Writer Colin Marshall presents a case for seeing Tokyo, Japan and Los Angeles, California as sibling cities, two places that have much in common formally, visually, and materially while remaining distinct and uncategorizable all the same. The two megalopolises possess a deep similarity," according to Marshall: They sprawl in similar ways, are multi-nodal in similar ways, and present vexing formal and urban realities that run counter to some of the more traditionally urban cities located within their respective countries.

Los Angeles, Tokyo, or both?

On the very first morning of my life in Los Angeles, I went to Little Tokyo. With its Japanese bookstores, its undigested chunks of 1980s architecture, and its late-night East-Meets west diners, the neighborhood had done much to draw my attention to the southern Californian metropolis in the first place. Los Angeles, a banner at its airport once proclaimed, is “a World in Itself," and indeed, it held out to me not just the promise of the city, but of elements of the East Asian city as well. After a few years in Los Angeles I moved to Asia itself, from Koreatown to Korea, but even living on the other side of the Pacific I haven't stopped thinking about Los Angeles. Nor have I stopped chiseling away, albeit remotely, at the exhilaratingly hopeless task of figuring the city-that's-a-world-in-itself out.

When I first moved to Los Angeles I'd never set foot in Japan, but when I made my first visit back to Los Angeles, it brought the Japanese capital immediately and vividly to mind. Or rather, one particular Los Angeles vista did: the city as seen from the 70th floor of the InterContinental Hotel downtown.

Not that I make it to Los Angeles much these days; I've been seeing far less of Little Tokyo than I have of the original Tokyo. When I first moved to Los Angeles I'd never set foot in Japan, but when I made my first visit back to Los Angeles, it brought the Japanese capital immediately and vividly to mind. Or rather, one particular Los Angeles vista did: the city as seen from the 70th floor of the InterContinental Hotel downtown. My attempts to master Los Angeles while living there included seeing it laid out from every high-elevation viewpoint I could: the Griffith Observatory, the Getty Center, the Bonaventure Hotel. But I left town before the opening of the Wilshire Grand Center, now the tallest building in the city — at least technically, thanks to the thin spike on top — and the one whose 70th floor the InterContinental's panoramic "Sky Lobby" occupies.

This view, a clearer and more expansive one than I'd ever thought possible of Los Angeles, took me back to the observation deck of Tokyo Tower. Originally built in 1958 as a broadcasting antenna (with the dual function of signaling to the world Japan's rapid rise from wartime devastation), Tokyo Tower is downright venerable compared to the Wilshire Grand Center. But whatever the historical and architectural differences between the two structures — to say nothing of the cities that spread out below them — as vantage points they felt unexpectedly similar. The visit, my first to anywhere touristic in Tokyo after half a dozen trips there, simultaneously indulged my love of all things of the mid- to late Shōwa era (the reign of Emperor Hirohito, which lasted from 1926 to 1989) and my desire to grasp the structure of Tokyo. But it also made me realize that, by comparison to all the cities one could try to understand, Tokyo and Los Angeles aren't entirely different endeavors.

Proposing a deep similarity between Tokyo and Los Angeles may sound absurd, but it isn't without precedent. Roland Barthes writes of the "quadrangular, reticulated cities" that are "said to produce a profound uneasiness: they offend our synesthetic sentiment of the City, which requires that any urban space have a center to go to, to return from, a complete site to dream of and in relation to which to advance or retreat; in a word, to invent oneself." He names Los Angeles as an example of such a center-less city, but he does so in an examination of Tokyo: Empire of Signs (here translated by Richard Howard), the book he wrote based on his travels to Japan in the mid-1960s. Back then Tokyo Tower loomed much higher than it does now over all the the other buildings around it, and it would have offered many visitors their first view, at two miles' distance, of the Imperial Palace, that empty (or at least silent) city center to which Barthes alludes.

For better or for worse, Los Angeles does not have an Imperial Palace. The argument that it also lacks a center of any kind feels plausible — so plausible that saying so was already well on its way to the realm of cliché by the time Barthes did it. "It is interesting, if not useful, to consider where one would go in Los Angeles to have an effective revolution of the Latin American sort," writes architect and Los Angeles enthusiast Charles Moore in his 1965 essay You Have to Pay for the Public Life. "Presumably, that place would be the heart of the city. If one took over some public square, some urban open space in Los Angeles, who would know?" The only hope, Moore decides, "would seem to be to take over the freeways, or to emplane for New York to organize sedition on Madison Avenue; word would quickly enough get back."

Unless one counts the modernizing Meiji Restoration of the 1860s, Tokyo has done without anything we would now recognize as an organized revolution. So has Los Angeles, a city which, like Tokyo, labors under the dual reputations of changing constantly, even excessively, as well as of never really changing at all. The history of Tokyo stretches back to the third millennium BC, yet almost the entire city looks as if was built within the past 50 years. As for Los Angeles, cinema scholar Thom Andersen writes in an essay on Jim Jarmusch's Night on Earth that, "because it was first for so many years — it built the first freeway system, the first airport for jet airliners, the first mid-century modern baseball stadium, the first shoddy neoclassical cultural palaces — it is in many ways the oldest U.S. city." Not everyone accepts Los Angeles' increasingly serious bid for preeminence among American cities, but then, Kyoto has yet to fully accept its Meiji-Restoration loss of capital status to Tokyo.

Not everyone accepts Los Angeles' increasingly serious bid for preeminence among American cities, but then, Kyoto has yet to fully accept its Meiji-Restoration loss of capital status to Tokyo.

Kyoto tends to win over foreign tourists in Japan more than Tokyo, much like how San Francisco tends to win over foreign tourists in California more than Los Angeles. That must owe in part to size and in part to expectation: both Kyoto and San Francisco look more like one expects a city to look, and most of their tourist spots are gathered within relatively compact areas. Neither the urban vastness of Tokyo nor that of Los Angeles, by contrast, contains much of widely agreed-upon sightseeing value. Just getting the lay of the land by going to the Bonaventure Hotel, the Griffith Observatory, and the Getty Center could well turn into a day-long ordeal. But to contrarian urbanists the difficulty of a city like Los Angeles can become an aspect of its appeal, and after just a few months of living there I prided myself on how well I knew my way around. Then, emerging one weeknight from a downtown bar, I encountered a bewildered-looking family of unplaceable European origin. "Can you tell us where is the commercial center?" asked one member. I stammered before gesturing vaguely in the direction of Grand Central Market, despite knowing full well it had closed hours before.

As far as downtown Los Angeles has come since then, "commercial center" would still be an unsuitable label for any part of it — or indeed of the greater Los Angeles area. The question of where to find such a place wouldn't make much more sense in Tokyo, which offers a plethora of "commercial centers" all over its map: Shibuya, Ikebukuro, Shinjuku, Ginza, Roppongi, and Naka-Meguro, to name just a few. Not coincidentally, those are also names of major subway stations. "In this enormous city, really an urban territory, the name of each district is distinct, known," writes Barthes. "If the neighborhood is quite limited, dense, contained, terminated beneath its name, it is because it has a center, but this center is spiritually empty: usually it is a station." Empty-centered neighborhoods in an empty-centered city: a neat formulation, but each station is also "a vast organism which houses the big trains, the urban trains, the subway, a department store, and a whole underground commerce," and it "gives the district this landmark which, according to certain urbanists, permits the city to signify, to be read."

both Kyoto and San Francisco look more like one expects a city to look, and most of their tourist spots are gathered within relatively compact areas. Neither the urban vastness of Tokyo nor that of Los Angeles, by contrast, contains much of widely agreed-upon sightseeing value.

Many have bemoaned the supposed unreadability of Los Angeles — in his travelogue American Vertigo, Bernard-Henri Lévy calls it "the prototype of a city with a poorly developed language, the prototype of unintelligible, illegible discourse" — and the absence of bustling transit hubs of the kind found in Tokyo surely has something to do with it. Los Angeles does have urban rail stations, and more of them appear every few years, though none yet resemble the vast organisms described by Barthes. (The transit system certainly has a long way to go before it will have to employ white-gloved station attendants to physically stuff commuters into rush-hour trains.) Some aboveground commerce does go on at Union Station on the edge of downtown, but the architect Thom Mayne has publicly complained about the impossibility of getting a meal there after 10:00 at night. To his mind this goes some way to disqualifying Los Angeles as a proper city, and it would take a vigorous partisan indeed to deny his point.

But then, vigorous Los Angeles partisanship has made something of a tradition of preemptively foregoing its claim to cityhood. Some of Los Angeles' champions have argued for considering it not a city but a "mega-region," say, or a "constellation of villages." Nobody would claim that Tokyo fails to qualify as a city, but many have described it in terms similar to these. Some even go so far as to call it "polycentric," a near-nonsense word still routinely used to exaggerate the strengths and downplay the weaknesses of Los Angeles' urban structure. Even in recent years, treating any one of the city's "centers" as a genuine center — a point of reference from which to see all other areas in relation — has had the potential to cause offense. (Writing a series of essays about Los Angeles and its neighborhoods while living there, I was mildly reprimanded by my editor for my tendency toward "downtown-centric" terminology.)

Western interest in Tokyo took off in the 1970s, by which time the Japanese economy had turned the city, firebombed to ruin not so long before, into what looked like an impossibly functional, even futuristic megalopolis.

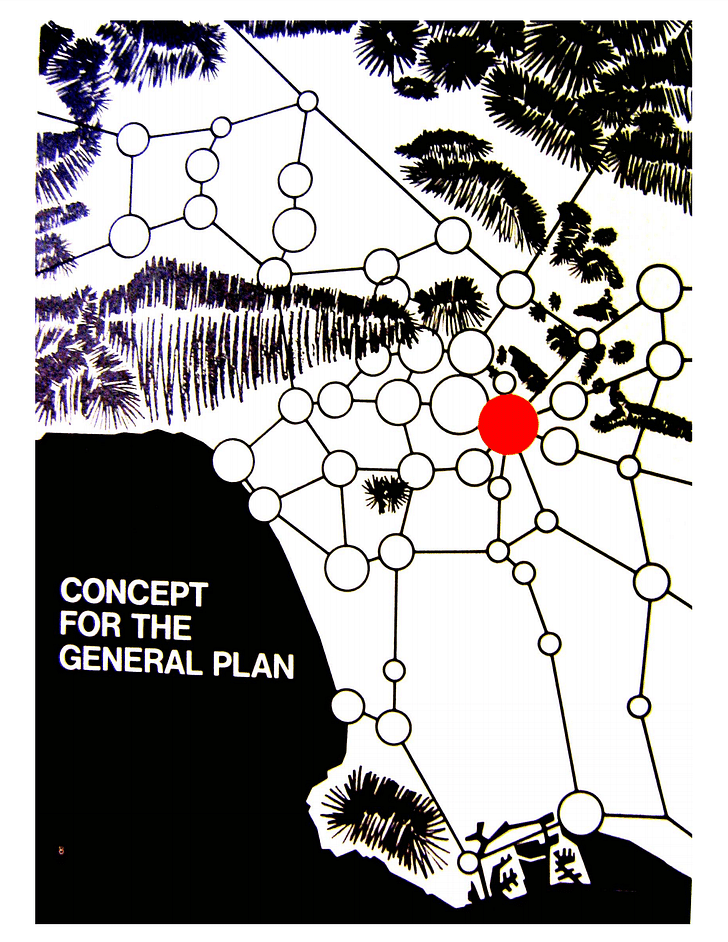

Western interest in Tokyo took off in the 1970s, by which time the Japanese economy had turned the city, firebombed to ruin not so long before, into what looked like an impossibly functional, even futuristic megalopolis. In that same era, the notion of multiple centers made it into the official language of Los Angeles' planning department. Put forth by City Planning Director Calvin Hamilton, the "Concept Los Angeles" plan proposed intensive development in 48 "centers" located all over greater Los Angeles. "Each center will have a 'core,' which will be the focus of activity," says the official document, which goes on to sound nearly Barthesian: "The core will contain the rapid transit station, high-rise office structures, department stores, hotels, theaters, restaurants and government offices. It will be designed to function on a three dimensional basis, with extensive use of air rights to permit development over streets."

The vision of Concept Los Angeles may not have been realized, but its language of dimensions has become more resonant with time. It certainly resonated in my mind as I gazed down from the InterContinental's Sky Lobby, remembering what I saw from Tokyo Tower. The experience of a city is rich to the extent that city makes use of all the dimensions. In most respectable urban cores you'll find different things depending on whether you walk to the north, south, east or west, but the better ones offer a similar variety when you move up or down as well. Many of the buildings of Tokyo are, practically speaking, vertical streets: ascend a single staircase and you'll pass a convenience store, a ramen shop, a jazz bar, an architecture firm, a real-estate office, a capsule hotel, and a bluegrass club — in that order. Such a building often also includes private housing, a necessity noted even by the drafters of Concept Los Angeles.

"The major emphasis in the core will be on business activities; however, the core will usually include housing, which in some cases will occupy the upper floors of multiple-function structures," says the Concept Los Angeles general plan. "Rooftops will be developed as landscaped plazas and open spaces for both public and private use. Schools, churches, government offices and public facilities can be located on upper levels, using landscaped rooftops as their grounds." It is just such use of the vertical dimension one sees from not the Sky Lobby of the InterContinental Hotel but the observation deck of Tokyo Tower, as well as what Concept Los Angeles calls "high intensity housing." In a core, the document envisions, "most residential structures will be 'medium rise' with a height of four to eight stories or 'high rise,' with a height of nine stories or more," all of which might as well be a description of the actual housing of Tokyo.

Many a Westerner who comes to Seoul, where I now live, regards with a kind of astonished revulsion the defining form of housing here: complexes of ten, twenty, thirty gray or beige towers, each of which rises to twenty, thirty, forty stories and bears a three-digit number to ease identification. Not every Seoulite lives in such a complex — I've certainly avoided it — but seen from the height of Seoul Tower their sheer prevalence makes them look like naturally occurring geological formations, of perhaps an invasive species. In Los Angeles nothing is less likely than the adoption of the Korean-style apartment complex, but the time of the Tokyo-style medium-rise building, by far the dominant form of housing in every major Japanese city, has clearly come. If every low-rise building seen in such abundance from the InterContinental were to be replaced by the kind of medium-rise building seen in such abundance from Tokyo Tower, nobody in Los Angeles would be talking about a "housing crisis."

If every low-rise building seen in such abundance from the InterContinental were to be replaced by the kind of medium-rise building seen in such abundance from Tokyo Tower, nobody in Los Angeles would be talking about a "housing crisis."

Such a replacement is, of course, easier written about than done, to say nothing of the completion of a Tokyo-grade rapid-transit network. Among the most basic of obstacles is the enshrinement in Los Angeles law of low-rise, low-density building, in large part an artifact of the preferences of the city's many 20th-century arrivals from small-town America. But Los Angeles, which first boomed as one big real-estate opportunity, has entertained the contradictory dream of becoming a city of houses — detached, single-family houses — even longer than that. Of Tokyo, American observer of Japan Donald Richie writes that "there is indeed little civic convenience of the architectural sort taken for granted in the West. Given the size of Tokyo, there are few large central parks and no real congregation of cultural facilities." Los Angeles has been both celebrated and condemned as a uniquely privacy-oriented, inward-looking major city, but it shares that quality with Tokyo.

In the Japanese capital, Richie writes, "an overall plan, a civic ordering of the city, is missing. There is no imposed and consequently logical pattern. Tokyo seems the least designed of capitals, not so much contrived as naturally grown. The West has only one city cultivated in this fashion, and that is Los Angeles." Throughout its comparative short history Los Angeles has hardly wanted for city plans, but like Tokyo it remains in the popular imagination a spontaneous, organic, disordered, and ahistorical urban environment. Richie quotes Los Angeles art critic Hunter Drohojowska-Philp: "To know Los Angeles you must know Tokyo as well. Tokyo and Los Angeles are both mirror cities, both wholly artificial, heavily reliant on surface appearances and essentially comfortable with life not as it was, but as it is."

Los Angeles art critic Hunter Drohojowska-Philp: "To know Los Angeles you must know Tokyo as well. Tokyo and Los Angeles are both mirror cities, both wholly artificial, heavily reliant on surface appearances and essentially comfortable with life not as it was, but as it is."

Having been created for the current era alone contributes excitement to the built environment of Tokyo, just as it once did to the built environment of Los Angeles. Over countless generations, earthquakes and fires made Tokyo accustomed to continuous rebuilding; relatively cheap land and a paucity of acknowledged historical context gave rise in Los Angeles to a culture of architecture as striking and dynamic as it was disposable. The disposability has gone, but so has the strikingness and dynamism: what manages to get built now, up to and including the dull Wilshire Grand Center, has none of the architectural daring, bravado or folly for which those who never go to Los Angeles assume the city is still known. Even the aesthetic swashbuckling of the "L.A. School" architects of the 1970s and 80s feels as if it has slipped out of living memory, despite the fact that its leading lights — Thom Mayne, Eric Owen Moss, Frank Gehry — are all alive today.

But then, Tokyo could also take a lesson from its own recent past, and from one of its most impressive 20th-century architectural minds: Kurokawa Kisho, co-founder of the Metabolist movement that cast the built environment of the city in biological terms. Kisho and his collaborators (a group including Kiyonori Kikutake and Fumihiko Maki) advocated an urban “metabolic cycle,” he writes in his book Metabolism in Architecture, that “divides architectural and urban spaces into levels extending from the major to the subordinate and which makes it easy for human beings to control their own environments.” In practice this meant using “industrialization and prefabrication to mass-produce spaces at low cost,” but also to “restore to architectural spaces something of the characteristics and feelings of the individual human being — characteristics and feelings that are lost when architecture is made anonymous and impersonal.”

Well before visiting Tokyo Tower I made my pilgrimage to Kurokawa's best-known building, which is also Metabolism's best-known building: the 1972 Nakagin Capsule Tower, a complex of cubic living environments, all designed for regular removal and replacement, attached to a central core. As Kurokawa wirites, the building “is not strictly an architectural expression of an apartment house, it is an expression of the 144 people who reside in its 144 units.” It also exemplifies the architect’s vision of spaces “composed on the basis of the theory of the metabolic cycle,” making it “possible to replace only those parts that had lost their usefulness and in this way to contribute to the conservation of resources by using buildings longer.” But in a betrayal of Kurokawa's vision, none of the capsules were ever removed, let alone replaced, and for decades the building has stood there slowly deteriorating on its prime piece of Ginza real estate. Meanwhile, advocates for the Nakagin Capsule Tower's demolition and advocates for its preservation have argued themselves into a standstill.

Many buildings in Tokyo date from the 1970s and even more from the economic-bubble 80s, a time when the land occupied by the Imperial Palace alone was valued higher than all the real estate in California combined. In those days Tokyo looked like the future to more or less everyone, not least because of the influence of Japanese money — which at that time paid for more than a few still-standing pieces of Los Angeles, in Little Tokyo and elsewhere — on built environments around the world. This trend of Japanification was projected into the future by science-fiction films like Blade Runner, set as it is in a Tokyo-hybridized Los Angeles of the year far-flung year 2019. "Blade Runner has been called the 'official nightmare' of Los Angeles, yet this dystopian vision is, in many ways, a city planner’s dream come true," says Thom Andersen in his essay-film Los Angeles Plays Itself. "Finally, a vibrant street life. A downtown crowded with night-time strollers. Neon beyond our wildest dreams."

"Blade Runner-ization" was once a standard term of condemnation used by Angelenos loath to see the city grow dense and vertical. Those particular Angelenos have lately lost much of their influence, but to what extent Los Angeles can realize its considerable potential by following the example of Tokyo — its fellow "limitless, indeterminate city par excellence," in Lévy's words — remains to be seen.

"Blade Runner-ization" was once a standard term of condemnation used by Angelenos loath to see the city grow dense and vertical. Those particular Angelenos have lately lost much of their influence, but to what extent Los Angeles can realize its considerable potential by following the example of Tokyo — its fellow "limitless, indeterminate city par excellence," in Lévy's words — remains to be seen. I plan on visiting Los Angeles every few years, and on every visit I intend to take in the city from the InterContinental Hotel's 70th floor. Not only do I hope the cityscape on view fills with taller, more varied buildings, expanding itself deeper into each dimension, I hope it changes dramatically each time, metabolically processing the currents of money, trend, and activity that pass through it. (The important dimensions of a city aren't just spatial but temporal as well.) Then I'll descend and walk to Little Tokyo, where an under-construction subway station will one day connect two trains lines spanning nearly the entire length and breadth of greater Los Angeles. If anywhere in Los Angeles a station can become the engine of a neighborhood — a Shibuya, an Ikebukuro, a Shinjuku — it will be there. Sometimes I wonder whether I could ever live in Tokyo. But I suspect, if all goes right, Little Tokyo may ultimately have more to offer me.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. He created the video series The City in Cinema and is now at work on a book, The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. He created the video series The City in Cinema and is now at work on a book, The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles.

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

1 Comment

There are many "cities" within the metropolitan Tokyo. Such as Shibuya, Shinjuku, Ikebukuro, Ueno...etc. Each "node" has its own characteristic, culture, and "center".

What LA needs might not be just a (commercial) "center" but a series of nodes in different neighborhoods.

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.