Fellow Fellows is a series that focuses on the current eruption of fellowships in academia today. Within this realm, these positions produce a fantastic blend of practice, research, and design influence, traditionally done within a tight time-frame. Fellow Fellows sits down with these fellows and attempts to understand what these positions offer to both the participants and the discipline at large. It is about bringing attention and inquiry to the otherwise maddening pace of revolving academics while giving a broad view of the breakthrough work being done by those who exist in-between the newly minted graduate and the licensed associate.

This week, we are talking to D-ESK, the creative architectural practice led by David Eskenazi. David has completed both the Oberdick Fellowship at the University of Michigan and the LeFevre Fellowship at Ohio State.

The conversation, focus and applications to fellowships in general has exploded over the past decade. They have become the go to means of exposure, legitimization within the academia and in some respect the HOV lane of historically PhD owned territories of research and publication. What are your views of the current standing of fellowships as a vehicle of conceptual exploration?

I guess a fellowship is a recognition promoting collegiality and independent work. It’s an environment to work out early ideas and learn about what kind of architect and pedagogue you’ll become. I don’t think the fellowships that architects hold have much to do with the territory of PhD scholarship. I’ve never heard that position before and wouldn’t equate design ideas with historical research. I’m also unsure that fellowships are a “go to means of exposure.” There’s a lot of of fellows not everyone knows. Instagram is certainly a more efficient means of exposure than moving to the midwest. I think of the fellowship as a year to focus—it’s the gift of time and a deadline.

There’s a lot of of fellows not everyone knows. Instagram is certainly a more efficient means of exposure than moving to the midwest.

What fellowship where you in and what brought you to that fellowship?

There were two. The Oberdick Fellowship at the University of Michigan and the LeFevre Fellowship at Ohio State. They were great, but different. It’s like your first and second boyfriend. One was smart and one was good looking. You fell in love with one and had great sex with the other. There was monogamy and polyamory. You made mistakes, you learned about yourself, and they kind of blur together. But, you only have warm feelings looking back. I certainly didn’t come out of it the same way I went in.

Jokes aside, Ohio State has an incredible formalist faculty, and Michigan has a broad array of peer support. Both fellowships were geared for a practitioner, so I thought of the work as baby steps of practice. At Ohio State, I had a gallery to fill whereas at Michigan, the gallery was already full and I made images instead. I also wrote a lot. I went into their archives and used their knife cutters. I learned about their football rivalry. I taught core and optional grad and undergrad studios with great students. Some of those students helped me out. I learned a lot from my colleagues. I still talk to them. They’re much smarter and more talented than I am.

What was the focus of the fellowship research? What did you produce? Teach? And or exhibit during that time?

I’m always interested in something new. That’s really what keeps me excited about all the creative arts. But my sense is that newness and novelty conflated together recently, for better or for worse. Maybe they always have, but it’s indicative of the speed that we expect new work and ideas to pop up these days. As long as there’s a sheen of “never seen it before”, it feels new. But to me, that’s novel. New work in architecture engages some longer term issues architects have been grappling with. In some ways, phase one of the digital project was the exploration and mastery of design tools (usually under the premise of “because we can, we should”, mostly disseminated through magazines then blogs), and it looks like phase two is currently shaping up around the dissemination of work (a shift to the politics of the image and away from design expertise, which is too bad). For me, the question is, how does phase two engender new work, not just novelty?

I learned a lot from my colleagues. I still talk to them. They’re much smarter and talented than I am.

That’s a long-winded way to say that my fellowship research did two things. First, it’s interested in the biases of the tools we use to make new things, such as design and image software. Design software biases scale, interiority, and copies in ways different than previous working methods. Architecture hasn’t yet developed conventions for these biases, as we’re still relying on old models like line drawings (although yucky BIM models exist). The research attempted to make sense of the scaleless, pixel thin, infinitely copyable model through comparative formats: in pairings and series.

The second aim of the research was to produce newness without novelty. The work was clear but also the sum of the project was greater than all its parts. There’s really nothing worse than one-liner work. Some work was joyous, some wasn't. None of it feels like you haven’t seen it, but its working on old problems of part to whole, figuration and geometry, materiality, metaphor, arrangement, interiority, etc. The images are pretty straightforward: here’s something next to something similar.

What did you produce? Teach? And or exhibit during that time?

At Ohio State, I filled the gallery with an installation titled Training Wheels. The project dealt with the size of unstable objects that fill a volume. The drawings of the wheels were as significant as the physical installation, because a large intellectual premise of the show was difference between size and scale, or drawing and object. Since the fellowship is geared towards an emerging practitioner, the installation was an opportunity to critically engage practice through constructing something at the scale of architecture. Everything was maxed out—to the size of the gallery, to the production budget, to the available labor—such that the project rethought construction staging, material acquisition, etc. The studios I taught dealt with similar problems, including a studio where students designed a small, medium, and large building.

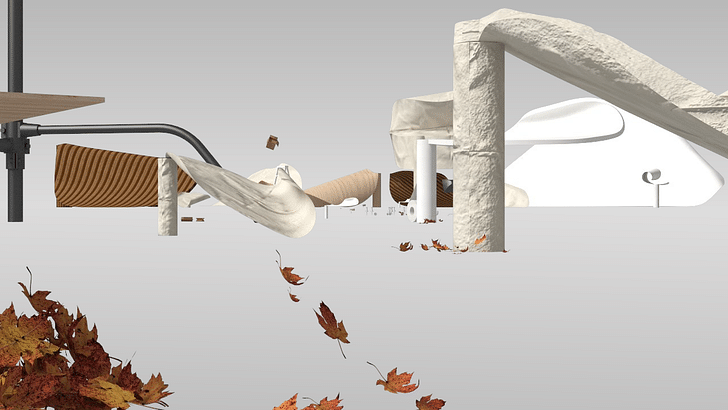

If Training Wheels thought of material as a rigid body, then Column & Canopy at Michigan thought of it as a soft body. Here, gravity is the determinator of scale, as a kind of one to one relationship between material and size. Objects deform as they get larger, then are represented at the same size through photographs and videos. The courses at Michigan moved beyond compositional ideas about size and instead towards techniques of miniaturization and enlargement and design work at the scale of the city.

What negative sides to a fellowship do you see? (if any)

The only negativity I sense comes from voices who look down on fellowships. Haters gon’ hate.

What is the pedagogical role of the fellowship and how does it find its way into the focus and vision of the institution that you worked with?

If anything, the fellowships are a kind of foreign exchange. A stranger enters a school. Pedagogical models are already set in the school and the fellow adapts or changes the discussion. Usually they are the new energy that school year, but like any foreign host, the school will go on after the fellow leaves. Similarly, the students are always changing. So it makes sense anyway, schools are only made of who is there and what they do with their time together.

The only negativity I sense comes from voices who look down on fellowships. Haters gon’ hate.

It seems like there’s a difference between fellows developing their own courses with students who elect to take them compared to joining a core curriculum. If the foundation years set the standard for the student body, then a fellow’s participation has a different kind of influence compared to later, optional courses. In any case, students were excited to work together. They’re the best part.

Where do you see the role of the fellowship becoming in the future and how does it fit within the current discipline of architecture?

This is a good question. I’d be curious to see if the model we have right now lasts another ten years. Maybe schools will be made mostly of fellows. And everyone will say “Hello, fellow fellow.” Can you imagine? The whole curriculum would be led by fellows. That could be a disaster. But disasters often lead to something new.

There is come criticism that a fellowship is a cost effective way for institutions to appropriate potent ideas while leaving the fellow with little compensation besides the year of residence and no guarantee of permanent position? What is your position on this?

I don’t know much about institutional budgets. But the lack of commitment means that fellows are free to do whatever they want. There’s no need to impress anyone there. That might mean no one likes it, or, as is usually the case for me, there’s a long silent pause. So you do you. It’s also possible that you’ll influence your colleagues, and that they’ll influence you. That’s the collegial part of the fellowship, which is the whole point of being there.

What support, and or resources does a fellowship supply that would be hard to come by in any other position? Why would you pursue a fellowship instead of a full time position?

Well, as far as I know, the fellowships are full time positions. You’re there all the time and you’re paid and you’re given a research budget. I don’t think you have to choose. And nothing is forever, so do whatever you want in the meantime. Mostly the resources are the conversations and the structure. That’s all you really need to make work. And great students.

What advice would you have for prospective fellowship applicants?

Be clear and take a risk!

Anthony Morey is a Los Angeles based designer, curator, educator, and lecturer of experimental methods of art, design and architectural biases. Morey concentrates in the formulation and fostering of new modes of disciplinary engagement, public dissemination, and cultural cultivation. Morey is the ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.