“I spent 50 years at HOK, working my way up from junior designer to CEO,” Patrick MacLeamy wrote in his 2020 book Designing a World-Class Architecture Firm: The People, Stories, and Strategies Behind HOK. “Where else can you do that?”

During his time as HOK CEO and Chairman from 2003 to 2016, MacLeamy exerted great effort in shaping a resilient practice that, in many ways, harks back to the ethos of the firm’s founding. As a child of the Great Depression, co-founder George Hellmuth purposely structured HOK along the principles of what he described in 1944 as a 'Depression-Proof Firm,' one that could step off the typical economic rollercoaster that many firms, then and now, continue to ride.

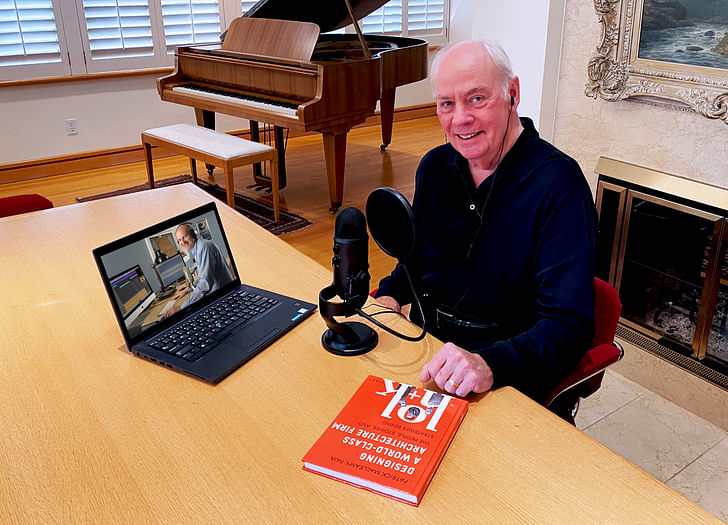

Eight decades later, MacLeamy believes the industry has much to learn from the approach taken by Hellmuth, along with his co-founders Gyo Obata and George Kassabaum. “Architecture is a passion, not just a profession, and my own passion for the field extends to the business side,” MacLeamy writes in the book, which ultimately spawned his podcast Build Smart. “Just as designers delight in finding elegant solutions to design challenges, I came to love finding elegant solutions to business challenges.”

In September 2024, I spoke with MacLeamy as the U.S. architecture industry once again found itself in turbulent economic conditions. What emerged from our conversation was a series of tips, both short-term and long-term, that MacLeamy believes architecture firms of all shapes and sizes can incorporate into their business strategies to improve their resilience in the face of economic downturns. The insights, including MacLeamy’s reflections, are set out below.

When a downturn hits and projects are paused, MacLeamy’s first piece of advice is to hang onto your clients. Sometimes, this can mean suggesting to a client that work continues on the project until the next milestone is hit, whether that be in the coming weeks or months. Beyond this, however, MacLeamy stresses the importance of maintaining communication with the client even after work has come to a halt.

“By staying in touch with the client, I don’t mean the occasional phone call,” MacLeamy told me. “Once a week, make an excuse to reach out to the client, whether an email invitation to have a coffee or to go to a local restaurant.” In addition to reinforcing your relationships for when economic activity picks up again, such conversations may lead you to offer services beyond the core architect function.

“Maybe they need some advanced planning on a project that is five years out,” MacLeamy added. “You will only know if you ask them and talk to them. Hanging onto the client is key.”

Clients are not the only people who require attention during an economic downturn. If you are a director or manager, your staff will likely be aware of any economic downturn and will begin to worry about its impact on them and their families.

“Communicate every day,” MacLeamy told me. “Get everybody in the office together and have a simple talk. Tell them where the firm is, what the status of projects are, and what your plan is to navigate the downturn.”

For MacLeamy, making redundancies should be a last resort. If the firm’s financial situation calls for a reduction in staff costs, MacLeamy recommends keeping the employee headcount stable, and temporarily reducing salaries. In this situation, MacLeamy recommends starting with your own salary before reducing those of your staff, and promising that the cuts will be accounted for and corrected when the firm’s finances are healthier.

“You have spent time and energy training your staff and blending them into your organization,” MacLeamy told me when asked why reducing salaries is a wiser choice than reducing employee headcount. “You don’t want to throw that away. You’ll end up back at square one again.”

If the bill goes out to the client but hasn’t been collected in 30 days, absolutely reach out to the client. — Patrick MacLeamy

MacLeamy’s final short-term tactic for surviving economic downturns appears obvious: “Manage your cash.” Yet, in MacLeamy’s decades-long experience, architects struggle to manage cash flows despite their importance in sustaining a business.

“We are tied to our clients, and we let our clients delay before paying us,” MacLeamy explained. “As architects, we often end up financing our client’s business because they are living off the money that they have effectively borrowed from us by not paying on time.”

In our conversation, MacLeamy emphasized the importance of having and adhering to a cash flow management program, regardless of the firm’s size. In larger firms such as HOK, MacLeamy suggests a 30-day window for billing projects after the architect’s work has been delivered. For smaller firms, with fewer clients to bill, MacLeamy suggests this be shortened to a week.

“If the bill goes out to the client but hasn’t been collected in 30 days, absolutely reach out to the client,” MacLeamy advises. “It is a good excuse to stay in touch. Ask if everything is alright with the bill, if it was received, and when payment is expected. You can be kind but firm.” If a client has not paid after 60 days, MacLeamy further advises architects to not count that money as “earned” and to not make financial decisions assuming that money is in their pocket.

In addition to managing cash ‘in,’ MacLeamy stresses the importance of managing cash ‘out.’ As our second tip highlights, reducing spending on employees should be a last resort. Instead, MacLeamy suggests seeking to temporarily defer payments on vendors or, if the firm is on good terms with its landlord, asking to defer lease payments.

“It’s not good practice,” MacLeamy warns. “But it is far better to have cash available to sustain the firm for 30, 60, or 90 days.”

While offering three immediate tactics for short-term survival, MacLeamy stresses that a firm’s resilience in the face of an economic downturn is decided primarily on the long-term strategies and contingencies in place before the downturn begins. Chief among these is to build a cash reserve. For MacLeamy, the importance of a cash reserve stems from personal experience, having used his first six months as HOK’s CEO to build a cash reserve in the firm at a time when its line of credit was under pressure.

“We ended up setting goals,” MacLeamy recalls. “How much cash do we need for the next recession? We decided that the first goal was 90 days of reserves, which can last you through small downturns. But it won’t get you through the big ones. Later, we extended our reserves to six months. Much later, we realized that with a strong cushion in place, we could also save money to be used for opportunities, such as upgrading software or paying a signing bonus to a talented young designer being tempted by another firm.”

In our conversation, I asked MacLeamy whether it was advisable to keep such reserves as ‘cash in the bank,’ or to invest the reserves in assets until they are needed. MacLeamy was clear: Cash is king.

“You might need the money tomorrow,” MacLeamy explained. “If it is in the bank, you can get it tomorrow. If it is invested through a broker, or in bonds, or in an office building, it will take time to access it. As large as HOK became around the world, we never owned an office building. It didn’t make sense to us. The cash is tied up in real estate, and you might not be able to access it for six months.”

Similar to cash management, MacLeamy sees people management as a key strategy for resilience in the long term as well as the short term. In MacLeamy’s experience, staff who are treated well by a firm will become selling points for your next project, or for attracting your next client.

“You should want to keep them happy,” MacLeamy explains. “In return, they will have a loyalty to you and your team. Pay them well, give them promotions, and make them feel appreciated. Perhaps they will become your next partner or your successor someday. Either way, treat them well; people are everything in a practice.”

The five final pieces of advice in this list stem around ‘diversification;’ a factor that MacLeamy places alongside cash management as a core consideration for building a recession-proof firm. MacLeamy advises firms to diversify their business to the maximum extent possible and to see every client and opportunity as an opportunity to diversify.

“If you learn how to design schools, churches, community projects, housing, hospitals, and so on, you will find that boom and bust cycles within those markets are different to one another,” MacLeamy told me. “Even during recessions, airports seem to always be expanding, whereas schools may go up and down. Diversify your business. If you put all your eggs in one basket, and something happens to that basket, you are done.”

If you put all your eggs in one basket, and something happens to that basket, you are done. — Patrick MacLeamy

In addition to diversifying its portfolio of typologies, MacLeamy recommends that a firm diversify the range of services offered within those building types. HOK itself is a working example of this approach in action, offering services across architecture, landscape architecture, lighting design, experience design, interiors, planning and urbanism, space management, sustainable design, engineering, and consulting. That said, MacLeamy sees an opportunity in firms of any size to expand their scope of services.

“I’m an architect, and I know how to design buildings,” MacLeamy explains. “But I could probably provide good interior design services, too, as well as programming and planning to bridge gaps when design services are down. This also helps me stay in touch with a client by helping with long-term planning for the next step in expanding their portfolio, campus, and so on.”

In our recent Archinect Business Survey, we asked architecture firms what steps they were taking to improve their own preparedness for downturns. One of the emerging themes from our community responses was the resilience of government contracts over private commissions. In my conversation with MacLeamy, I asked if diversifying by client type might also serve a firm well during future downturns.

“If they can, governments tend to spend money when the economy is slow,” MacLeamy explained. “If there is a slowdown, a public rail system, airport, or school tends to still have money available. In other words, your government is collecting taxes and working for your benefit all the time, not just when the economy is good. The private sector, on the other hand, has a greater tendency to pause until conditions improve. If you can diversify by client type, therefore, that is another great way of building resilience.”

MacLeamy’s final avenue for diversifying is geography. Today, HOK operates 17 offices across the United States, spanning all geographic regions. As MacLeamy explains in our conversation, a slow economy in one part of the country can be mitigated if staff in that region are redirected to support colleagues in more active regions.

In addition to its 17 domestic offices, HOK operates nine international offices encompassing Canada, Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and India, meaning resources can be diverted to more active markets not just in the United States but further afield. MacLeamy’s emphasis on the value of geographic diversity aligns with similar advice given to us by architects in our business survey, who cited international work as a reason for their confidence in surviving a downturn.

For more tips on how to expand your firm internationally, you can review our recent article on the topic, in which we spoke with Safdie Architects, Steven Holl Architects, and Mecanoo for insights on how their own practices secure and deliver services beyond their base country.

As our conversation drew to a close, I asked MacLeamy one final question, which many practice owners are likely to have asked themselves when thinking about their long-term future: When a downturn hits, is there an advantage to being a small firm or a large firm?

I put two trains of thought to MacLeamy. On the one hand, perhaps a large firm holds the advantage due to its increased reach, resources, and ability to bid for work, both large and small. On the other hand, perhaps a smaller firm can more quickly adapt and pivot in response to sudden economic shifts, with less bureaucracy and fewer overheads. Perhaps it's a toss-up between the two?

“It’s not a toss-up,” MacLeamy responded. “Big firms have a certain advantage because of the depth of talent and experience that comes from having a large practice. Yes, there is an advantage to being nimble, but it's really a question of leadership. In my opinion, small firms are struggling all the time. Even when times are good, they struggle with cash flow.”

Any small firm can be good; it all comes down to leadership. — Patrick MacLeamy

“Yes, if you are well organized, you can lead a small, nimble firm, and have a fantastic career,” MacLeamy added. “But in my experience, small successful firms tend to grow and learn how to manage growth. Every firm starts small. HOK started with three people, and now there are roughly 2,000 employees.”

“Any small firm can be good; it all comes down to leadership. If the leaders would just take the clear answers we have discussed today and take them seriously, every small firm could find much more success. I think architecture would be a lot more fun for every practitioner if that were done.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.