Since the beginning of 2018 alone, 857 people have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean — more than five per day — fleeing war, political repression, economic hardship, and ecological crises. It is the deadliest migration route in the world. While the internal borders of the European Union have been made increasingly porous since the early 1990’s, the external borders have been progressively closed off, leaving the sea as the primary path to asylum. But the waters are rough, and migrants are often crammed on overpacked, unseaworthy vessels by opportunistic smugglers. Armed with remote sensing technologies, policing missions sent by the European states send many boats back. Others sink. Rescues — mandated by international maritime law — have become less and less frequent as European countries have instituted a complex set of laws that provide loopholes allowing the abdication of their responsibility. Nearly one in every fifty migrants attempting the journey does not make it.

But it is not only blood that is turning the Mediterranean red. Beneath the surface, the waters are changing. Excesses of urban effluent, rich in nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen from fertilizers, cause algal blooms — often known as “red tides.” Dense layers of phytoplanktons crowd the surface of the water, blocking out sunlight and depleting oxygen. These induce mass deaths of many aquatic species, including fish, harming fishing industries and causing food shortages. Jellyfish, however, thrive in these conditions. As they proliferate, they further wipe out fish populations with their venom. Tourism, upon which most of the coastal Mediterranean depends, drops off. Underwater infrastructure, such as the cooling pipes of nuclear power plants, gets clogged with them, causing costly system disruptions.

the populations that most heavily bear the brunt of ecological crises are the ones most affected by political conflict, while those most at fault are most immune

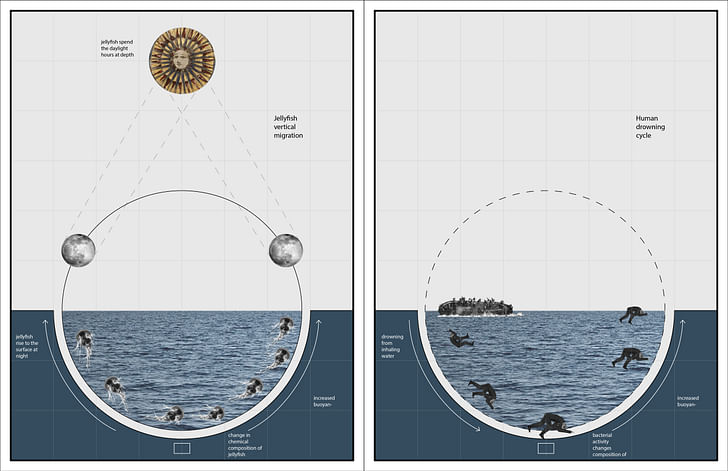

For the Beirut-born, New York-based architectural researcher and designer Ala Tannir, whose project Blood in the Water grapples with them, these two phenomena must be considered together. That is, while seemingly disparate, they both constitute forms of violence fundamentally altering the Mediterranean and figure into a larger global political-economic system in which the ecological and sociopolitical are inextricable. That is, the populations that most heavily bear the brunt of ecological crises are the ones most affected by political conflict, while those most at fault are most immune. The vulnerability of the former cannot be separated from the long history of colonialism also responsible for the security and prosperity of the latter. For Tannir, in order to grasp the complex configurations of contemporary geopolitical power, we must construct new speculative viewpoints that enable us to look at the ecological, the political, and the social together. Only then can we begin to envision alternatives.

Your research engages various bodies — human and nonhuman — at risk and adrift in the Mediterranean. Let’s begin with the former. Can you describe the context of the humanitarian crisis of the Mediterranean at the moment?

Since the early 1990’s, the progressive enlargement of the European Union has allowed the abolition of nearly all internal borders within Europe. This freedom of movement on the inside, however, has been coordinated with the adoption of policies of closure and impermeability of external borders, which has pushed many people to take to sea towards European shores, in order to flee countries in crisis or conflict. In most cases, such journeys are long and perilous. Smugglers have formed networks along migration routes and have established a business from squeezing hundreds of migrants aboard rickety vessels to make the crossings into Europe. In many cases, overpacked and unseaworthy boats lose balance or even capsize. In recent years, European states have instituted various policing missions and remote sensing programs to suppress and push back waves of illegalized migration. They have also installed a set of complex and overlapping jurisdictions to better navigate and exercise control over the maritime domain. These have ironically provided states with legal loopholes to abdicate responsibilities for rescuing migrants in distress, despite that being a legal duty according to international maritime law. As a result, loss of life in the Mediterranean occurs at increasingly alarming rates.

You connect this to algae blooms and subsequent jellyfish takeovers. Can you tell us a bit about these phenomena?

Currently recurrent algal blooms and jellyfish overpopulation are essentially markers of the degrading health of our seas and oceans. And as a matter of fact these two phenomena are actually interconnected: harmful algal blooms are an aquatic ecosystem’s response to excess nutrients in the water, namely overloads of phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural fertilizers, and urban effluent highly rich in phosphate flowing into coastal waters. They indicate a densifying population of phytoplankton—namely diatoms and dinoflagellates—that will overgrow with time, moisture, warmth, and sunlight. These can form dense, visible populations near the water surface. If found in high concentrations, dinoflagellates in particular are responsible for what is commonly known as “red tides.” This represents a condition where the number of certain types of phytoplankton becomes so numerous that it causes harmful algal blooms that lead to a discoloration of the water and turn it red. Ecologically, this action on the surface of the water yields a case of eutrophication in the water column — that is, the overabundance of phytoplankton exceeds by far the abilities of aquatic organisms to consume it.

recurrent algal blooms and jellyfish overpopulation are essentially markers of the degrading health of our seas and oceans

Often times, phytoplankton blooms also prevent their copepod predators’ growth, and hinder their egg-production rates, resulting in large amounts of uneaten algae that then die and sink to the bottom of the sea in the form of waste. It is also worth noting that most herbivorous aquatic organisms will only eat larger algae like diatoms, rather than smaller ones like dinoflagellates. This condition further intensifies the density of decaying phytoplankton in these blooms, and in turn leads to increasing bacterial activity tasked with decomposing this waste. This phenomenon results in the depletion of oxygen in these areas, creating hypoxic or anoxic zones. These are also often called dead zones, since low concentrations of oxygen turn them into areas of mass mortality. While most species are not able to survive these harsh conditions, they do pave the way for more opportunistic species like jellyfish to proliferate. Jellyfish are in fact among the organisms least likely to surrender to the propagation of dead zones. One reason for their resilience is that jellyfish polyps tolerate lower oxygen levels better than other species with high respiratory demands. Another remarkable reason is that in contrast to visual predators, tactile ones like jellyfish are able to feed on smaller copepods that flourish in the presence of dinoflagellates. It is also believed that hypoxic conditions in fact improve their predation abilities as they profit from eating weakened prey. An ecosystem shifting towards harmful algal blooms therefore dictates a food chain that favors medusae, encourages their reproduction, and leads to severe and frequent outbreaks of jellyfish.

How do you humans participate in the increase in jellyfish? And what are the effects for human life and activity?

Well generally speaking, everything bad that humans do for the ocean is actually favorable for jellyfish. Whether it's pollution, warming waters, or deep-sea trawling, humans are providing jellyfish with the perfect conditions to overpopulate the oceans. Also, the proliferation of man-made constructions associated with coastal industries encourages marine species that colonize fastest. They, for example, provide an abundance of new surfaces for jellyfish species to settle onto. Certain jellyfish species spawn openly in the water, and the resulting embryos develop into free-swimming larvae that then require a hard surface to attach themselves to in order to grow. Some polyps actually prefer artificial substrates to natural ones in order to continue their life cycle, bud, and bloom into colonies of medusae. When jellyfish blooms become denser, more frequent, and longer lasting, they interfere with human coastal and offshore infrastructure by clogging underwater cooling pipes for example, which is costly and could cause interruptions in the operation of nuclear power plants or desalination facilities. They can also tip the food chain in their favor, and therefore alter aquatic ecosystems that humans depend on, or wipe entire fish farms with the venom found in their tentacles. And of course they would infringe on coastal tourism which could lead to devastating economic consequences.

What is the strategic operability of connecting these seemingly disparate phenomena? That is, what do you perceive as their relationship beyond the metaphoric?

To me, speculation primarily serves to rethink the relations between the realities humans live in. In one capacity, the Mediterranean Sea is the space that connects the extracting impulses of European states to the raw materials and resources of their “former” colonies in Africa and the Middle East. At the same time, it acts as a bridge for an intensifying migration crisis — and subsequent hyper surveillance. The current mode of visual and knowledge production is then understood as a “space of state control,” as Henri Lefebvre argues. It is as much a vehicle for states to dominate territories and resources, as it is a mechanism for them to extend control over the collective social imaginaries, by prescribing narratives. New and unusual accounts are therefore required to recast dominant ones in order to understand the landscape of the Mediterranean Sea today. Although divided in relation to national interests, the Sea defies the easy legibility of rising global bordering practices. Linking human migration with jellyfish overpopulation then responds to the need to reconnect different threads of violence that tie human displacement together with ecological degradation, and that are often discussed separately.

The challenge revolves around the possibility of contending on numerous fronts without ever compromising the complexity and specificity of the struggle.

Your work operates within an expanded notion of ecology, which blurs the distinctions between human and nonhuman. Can you speak to this? Is there an urgency to disrupting such traditional binaries?

Today, I think it is definitely urgent to recognize the climate as a real political topic. In fact, temperature changes, the depletion of resources, and economic instabilities to name a few do not affect people or species equally, and it is therefore impossible anymore to dissociate ecological phenomena from socio-political ones. Instead, one must conceptualize alternative viewpoints that excite the potential for new political imaginations that dissolve the boundaries between human and natural forces in order to activate the pursuit of social and ecological justice for all species involved. In such a context, it becomes important to reflect upon how global capital obscures the particular in favor of the general, and to bring to vision unjust realities that it simultaneously inflicts on people and nature. The challenge hence revolves around the possibility of contending on numerous fronts without ever compromising the complexity and specificity of the struggle.

In your writing, you invoke the idea of an “interspecies alliance” — can you elaborate on this?

The moment migrants fall overboard and are intentionally abandoned at sea, the underwater world emerges to the surface, and comes into attention. It becomes an enabling agent for an imagined interspecies alliance between susceptible humans, phytoplankton, and jellyfish among other creatures. The speculation here combines drowning forensics, ecological maritime phenomena, as well as apparatuses of surveillance and control. It stretches them across multiple temporalities to expose the same forces of neocolonial extraction that have dispossessed people and rendered them invisible in the water, and are irrevocably disturbing maritime ecosystems by exploiting natural resources. Agglomerations of bodies in seawater cause certain types of phytoplankton—diatoms and dinoflagellates—to densify around them. This in turn results in the discoloration of the water at the surface, a phenomenon visible from space through remote sensing, which in this case then draws multiplying red swirls on a blue bed, and in that sense memorializing through satellite imagery the very same lives that were left to die in the water.

The aim is ultimately to make the revolution irresistible.

In that moment too, as previously discussed, algal blooms provoke a chain of events that lead to a jellyfish takeover of the marine environment, and subsequently interfere with state economies by disrupting previously considered reliable flows of capital. Such obstruction to human industries and capital accumulation carries great political repercussions, since a nation's political stability is tightly knit to its economic performance. This interspecies alliance is envisaged as an act of creative resistance — one that essentially comes to life through design tools. It inquires about the possibility of contesting characteristic abstractions of capitalism by deploying modes of representation to expose, occupy, dispute, and counter politicized and oft-weaponized images. The ambition goes beyond mapping and visualization however, and instead stems from the firm belief in imagination's potential to trace new avenues to inspire change and manifest positive action. The aim is ultimately—and to borrow Toni Cade Bambara's words—to make the revolution irresistible.

Ala Tannir (b.1990) is an architect and designer from Beirut committed to the idea of design as an act of creative citizenship and resistance. She holds a Master in Industrial Design from the Rhode Island School of Design (2017), and a Bachelor of Architecture from the American University of Beirut (2013). She is currently based in New York.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Great Graphics Ala Tannir!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.