With the dramatic rise of homelessness in Los Angeles, addressing the issue has become a paramount concern. Political pressure is rising, and the onset of public programs, task forces, and initiatives have shown promise, but still face mounting roadblocks. In response, many are pounding their fists in frustration. This endemic has been in discussion amongst architects also, who, as citizens themselves, seek to contribute to a resolution.

The need for shelter is a basic human need, and the architect recognizes a duty to facilitate that need. But, when it comes to addressing an issue so marred with bureaucratic constraints, we realize something so seemingly simple is multifaceted and complex. As architects, how can we better understand those complexities? And what is our role in the manner? There isn't a single answer. But, let's look at the work of a few architects and investigate how each embraces their duty to listen and collaborate in order to help establish fruitful partnerships. Perhaps, our exploration might inform us as to how we can think more critically about this social dilemma.

The problem of homelessness contains many moving parts, and within this multidimensional landscape, healthcare service remains one of the larger obstacles to address. Living on the street is dangerous, and the risk of sickness and disease lurks daily. When a homeless person needs medical attention, more often than not, the only option is the emergency room. Here, individuals receive some attention and care but are then released prematurely as the demand for beds in our E.R.s cannot meet the need experienced by people who are homeless. Toiling on the streets, without the appropriate time to recover, these individuals are forced back to the emergency room. And the cycle repeats on and on until the inevitable takes place.

"Most of us have the opportunity to recuperate from illness at home or in a longer stay in a medical facility," writes Michael Pinto, AIA, and Michael R. O'Malley, AIA, LEED AP, both principals at NAC Architecture. "Without that opportunity, homeless individuals are not recovering from the conditions that triggered their first hospital visit. As a result, they become frequent visitors to emergency departments. It's not effective; it's not efficient; it's not humane." The pair call for the implementation of recuperative care facilities "that provide both acute and post-acute medical respite for homeless persons who cannot successfully recover from illness or injury in the streets, but who are not ill enough to remain in a hospital." An offering of this kind would give the homeless individual the environmental quality they need to fully realize their recovery.

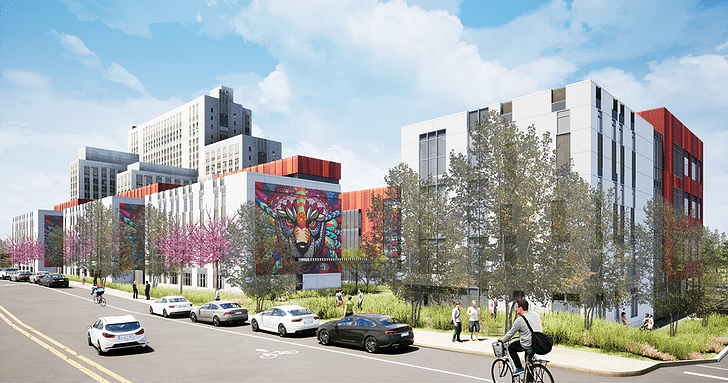

Such an implementation is already underway in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles County USC Medical Center is working to develop what they're calling the Restorative Care Village, a facility that will offer a robust range of services for people experiencing homelessness. Some of the components in this facility would include recuperative care, a sobriety center, a psychiatric emergency room, psychiatric urgent care, crisis residential housing, permanent supportive housing, and a wellness center. While the final inclusion of all of these elements is not certain, the development of the Restorative Care Village has begun. A first of its kind, this development will mark a national turning point in how we can address homelessness in our cities.

“The practice of architecture not only requires participation in the profession but it also requires civic engagement.”

- Samuel Mockbee, Architect

When Michael Pinto, AIA, Design Principal at NAC Architecture LA, got invited to a County meeting a couple of years ago, he wasn't sure what he was walking into. "I walk into the meeting, and I see the leadership from across the County Health System," Michael told Archinect. He shared how the group was discussing an initial idea for the restorative villages, advocating for a no wrong door policy, and addressing the novelty of the concept. This would be a facility that would receive people wherever they were. So, if one needed recuperation, it could be provided without the E.R.; sobering care, no E.R.; psychiatric care; whatever it was, this solution would cover all areas.

"Finally, the meeting chair looks up, and he says, 'Hey, didn't we invite an architect to this?'" Michael said jokingly. "And my colleague just kind of looks over at me, sort of queueing me to speak up. And we all start talking about this in terms of architecture and how to facilitate it." After some back and forth, and taking the initial vision cast by the County and its partners, Michael and the team at NAC Architecture came back with the beginnings of a concept, which became the graphic collateral for a white paper drafted by the County and later evolved into the scoping documents for a design-build team. Fast forward to today, and the LAC+USC Medical Center Restorative Village has already approached its second phase, with NAC's concept at the helm.

The Restorative Care Village will include two connected hubs, the Acute Care Hub and the Wellness Hub, and will progress in three phases. Phase 1, already underway, includes the construction of the development's bridge housing, split into two parts: Recuperative Care, for those in recovering from living on the streets, and Crisis Residential Care, for those dealing with domestic abuse and other challenges; both are part of the Acute Care Hub. Phase 2, just starting, includes the demolition of three empty laboratory buildings, making way for the new Wellness Hub, which will house a Community Resource and Recreation Center, services to secure employment, Permanent Supportive Housing, a Recovery and Respite Center, and Psychiatric Urgent Care.

Finally, Phase 3 will return to the Acute Care Hub, starting with the demolition of the vacant Women and Children's hospital, followed by the construction of the new Psychiatric Hospital and Psychiatric Emergency Department. Working with an existing site and through collaboration with the County, health professionals, and the surrounding community, NAC's challenge was dynamic and nuanced. In January 2019, the County released an RFP for design-build proposals, which ultimately resulted in the selection of CannonDesign. CannonDesign plans to construct the development in a mostly modular fashion in collaboration with ModularDesign+.

During their time working on the project, the team at NAC was careful to slow down, listen, and learn about the issue they were tackling. It's an approach Michael encourages more designers to adopt, to take off the "hero hat" and approach these broader social issues at a human level. "As architects, we have to be careful that we don't get out of our lane. We have limited tools and awareness," he told Archinect. "But, that doesn't stop us from working with and scaffolding a conversation with people who know what's happening." Architects have essential skills to bring to the table, but it's in conjunction with those who are ultimately charged with addressing these kinds of public issues. It is a team effort — the architect is one part of a much larger whole.

The team at NAC was careful to slow down, listen, and learn about the issue they were tackling. It's something Michael encourages more designers to adopt, to take off the "hero hat" and approach these broader social issues at a human level.

"For architects who want to get involved in a social issue like homelessness, I think it'd be a good idea to choose a nonprofit working in homelessness," said Helena Jubany, FAIA, Managing Principal at NAC Architecture Los Angeles in a conversation with Archinect. "They've done all of the homework, and so you don't have to reinvent the wheel. Volunteering and learning from those who've been studying this issue, I think, is the best approach." Helena has been on the board of A Community of Friends (ACOF) for 16 years. ACOF is a nonprofit developer whose mission is to end homelessness by providing quality permanent supportive housing for people with a focus on those with mental illness. The organization holds an extensive portfolio of full-service properties and is committed to the management and tenant support required to operate them.

Helena began as a volunteer serving food to the homeless and later began to consider how she might make a more significant impact. "Architects are well-positioned to help in this area. After some volunteer work, I wanted to expand my reach, and so over time, I moved to the board of ACOF," she explained. Helena is the only architect on the board at ACOF and collaborates with other board members in other areas of expertise to realize the nonprofit's mission. As an architect, Helena provides guidance, insight, and advice as it relates to the strategy and vision of the organization as it pertains to the architectural aspects of developing properties. That could be anything from helping to set up best practices to serving as an advisor for the nonprofit’s Housing Director on design-related issues. She went further to express the importance of understanding that a board position is not crucial for all architects who want to get involved. "Everyone has a gift. Some may want to volunteer on the ground, and others may feel more effective in a strategic role," she said.

In March 2017, Los Angeles voters approved Measure H, a ¼ percent increase to the County's sales tax that will provide an estimated $355 million per year for ten years to fund homeless services, rental subsidies, and housing. According to L.A. County, the measure is designed to support strategies in six primary areas:

Prevent homelessness

Subsidize housing

Increase income

Provide case management and services

Create a coordinated system

Increase affordable/homeless housing

This came about a year after the approval of Proposition HHH, a $1.2 billion bond intended to triple L.A.'s annual construction of supportive housing and build about 10,000 units for homeless Angelenos. But, while the city and County work on executing the permanent supportive housing, those living on the streets still suffer. In response, Mayor Eric Garcetti has introduced a new plan called A Bridge Home "to give homeless Angelenos in every neighborhood a refuge...until they can be connected with a permanent home." It was launched in 2018 after Garcetti and the City Council declared an "emergency shelter crisis."

The first site in response to Garcetti's initiative was El Puente, located in El Pueblo, the historic birthplace of Los Angeles. Teaming up with Gensler, Mayor Garcetti and Councilmember Jose Huizar led the group in realizing their effort in providing a site to serve the existing homeless population in the area. El Puente offers intensive case management services "that are carefully tailored to help homeless Angelenos stabilize, begin rebuilding their lives, and move into permanent housing as quickly as possible." Since the launch of A Bridge Home, there are a total of 29 sites open or in development across the city.

In this mission to address homelessness, many roadblocks stand in the way. NIMBYism, in particular, remains a recurring point of pushback. NIMBY stands for Not in My Backyard and refers to the tendency of locals to block homelessness initiatives in their communities. "A big part of our work at ACOF is educating communities on what we are bringing to an area. When people hear about permanent supportive housing in their neighborhood, they immediately think of it as an encampment," explained Jubany. "Often, our buildings are some of the nicest in a community. It's important to understand that permanent supportive housing is an organized and structured environment. We are looking to heighten the design quality of a neighborhood."

Michael Pinto elaborated on this point, explaining the common use of the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to halt homelessness projects. "Much of the public is very humanitarian and want people to be housed, but they get concerned about their kids walking through tent villages, or any other number of anticipated outcomes," he said. Moreover, Carol Galante, faculty director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, and a former assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development under President BarackObama told The San Francisco Chronicle:

"It (CEQA) has been abused in this state for 30 years by people who use it when it has nothing to do with an environmental reason...NIMBY-ism is connected to the fact that for everyone who owns their little piece of the dream, there's no reason to want development next door to them...CEQA gives them a tool to effectuate their interest. It's a sense of entitlement that comes with an incentive because it makes their property worth more money."

As well-intentioned and capable as some may be to tackle homelessness, there are those geared and motivated to stand in opposition.

For organizations like ACOF, who sometimes face blockage of this kind, it's interesting to see the final product of their properties, beautifully designed housing developments that look nothing like the falsely expected "encampments" NIMBYists fight against. As well-intentioned and capable as some may be to tackle homelessness, there are those geared and motivated to stand in opposition. Even aside from NIMBYism, challenges in acquiring land to build housing remains a mounting obstacle. Add that to the backlash many communities express amid the introduction of developments in their communities coupled with the growing political pressure and public frustration, and you get a social grenade with the pin removed.

In a summary provided by the Los Angeles Almanac, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, in 2019, approximately 50,000 to 60,000 persons may be found homeless on any given night in Los Angeles County, more than 44,000 of them on the streets. Youth, from minors through age 24, make up 8,915 of the County's homeless population (8,072 in 2018).

9% are under age 18.

31% are female.

15% are in family units (often headed by a single mother}.

16% are physically disabled.

28% are chronically homeless.

15% of homeless population have substance abuse disorders.

25% of homeless population suffers from serious mental illness.

7% of homeless population were victims of domestic/intimate partner violence.

What the numbers don't communicate is the fact that we have housed more homeless people than ever, but housing affordability has arrived as the primary root cause of the rise in homelessness. The crisis, among many others, is one of affordable housing.

...housing affordability has arrived as the primary root cause of the rise in homelessness.

We've all likely heard it argued that architects shouldn't get involved in social issues, that we should focus on design and refrain from sticking our head where it doesn't belong. "When I was in undergrad, anytime someone brought up a project where they wanted to have an impact, you got your hand smacked. It was like, 'Hey, don't you remember the failures of modernism?' Pinto reminisced. "I have students who share their frustrations. They're getting their hands smacked also. I tell them that not only can we make a difference, but that we have an obligation to use what we're learning and think about how it interfaces with the larger needs of society."

It's reasonable to think that architects cannot impact a societal issue like homelessness. Not by themselves anyway. As both Helena and Michael advocate, tackling a broad social problem like this takes collaboration, it's about going in, becoming a student, and learning about the communities and the people who need help. It's about capitalizing on the years of dedication, research, and education that many organizations and individuals have undergone to address this crisis. And it ultimately becomes about stepping back and asking oneself, what can I contribute here? We aren't saviors with capes and a roll of drawings, here to save the day, but rather fellow citizens and human beings with an expertise that can profoundly aid in the mission to support our neighbors in attaining one of their most basic human needs.

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

2 Comments

One of major reasons both LA and SF have enormous homeless populations is that the climate allows people to live outside and not freeze to death. Many aren’t even from those respective cities, though plenty are. The fiscal burden of housing the nation’s homeless population shouldn’t fall upon a handful of cities though. It’s a nationwide problem directly tied to healthcare, or rather lack thereof. Housing quite literally is healthcare as was illustrated in the first few paragraphs of this essay. Creating a special facility for such activities symptomatic of the problem ignores the catalysts that resulted in the project’s need to begin with. Salt Lake City is perhaps the only place in the US that has been able to make a dent in homelessness. The wild concept is, gasp, give homeless people a home. No questions no requirements no curfews or watchmen or social services contracts or sobriety tests. Literally just give these people the single most important thing they need to function which is somewhere to exist in peace and watch them turn their lives around all on their own the vast majority of the time.

I like the NAC Architecture village concept as well as the DE Fullerton heights building, as they provide not just housing units but a sense of community that is missing in these projects. The CannonDesign project seems less so, like the type of mediocre housing people dislike in their neighborhood and that homeless people avoid.

Development advocates have dropped the ball by focusing on red herrings like historic preservation (not an issue in LA / SF) and demonizing those it was supposedly to be working with. Focusing on architecture first would have done so much good, but lobbyists preferred the windfall of acronym posturing, which ended in defeat. Maybe next time they will appoint design boards to replace zoning restrictions to approve and disapprove dense projects. Having non-political design boards could do much good sifting through the developer garbage vs. good design

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.