What does it mean when a country takes responsibility for a historical act of injustice while ignoring its contemporary actions of a similar nature? In this essay by Suzannah Victoria Beatrice Henty for The Funambulist, she examines the often-contradictory nature of reparation politics.

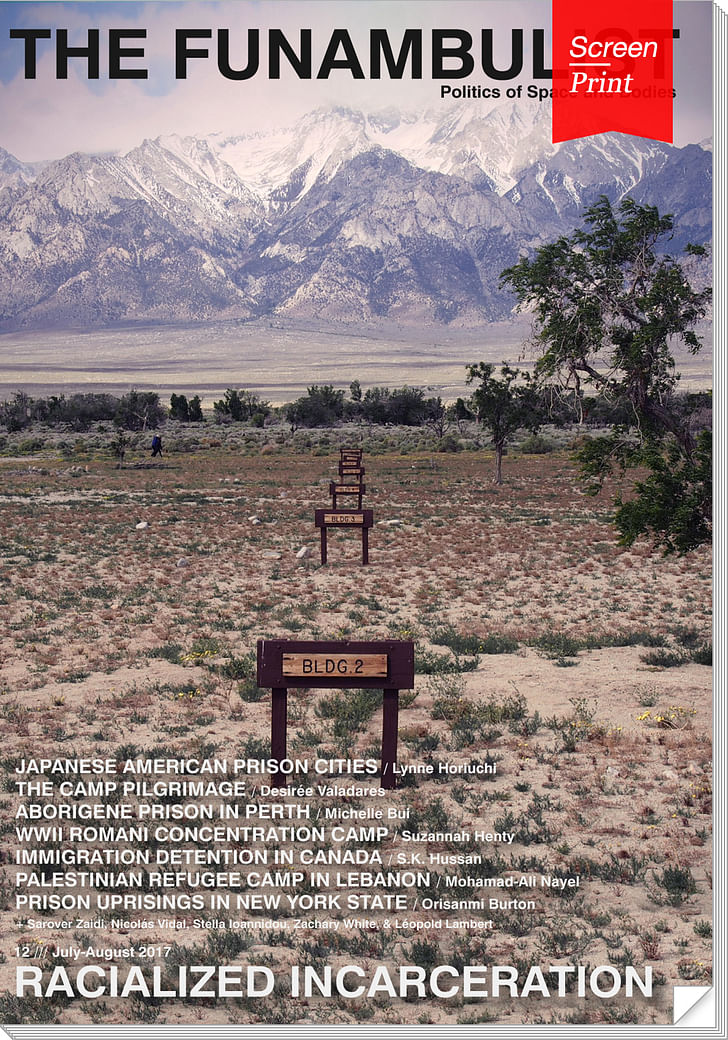

The Funambulist is a bimestrial online and print journal founded by the French architect Léopold Lambert in 2015. Operating alongside a blog and a podcast, The Funambulist critically engages with some of the most pressing issues of the day, focusing on the political relationships between bodies and the built environment. Their twelfth issue focuses on issues of Racialized Incarceration and from the position that architecture is an unsurpassable instrument of its enforcement, attempts to illustrate how the violence of colonial and structural forms of racism endure time and materialize in space.

For this iteration of our recurring series Screen/Print, we are exhibiting an excerpt that discusses the concentration camps for "travelling people" in France during WWII in relation to the contemporary acts of racism enacted on the same group.

The French Porajmos: Roma, Romani, Yenish, Manouche, and Sinti People in the WWII Concentration Camp of Montreuil-Bellay, France

by Suzannah Victoria Beatrice Henty

On October 29, 2016, standing on the ruins of the concentration camp of Montreuil-Bellay in Mid-Western France, French President François Hollande declared to an audience of approximately 500 people, that the camp for “nomads” during World War II would become a national memorial site. Quite literally trampling on the stone foundation of the former barracks with microphones, flags and personnel, where approximately 100 Romani were killed under the Third Republic and Vichy Government, Hollande stated, “the day has come, it is necessary that the truth is said […] The Republic acknowledges the suffering of traveling people who were interned and admits that it bears a great responsibility in this tragedy” (Ouest France, October 29, 2016).

Hollande thus acknowledged the French Government’s involvement in the segregation of Roma, Romani, Yenish, Manouche, and Sinti communities. The manner in which the concentration camp of Montreuil-Bellay was introduced to wider France in late 2016 raises questions concerning the valorization of ruins, places of trauma, and the public, we the witnesses, of how memory is legitimized in history by government authorities. Concerning specifically heritage and patrimonialization, the concentration camp of Montreuil-Bellay represents conflicts within the practical application of the values of contemporary French society and exemplifies the often-contradictory experience of reparation politics. After the war, the French state continued to develop deportation, displacement or accompaniment to the borders of thousands of its “nomad” population policies, perpetuating this long-lasting social exclusion and discrimination. The deportation and demolition of Roma and Romani settlements peaked in 2009–2010, when Sarkozy’s conservative government deported approximately 10,000 Roma people, and it continues today with armed riot police regularly displacing and demolishing settlements. Thus, the treatment of the few ruins that remain of the Montreuil-Bellay concentration camp for “Tziganes” in France, and its existence in the first instance raises two questions: how does the French government expect to wholly acknowledge this ignored painful memory with sensitivity when it continues to attempt to annihilate the presence of this population within its borders? And, when Hollande acknowledged the prisoners of the camp, was he talking only about a population that belongs to the past and not the Roma, Romani, Yenish, Manouche, and Sinti people that live in France today? In the hardening of the right-wing political climate of France today and in the face of a continued state of emergency, these questions are even more pertinent.

The question of morality insofar as accountability, responsibility and exoneration must briefly be mentioned regarding Hollande’s (and Chirac’s 1995 acknowledgement of the deportation of France’s Jewish population) acknowledgement of the Vichy Government’s responsibility for Montreuil-Bellay. On June 1, 1940, the French Parliament and Government retreated to Vichy, Auvergne, central France after fleeing Paris, which was by now occupied by Germany. On June 10, 1940 the National Assembly, faced with the imminent overthrow by German forces gave World War I war “hero” Marshal Philippe Pétain absolute power, thus establishing a new Chief of State of a now collaborative France government. On June 22, 1940, the Vichy government was established when the Franco-Germany Armistice was signed, dividing France into Occupied and Sovereign zones, and on July 11-12, 1940, the Constitutional Acts were signed, granting Pétain diplomatic, judicial, administrative, legislative and executive power in the Vichy government. Pétain remained Chief from 1940 until August 20, 1944, leading negotiations with the Third Reich in the systematic arrest and deportation of Jews, Spanish communities, homosexuals, and “Tsiganes.” Official acknowledgements of painful histories are extremely problematic, as they often ignore the contemporary implications of these events. Hollande, as an official representative of the very institution that permitted and committed these atrocities— i.e., the French government — acknowledged this past trauma, indeed an important and necessary gesture. However, in this acknowledgement of the existence of the concentration camp of Montreuil-Bellay, he did not embrace contemporary administrations’ responsibility in the continued racism and segregation of this minority — a moral position to which each individual must remain accountable —, nor that the government remains, in the words of Derrida, “in all good faith, sincerely” accountable for the social and political implications of segregation.

[...]

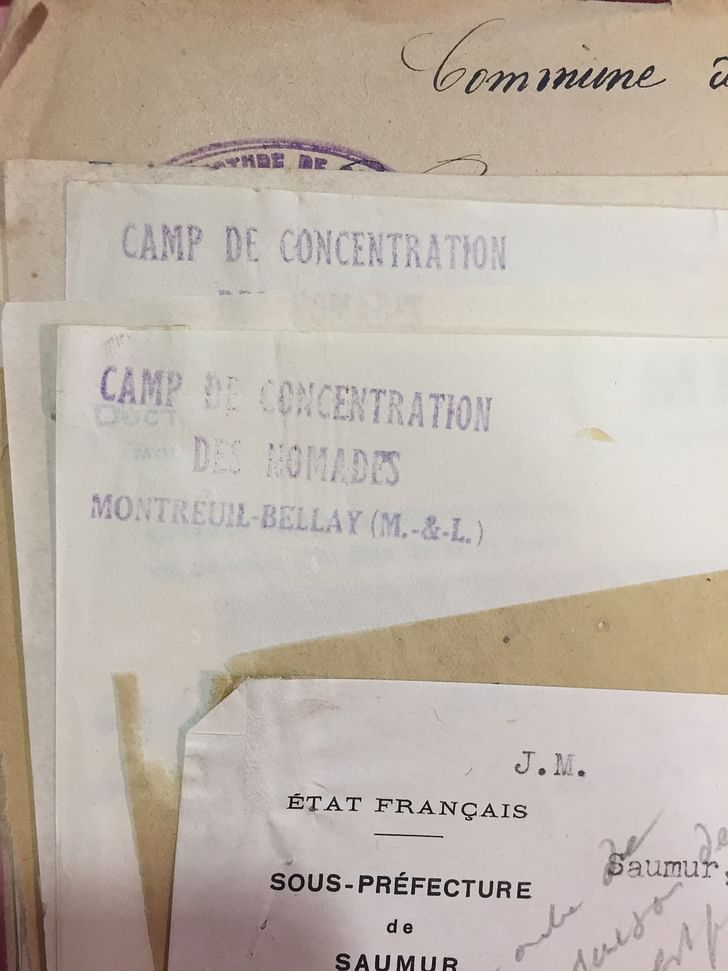

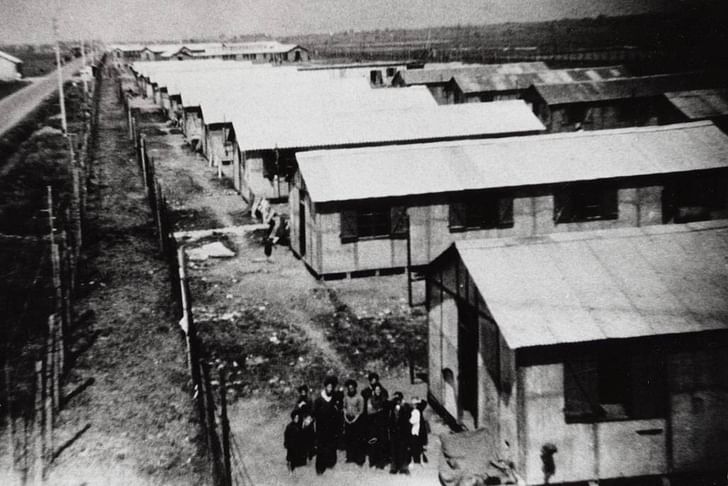

Montreuil-Bellay is a small village of approximately 5,000 people situated 300 kilometers south west of Paris. From January to June 1940, a housing complex was constructed to house the personnel of a nearby factory storing gunpowder, installed on the outskirts of the town by the Ministry of War. With the invasion of France by the German army on May 10, 1940, the camp was occupied by German soldiers and used as a stalag — a prisoner-of-war camp — until March 1941. During this period, German soldiers surrounded the camp with barbed wire and militarized the area. The camp became a camp for “individuals without a fixed abode, nomads, having the type of Romani” (“individus sans domicile fixe, nomades et forains, ayant le type de romani”), French citizens or otherwise, on November 8, 1940. The imprisonment of Romani was the manifestation of Marshal Philippe Pétain’s, the Chief of State of Vichy France, policy that prohibited the movement of all Romani.

Yet, it was not only the collaborative government that implemented this racist policy against “travelling people” — the last president of the Third Republic, Albert Lebrun, on April 6, 1940, finalized a decree proposed in 1938 that stated “nomads” must be gathered in designated communes under the surveillance of the police. In 1885, the French government implanted a census of Roma, counting 25,000 and announced that the police would search for “The King of Gypsies,” (“Le Roi des Gitans”) supposing the existence of a conspiring network. This law was signed and implemented in July 1912. However as French law prohibits the discrimination of people for their ethnicity, the government sidestepped this by concerning themselves with the way Roma live as nomads — an erroneous stereotype in itself. By 1939, Roma and Sinti were officially considered stateless (apatride) and the French government considered stateless populations in France as enemies and traitors of their firmly codified systems of being.

These laws should not be understood as reflection of the views held only by the government for economic, political or racist reasons — the treatment of Romani people by the wider French public is a result of enduring racism and xenophobia that intensify during a period of perceived threatened living conditions, i.e., during World War II. In reading departmental archives this truth is revealed: the archives from Service Historique de la Gendarmerie Nationale, box 12701, BT Limoges, procès-verbal 382 (Feb. 24, 1941), show requests from citizens to the police (gendarmerie) to round-up the Romani in the area, stating, “Nomads…[are] undesirable and their departure is wished for.” Similarly, the documents at the Archives Départementales de Maine-et-Loire: AD49, where one of the most substantial dossiers contains copies of the letters of acknowledgements in the name of the government for the donors to the camp (file 97w, 48, 1942–1944). It is impossible to know if the donations were made with good will to help the people of the camp, but knowing that the camp was guarded by volunteers of the village, the question needs to be posed. More recently, journalist Hervé Gardette questioned the continued discrimination against the Roma and Sinti population, stating that racism towards France’s towards this minority has become “decomplexed” (“decomplexé” France Culture, April 13, 2017). What Hollande failed to mention is that the camp of Montreuil-Bellay is not a symbolic account of the treatment of Roma and Sinti during the World War II, but one mark of the historic and enduring racism against minorities.

[...]

The camp was officially closed in September 1944 after heavy bombardments over June and July 1944, leaving many wounded and killed. Some prisoners were transported to the other camps in the region, firstly Camp de Choisel in Châteaubriant, then to Camp des Alliers in Angoulême, Charente and Camp de Jargeau in Jargeau, Loiret in October 1944, where they were released in June 1946, thirteen months after the end of the war in May 1945. The camp of Montreuil-Bellay nonetheless continued to imprison Roma and Sinti people until January 16, 1945, when the remaining 498 were released. The camp of Montreuil-Bellay later became a prison for German soldiers, many of whom were female soldiers from Natzweiler-Struthof, who were captured by the French Forces of the Interior and liberation armies. Quickly, the camp was destroyed and left to ruin. In archival photographs of the region, we can clearly see the buildings in 1945. By 1959, there was little more than what we see can today at the site; foundation blocks of the building, the prison, and stairs.

Suzannah Victoria Beatrice Henty is a Paris-based Australian cultural heritage researcher, historian and sometimes-curator currently undertaking her PhD in the Philosophy of Aesthetics at the Panthéon-Sorbonne. Her research focuses on how colonial trauma is materially manifested in constructed and natural environments, examining how spaces of trauma hold residual and profound impacts on and in the landscape.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured an excerpt from The Funambulist. Interested in exploring more? Subscribe to the print journal or online version here.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.