial design tool. Effectively, whether or not architects can use this data to better compel clients. “If architecture leadership is looking for a purpose, where what we can do can be understood, can be codified, can have increased perceptive value, this is it,” explained Betsey Dougherty, partner at Dougherty + Dougherty and board member of ANFA. And evidently, schools are beginning to think so too: programs combining architecture and neuroscience already exist at the New School for Architecture in San Diego and Texas A&M University, and ANFA’s conference included speakers from architecture schools worldwide, at the University of Waterloo, The Bartlett, Cornell University, University of Sheffield, UCLA and USC.

By the final day of the conference, I drank the Kool-Aid. Considering neuroscientific research as the next-level of evidence-based design methodology, we stand to better understand how we live, work and play in the built environment. And in the longer term, show how our urban habitats change not only our brains, but ourselves.

AfterShock is a non-conclusive series that grapples with the impact and responsibility of contemporary architectural design, hoping to instigate dialogues on how to make architecture more accountable.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

6 Comments

It's amazing to see architectural media and academia embracing this stuff. Evolutionary biologists have long understood what centuries of architectural theorists have intuitively known, but for those who continue to mistrust empiricism, finally there's a scientific basis for why people prefer certain environments over others. Architecture is the art of building, plain and simple, with out ideological constraints or theoretical boundarys. Not to say that one can't or shouldn't be informed by an overarching philosophy, but one needs to acknowledge that those levels of interpretation are usually closed off to the end user. Ironically, those who rely on thier intuition rather following a scientificly based formula will always produce more meaningful work for the simple fact that we are ourselves an instinctual core with an analytical overlay. When and how these findings will fully percolate into the curriculum has yet to be seen, but the neurological understanding of how we 'inhabit' our built environment is now a matter of science, and not just nostalgic patter.

Then again, if one simply observed children at play...

I have a hard time seeing how this provides more meaningful feedback than occupant surveys. If my neural response indicates comfort but I say I don't like it, what should we conclude?

That said it's worth further study in order to better develop knowledge of the brain's spatial processing systems. I can't wait until I can wear some headset that makes revit models of whatever I'm thinking!

"I have a hard time seeing how this provides more meaningful feedback than occupant surveys"

Great point. It dosen't, but there is a built in skepticism of the kind of surveys you are talking about, ie, those involving non-architects. A year or so ago they had this post about "Why architects don't give people what they want", something that you would think occupent surveys might inform you on. 1600+ comments latter and some where still arguning that average people don't know their heads from their asses. It's only after the Salk Institute folks diagram it out that the 'illuminati' deign to listen. Again it's lovely that this is finaly coming to light, but how could Joni Mitchell and Chrissie Hynde be wrong?

Amelia - great piece and like how you link all your news posts into a feature story.

When I lose inspiration in the science and art of architecture, mainly due to the legal and financial aspects of architecture, I look at Frederik de Wilde's work, specifically Nano Painting (blackest black nano engineered artwork (painting), collaborators - Rice University, NASA , Michigan University)

So this whole Neuroscientists and architects working together is great and progressive. Although, much of what is going on now is data gathering, it is considerably more useful than just survey stats.

But as midlander suggests, humans are a weird breed, capable of conscious denial of their very own emotions and phenomenological experiences of architecture or anything for that matter. Maybe architects are in denial of what's good for humans? (we've known this for decades)

Thank you for the government sponsored brain link programs, nearly forgot. Have a project I am doing with a very smart kid majoring in BioEngineering & NeuroScience (i think), it's not exactly an architecture project, but its definitely art, computer science, and phenomenology. I couldn't justify the project any other way, than using science to make art. Hopefully full scope done by end of year.

"I can't wait until I can wear some headset that makes revit models of whatever I'm thinking!" and yes midlander, I'm working on that too...data collection is boring, modeling with the mind would be much more fun, no?

Chris, your quote "I couldn't justify the project any other way, than using science to make art. Hopefully full scope done by end of year", encouraged me, to call out the one obvious upside to the term "translational".

Esp., coming from an academic/healthcare industry background, where the term has become all the rage in the fight for funding. With higher education's trend toward STEM and research dollars, neuro-architecture could at worst provide a way for depts to increase their ranking/presence on campus.

While also meeting a parallel NSF trend for academic R&D research collaboration.

"neuro-architecture could at worst provide a way for depts to increase their ranking/presence on campus." , agree Nam and I think Amelia may have been really hinting strongly at this fact in the last pod-cast. Architecture could enter the world of Nobel prizes, right?

thanks for the link and if you have any good examples of the term "translational" in use for funding apps let me know, may try to fund this through a non-profit after this phase in the project (each phase being it's own project)

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.