Architecture, like any field, is one filled with endless recordings, writings, images, and material of its long history. Books hold the information of the ages, yet so many of us are "too busy" to read any of it. We take our access to books for granted. But there are those of us who genuinely want to change that. We want to spend more time reading. We know that it's a practice that can help us grow and improve in our professional (and personal) pursuits. But, still, we have trouble making it happen. I think that sometimes, putting things into a certain perspective can help us make shifts like this in life. This article shares the early life of one of America's greatest citizens and how reading set him on a path to rid the world of one of its most horrifying institutions. Hopefully, a little snippet from his life can help give us an idea on how we might situate reading into our busy lives.

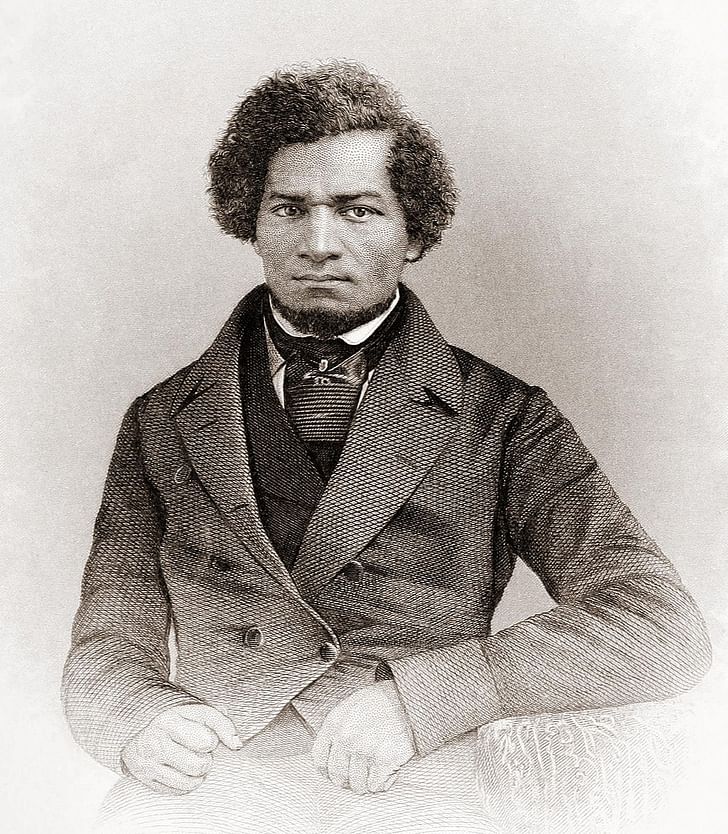

As a boy, Frederick Douglass lived enslaved on the Wye Plantation in Talbot County, Maryland. He was under the care of a ruthless overseer named Aaron Anthony. According to Douglas, it was a terrorizing childhood. But when he was nine years old, he caught a stroke of good fortune. Anthony was sick and getting older, and his estate would soon be taken over by someone new. As a result, the enslaved people in his possession had to be redistributed.

Instead of being shipped to another plantation, Douglass got lucky and was sent to Baltimore to live in the home of Hugh Auld. City life versus life on the plantation? It was a deal that Frederick could not believe. He had heard of Baltimore and, excited as any boy would be, counted down the days until his departure. We have to remember that the young enslaved boy had never seen a city before; he didn't even have an accurate concept of time. Life on a plantation kept enslaved people detached from the rest of the world. For Douglass, as he puts it, seeing Baltimore for the first time was like being a "traveler at the first site of Rome."

...seeing Baltimore for the first time was like being a "traveler at the first site of Rome"

After he arrived to the city, Frederick was taken to the home of his new masters, Hugh and Sophia Auld. During his first couple of years with the family, Sophia treated him much more like a son than her property, making him feel almost like a "half-brother" to her real son, Tommy. Aside from her sweet nature, the true gift Sophia gave Douglass was in teaching him to read. But after a few years, when Frederick was about eleven years old, Hugh, Sophia's husband, forbade her to continue teaching the young boy.

It was "unlawful" for a enslaved person to read in Maryland, he told his wife, and it would "forever unfit him for the duties of a slave." Hugh was right, and Frederick, overhearing this argument, began to envision a way to liberate himself. In his biography on the famous abolitionist, David Blight elaborates, "If 'knowledge unfits a child to be a slave,' Douglass later wrote, then he had found the motive power of his path out, or at least inward, to freedom."

Despite his new boundaries, Douglass still would sneak newspapers and books into the home, take them to his bed, and continue in his self-education. Quickly, this became a problem in the Auld house. Sophia was constantly policing the young Douglass' rebellious behavior, continuously catching him reading in some corner one of his smuggled books or newspapers.

Understanding that he needed to avoid Sophia's watch and determined to realize his literacy, Frederick, carrying his Webster's spelling book, headed for the streets. He made friends with some of the local white boys and would give them the bread Sophia had made for him each day as payment for spelling lessons. There was no stopping the young buck from reaching his goal.

If we fast forward through the life of Frederick Douglass, we find him sorrowfully returning to the Wye plantation where he faced daunting hardship, a failed escape, and relentless punishment. However, luck finds him once more, and he returns to Baltimore. After a while, Douglass the enslaved man, becomes Douglass the orator, writer, and most famously, the abolitionist. He embarks on a dramatic escape from Baltimore to Philadelphia, then to New York, and eventually changes his name. (Douglass was born Frederick Bailey, he changed his name to Frederick Douglass to avoid recapture after he escaped. In this article I use "Douglass" throughout to minimize confusion). Newly married and ready to embrace his life's task to abolish slavery, Douglass turned to his most potent asset, his voice.

It's in his masterful use of words and countless speaking tours, traveling throughout the United States and eventually to Europe, that Douglass is able to make his most profound impact. He later founded a newspaper, The North Star, writing to thousands of readers, and published three autobiographies of his life. The once curious enslaved boy was now a formidable reformer, who would stop at nothing to rid the world of the injustice of slavery.

That initial determination to learn to read, and eventually, to write, gave Douglass the tools to challenge angry mobs, racist States, and even Presidents. Reading became his fuel, and words became his weapons.

For Douglass, reading provided him with a path to freedom. He needed to read. For us, life is not as grim, but what reading does give us, I think, is just as powerful. When we open ourselves up to the ideas of other people, humble ourselves enough to learn from them, we can begin to see the world in new ways. In a profession like ours, so dependent on consistent creativity, this becomes an invaluable practice.

I remember when I read Mastery by Robert Greene. After I graduated from college, I was so eager to be "great," to accomplish a ton of things, get licensed, have my own firm. The list was endless. I wasn't content with where I was. I was impatient. Mastery helped me to understand the value in the process of learning something. One of my favorite quotes from the book is: when it comes to mastering a skill, time is the magic ingredient. After I read it, I found a new joy in being a student, in submitting myself under someone and enjoying the process of learning.

I grew up reading. My mother made sure of that. On average, I read about one new book every week, depending on length. I've done this on and off for years now. And even though all of those books impacted me in some way, there was something about this one that just hit me. Perhaps it was a combination of my age, circumstances, and outlook. Can you guys relate? Was there a book that changed how you looked at things?

I think we do ourselves an injustice by not reading. There are thousands of years of recorded knowledge and history just sitting out there waiting for us to access. How could we not take advantage of that?!

Without fail, every person who has impacted me on some level, be it from their mentorship, leadership, or instruction, has been a diligent reader (with the exception being those people with unique life experiences). I can't think of something more unattractive than someone who is close-minded. To quote Einstein: the measure of intelligence is the ability to change. He's totally right.

The leaders that I've admired in my past jobs have always been those who were comfortable being wrong, or changing their minds, even after they advocated for something that didn't work. They were open-minded. On the contrary, working under people who "were always right" and never considered any other ideas but their own, was a complete drag. I couldn't get away from them fast enough. A willingness to be open-minded coupled with an eagerness to learn always produces a dynamic professional.

Like anything, we prioritize what's important to us. I think reading is important work. It's not in the same boat as watching TV or something we do for leisure. Douglass wasn't looking to entertain himself. Instead, he was working to empower himself. How many breakthroughs have there been because someone was eager to learn, to read those who came before them? Countless.

What are you reading? How has it impacted you? Changed your worldview?

It's the people I've met in architecture who are some of the most well-read individuals. We've talked about the wide-ranging interests of our profession in past pieces. This intrinsic nature lends itself to the prolific researcher. So, in the end, I'd leave you with a question. A serious one, share your answers in the comments or email me. What are you reading? How has it impacted you? Changed your worldview? In a profession so tied to the well being of the public, let's embrace this amazing opportunity we've been given and tap into the endless knowledge we have right at our fingertips.

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

4 Comments

Sean: this is a great topic choice!

I'm a little embarrassed to admit the book that I will cite. It is Albert Speer's Inside the Third Reich. Speer was an architect who became Hitler's most trusted advisor during the latter half of World War 2. Several historians have postulated that Speer's organizational skills prolonged this war by a year and a half. I read Speer's book as a teenager long before I knew I wanted to become an architect. What impressed me then -and remains with me to this day- was Speer's ability to dispassionately see a situation from several points of view. It was this ability to rapidly adapt to changing circumstances that enabled him to continue Germany's war effort long after the Allies thought that they had obliterated Nazi Germany's supply lines and infrastructure. While in architecture school, the book came back into focus for me because we were continuously challenged to explore a wide range of possibilities in pursuit of a design solution. Although Speer was not a design inspiration per se, I learned to stop being self-conscious and look widely, working through the bad and the ugly in pursuit of the good.

Much more recently, I was surprised to read that one of the world's most inventive and engaging sports writers -Cathal Kelly- also cited Speer's autobiography as an important book. Although I'm at a loss to explain why this book influenced Kelly, he is peerless in his generation of fresh and breathtaking metaphors and analogies. He is as much fun to read as Bert Sugar. Like Sugar, I like to read Kelly's work aloud to family and friends. I'll bet that Kelly's success has something to do with his multi-valent perspective; before Kelly comes up with a perfect analogy, he likely has to try on and discard several stinkers. I know that I still do!

Thanks a lot for taking the time to leave a response!! I don’t think there is any reason to be embarrassed by the way! I find it fascinating how much we can learn even from those we despise. There was a talk that I heard a while back (I forgot who it was) but the person basically was saying that we should always focus on the accuracy of what a person is saying rather than decide to listen to them based off of if we like them or not. I think it’s the same with people like Speer, Mao, Stalin. Tons to learn from them but not on the top of my friends list ;). Thanks again!

thinly veiled...

Lest anyone think that I -or Sean- are in any way endorsing the work of history's monsters and their enablers, I'd like to add one additional observation. Towards the end of Albert Speer's life, he was extensively interviewed by Gita Sereny. Although a generation younger than Speer, Sereny came prepared with exhaustive archival and eye witness evidence. On a couple of subjects- concentration camps and the Nazi's use of forced labour, Speer could not deny that he did not have detailed knowledge of his regime's horrors when presented with evidence to the contrary.

My interest in Speer began with a desire to better understand the circumstances that brought my parents to the United States and Canada. In learning about Speer, I found one positive quality, a quality that is nurtured and valued in most design oriented schools. This method is, after all, an extension of and an improvement on the thesis- anti-thesis- synthesis method of design exploration. Clint Eastwood (The Good, The Bad and The Ugly) will get you to a position of design excellence more surely than Karl Marx.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.