Our education is based upon the Classical education. An architect is a mason who has learned Latin. Modern architects seem, however, more likely to have mastered Esperanto.

Adolf Loos, “Grundsätzliches von Adolf Loos,” Adolf Loos (Vienna: 1930), p. 17.

In our world of powerful stimuli and the often irresponsible, commercially motivated love of experimentation for its own sake, there is a great deal that does not establish real communication. For intoxication alone cannot insure lasting communication.

Hans-Georg Gadamer, The Relevance of the Beautiful (UK: 1970), p. 51.

The art of building has been transformed into a business of self-display and promotion through the design and construction of figurative motifs, making it an object of consumption.

David Leatherbarrow, The Roots of Architectural Invention, (UK: 1993), p.1.

...continuation of the essay's Part 1 recently published on Archinect...

Communicative Architecture

Venturi and Scott Brown’s inclination toward ‘generic and conventional space’ over ‘heroic space’ should be connected to what Loos said about ‘the form given through tradition’ and also what he was battling against in his time. xvi According to Aldo Rossi, “What Loos is really attacking in his contemporaries is not so much their style or their taste, even though he finds it abominable, what he cannot tolerate is the ‘redemptive’ value that they assign to their own actions.” Loos thought that “Modern architects have always tried to assign this redemptive value to what they have done.” And as a sort of final response to all this, Loos wrote, as though in an obituary, “We know that all the artistic fuss over style of living – in any country – do not make the dog move away from the warmth of the stove, and that all the traffic of associations, school professorships, periodicals, exhibitions, and so on has not produced anything new.” xvii Against this redemptive, “will to art” manner, Loos urged the architects to put aside their individual ambitions for the sake of collective coherence. He wrote: “the best form is there already and no one should be afraid of using it, even if the basic idea for it comes from someone else. Enough of our geniuses and their originality. Let us keep on repeating ourselves. Let one building be like another. We won’t be published in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration and we won’t be made professors of applied art, but we will have served ourselves, our times, our nation and mankind to the best of our ability.”xviii

Loos was concerned with the well-being of people. According to Ludwig Munz, “He wanted to build for human beings, who felt the need, however little money they might have, to be ‘at home’ in quiet communion, people who, for their well-being, needed to be alone and able to concentrate. Everything he stood for, even the lack of decoration on his buildings and their smooth walls, signified to him only a means to give people time for the nobler pursuit of life”.xix

In “The Principle of Cladding”, Loos stated flatly that “[the] architect’s general task is to provide a warm and livable space. Carpets are warm and livable. He decides for this reason to spread one carpet on the floor to hang up four to form the four walls.” If this were about the content of communication, the latter part of the same paragraph, “But you cannot build a house out of carpets. Both the floor and the tapestry on the wall require a structural frame to hold them in the correct place. To invent this frame is the architect’s second task,” would be about the method of communication, if we can see through the metaphor and understand that he is talking about a structure that communicates.

According to Gadamer, as a witness or someone who experiences art, one needs to discover the “autonomous time” proper to the form of art. He called this the “inner ear”. In the case of rhythm, we can only hear it if we ourselves introduce the rhythm into it. In the case of architecture: “Our contemporary forms of technical reproduction have so deceived us that when we actually stand before one of the great architectural monuments of human culture for the first time, we are apt to experience a certain disappointment.” xx Gadamer explained that we are disappointed because the building does not look as painterly as in a photo, and argued that we have to go beyond considering architecture as an image and actually approach it in its own right, meaning that we have to go up to the building and walk through it, both inside and out to truly understand it. This is finding the appropriate autonomous time, and learning to “decipher” the piece of art through it.

When I look at the art piece by Robert Rauschenberg, I sense myself trying to understand what it is trying to say, while filling in the blanks: the cloud above JFK – or perhaps a dark halo – may symbolize his death, and the reproduction of his hand could be something about the media. (Figure 15) This act, Gadamer says, is the involvement of the spectator in the making of art. The art becomes via participation. Conversely, I have a harder time ‘deciphering’ Frank Stella’s work. (Figure 16) Is there a scale of communicability or accessibility at issue here? In other words, does the representation in art ever escape our grasp because it is too abstract?

And according to Heidegger, the symbolic is the interplay of showing and concealing. It is this philosophical insight of showing and concealing in art that denies the idealism claiming a total capture of meaning. It implies that there is more to the work of art than a meaning that is experienced only in one way in the final moment of interpretation. According to Gadamer, this is the “additional meaning” in art, and what makes art irreducible.

Communicability of architecture is facilitated by the comprehensibility of its content – effects, for Loos – to spectators or witnesses. Loos stated that these effects can be carried out via choice of materials for cladding. He seems to be talking about atmosphere or mood-making in architecture through materials that engage the witnesses and evoke certain emotions in them: wood and carpet for warmth, stone for authority and luxuriousness, and metal for security, etc.

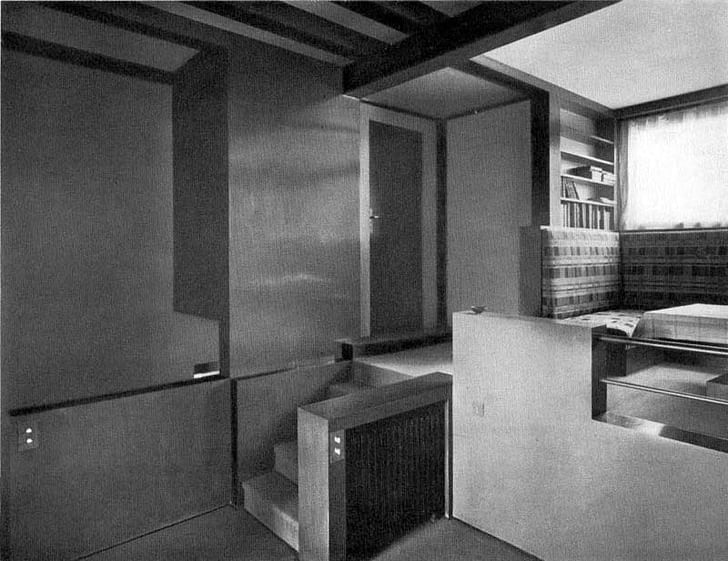

Others have observed that in Loos’s buildings, psychological interplays are organized via spatial qualities and arrangements. According to Beatriz Colomina, inside of Loos’s houses: “Upon entering, one’s body is continually turned around to face the space one just moved through, rather than the oncoming space or the space outside. With each turn, each return look, the body is arrested”. She further described this through the Moller house: “There is a raised sitting area off the living room with a sofa set against the window. Although one cannot see out the window, its presence is strongly felt. The bookshelves surrounding the sofa and the light coming from behind it suggest a comfortable nook for reading. But comfort in this space is more than just sensual, for there is also a psychological dimension. A sense of security is produced by the position of the couch, the placement of its occupants, against the light. Anyone who, ascending the stairs from the entrance, enters the living room, would take a few moments to recognize a person sitting in the couch. Conversely, any intrusion would soon be detected by a person occupying this area, just as an actor entering the stage is immediately seen by a spectator in a theatre box.” xxi (Figure 17) This is the psychological dimension provided by the Raumplan. Comfort in this space is related to both intimacy and control.

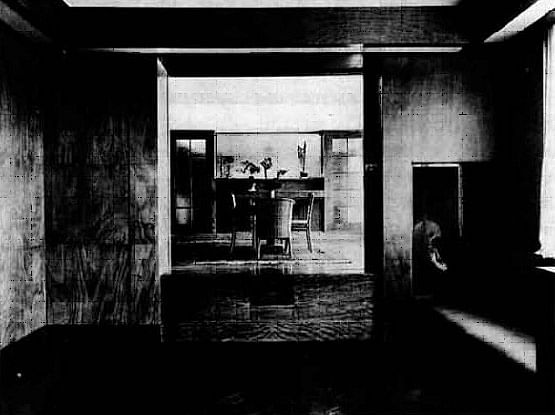

The theatricality of Loos’ interiors is also set up by breaking down the condition of the house as an object by convoluting the relationship between inside and outside. Mirrors are one of the devices he uses. In the dining room of the Steiner house, the window here is only a source of light. The mirror, placed at eye level right below the opaque window, returns the gaze to the interior. The reflection in the mirror is also a self-portrait projected onto the outside world. (Figure 18) The placement of the mirror at the limins between interior and exterior undermines the status of the boundary as a fixed limit.

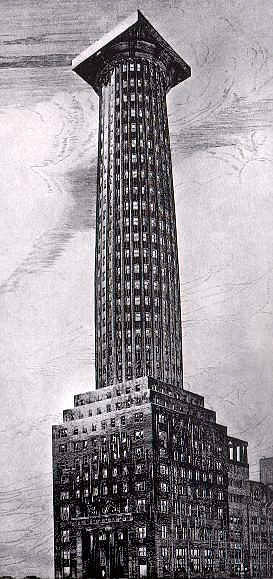

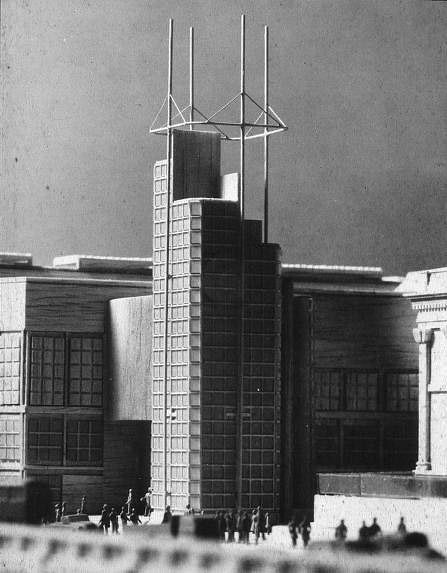

Colomina writes: “This ambiguity between inside and outside is intensified by the separation of sight from the other senses. Physical and visual connections between the spaces in Loos’ houses are often separated.” xxii In the Moller house, there seems to be no way of entering the dining room from the music room which is about 2.5 feet lower. The only means of entry is by the steps hidden in the timber base of the dining room. (Figure 19) This strategy of physical separation and visual connection should be connected to what Heidegger and Gadamer meant by ‘revealing and concealing’ in art. However, in Loos’s architecture, this revealing and concealing is not only limited to the visual: it also happens through the openings that are screened by curtains, in which case visual connection is replaced by sense of sound perception; repetition of forms and materials, where residual memories of them become symbolic; and chance encounters and their unexpectedness. And it takes place in his “speaking architecture” via the symbolic use of architectural elements as well. According to Munz, in using classical elements of architecture, “Loos penetrates to a much deeper layer, into the sphere of symbolism, where columns have a certain acceptation: they are a sign of nobility.” This is employed in his design for the Chicago Tribune Column – is this a column or an occupiable building? (Figure 20)

The design for Chicago Tribune Column at once confuses us and confirms his intent through this clear ambiguity. It certainly has an outward effect which is radically different from the exterior of the domestic buildings which are designed from inside out. (Figure 21) In fact, when Loos wrote about the exterior of the building he was not only quite dogmatic about the division between inside and outside, he also said that that “the house has to look inconspicuous,” arguing that “the house does not have to tell anything to the exterior; instead, all its richness must be manifest in the interior.” Colomina saw this as a contradiction between his writing and design, but perhaps the ‘telling nothing’ or ‘speaking through silence’ on the outside is still connected to the decorum and the appropriate effect, only this effect is a quiet gesture of meditative participation rather than a loud statement. This is not unlike what I have argued for in explaining the varied facades of Venturi and Scott Brown’s Sainsbury Wing Extension. Loos also wrote about this in precisely such terms: “We have become more refined, more subtle. Primitive men had to differentiate themselves by various colours, modern man needs his clothes as a mask.” xxiii (Figure 22)

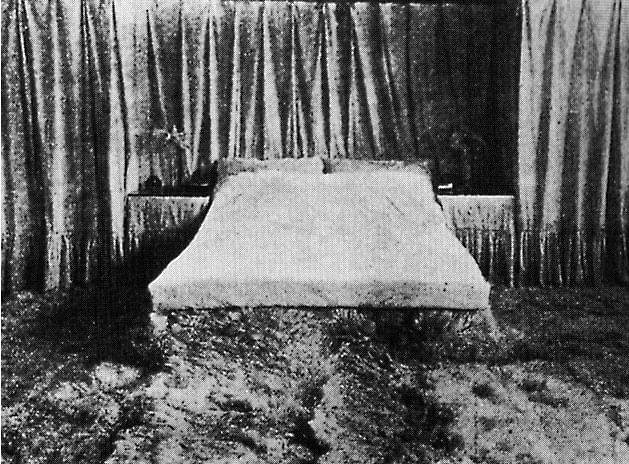

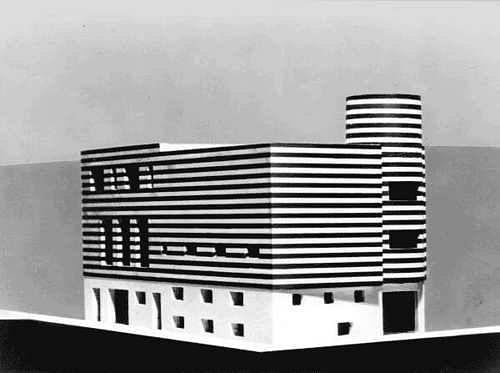

For him, fashion or cladding, is a mask which protects the intimacy of the metropolitan being. Therefore the argument of polarity too often used to describe the ‘warm domestic interior’ and the ‘cold metropolitan façade’ of Loos’s works should now be replaced with a reading that for every space there is its own decorum. There is not a ”split wall” that simplistically divides the inside from the outside in Loos’s architecture, instead, there exist intricate layers of decorum that characterize each space – what is appropriate for the exterior, the living room, the dining room, and the bed rooms. These layers of appropriateness are interlocked in a complex composition as their spaces are. And the content of this communication, or the spatial “effect”, is the architecture as we feel it. Like in Lina Loos’s bedroom, a private interior space can contain something warm that wraps around, while another – an indoor swimming pool - can hold a body of cool water. (Figure 23) Then there is also the notion of outward effect -- “speaking architecture” -- as in the case of Josephine Baker’s house, of which effect made Munz, an otherwise careful writer, begin his assessment of the house with the exclamation: “Africa: this is the image conjured up more or less firmly by a contemplation of the model.” xxiv (Figure 24)

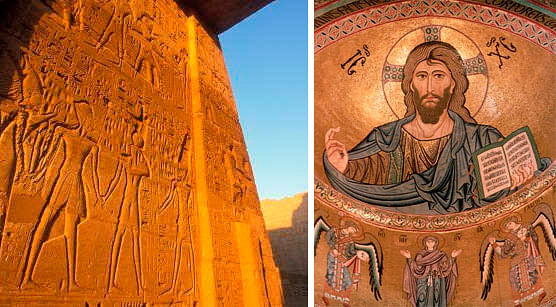

Venturi and Scott Brown argue that the concept of function in architecture should be broadened to include communication – architecture as language. They promote architecture that clearly acknowledges, engages and accommodates symbolism and iconography, emphasizing architecture’s historic function of communication and information. This communicative aspect seems to be often rendered ambiguous or lost in the abstract forms of some recent Neo-Modernist and Deconstructivist architecture. "As a method of analyzing texts based on the idea that language is inherently unstable and shifting”, Deconstructivist architecture detaches certainty from its communicative aspect. xxv Venturi emphasizes the lessons learned from the historic and social relevance of the hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt, the mosaics of the Byzantine and Early Christian Churches, and the stained glasses of Gothic architecture, all of them now considered fine art, but originally intended to communicate religious content. xxvi (Figure 25)

In the Sainsbury Wing Extension Project, the monumentality observed in other museums designed and built around the same time – Richard Meier’s J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, and also in the original scheme proposed by Ahrends Burton and Koralek Architects - was avoided in favor of focusing more on aspects of urban relationship and appropriate scale, and on aspects of the symbolic. (Figure 26) David G. De Long writes, “The building was indeed a grand yet unpretentious gesture… Here the firm made art of context, finding meaningful expression through its symbolic representation. This has nothing to do with simple replication, but rather with intelligent interpretation, with distortions and unexpected juxtapositions of shape and scale, all recognized as means of twentieth-century artists. The feathering, or gradual diminution of applied detail, is critical as well. It helps reveal the representational nature of the imagery and aids in deconstructing what could otherwise be seen as regular geometry, steadfastly avoiding numbing, life-constricting prettiness.” xxvii And the effect is clear, as Sylvia Lavin has observed: “The whole is an inversion of the Modernist notion of transparency: one does not simply see through to the interior or its structure, but through the revealingly transparent collage of the exterior, one sees and understands the surrounding context.”xxviii

For Venturi and Scott Brown, this notion of ‘wholeness’ is important, and it is also a specific kind: the difficult whole through inclusion rather than the easy unity through exclusion. Venturi writes in his Complexity and Contradiction: “The difficult whole in an architecture of complexity and contradiction includes multiplicity and diversity of elements in relationships that are inconsistent or among the weaker kinds perceptually... The ‘difficult whole’ can include a diversity of directions as well.” Venturi and Scott Brown’s argument for an architecture of difficult unity that considers a perceptual whole the result of, and yet more than, the sum of its parts, should be connected to the additional meaning of revealing and concealing in art. xxix And their call for inclusion of diverse elements also draws a parallel with the integration of highly diverse settings in Raumplan. In fact, Loos, Venturi and Scott Brown have all learned from the Arts and Crafts movement. The buildings of Edwin Lutyens in England and those of Richardson in the United States were great inspirations for Loos’s concept of interlocking spaces and sensitivity to integrated differences. xxx Venturi mentions Lutyens several times in his Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, finding in his houses a delightfully accommodated combination of ambiguities, tensions, and contradictions, where willful deceptions of inner and outer arrangements; sudden shifts of scale and orientation; altered architectural elements and fragments were used to symbolic effect.

It is important to acknowledge that this call by Venturi and Scott Brown for inclusion in an architecture of complexity and accommodation is different from Walter Gropius’ dream of the “complete building,” a dream that “amounts to a subjection of the demands of life to the demands of aesthetics.” xxxi (Figure 27) Far from subjecting life to aesthetics, Venturi and Scott Brown call in Learning from Las Vegas for embracing life’s punches in the attempt to set a new equilibrium between firmness, commodity and delight. They recognize variety in society and in the cityscape as creating tension that promotes many levels of interpretation and resolves in a unity. Venturi suggests that modern architecture should look to and learn from the everyday landscape to draw the complex and contradictory order that is valid and vital for our architecture as an urbanistic whole. xxxii And his argument against the “prim dreams of pure order” imposed in the easy Gestalt unities of the urban renewal projects of establishment Modern architecture, again, echoes Loos’s criticism of the redemptive architectural practice.

According to Reyner Banham, the Smithsons’s description of the process of ‘as found’ was also not an aesthetic but an ethical concern. xxxiii Indeed, Peter Smithson wrote: “There's a little school on the corner, Bousefield School, where a landmine was dropped on Beatrix Potter's house. How is it that you can train an eighteen-year-old to drop a bomb on Beatrix Potter's house? It is unimaginable. I mean – incredible cruelty propounded as normality. If you can't imagine the condition of that boy who dropped the bomb, you can't also imagine the period of ‘as found’.” xxxiv For the Smithsons, New Brutalism was perhaps a refusal to forget the recent tragic past, and to stand in a constant protest against the forgetfulness of postwar optimism. But it was also never only an aide-mémoire of the historical past: it was devoted to discovering a new social aesthetic that might be able to accommodate people's wishes and memories after the war. xxxv The Smithsons were also dealing with a socio-ethical dimension through their works.

Toward the Difficult Whole Again

The last words of the late Zen teacher to his pupils were: “Do not worry. The mountains will always be green again, and the rivers will always flow with water. It is not a road that comes and goes, appears and disappears at random. It will always be there as it changes.” By ‘road’ he meant the world. And by ‘worrying’ he meant the struggle and anxiety in staying in the orientation toward the Truth. As we have learned from Heidegger, we are thrown into a world, in the midst of something that is part of us but also exceeds us. The anxiety comes from this being thrown into something that one has no control of. But we can relax a little bit about the ‘geworfenheit’ or being caught up in what exceeds us, when we realize that the world is not going anywhere. It will always continue – continue through change. There is nothing more permanent than the fact that it will always change, and the change is into something similar. So the continuity through similitude is always there and we are part of it: existence is continually contextualized. And the self-projection, or ‘you are what you are because you are outside of it’, is the excess Gadamer spoke of and what we see in architects’ works.

For Loos, ‘being here, therefore everywhere’ was not simply a product of nationalism or historicism, but related more to the issue of ‘locatedness’. This notion of social participation was very important to him, as we can also see in his inclination toward the sense of decorum over decorative art out of one’s era. And the purpose of the socio-ethical dimension of Venturi and Scott Brown’s works is outlined in the introduction to the second edition of their collaborative book, Learning from Las Vegas: “…to learn a new receptivity to the tastes and values of other people and a new modesty in our designs and in our perception of our role as architects in society.” xxxvi The symbolic effect of their work resolves in a social wholeness.

In an era easily seduced by exotic forms and materials, when, ironically, bridging the two in architectural design still seems difficult, what does it mean to be ethical in building and making, and also being civic? What does it mean for architecture to participate in the making and continuing of a society?

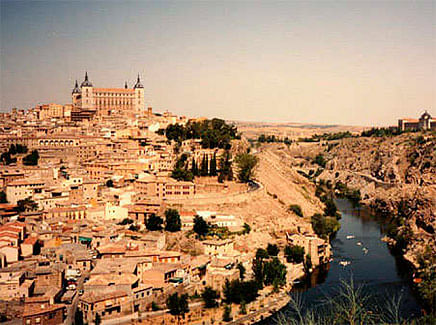

Perhaps it is still about being in the world with others. In the essay, “Shifting Paradigms: Renovating the Decorated Shed,” [2008] I argued that the development of communication technology and personal sensory gadgets such as the internet and smart phones have provided society with altered spatial perceptions and possibilities of accommodation through architecture. Its social impacts are rich. Simple but sweeping changes can come from, for instance, being able to share personal experiences, in real time, with friends thousands of miles away. It can de-materialize physical boundaries and re-establish lost connections, starting with those closest to us and reaching out to include ever-widening circles of friendship. (Figure 28) Additionally, the rapid densification of population in urban areas today causes an economic necessity to reevaluate the importance of efficiency and mutual ‘sharing’ of space in architecture. ‘Shifting space’, a method of arranging spaces that I suggested in the essay, is an effort in this vein. It is a way of discovering a function which is a common denominator of surrounding programs, then allowing it to shift freely between occupancies. The sharing of common functions in the interstitial space will not only maximize usage of the area, but also bind together the lives of diverse occupants that are otherwise unlikely to overlap. xxxvii Being in the world is understanding each other in the midst of multiculturalism and it can also mean restoring and broadening a more inclusive meaning of ecology, not only as something to be “fixed” via sustainable technology. Yet a question remains: can composition of such wholeness be aimed at in art? Jean-Luc Marion’s argument for the saturated phenomenon suggests the impossibility of representing something that unceasingly exceeds us. xxxviii But can it be claimed that our continuous efforts to assimilate and approximate this sense of wholeness through art is imaginably what Michelangelo meant by “the way of the truth,” that is, in a paradoxical manner even truer than the truth itself? If truth is in the orientation toward itself, and if indeed “what the book is to literacy, architecture is to culture as a whole”, possibly one such effort can be found in Toledo, Spain. xxxix (Figure 29) In an area of given historical cultural and religious conflicts, there is somehow a sense of harmony, in finding ways to live with one another despite the differences and disagreements. And how about Los Angeles, where Banham, in 1971, saw extraordinary amalgamations of geography, climate, economics, demography, mechanics and culture contrive to co-exist? xl (Figure 30) It is not unlike the concept of marriage, the joining of families and communities, and our long history of continuous and combined efforts to make it work. The Mudéjar architecture of Toledo, and the “excessive tolerance” included in the extremes of Los Angeles speak to us poetically about open-mindedness, acceptance, and also something about the good will – Plato’s ‘eumenes elenchoi’ - and finally, the difficult whole through inclusion rather than easy unity through exclusion, in its broadest definition.

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

My appreciation to Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, David Leatherbarrow, Arthur Lubetz, Anne Lutun, Aaron Forrest, Sun-Young Park, Yong-gao Shi, Jiwon Choi, Yoonwhe Leo Moon, Pil-bae and Heekyung Song for their advice, inspiration and criticism in the writing of this essay. Also to Martin Hershenzon, Eric Bellin, Ariel Genadt, Tony Caicco, Bonnie Cate Kirn, Rebecca Ann Jee, Jade Heshmatpour, David Nix, Jen Tobias, Laura Lo, Jacquelyn Santa Lucia, Melody Rees, Arthur Azoulai, Diego Taciolli, Tyler Wallace, Dane Zeiler, Darren Taylor, Yamada Yohei, Ikje Cheon, and other colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania with whom I struggled together in the development of the topics discussed here.

xvi Venturi, Robert and Denise Scott Brown, "Signs and Systems for a Mannerist Architecture for Today," Architecture as Signs and Systems: For a Mannerist Time, p. 218.

xvii Rossi, Aldo, "Introduction," Adolf Loos, Spoken into the Void: Collected Essays 1897 - 1900 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982), p. xiii.

xviii De Botton, Alain, The Architecture of Happiness, (New York, NY: Pantheon, 2006), p. 183.

xix Munz, Ludwig, Adolf Loos (New York, NY: Praeger, 1966), p. 31.

xx Gadamer, Hans-Georg, The Relevance of the Beautiful (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 45.

xxi Colomina, Beatriz, "The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism," Raumplan Versus Plan Libre: Adolf Loos to Le Corbusier (New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1988) p. 33.

xxii Ibid., p. 36.

xxiii Ibid., p. 38.

xxiv Munz, Ludwig, Adolf Loos (New York, NY: Praeger, 1966), p. 195.

xxv Besley, Catherine, Post Structuralism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

xxvi Venturi, Robert, "Architecture as Signs rather than Space," Architecture as Signs and Systems: For a Mannerist Time, pp. 93-101.

xxvii Brownlee, David, David G. De Long and Kathryn B. Hiesinger, Out of the Ordinary (Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001), P. 130.

xxviii Ibid.

xxix Gadamer, Hans-Georg, The Relevance of the Beautiful (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 34.

xxx Leatherbarrow, David, The Roots of Architectural Invention (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 133.

xxxi Harries, Karsten, "Thoughts on a Non-Arbitrary Architecture," Dwelling, Seeing, and Designing: Toward a Phenomenological Ecology, (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993), p. 43-44.

xxxii Venturi, Robert, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1966), p. 104.

xxxiii Ibid., p. 168.

xxxiv Highmore, Ben, "Rough Poetry: Patio and Pavilion Revisited" Oxford Art Journal, Volume 29, Issue 2 (June 2006). P. 269-290.

xxxv Ibid.

xxxvi Venturi, Robert, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1972; revised edition 1977), p. xvii.

xxxvii Song, Steven, and Sun-Young Park, "Shifting Paradigms: Renovating the Decorated Shed," http://www.archinect.com/features/article.php?id=75248_0_23_24_M. In 2007-8 Steven Song and Sun-Young Park wrote the article in collaboration with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown.

xxxviii Horner, Robyn, Jean-Luc Marion: A Theo-Logical Introduction (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2005), P. 113.

xxxix In his 2004 book, Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation, Vesely argued that restoring the communicative role of architecture is a necessary step toward restoring its role as the topological and corporeal foundation of culture.

xl Banham, Reyner, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2000), p. 7.

Steven Song is a young architect who has practiced with VIUM, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Arquitectonica, Urban Design Associates, and Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates. In 2007-9, he collaborated with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown on "Shifting Paradigms : Renovating the Decorated Shed," an essay which adapts their earlier thesis to address the changing conditions that young architects today will face. "Architecture in the Givenness : Toward the Difficult Whole Again" is about principles in architecture that persevere: the orientation toward the truth in architecture is toward an understanding of what it means to be in the world, in harmony, with others. The essay suggests that our version of the ‘difficoltà’ is the participation in the dialogue of the open society through the difficult, inclusive composition of ‘being here, therefore everywhere’ rather than the easy unity through exclusion.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.