In 2015, 30 students set out on a new part two course at the UK’s first full-fledged independent architecture school for more than a century. Run by former Architectural Review editor Will Hunter with architects including Nigel Coates, Clive Sall and Deborah Saunt, the London School of Architecture launched with high expectations.

As fees headed towards £9,000 per year at other London institutions, this one was aiming to keep the cost of architectural education down at a more affordable level and one which wouldn’t mean students comes out of university with almost £100,000 of debt and ill-equipped for life in practice.

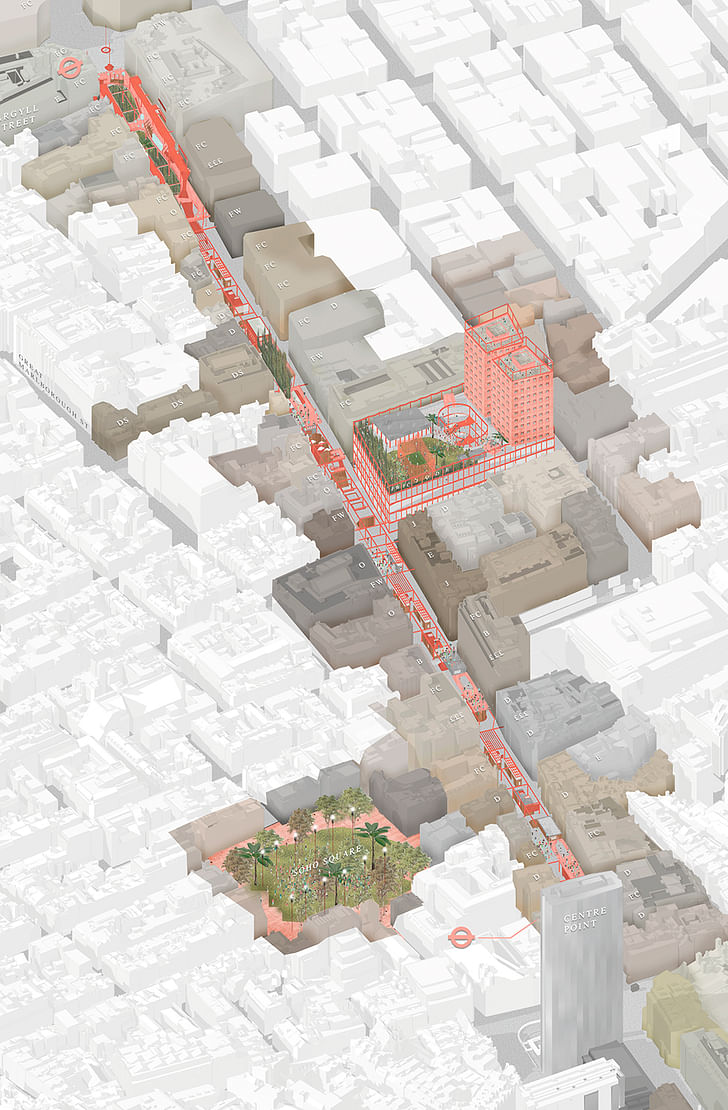

Now two years in, its first set of students have completed their studies. The work on the walls of its home in Somerset House display competency, inventiveness and a clear understanding of the issues which London is facing. Projects tackled issues including climate change, population growth, income inequality, and education and health disparities focusing on a London for tomorrow.

Laura Mark talks to school founder Will Hunter about the challenges of setting up a new architecture school.

Why did you decide to set up a new school of architecture?

We set up for two main reasons: we were aware that in 2011 when the fees went up to £9,000 per year architectural education became very expensive. We wanted to make a lower cost form of architecture. At the school, we wanted a different pedagogical model for teaching architecture that was much more engaged with the city, more collaborative, and related academia and practice. We wanted to look at how the world is changing and where architecture is going to be placed in that. We are the only discipline with spatial intelligence so we have a huge role to play in the world as we move forward.

At the school, we wanted a different pedagogical model for teaching architecture that was much more engaged with the city, more collaborative, and related academia and practice.

How have the first two years gone?

In our first year, we had 30 students who came to us when we had no building, no accreditation and no history. But now having done those two years, we have a home at Somerset House, we completed our ARB accreditation, and the RIBA has validated us with no conditions, so we are a much stronger enterprise now. There is a high level of enthusiasm by the people who have got involved and there is a real pioneering spirit from the first cohort which has been continued through the school.

We’ve been really impressed by how the students and the practices have collaborated together. There is a generosity and dialogue amongst people that is quite rare. There is a great energy and support from the wider practice network.

What have been the challenges in setting up a new school?

There were two main challenges. The first was raising money and startup funding. We’ve now raised around £400,000 from our founding patrons and practices. We’ve found support for what we are doing but it has been challenging.

The second challenge was dealing with the accreditation and getting through the processes while meeting the requirements. We are now applying for access to state finance for student funding and that is complicated. It is the same requirements that apply to a university and there is a lot of regulation to build that level of trust.

What makes this course different?

We have a very strong relationship with practice. We currently have about 55 practices in our network and they offer placements to our students in their first year. Students work three days a week. Partly that is the financial model – they are paid £12,000 which is the same as the fees so there is an equilibrium between tuition fees and earnings which we feel is important, but we also wanted students to be an active participant and an observer in the office. They write a manual on the practice which they are working in and they then write a manifesto for the office which they see themselves being in in ten year’s time.

We have a much greater focus on the city and we use it as a campus. We have a base in Somerset House but we do a lot of teaching in the offices of those network practices or in other spaces which we can borrow. For our projects we move to a different borough of London each year.

In first year, we have what we call a design thinktank project where students and practices collaborate together. They produce design research about a pressing architectural or urban issue. Then in second year we want the students to become better versions of themselves and not mini versions of their tutors so we have no unit system.

How do you manage to keep fees so low?

The main overhead we have reduced is in the buildings – we rent spaces as and when we need them and we borrow spaces from the practice network for odd bits of teaching. We are validated by London Metropolitan University, but we don’t have big centralised departments like large universities do. Our upper level management is relatively thin. We are governed by a board of trustees, but we focus most of the money on teaching.

The school has changed locations a few times over the past two years. How does it feel to now be settled and in one place?

We started at Second Home – the building designed by Selgas Cano – and it was really about being part of Tech City alongside entrepreneurs and artists. It really suited us in the first year. But the students really wanted a workshop so we settled on Somerset House’s Makerversity. It has woodworking, metalworking, rapid prototyping – everything we needed and we worked there until a studio in the building also became available. Somerset House’s agenda is to make a site of cultural production in central London so we fit much more with that. It was a great opportunity for the school – it’s on the Thames and a great axial point of London and you get to meet all these other great creative people who also work here.

London is a very complex metropolis with lots of complex issues, and it is on our doorstep. Instead of going off to places like Tokyo or Las Vegas – which is highly expensive – we can look at something in more depth here while keeping costs low.

Who teaches on the course and what agendas do they bring?

Tom Holbrook has stepped down so we are currently recruiting for a new head of urban studies. Deborah Saunt leads the design thinktank and is in charge of the first year. James Soane runs critical practice which covers the relationship between school and practice. Clive Sall is head of second year and Lewis Kinnear is head of tectonic studies. They all have careers in practice and non-teaching practice.

We then have six tutors teaching in second year from our practice network. We have a lot of people who are experienced in making cities and they bring an open-mindedness about how practice is changing but they also have a lot of experience in making architecture.

Will the school’s projects always be London-centred?

All of the design projects are based in London but the thinktank projects can be based anywhere. London is a very complex metropolis with lots of complex issues and it is on our doorstep. Instead of going off to places like Tokyo or Las Vegas – which is highly expensive – we can look at something in more depth here while keeping costs low.

As a new school how difficult is it to gain validation from the RIBA and ARB?

ARB accredits your course based on the paperwork that you produce before you open. They have procedures to ensure that what you say you are going to teach will meet the requirements of the EU directive. They are completely even-handed about what they are doing. It took some time but it was fair and we knew what the goalposts were and they didn’t move. It was predictable.

The RIBA comes to look at the work once you have finished and they came a couple of weeks ago. They look at the quality of the work and the whole institution. Their approach was that they were interested in what we were doing and they were enthusiastic about it.

Do you plan to keep the number of students low or is there pressure for you to grow?

Next year, we might have slightly more students. We have had 30 per year for the first two years and that might go up a little bit.

We have a lot of very good students apply to us from the UK and the rest of Europe. They see what we are doing as quite unique and there are not many others doing it. We get people who are looking for something different. It doesn’t appeal to everyone.

Have you aimed for the school to create a specialism in anything?

We want to be propositional rather than dystopian and are projective. We don’t want to be a school that just cares about how architecture looks (a more avant garde model) but we also don’t want to be just about how it works (the more polytechnic model). We don’t want to be just subjective or objective. We want to be able to tap into lots of different knowledge bases. We have a very open culture and are very entrepreneurial, constantly looking for new models.

Do you plan to make any changes?

We will fine tune some of the programme after having now run it through for a cohort but we won’t make any major changes. We are looking at what other courses we could offer.

See more of the students work here

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.