The 37 prototypes in Lydia Kallipoliti's The Architecture of Closed Worlds reveal the 20th century’s nebulous relationship with science, ecology and architecture in a way that helps make sense of that landmark era. Their presentation in a single publication also doubles, intentionally or not, as a survey of some of the most unusual and visionary experiments in modern history.

If you are in Los Angeles March 6th, join us at Archinect Outpost from 7-9pm to host Lydia Kallipoliti and her newest book! Kallipoliti will provide a lecture, followed by a book signing. RSVP here. The book can be preordered here.

The 20th century was a remarkable moment in human history. How many inventions, movements, cultures, countercultures, laws and dictums were devised in that era? How can the conventions established and abolished in that narrow time span possibly be counted?

Most importantly, how can we, in the 21st century, make sense of the enormity of events that took place in the 20th to better understand the precarity of our own? Lydia Kallipoliti’s meticulously researched book, The Architecture of Closed Worlds (or, What is the Power of Shit?), partially resolves the questions raised above by highlighting a unique cross-section of its most imaginative experiments; namely, all those that sought to produce spatially closed systems.

The 37 prototypes in Closed Worlds reveal the 20th century’s shifting relationship with science, ecology and architecture in a way that helps make sense of that landmark era. Their presentation in a single publication also doubles, intentionally or not, as a survey of some of the most unusual and visionary experiments in modern history. While Megalomaniacs abound in Closed Worlds, as Walt Disney, Jacques Cousteau and Buckminster Fuller loom large among its pages, it is the attention devoted to the the lesser-known figures that make it a valuable resource, as their contributions to science and architecture were no less significant or brazen.

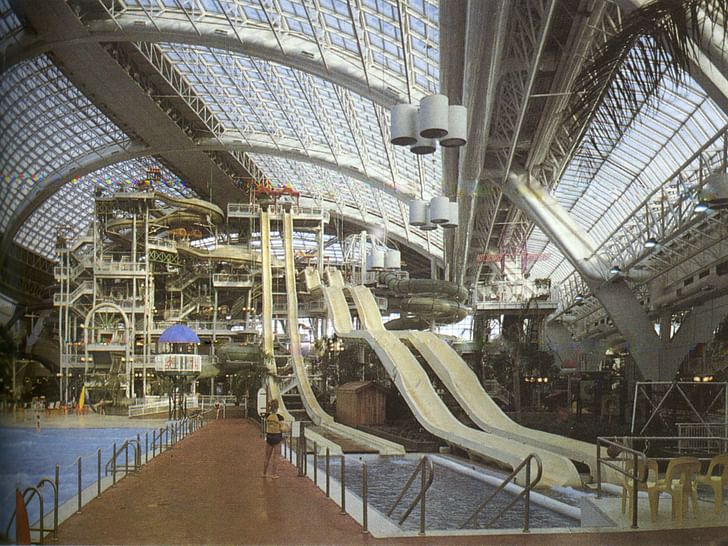

It can initially be difficult to connect the dots between the 37 prototypes, as they might all appear independently spirited at first: how could Auguste Piccard's record-breaking 1928 flight of a hermetically sealed aluminum gondola, Graham Caine’s 1972-1975 experiment to intertwine his family’s waste with an adhoc spaceship, and the Ghermezian Brothers’ 1981 development of a 120 acre enclosed shopping hub all have happened in the same century? With the help of its assiduously drawn diagrams, texts and timelines, I found that the book chronicles three distinct phases of 20th century culture, as each one inspired the next.

The first third of the book is typified by projects which attempted to transgress bodily and technological limitations in the spirit of modern scientific inquiry (1928-1969). Piccard’s gondola broke several records by reaching an altitude of over 51,000 feet; Orval J. Cunningham artificially recreated the freshness or mountain air within a five-story, 900 ton spherical “air-curing” hospital; Jacques Cousteau attempted to augment bodily anatomy with the Aqualung in 1946 and again with the Continental Shelf Station in 1962, a “multistage project to explore and colonise the inner world of the oceans.” At the heart of each of the closed-system prototypes of this era is a desire to both colonize new territories and simulate the colonization of those with “natural” conditions no longer obtainable in typical human settlements.

The second set of projects were designed to explicitly defy the then-burgeoning capitalist systems of the era (1970-1979). Graham Caine’s Ecological House was, according to Kallipoliti, “a grain of resistance against the state’s networks of centralized control, manifest in the distribution of electrical power and sewage networks.” The ten other prototypes surveyed between 1970 and 1979 demonstrate energy independence, with names like ‘Autonomous Dome’ and ‘Liberated House,’ in response to the apparent failures of mid-century consumerism. The first celebration of Earth Day in 1970 and the 1973 Oil Crisis undoubtedly influenced the movement Andrew Blauvelt referred to as ‘Hippie Modernism,” the response to the “struggle for Utopia” made apparent in the previous era.

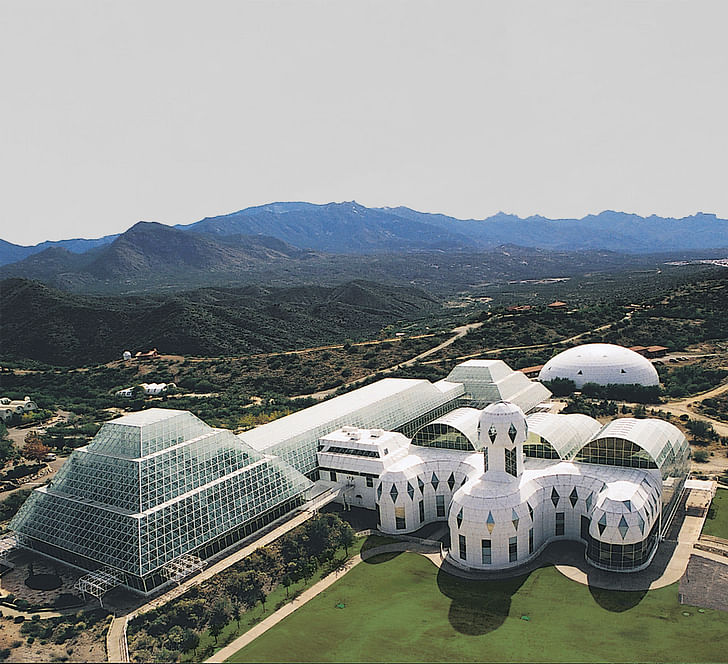

The third set reflects the acceptance and demonstration of a form of capitalism which became increasingly pervasive and more culturally ingrained, often referred to as ‘late capitalism’ (1981-). Biosphere 2, "the largest and most famous closed ecological system ever built" in 1991, may have appeared on its surface as a purely scientific venture, in the spirit of the prototypes featured in the first third of the book. But one did not have to look too deeply into its financial structure to learn that its caused were more dubious and no less indebted to consumerist practices as the 40-block large West Edmonton Mall erected ten years prior. Biosphere 2 and other projects of this era are notable for seeking financial gain while still claiming altruistic intentions.

The description of each prototype concludes with a list of key words, key failures, and elaborate diagrams of energy production and consumption illustrated by Temitope Olujobi. This addendum is valuable material for any readers hoping to improve upon the lessons learned from the remarkable testaments to human ingenuity selected for the book. It is my hope (as well as that of the author’s, I assume) that many readers will look closely at these diagrams and evaluate their own levels of production and consumption as they materialize in their daily environments. The subtitle of Closed Worlds, after all, is a nod to the feeling shared by many environments that we cannot look at the ecological crisis passively; a “raw confrontation” with our shit is perhaps the only solution to avoid the failures all 37 prototypes endured and come out on the other side.

1 Comment

This is an excellent book review. It must have been a challenge to connect the dots of the various prototypes and experiments conducted by completely independent/disconnected people. But the author, Lydia Kallipoliti, managed to do just that. The most poignant observation? The dots are connected because of one common thread: “a desire to both colonize new territories and simulate the colonization of those with 'natural' conditions no longer obtainable in typical human settlements.” It's pretty much saying the earth got screwed up and the ones developing the prototypes were just trying to find a way to fix it.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.