This week, we talk to Iman Fayyad. Iman holds a Master in Architecture with Distinction from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she was the recipient of the American Institute of Architects Certificate of Merit, Faculty Design Award, and the Araldo A. Cossutta Prize for Design Excellence.

Thesis Review is a collection of conversations, statements and inquiries into the current state of thesis in academia. Thesis projects give a glimpse into the current state of the academic arena while painting a picture for the future of practice.

What is the thesis?

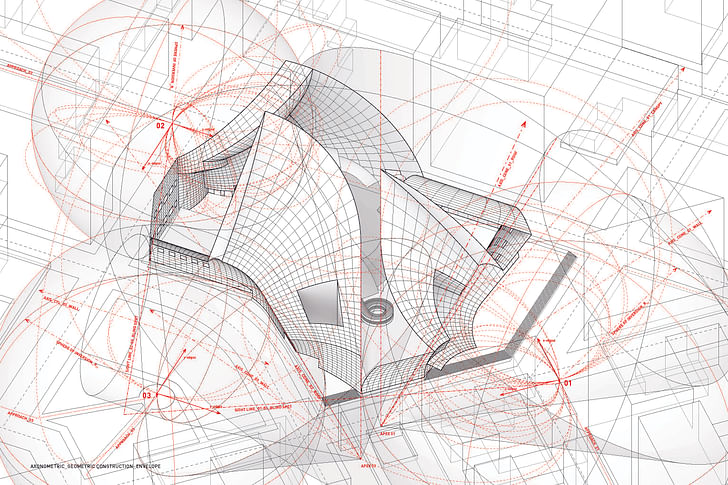

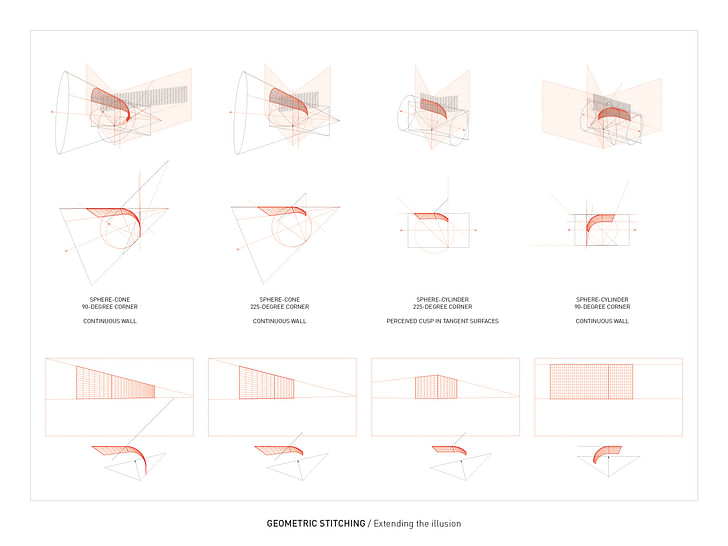

The thesis, entitled The Phantom Projective, is an investigation into the production of real and illusory form. It addresses the cognitive disconnect between objective reality and subjective perception as it relates to our experience of space. The research looks into a specific type of projective transformation— a technique developed by cartographers as a type of conformal map to flatten the globe onto a plane—and appropriates its use as a perspectival tool to map three-dimensional spherical space onto two-dimensional Cartesian space. The process produces an architectural object that has two simultaneous identities— one planar, rectilinear, Cartesian; the other spherical, radial, Polar. The identity that is experienced is contingent on the position and movement of the human subject in relation to the object.

The spatial effects of the technique are exhibited in the speculative proposal for a concert hall designed to calibrate the movement and experience of the user—their entry sequence from the street to their seat, and the dynamic transformation of the geometry of the space based on their position and direction of travel—ultimately redefining the relationship between the viewer and the viewed. The methodology affords an opportunity for the production of space that attempts to bridge the gap between what form needs to do (functionally, both architecturally and urbanistically) and how the human subject expects form to behave.

What was your inspiration for the thesis?

Much of the work and research I had done at school up until that point looked at how techniques of descriptive and analytical geometry have been deployed historically as well as in more contemporary design methodologies to generate form. With an interest in the development of orthography and perspective construction, I had studied anamorphosis and other techniques of visual distortion that became common practice in the Renaissance and the Baroque. These tropes were applied generally to make interior spaces appear larger than they actually were, obscuring the urbanistic constraints imposed on them. One of the more recognized examples is the distorted choir of Bramante’s Santa Maria presso San Satiro. Taking cues from the ways in which these trompe l’oeils successfully manipulated our visual experience, I was interested in thinking about how these techniques could go beyond the creation of a mere illusion.

On the other hand, my interest in geometry led me to consider the possibility of form existing in multiple geometric spaces of construction or coordinate systems. Of particular interest to me are forms that embody certain geometric properties that demand an understanding of their multiple states simultaneously. For instance, developable surfaces (singly-ruled surfaces that can unroll to flatness without distortion), by definition exist both in 2D and 3D simultaneously, and both states (the rolled and unrolled) can be used interchangeably to design three-dimensional space. A lot of this thinking dates back to the practice of stereotomy prior to the Renaissance and the invention of descriptive geometry that allowed architects to translate drawings of unconventional and complex three-dimensional geometries to stonemasons. This idea of the mapping of flatness to three-dimensions and the metrical equivalence of geometric form in various states served as a vehicle to address the relationship between visual distortion and three-dimensional space. The technique used specifically for this research derives from both descriptive and analytical modes of thought by using single point perspectival projection as a way to design an object that exists in two states—one ethereally on the picture plane, which changes based on the location of the subject in relation to the object; and the other, its true objective three-dimensional shape.

How did it change over the course of the process?

A big challenge with technique-based research is understanding the limitations of the process, in most cases explored initially in isolation. Things “work” because they operate in a vacuum. This is a necessary step in understanding the full potential of a rule-based system and gives you the opportunity to author interpretations of something so closed and absolute. However, one of the ongoing conversations for me was finding a tangible application of this technique and understanding its architectural implications and consequences in a way that looked beyond the historical and technical narrative. I went through many options for choice of program and scale—ranging from a city, to an urban plaza, to a courthouse, to a museum. The choice of theater to test these ideas was an appropriate balance—a civic center that would command a distinct urban identity, and a program that already comes with deep theoretical roots in spectatorship and the political power of the privileged point of view.

A big challenge with technique-based research is understanding the limitations of the process, in most cases explored initially in isolation.

How do you see this thesis progressing into your career?

I think ultimately what a student thesis represents is both an epilogue and a prologue. On the one hand, thesis is both the culmination of a body of work and modes of inquiry developed as a student for three or so years, as well as a springing point for an architect’s professional career moving forward. In my mind, a thesis is not the work produced in a student’s final semester in graduate school, but a product of every studio project, written paper, and seminar assignment that preceded it. That is not to say that whatever you do for thesis will also determine or inform everything you do as a practicing architect. But whatever the discoveries made during thesis should manifest themselves either visibly or otherwise in your thinking as a designer. For me, I would like to continue to think of ways in which human experience can inform spatial constructs, as well as consider more advanced technical applications of the system such as in VR technology.

What were the key moments within your thesis?

One of the most challenging aspects of a thesis that deals with movement and experience is its representation. Early on I realized that the most effective way to demonstrate what I was exploring was via physical model. Due to the nature of the investigation, however, the success of the technique was highly sensitive to both the scale and proximity of the human eye relative to the object. In terms of drawing, one of the only ways to truly represent the full identity of the geometry was not through traditional static images (renderings, perspectives, or orthographic drawing); but through animation. A single static perspective drawing represents the flattened picture plane onto which your eye projects the image of three-dimensional space. In reality, the picture plane is not static but rather successive and sequential. There were two revelatory moments for me during thesis— one was that the three-dimensional identity of the project was designed directly through the picture plane.

Designing the two coherent “identities” of the building required the literal designing of the picture plane (designing the subjective reality that was to be “perceived”) on one screen while modeling its alter-ego (objective three-dimensional reality) on the other. This back-and-forth, and getting the two worlds— the parallel and the perspectival— to speak to one another was a critical point for me personally. It required translating the indexical mode of thinking—to which I was more readily attuned—to the subjective and perceptual consequences of it. Animations were important because they demonstrate the “in-between” states of the object, which appears to liquify as the subject moves away from the point at which the shape “snaps” to the Cartesian grid. In addition to animations, the final representation consisted of pairings of orthographic drawings with perspective images— the orthographic there to depict and explain the reality of the perspective image.

How does your thesis fit in within the discipline?

I think the inquiry touches on two ongoing discussions in the discipline. One is the role and status of pictorial representation, and the other is the genesis and use of reductive architectural form. One of the issues this technique attempts to address, when applied architecturally, is the centuries-old preoccupation of the discourse with the gulf between parallel projection and central projection. Perspective has historically been considered to be an “untrue” representation of reality. Considering a technique whereby the untrue or imaginary identity of an object can exist hand-in-hand with an alternate identity (one that operates coherently objectively) frees us to blur the distinction between what is real and what is imaginary. In this case, the three-dimensional reality of an object is designed directly from a particular desired image of its “untrue” or imaginary identity—the perspectival distortion of the object on the picture plane. As a result, we can also begin to consider alternative modes of representation that depart from the traditional drawing or rendering of a project. The single static image freezes and frames an object in one particular view, obscuring the totality of its identity and solidifying the idea that static objects are inanimate. Animations, on the other hand, serve as dynamic picture planes, constantly reframing the object and allowing us to experience inanimate form as dynamic.

What do you think the current state of Thesis is within architecture and how can it be improved?

For many students of architecture, thesis is a critical moment in their education and development as independent thinkers. People frequently describe thesis as a time of “self-discovery”, where perhaps for the first (and only) time in graduate school, the executed project is almost entirely self-driven and is a response to an independently authored brief. The ongoing discussion in schools about the state or even meaning of an architecture thesis is primarily about how or whether the discipline of architecture can distinguish between a thesis and a project. When is a student’s thesis like any other studio project, and when is it something other?

People frequently describe thesis as a time of “self-discovery”, where perhaps for the first (and only) time in graduate school, the executed project is almost entirely self-driven and is a response to an independently authored brief.

In my mind, a thesis is different from a project in three ways: a) it puts forth an argument that contributes to the discipline at large beyond the problem at hand; b) it asks a question rather than provides an answer. I believe a thesis is strongest when it demonstrates the point of interest with various solutions rather than one; and c) it is driven by an extensive research interest.

One aspect of completing a thesis that I believe is not exercised at many schools is writing. I think it is crucial that students learn to write about and document their thesis work in ways different than they would any other studio project. A thesis tells a story and should be delivered as such. Additionally, and on a related note, I think distinguishing between the workflow of a thesis and that of a studio project would be productive. Re-thinking the emphasis placed on the “final product” as opposed to the consistent production of “final” material throughout the semester (or year) might reinforce the notion that a thesis is more about experimentation and the testing of ideas rather than a quest to propose a solution to a problem.

Anthony Morey is a Los Angeles based designer, curator, educator, and lecturer of experimental methods of art, design and architectural biases. Morey concentrates in the formulation and fostering of new modes of disciplinary engagement, public dissemination, and cultural cultivation. Morey is the ...

1 Comment

How do you feel about faceted design, like a geode?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.