The one thing you will not find in school--or even on Architecture Registration Exams--is a course on how to get work, yet it is one of the most basic needs of any design practice. In fact, if you don't have an equal ability to experiment in getting work as you do in doing work you would be fortunate to make it past the first five years.

UpStarts is a series of features on the foundations of contemporary practice. It will have a global reach in which practices from Europe, North America, Asia, and beyond will be asked to address the work behind getting the work, and the effect of cultural contexts. The focus will be on how a practice is initiated and maintained. In many ways, the critical years of a fledgling design partnership is within the initial five years, after the haze and daze of getting it off the ground. UpStarts will survey the first years of practice as a tool for tracking the tactics of the rapidly evolving methods for sustaining a practice.

Archinect editor Aaron Plewke talks to LRA founder and principal Lyn Rice.

AP: How did you come to the decision to go out on your own?

LR: It was more a series of detours and realizations rather than a single decision – and it took 10 years. I was licensed and had been working for eight years before going to grad school at Columbia. After graduating in 1994, I started my own office in New York, Lyn Rice Architect…mostly artist’s lofts and a couple of competitions working out of my apartment. I also freelanced with Stan Allen, Marble Fairbanks, and Ralph Appelbaum to stay afloat, and took a full time position with Diller+Scofidio in 1997. Although I was heavily invested in the work at D+S, I pre-set a two year limit on working there, forcing myself to re-establish LRA by 1999. But when the time came, OpenOffice , a nascent practice conceived of by Alan Koch and Linda Taalman, asked if I was interested in joining them to interview for Dia:Beacon . It was a definite long-shot, but we did get the job and at Dia’s request, immediately formed a partnership. Late in 2002, Linda and Alan left for LA to form Taalman Koch Architecture , so OpenOffice went from four partners to two, Galia Solomonoff and me. OpenOffice had been conceived of as a loose affiliation of architects that would collaborate on an as-needed basis, so forming a partnership was in large part antithetical to the whole idea, and late in 2004, Galia and I dissolved the office to start independent practices.

Dia:Beacon , Photography © Richard Barnes

Dia:Beacon , Photography © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

Dia:Beacon , © David Joseph

AP: Dia:Beacon is a significant project for a young practice. How were you and your partners at OpenOffice able to get the initial interview? Why do you think the Dia Art Foundation ultimately selected your team?

LR: In 1999, New York was in an optimistic pre-millennium moment and a generational shift was taking place from the singular heroic or corporate offices to young multidisciplinary practices. Dia was intrigued by House x Artists , a project Linda and Alan had initiated a year before, and especially by the concept of OpenOffice. Dia’s director, Michael Govan, asked if they could assemble a team capable of completing such a project. They had recently met Galia Solomonoff, a former classmate of mine at Columbia, who asked if I would join them in pursuing the project. Energized by Dia’s proposition, we quickly worked to familiarize ourselves not only with the project, Dia’s history, the collection and its requirements, but also with eachother’s way of working. In May, we had our first interview with Govan and curator, Lynne Cooke, to discuss the project and a possible collaboration with Robert Irwin .

Subsequently, as Dia consulted with other more established architects, we submitted a proposal for the project and met with Robert Irwin. All four of us had experience working with artists and museums, and we were interested in having our ways of thinking about architecture challenged - contaminated by the completely different way artists work and think. Irwin's comfort level was important to Govan and Cooke. Govan believed that we could do the project and felt that our youthful dedication and our desire as architects to collaborate with Irwin would be necessary assets for the project (Irwin had recently completed gardens for Meier’s Getty). As it turned out, the positive chemistry we experienced at that initial meeting with Irwin endured throughout the four years designing and building Dia:Beacon.

[AND]SCAPES , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

[AND]SCAPES , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

AP: Can you elaborate a bit on the concept of OpenOffice? What are the merits and flaws of this model of practice?

LR: The idea is to create a flexible, fertile platform for collaborative alliances which are able to address the needs of specific projects. The intention is to incorporate into architectural discourse the influence and dialog from sources outside the discipline proper. By engaging with artists, philosophers, writers, scientists, etc., the norms of architectural thinking are disrupted/expanded to encourage unexpected, hopefully innovative results.

There a couple of practical limitations that restrict the ability to sustain this model. First, patrons/clients of substantial projects tend to require a single legal entity with which to establish an Agreement. This means creating a not-as-nimble, not-as-prolific “permanent” partnership between parties which may be most productive in a temporary project-based alliance, or series of alliances.

Secondly, by declaring the office’s openness to collaborate on projects, a misreading of the office as a sort of creative service organization can emerge. Ironically, the office’s intentionally constructed identity as a “collaborative” – its innovation – can cloud the practice’s architectural acumen. By comparison, LRA is a platform for a range of building, planning, art and cultural research projects that keeps clear our identity as architects, but maintains our ability to collaborate on a project-by-project basis.

AP: How seamless was the transition from OO to LRA?

LR: I had been working closely with Astrid Lipka (now associate principal at LRA) since 2000, and her decision to come with me to help build Lyn Rice Architects, along with Anne-Rachel Schiffmann, was significant to maintaining consistency with existing projects. We started out with a couple of small projects and a larger one under review and with an uncertain future. We were lucky enough in our first three months to be invited to do a programmatic speculation for the New York Times Magazine and win a competition for a pavilion installation at a museum in Tulsa, for which we received some press. I was teaching at Cooper Union also, which meant additional support for the office.

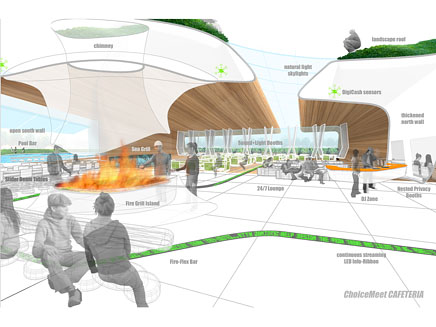

ChoiceMeet , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

ChoiceMeet , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

Parsons Infill Tower , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

AP: Did that larger, uncertain project turn into a commission?

LR: That was the New School project which was already a commission we had won at OpenOffice with the work of Leif Halverson and Astrid. The client was exploring all of their options, including the possibility of constructing a new building that would maximize the site’s zoning envelope, so we were acting more as planners than designers at the time and did not know what the outcome would be. Ultimately, the new building project did not go ahead, but fortunately, the Johnson Design Center , a street level renovation, did.

Parsons Sheila C. Johnson Design Center , Photography © Michael Moran

Parsons Sheila C. Johnson Design Center , Photography © Michael Moran

Parsons Sheila C. Johnson Design Center , Photography © Richard Barnes

Parsons Sheila C. Johnson Design Center , Photography © Michael Moran

Parsons Sheila C. Johnson Design Center , Photography © Richard Barnes

AP: I guess the Johnson Design Center is technically a "street level renovation," but that strikes me as an understatement, considering the apparent scope and complexity of the project.

LR: That’s right – each day brought new challenges to the project. With an existing one story maintenance shop clogging the geographic center of the complex, we realized we had the opportunity to remove that structure, open up the facility, and connect all the programs via a new glazed-roof campus quad. Typically, campus planning precedes campus building, but this quad came 90 years after the completion of the buildings in a tactical appropriation. We were also fortunate to be able to expand the project downward and scoop out a new cellar to house a new chiller plant with the capacity to air-condition all twelve floors above – this also provided new links between buildings at the cellar level. There were many existing conditions and alterations that were hidden by decades of accumulated finishes. They were also hiding opportunities for The School to do more – like join the West 13th lobby with the Fifth Avenue lobby. The first floor of Parsons’ 66 Fifth Avenue building was added to the scope and so we were then working with all four buildings, each constructed at a different time using different construction techniques. Designing and building within these structures was an architectural, structural, and mechanical challenge – like being a veterinarian operating on four distinctly different, live (the buildings remained open during construction) animals simultaneously.

AP: How do you go about getting new work? Do most projects come in through the relationships that you've built during your time working in New York? Do you have to engage in any sort of marketing?

LR: Usually through previous clients (especially in exhibition design) or through invitations or RFPs – and yes, most projects do come through our New York relationships. We have stayed away from open competitions because of the expense and because the odds are too long. When a client takes the time to identify LRA as part of a specific group architects whose work they are interested in, and they request proposals from that list, it means 1) that they are knowledgeable and are operating with a point of view, and 2) that they are already seriously considering us. It is a much better scenario, though the competition is always tough. We have pursued around 9 RFPs in the last year. We were awarded two projects, and shortlisted on five others. It is expensive to respond, but even if LRA is not selected, we get the opportunity to meet new people and familiarize them with our office – and that exposure has led to new projects. Primarily because of our size, we do not have a marketing team or strategy other than remaining open to all project types. And we push each project beyond expectations, and keep them in budget and on time…that helps build a happy client base. Potential clients always check recommendations, so we focus on satisfying the clients we have currently, rather than at looking for new ones.

Beyond the Catwalk , Photography © Frank Oudeman

Beyond the Catwalk , Photography © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

AP: What do you have on the boards at the moment?

LR: We are juggling a range of projects at the moment…there are two projects for the city in which we are in preliminary phase work: a Carriage House on Staten Island (our first ground up project in NYC) and a wayfinding/districting project for the Long Island City Cultural Alliance (both part of NYC’s Design Excellence Program ). We are finishing up design work on two residences: one, a 10,000sf Inner-Mongolian villa (part of Ai Weiwei and Herzog & DeMeuron's Ordos100 Master Plan), and the other, a residence upstate in Columbia County for a local fashion designer. We have several exhibition projects - an exhibition planning project for the National Building Museum in DC, and two exhibition design projects for upcoming shows at the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois. We are also in the preliminary phases of work on a vision plan for the the Krannert . We have two additional small projects under construction at The New School – a lobby space and a classroom fit-out.

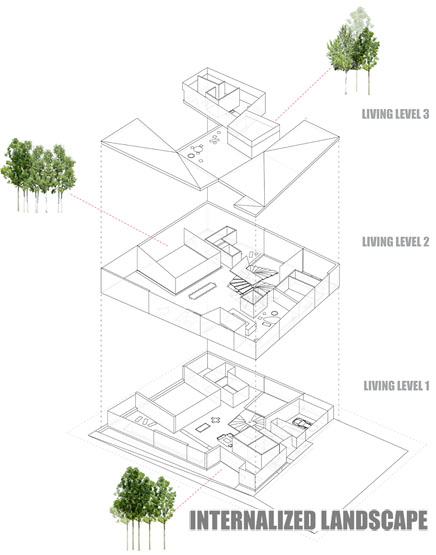

Villa 007 , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

Villa 007 , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

Villa 007 , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

Villa 007 , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

AP: I'm interested in the fact that this diversity of projects and client types is such a fundamental aspect of your practice. Is this a fortunate case where a practice's creative agenda results in a business model that's well-positioned to deal with fluctuating markets?

LR: We absolutely embrace diversity in project type, speed, scale – the more broad our practice, yes, the more likely we will be able to maintain a full workload. We refer to the office as an “architectural platform” in a neutral, agenda-less way that withholds judgment and seeks opportunity without regard to project type. That said, the term “agenda” implies that we intentionally sought and selected this diverse range of projects. In fact, they have come along much by chance – each a new project type, each filling in a gap in our body of work. We have been offered such a range of projects and we have happily taken these projects on – however small – just to have the opportunity to establish new relationships with interesting people and institutions. So in addition to these different, inconsistent project types accumulating, we gain an expanded client base – an absolute necessity in supporting the platform.

AP: Can you compare what it's like to work with these different types of clients? I recall a comment you made in a New York Times article that the Ordos100 villas have very little client restriction, whereas I imagine your institutional clients bring myriad constraints to a project.

LR: Yes that is true…many constraints. I was pointing out in the Times that the Ordos 100’s streamlined process – speedy schedules, few client restrictions, and freedom from producing construction documents – appears to be a dream project of super-efficiency. But in what Sarah Whiting, Bob Somol and others have referred to as projective practice , examining projects constraint and mining them for architectural opportunities leads to unexpected, practical results…without these constraints, we feel naked. Against what shall we push and what norms do we challenge? Often, solving the pragmatic issues in the project leads us to innovate.

We are working for New York City on a project which is completely under-funded, so the driving restriction is the budget…we spend our time researching all building technologies for the least expensive and then work to build something playful, but practical with it. There are also many agencies involved, which involves a different kind of constraint.

The New School Welcome Center , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

With the Parsons project, The New School is an amazing supporter of our work – they took advantage of the opportunities that these difficult existing buildings presented. They are very smart with many stakeholders, but each with a specific expertise. They invited us to present the work to each group, keeping us involved in all the decision-making processes, and this direct access/communication was key to the success of the project. Their concern was getting use out of every space and together we reprogrammed the street level of four buildings…it is exhilarating to see these spaces now filled with students.

We are designing a bathroom for a famous art critic, and both space and economy are our constraints. We made a matrix of possible interventions and had lively discussions about them. We are now working to combine the best attributes of most desirable schemes…it is an experiment on a different scale but no less stimulating…and more intimate.

The New School Welcome Center , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

At the Krannert Art Museum, we work with the director and she, more than any other client, knows how to apply pressure to us. Often we react to specific client demands and schedule…she simply says that we are wonderful and that she knows we will do a great job. This is really frightening and we immediately get to work trying to live up to this expectation.

Here in New York, we are also working for our engineers on their offices, which is like working for family…all parties are so familiar that an extra effort must be made to keep the project run professionally because we want the best possible result architecturally and there is a good deal of money at stake. All of these relationships take time to build and a good deal of trust to maintain.

Buro Happold New York , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

Buro Happold New York , Image © LYN RICE ARCHITECTS

AP: What do you think the next five years holds for LRA? How do you plan on approaching the development of your practice?

LR: I once was interviewing an intern candidate who asked to see our five year business plan, so he could better assess LRA. I told him I did not have one…not even for one year. He was uneasy with this nonchalance and decided that a summer with us was not such a good investment of his time.

WorkAC ’s stated five year plan …say yes to everything ...appeals to us and is very nearly how we have been operating for the last four years. While we are grateful that projects have come to us despite having no marketing plan whatsoever, we suspect that this approach is ultimately not sustainable. We respond to RFP’s aggressively, but we want to develop a more proactive approach in cultivating new work. We want to deepen our connections with other like-minded thinkers/disciplines through collaborative efforts. And we would like to pursue public, arts, and academic/institutional projects that will specifically build on our body of completed work…to actually seek out these project types. This is common practice to all sensible businesses, but new for us.

Anticipating a new level of economic sobriety in the US, we need to be able to maintain our design team and offer stability through what could be lean times – and we want to do it by approaching business as a project itself. Why not embrace constraint in the business-project, too? Perhaps that will also lead to innovations in the way we work. We have to take advantage of the efficiencies associated with our increasing know-how , but keep experimenting in the way we pursue, organize, analyze, and complete projects. So while we will keep saying yes to the diversity of project typologies that expand/stimulate our practice, we will work to more actively seek out projects and opportunities that directly build on LRA’s primary interests, strengths, and experience.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

Aaron Plewke is an associate at Deborah Berke Partners. He designs and manages projects in all sectors, distilling each client’s needs into unique, transformative solutions. Aaron began practicing architecture in 2005 and has worked in Florida, St. Louis, and New York, on projects ...

4 Comments

This just in...

Couple to give $45 million for new LACMA pavilion

The new Lynda and Stewart Resnick Exhibition pavilion was designed by architect Renzo Piano to complement its neighbor, the Broad building, which opened this year. The couple will give about $10 million more in artwork.

Govan likened the new pavilion in some respects to the Dia: Beacon building, the former Nabisco factory on the Hudson River that was converted into a museum during Govan's tenure as director of the New York-based Dia Art Foundation.

"Here's the beauty of the building," Govan said of the Resnick addition. "It's all skylights. So there's the wow factor."

~~~

Why not they didn't give the pavilion design to LRA? They seem to deserve it after-all.

But then again, it is nice to have your work to set up an example and somebody say, "play it like this Piano."

LA Times Story

AP,

Nice dialogue/interview..Perfect addition to the Upstarts feature...

I wonder if all new(ish) firms need to take the WorkAC approach to a 5 year plan.

Say yes/take everything. It doesn't seem as most practices early on are capable of saying no, at least from a financial perspective. Unless they have teaching gig's on the side. And even then...

the don't say no approach was certainly our way. unfortunately that means something diff in louisville vs ny. we had to do some work that really shouldn't have been done...by anyone.

just realized i met lyn, oddly enough, about 10-11 yrs ago, when he was at d+s. i think i stayed in his apt. kinda cool.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.