Maybe the closest thing to new construction in After Belonging, the sixth Oslo Architecture Triennale, is an apple press assembled with two 2x2’s, some nails, a saw, a gallon bucket, a heavy pole, a colander, a hammer, a plastic bag, a funnel and a car jack. Eriksen Skajaa Arkitekter designed the device after finding an abandoned apple orchard on the eastern edge of the Torshov asylum center, which houses refugees from wars in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries.

“This isn’t architecture,” I heard throughout the opening weekend of the Triennale. And, indeed, there are few models, sections, or other representations of built work in the Triennale*. If one remains committed to the normative understanding of architecture as a fundamentally constructive practice, then this Triennale can be understood as a sort of extended site research. Rather than asking “what is contemporary architecture?” like so many recent -ennials, the Triennale probes “what is the context in which we practice architecture?”

In that, After Belonging responds to an era in which the notion of site specificity must be radically revised. Global trade and information networks alongside novel patterns of consumption and mobility have transformed domesticity into a globalized practice. Emerging corporate platforms and economic structures have fostered new residency patterns and ownership models.'After Belonging' responds to an era in which the notion of site specificity must be radically revised. Climate change, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation raise the stakes of even everyday life. Mass wars and forced migrations alter the definition of both urban communities and citizenship at large.

“Where do we belong?” ask the curators. “How do we manage our belongings?”

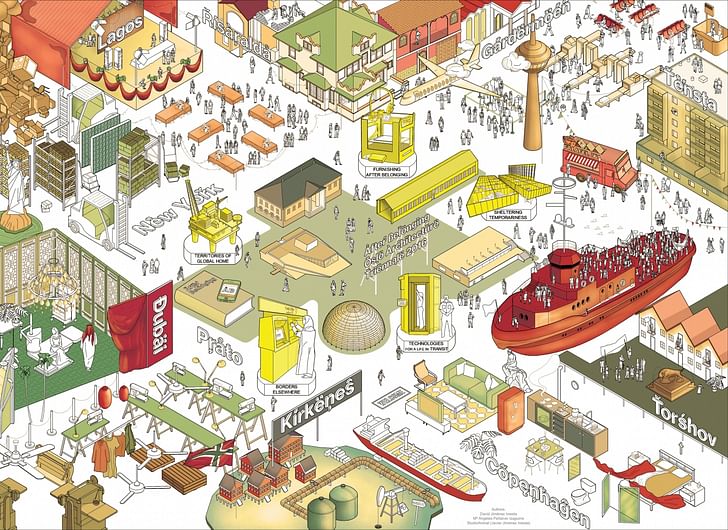

Curated by the namesake After Belonging Agency, the Triennale comprises two exhibitions: On Residence and In Residence. The former, located in the sizeable hall of the Norwegian Center for Architecture and Design (DoGA), houses works that probe this contemporary global condition—a wide-range of studies mapping an equally diverse array of phenomena. The latter, just a quick twenty minute jaunt away in the National Architecture Museum – Oslo, contains representations of five ‘intervention strategies’: commissioned interventions on sites around the world, chosen from an open call.'On Residence' maps the dynamic definitions of “residency,” “residences” and “residents” in a contemporary world marked by transience and territorial reconfiguration

True to its title, On Residence maps the dynamic definitions of “residency,” “residences” and “residents” in a contemporary world marked by transience and territorial reconfiguration, as well as unstable geographies and climates. The Center for Spatial Research maps the routes of internally displaced people in Colombia—seven million over the last thirty years—who have fled their homes trying to escape conflicts between guerillas, the Colombian armed forces, and right-wing paramilitary groups. Meanwhile, Air Drifts by Kadambari Baxi, Janette Kim, Meg McLagan, David Schiminovich and Mark Wasiuta charts the transnational migrations of toxic aerosols, which “drift into new territories and challenge existing regulatory norms and forms of global responsibility”.

Andrés Jaque’s exquisite, HD video work Pornified Homes draws a connection between Victorian hothouse transplants and sex workers in contemporary London who self-exoticize to increase their market value, marking “a shift from an expansive Europe, with an exoticized periphery, to daily co-habitation with layers of sexy exotics”. OMA and Bengler’s collaboration, PANDA, appropriates an activist aesthetic in a wry installation that both critiques the sharing economy and assumes its language, “at once an act of resistance and a business opportunity”. Adjacent physically but strikingly different atmospherically, Monuments of the Everyday, a quiet installation by the collective Sigil, composed of Khaled Malas, Salim al-Kadi, Alfred Tarazi, and Jana Traboulsi, traces genealogies of infrastructure in Syria with a focus on their cultural and symbolic influence, from monuments of the Assad regime to targets of aerial bombardment. The wide breadth of the research exhibited in 'On Residence' pushes against the confines of the exhibit.Their research also produced actual interventions in Syria—a well, a windmill—loaded with both symbolic charge and use-value.

The wide breadth of the research exhibited in On Residence pushes against the confines of the exhibit. While the curators subdivide the show into smaller groupings—‘Borders Elsewhere’, ‘Furnishing After Belonging’, ‘Sheltering Temporariness’, ‘Technologies for a Life in Transit’, and ‘Markets and Territories of the Global Home’—the close physical proximity of exhibited projects sometimes leads to jarring jumps in tone. But then again, so does everyday life in the 21st century, where just a click separates a listicle from a report on the war in Syria.

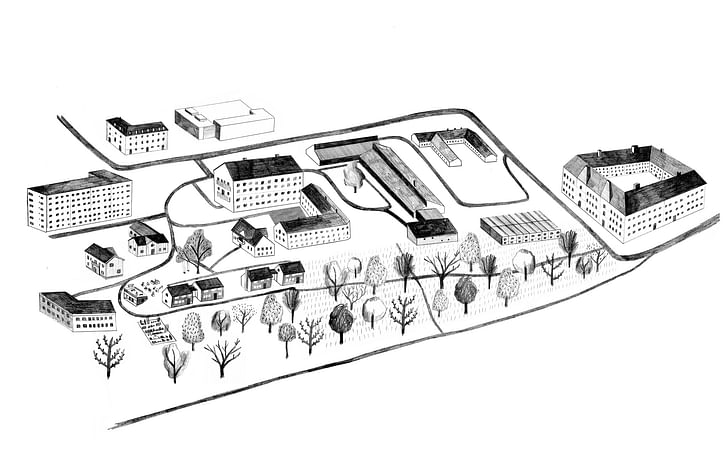

The cohesion of the show was significantly aided by a strong exhibition design by the curators, which continued into the second exhibition, In Residence. This exhibition comprised a series of studies and interventions in the Oslo Airport, Kirkenes, Stockholm, New York, Torshov (Oslo), Dubai, Lagos, Copenhagen, Risaralda, and Prato. Begun months before the opening of the Triennale and slated to continue long after it’s closed, the interventions were exhibited as works-in-progress displaced from their sites and represented through text, image, and an occasional mise-en-scene.Like 'On Residence', 'In Residence' conveys a mix of attitudes.

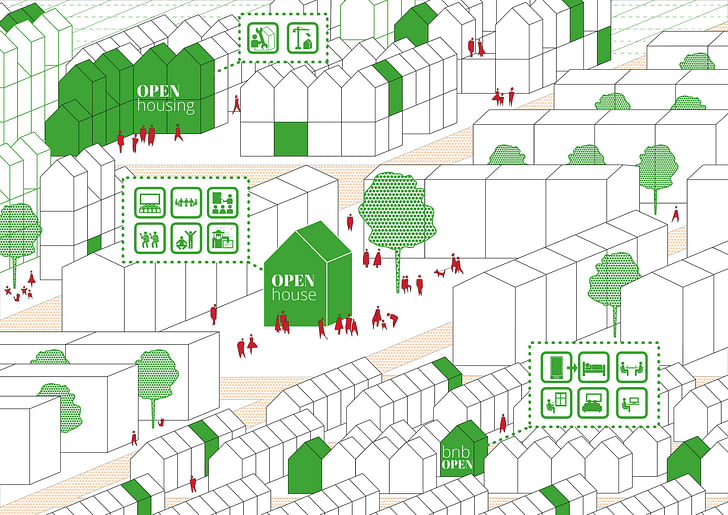

Like On Residence, In Residence conveys a mix of attitudes. OPEN Transformation by Elisabeth Søiland, Silje Klepsvik, and Åsne Hagen includes an app, bnbOPEN, that helps asylum seekers find temporary shelter offered by ordinary inhabitants of Oslo. “OPEN transformation explores alternative ways of meeting asylum seekers’ needs through new notions of adaptability and hospitality, in order to overcome the narrative of ‘us’ and ‘them’,” they write. Working on the same site, Ruimteveldwerk designed a city guide filled with resources in Oslo for asylum seekers. Across the room, another app, Cher, created by Caitlin Blanchfield, Glen Cummings, Jaffer Kolb, Farzin Lotfi-Jam, and Leah Meisterlin, accelerates the sharing economy to its natural conclusion: the minute-to-minute rental of just about any object, even immaterial. “Following [the trends set by home-sharing and short-term rental apps, Cher exploits their logics: a frictional platform unapologetically connecting individuals through things and the scripted language of exchange.” Meanwhile, Bollería Industrial / Factory-Baked Goods made site-specific works in the Oslo airport that humorously intervene in the ritualistic experience of airport transit.

As an exhibit, In Residence lacks much of the substance of On Residence. The projects miss the in-depth research present in so many of works of On Residence, while the accompanying texts feel too short to be of real value. While these strategies did intervene in their contexts, many operated mainly as rhetorical statements, drawing out the particularities and peculiarities of the sites more than radically transforming them or their use. But as a curatorial strategy, In Residence is daring and successful, a major component of the Triennale’s broader achievements. The exhibition serves as the curator’s most visible struggle against the (all-too-present) limits of the -ennial formats.The exhibition serves as the curator’s most visible struggle against the (all-too-present) limits of the -ennial formats. It expands the Triennale’s geographic reach beyond Oslo. It stretches its temporal duration. It fosters architectural praxis rather than mere representation.

But In Residence isn’t the only such effort. The Triennale also put on a marathon of lectures, talks, and roundtables in the Oslo Opera House. The week after the opening, it hosted students from around the world in an experimental academy. During the closing events, the Oslo City Hall will be converted into a temporary “Embassy” that “represents, through cultural means, the ideals of ‘stateless democracy’ developed by Kurdish communities of the autonomous region of Rojava, northern-Syria”.

Together, these projects not only frame the exhibits within a larger conceptual ambition, they also consume an (assumedly) sizeable chunk of the curators’ budget. Less visible than the two exhibitions, these ancillary projects speak to the curators’ best intentions: to do something more with the Triennale format. After Belonging focuses on the context of architecture rather than troubling over its definitions, so it makes sense that the -ennial format itself became a site of design. how can we build on the unstable ground of the present?

Rather than attempting to collect all indexes of a single phenomenon, After Belonging presents various indexes of various phenomena, bound together by shared descriptors (displaced, destabilized, disjunctive). It makes for an unwieldy mass of material, and the visibility of each individual project is sublimated to the larger ambition. But, with some patience, the Triennale begins to cohere around its lexicon. Like with its title, After Belonging operates metonymically—dancing around a definition of the present that is at once intimately familiar and yet hard to pin down with any precision.

If recent -ennials have displayed a hand-wringing crisis of conscience—how can we build on the unstable ground of the present?—it’s in part because architecture remains beholden to a telos-driven rationale. For every problem, there should be an (architectural) solution. And problems are in no short supply. But recognizing a symptom doesn’t always produce a cure, particularly if the cause remains unclear. Hence, an institutional insecurity grips the discipline, which desperately attempts to stake its relevance to its ability to problem-solve, even if the problems far exceed its capabilities. When the foundation begins to crumble, a mud brick wall won’t help.

After Belonging nimbly avoids this trap by looking out more than in, and by deploying architecture’s diverse skillset towards a diagnosis rather than a quick-fix. When the foundation begins to crumble, a mud brick wall won’t help. First, the seismic activity must be mapped. Sometimes, as the curators of After Belonging repeatedly declared, solutions won’t be found at all. However, that doesn’t necessarily prohibit action. While an apple press may not be architecture, or a solution to a migrancy crisis, it can help people feel like they belong—but first you have to notice that there’s an orchard.

For more on the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale, check out in-depth looks at some of the installations and our interview with the curators.

*[Correction] The original article stated that there a "no drawings, models, or sections" of built work in the exhibition. This is incorrect. Some projects, notably City of Islams by L.E.FT, included representations of built work.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.