Screen/Print is an experimentation in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we’re featuring The Petropolis of Tomorrow.

Do you run an architectural publication? Are you particularly excited about an upcoming periodical? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Over a hundred miles off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, a new frontier urbanism is evolving. Floating company towns, termed petropolises, have been built to support the people and resources devoted to extracting offshore petroleum. Originally initiated by Neeraj Bhatia and Mary Casper as a design and research project at Rice University, The Petropolis of Tomorrow investigates how urban form grows from resource extraction, and how these petroleum “company towns” could offer new models for sustainable urbanism.

While accepting that petroleum is imminently unsustainable, petropolis urbanism seeks to respond to immediate needs while modeling sustainable alternatives -- a realpolitik approach to a frontier architectural type. In the following excerpt from the foreword, Neeraj Bhatia explains the current state of Brazil’s petropolises, and how they represent an environment akin to historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s American frontier: “the outer edge of the wave -- the meeting point between savagery and civilization”.

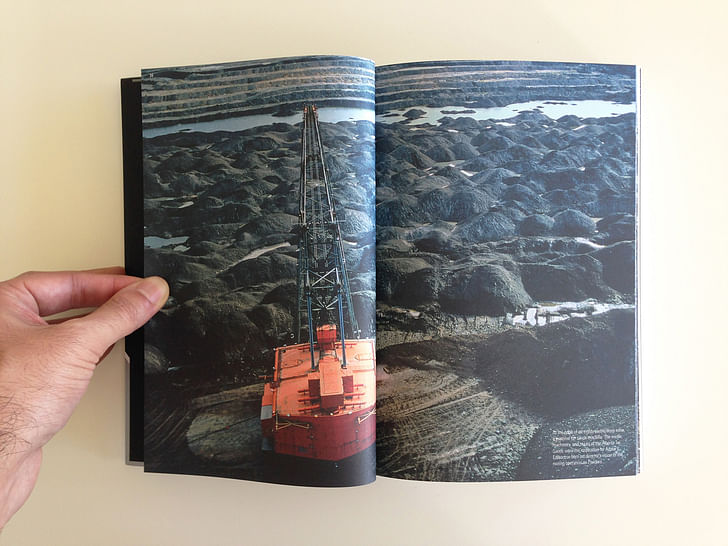

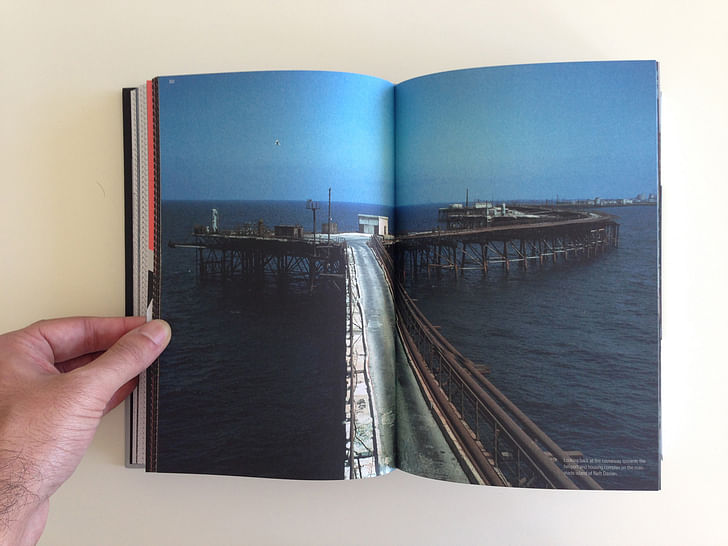

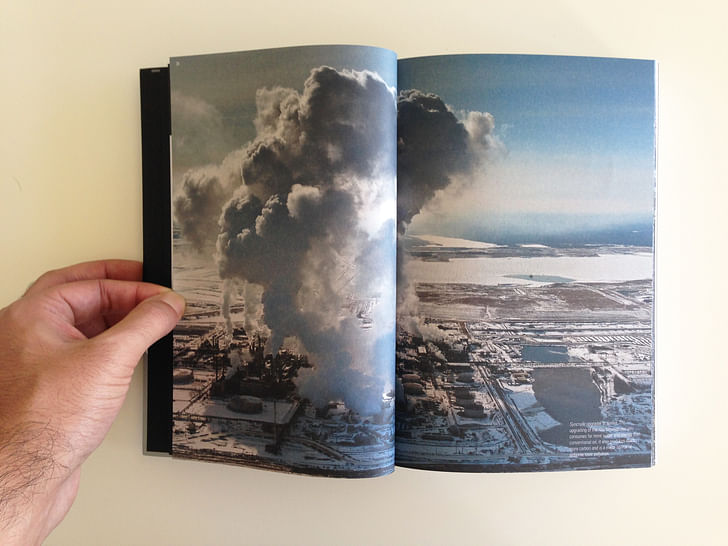

Brazil, a nation that relies on ethanol for forty percent of its fuel supply, has in recent years also become one of the largest oil producers in the world. The latest oil discoveries in the Campos and Santos Basin, off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, are destined to put Brazil in the coveted top ten of oil producing nations globally. The Tupi and Jupiter oil fields (discovered in 2007 and 2008) have recently been surpassed by the Libra oil field, which is estimated to hold as much as fifteen billion barrels of oil. Approximately 114 miles off the coast of Rio, Libra and newer discoveries are tending to be located further into the sea. However, not only is this oil becoming difficult to access from the coast, it is also deep below the water’s surface, underneath the pre-salt fields. Despite these obstacles, in September of 2010, the Brazilian oil company Petrobras raised over seventy billion dollars in the world’s largest public share offering to extract this petroleum, unleashing a new frontier comprised of Petropolises, or cities formed around the logistics of resource extraction.[1]

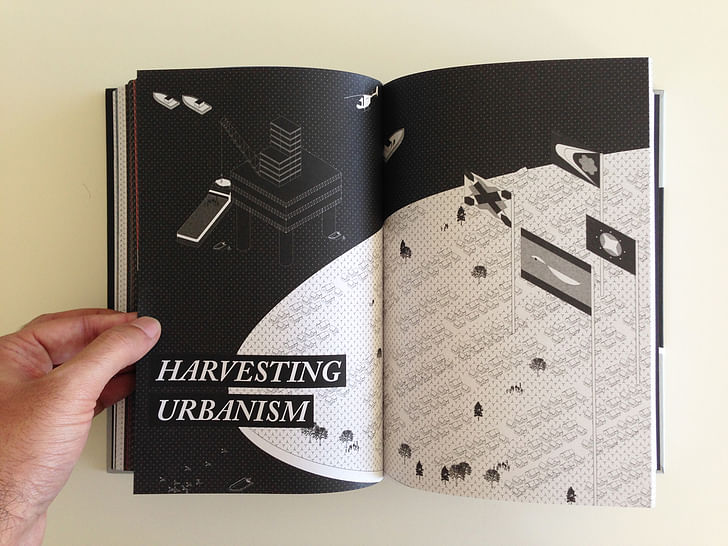

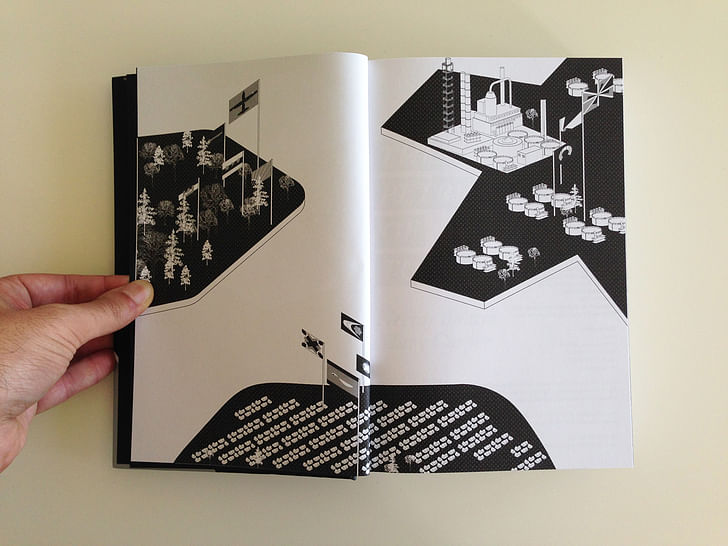

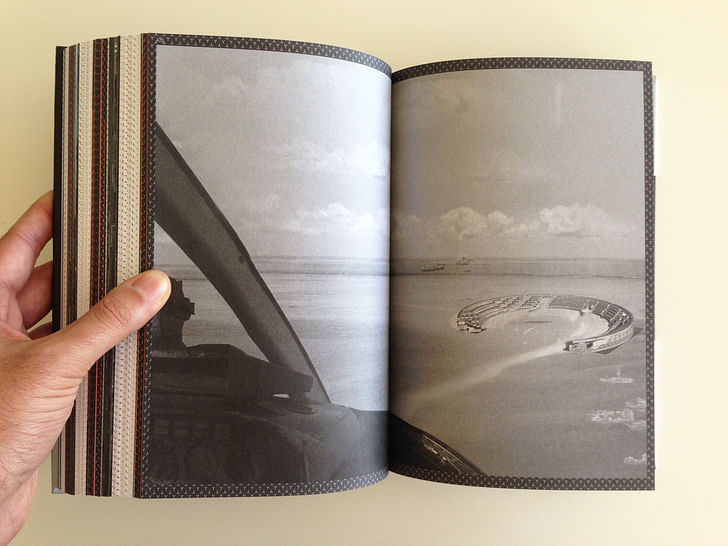

The newest findings in the distant Santos Basin are challenging the traditional notions of the land-based urbanism associated with oil production. Existing beyond the feasible range of helicopter transport, these offshore fields have presented a logistical crisis in the development of several offshore settlements. These ‘floating frontier towns’ are hundreds of kilometers offshore, floating approximately a mile above the sea floor.[2] New artificial island hubs are now being investigated to bridge these distances and to allow for efficient movement of people, as well as storage of materials.[3] The consolidation of distributed populations into a series of nodes, effectively forming a larger core population, is of particular interest in this paradigm shift in the logistics of the offshore extraction industry. As such, these proposed hub islands may include a more diverse, and larger quantity of locally controlled programs that sit outside the global logistics of petroleum. Accordingly, the networks and nodes associated with impending Petropolises have the potential to critically project new forms of water-based urbanism. Currently, eighty-six fixed and forty-six floating rigs serve as workplace for over forty-five thousand people in Brazilian waters[4]. While these rapid developments are forming a new frontier of exploration and urbanism in the Atlantic Ocean, this frontier is largely composed of autonomous fragments that are often overlooked by designers in a holistic manner.

These ‘floating frontier towns’ are hundreds of kilometers offshore, floating approximately a mile above the sea floor. As the number of floating developments increase in the upcoming years, it is worthwhile to speculate on the impact that this frontier will have on Brazil, beyond economic prosperity. In Frederick Jackson Turner’s seminal work, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, he defines the frontier as “the outer edge of the wave—the meeting point between savagery and civilization.”[5] From the viewpoint of a historian and economist, Turner’s Frontier Thesis proposes that the frontier provided a particular set of qualities that were the instigators to American democracy. While it may be difficult to prove that democracy was the result of these characteristics, it is useful to examine the particular attributes Turner ascribed the line of the frontier. For Turner, the frontier was free from British cultural and institutional dogmas that influenced the Eastern United States, therefore providing a sense of independence. Those pushing westward had free land at their disposal and developed skills to control and profit from the ”wild” natural environment, promoting physical strength, economic self-sufficiency, and social individualism. The frontier embodied the tension between ”civilized” settlements and the “wilderness” beyond, and was precisely the wild that Turner viewed as beneficial, as he states, “For a moment, at the frontier, the bonds of custom are broken and unrestraint is triumphant. There is not tabula rasa. The stubborn American environment is there with its imperious summons to accept its conditions; the inherited ways of doing things are also there; and yet, in spite of environment, and in spite of custom, each frontier did indeed furnish a new field of opportunity.”[6] The frontier became such a force of individual enterprise as it expanded, that the legislation of the National Government became conditioned on the frontier itself.[7] A distinct and complex coupling was transpiring on the frontier as individuals here needed to reconcile the local context — both environmental and cultural — with collective national policy and economic trade.

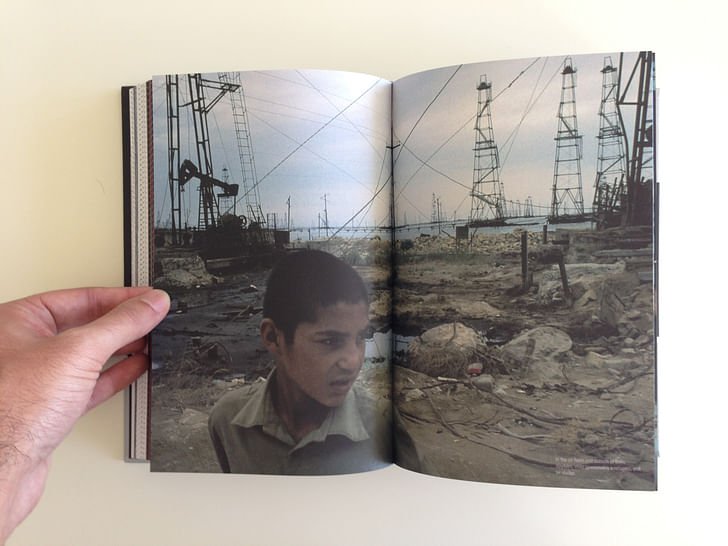

In the context of Brazil, the outward push into the Atlantic embodies several characteristics outlined by Turner at the American frontier. As Rania Ghosn points out in her article, "The Expansion of the Extractive Territory", the pre-salt fields have already prompted legislative changes in Brazil to form a complex geopolitical frontier comprised of several companies and countries. Further, the ”wilderness” — in this case, the turbulent ocean, the great depth of sea bed and salt fields, and the marine ecosystems — showcases the tension between technological control and natural geology. But in the context of the floating frontier, it is difficult to foresee the deep cultural and individualistic impact that Turner witnessed in the American context. Because geologic complexity hinders individuals from staking claims and searching for resources in the Atlantic, the floating frontier is controlled by large corporations and promoted by countries that have the necessary financial backing, technological expertise, and political authority to extract petroleum. These large infrastructures of extraction and logistics continue the legacy of top-down, infrastructural urbanism existing in Brazil, as outlined by Fares el-Dahdah and Alida Metcalfe in the following text. This frontier urbanism, highly contingent on large capital costs associated with infrastructural deployment, operates like an incorporated city or a network of company towns, a term that has been dormant in the past several decades.

The apparent tabula rasa of the sea is in fact a complex and malleable medium comprised of several overlapping visible and invisible systems. Company towns engage frontiers of their own, as they are typically located in remote areas, adjacent to industries, factories, and raw resources. Set within such hinterlands, companies were obliged to provide amenities to attract skilled labor. The criticism launched at the American company towns of the 19th and early 20th centuries has often focused on their paternalistic habits of limiting growth and independence, often requiring unwavering subservience, loyalty, and appreciation to the company, which is in direct contrast to the Frontier Thesis put forth by Turner.[8] So what does the model of a company town afford this research that the individualistic frontier cannot? The last wave of company towns deployed in America are worthy of discussion in this context. During the 1920s, in an effort to appease labor problems while simultaneously attracting skilled workers and avoiding unionization, clients heavily favored the professional expertise of designers. Specialized knowledge within the disciplines of architecture, landscape architecture and city planning, became instrumental in translating new concepts of industrial relations and social welfare into new physical forms.[9] For design professionals, company towns offered an ideal challenge to both clearly define the territory of the discreet design disciplines, as well as to test new forms of urban organizations free of consensus-based design decisions. This allowed architects, while working for industrialists, to implement a holistic urban vision — a rare opportunity in contemporary urbanism.[10]

At least fifty new island platforms will need to be constructed in the upcoming years, making this the opportune moment to question and project a new system of sustainable water-based urbanism. While the promise of the company town lies in its ability to be comprehensively planned, there are obvious dangers that may emanate from a singular design vision. One of the most famous company towns in South America was Fordlandia, conceived of by Henry Ford to produce rubber on the Tapajos River in the Amazon. Fordlandia was “deployed” to conquer and control nature, as stated by the German Daily, “If the machine, the tractor, can open a breach in the great green wall of the Amazon jungle, if Ford plants millions of rubber trees where there used to be nothing but jungle solitude, then the romantic history of rubber will have a new chapter. A new and titanic fight between nature and modern man is beginning.”[11] Ford established an entire city for the ten thousand residents, complete with a “widespread sanitary campaign against the dangers of the jungle.”[12] With deliberate neglect of local cultural practices, Ford instituted American work schedules, food, and Cape Cod style houses to ”modernize” the local workers’ lifestyles. Further, without employing any botanists or horticulturalists, Ford relied on the company’s engineers and the rubber trees never flourished as planned. Fordlandia eventually closed in 1945 at a loss, and became an emblematic warning of the potential failure of any company town so planned and implemented under a single corporate urban vision.

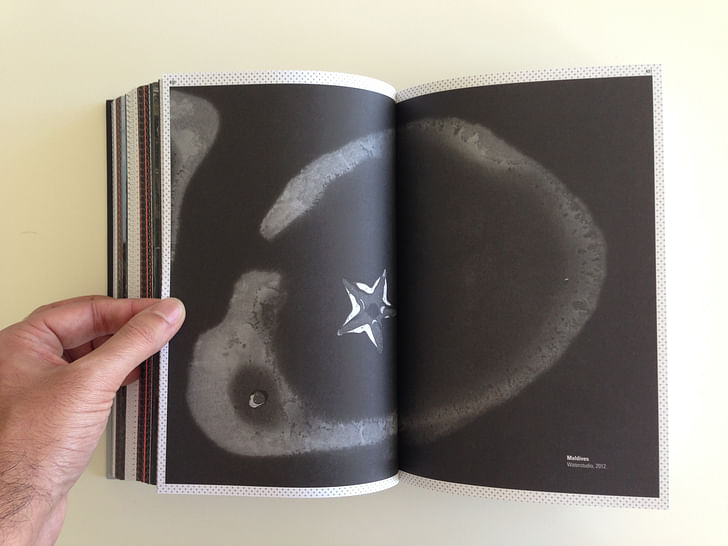

The establishment of artificial islands in Brazil presents a unique circumstance, however, wherein the frontier is developing as a series of privatized company towns. The potential in these future developments lies in their ability to be holistically planned and deployed, crucially taking cues from the surrounding environment and local cultural practices of the “wild” to negotiate the local and global; the individual and collective; and the natural and artificial. Here, the experimentalism embodied in the individualist's frontier, populated by a diverse, dynamic community and sustained through an economy of oil infrastructure, pushes up against the determinism of the company town. Unlike the series of floating cities proposed by the Japanese Metabolists, who recreated the world from within, the water-based urbanism outlined here acknowledges that the apparent tabula rasa of the sea is in fact a complex and malleable medium comprised of several overlapping visible and invisible systems.

Just as Hugh Ferris’s The Metropolis of Tomorrow catalogued an existing reality and its architectural and urban ramifications, working within its logic to project innovative urban organizations, The Petropolis of Tomorrow observes and responds, without succumbing, to the economic and technical realities of the oil industry in order to rethink the social and ecological future of this frontier.[13]

Petrobras currently estimates that at least fifty new island platforms will need to be constructed in the upcoming years, making this the opportune moment to question and project a new system of sustainable water-based urbanism.4 Only through observing, positioning, and projecting visions for this emerging frontier can renewed discussions on resource extraction infrastructure and water-based urbanism move away from individualistic, fragmented viewpoints and rather, respond to Ferris’s call: to direct these components through a holistic vision that includes economics, politics, ecologies, and public realms, through the careful design of the architecture and infrastructure that organize these systems.

[1] Associated Press “Petrobras raises $70bn in world’s largest share offer”, The Guardian (September 24, 2010), http://www.guard- ian.co.uk/business/2010/sep/24/petrobras-70bn-worlds-largest-share-offer

[2] Often termed Floating Production Storage & Offloading vessels, or FPSOs, these floating cities utilize new technology that is being developed in research centers such as CENPES, allowing the separation of water, gas, and water at the seabed to automate the extraction process.

[3] Helen Trouten, “Petrobras Plans Fifty New Floating Cities”, The Rio Times (May 31, 2011), http://riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/ rio-business/petrobras-plans-fifty-new-floating-cities/#

[4] Ibid

[5] Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1921), 3.

[6] Ibid, 38.

[7] Ibid, 24.

[8] Richard Sennett, Authority (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), 57-59.

[9] Margaret Crawford, Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The Design of American Company Towns, (New York: Verso, 1995), 45.

[10] Ibid, 64. NOTE: The success of these towns has been documented. The Urbanism Committee, set up by the National Resource Planning Board during the New Deal, conducted an exhaustive survey of 144 planned towns, garden suburbs, and company towns. The largest percentage (53.3 percent) of the towns the committee examined was industrial company towns. Using questionnaires, interviews, and site visits; the committee analyzed the physical, social, and economic development of the towns as well as conducting post-occupancy evaluations. The authors concluded that the planned company towns they had studied, in spite of the social and economic restrictions imposed by their industrial sponsors, were successful communities. See: Margaret Crawford, Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The Design of American Company Towns, (New York: Verso, 1995), 204

[11] Greg Grandin, Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City, (New York: Picador Books, 2009), 4

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ferris was interested in the role of ‘rules’ such as zoning or those found in research and science, in the development of the city. He states, “…They [The coming generation of Architects and City Planners] will without hesitation or embarrassment assemble and have before them every item of contemporary scientific research, and with these units they will build”. See: Hugh Ferris, The Metropolis of Tomorrow, (New York: I. Washburn, 1929), 60.

The Petropolis of Tomorrow is divided into three sections:

Observations: Garth Lenz, Peter Mettler, Alex Webb

Positions: Neeraj Bhatia, Luis Callejas, Mary Casper, Felipe Correa, Brian Davis, Farès el-Dahdah, Rania Ghosn, Carola Hein, Bárbara Loureiro, Clare Lyster, Geoff Manaugh, Alida C. Metcalf, Juliana Moura, Koen Olthuis, Albert Pope, Maya Przybylski, Rafico Ruiz, Mason White, Sarah Whiting

Projects: Alex Gregor, Joshua Herzstein, Libo Li, Joanna Luo, Bomin Park, Weijia Song, Peter Stone, Laura Williams, Alex Yuen

Visit Neeraj Bhatia's Archinect page for more information, or purchase the text here.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.