An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture, by Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample of MOS, might be exactly the update needed for the architectural reference book genre.

My formative years of architectural education, well before I enrolled in a degree on the subject, were informed by A-Z architectural reference books. The first few I got my hands on were treasures for my trivia-oriented memory; each one that followed, however, provided less and less new content. With time, the small collection I had amassed revealed a dreadful repetition of essentially the same content: a supposedly objective catalog of biographies, always starting with Alvar Aalto and ending with Peter Zumthor (the older ones ended with Frank Lloyd Wright, of course), with extra spreads and photos to emphasize supposedly important figures in the field. I got sick and tired of architectural reference books before ever becoming an architecture student.

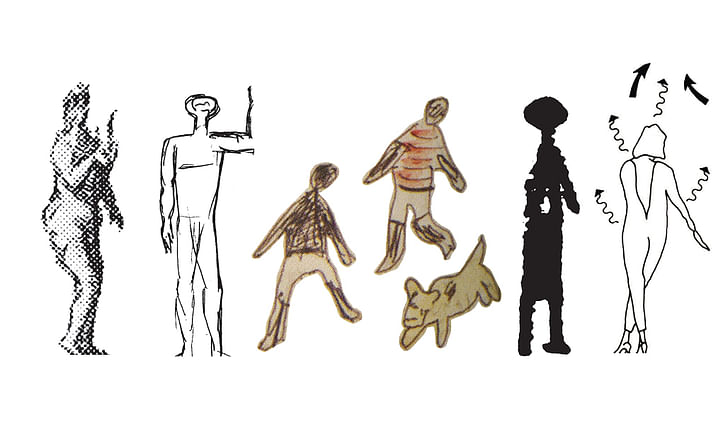

The genre, no doubt, needed a bit of updating. An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture, by Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample of MOS, might be exactly the update needed. Published by the MIT Press, An Unfinished Encyclopedia is exactly what its deadpan title suggests: a well-stocked (yet knowingly incomplete) army of characters lifted from their respective contexts, spanning continents and centuries to stand side-by-side against the unifying emptiness of pure, white paper. No biographies, no dates of birth nor those of death; just the scale figures architects have drawn to sell their proposals.

A wave of excitement may rush over the reader while surveying the 1000+ scale figures in the book’s collection, revisiting architects loved and hated with refreshingly new criteria.

This is an architectural reference book that sheds the information we can all too easily find online and leaves us with the exhaustively excised. A wave of excitement may rush over the reader while surveying the 1000+ scale figures in the book’s collection, revisiting architects loved and hated with refreshingly new criteria. Though these scale figures were placed into their respective images with varying degrees in intention, the invitation to treat each one with the highest possible level of scrutiny is too good to pass up.

What can be gleaned from this book, for instance, is that Bjarke Ingels often envisioned no better model citizen to place against his buildings than Bjarke Ingels, as the architect has apparently placed himself in at least four renderings to sell his projects; Bernard Tschumi almost entirely abstracted the figural body in favor of movement diagrams to describe the human activation of ‘event space; First Office (Andrew Atwood and Anna Neimark) deleted the skin of their scale figures to foreground their attire and postures; Frank Gehry’s figures are, predictably, as scribbly as the scribbly buildings to which they once gave scale.

Like representation in movies, television and the performing arts, the “representations of life” used by architects can reveal how far along members of the field have come (or how far they have followed behind).

Though the introduction provided by Meredith and Sample is intentionally brief (so as to maintain at least some impartiality as a reference book), it does reveal a few significant ambitions: the first is that the book was conceived as a way to collect “various architects’ representations of life;” the second is they view this project as particularly relevant in the current political climate, one “which seems ever more intolerant of difference and increasingly inhuman.” The diversity of scale figures has been a popular subject of analysis when questioning the issue of inclusion in the field of architecture; a close second to the diversity of the architecture firms that drew them in themselves. Like representation in movies, television and the performing arts, the “representations of life” used by architects can reveal how far along members of the field have come (or how far they have followed behind).

This is the conclusion essentially drawn by the slightly longer introductory essays by Martino Stierli and Raymund Ryan, each of whom independently historicize architecture as humanity’s backdrop while ascribing new values to ancillary details. Stierli offers questions similar to those one might ask of Impressionist artists: “What does it tell us of one architect’s understanding of architecture when almost all his scale figures are rendered as properly dressed businessmen? Or when his colleague draws hers as mere silhouettes, ghost-like prescences on the verge of disappearance?” Ryan considers that, “due to a new humanism,” the study of any scale figure can newly indicate “overtly or covertly, dramatically or discreetly, the position of men and women in the society envisioned by the architect.”

The function of An Unfinished Encyclopedia in current discussions on race, gender and representation won’t be lost on its target audience. In an “increasingly inhuman” time, this architectural reference book can rekindle simple lessons overlooked by others of the genre: representation matters, all images and their details are subject to political analysis, and architecture is a human endeavor.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.