This article was originally published on the blog of the Chicago Architecture Biennial, the largest platform for contemporary architecture in North America. The blog invites designers, writers and other contributors to independently express their perspectives on the Biennial across a range of formats. The 2017 Biennial, entitled Make New History, will be free and open to the public between September 16, 2017 and January 6, 2018.

So much of American architecture’s feminist history has yet to be written. Textbooks rarely mention institutions like the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture, for example, which was founded in 1975 to develop new approaches to the “man-made” environment. Not enough architects are aware of institutions like Chicago Women in Architecture, the longest continually running women’s organization in the country, let alone shorter-lived groups like New York’s Association of Black Women Architects. These unsung pioneers deserve a closer look in light of today’s politically charged environment, which has newly inspired architects around the world to work for a more equitable profession.

But no feminist group challenged the status quo as imaginatively as CARYATIDS, a little-known collective of designers founded twenty-five years ago in Chicago. On the occasion of the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial—which will reinterpret ideas from the past under the theme of Make New History—it’s worth looking back at how these hometown trailblazers set an unprecedented example for activism in design.

CARYATIDS (or CARY for short) stood for “Chicks in Architecture Refuse to Yield to Atavistic Thinking in Design and Society,” and its members targeted the boy’s club atmosphere of the design trades with equal doses of candor and sarcastic humor. This is the little-known story of CARY’s 1993 exhibition, More Than the Sum of Our Body Parts, which leveled provocative critiques of the architecture establishment and remains a vivid example for today’s generation of activists in design.

While no buildings were on display, the exhibition sent a strong message about what it means to be a woman in architecture and how the profession ought to respond. A review of CARY’s exhibition in Architecture magazine described how MTSOBP “shatters male myths,” “symbolizes limits,” and “exposes the inequities of pay, position, and power” in architecture practice. A video from the Randolph Street Gallery opening shows a stylish event with artists, architects, and designers enjoying cocktails as a rotating cast of men and women smiled and posed through the cutout face of a caryatid.

CARY was a collective of over seventy architects and designers, both men and women, but three women were at the center of it all. Carol Crandall, Sally Levine, and Kay Janis were all involved in the Chicago Women in Architecture (CWA)—Crandall was just ending her term as CWA president—when they decided to organize a more radical spinoff group in 1992. The following year, Chicago would host a joint convention between the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the International Union of Architects (UIA), the largest gathering of architects ever. What’s more, the AIA’s first female president, Susan Maxman, hosted the historic moment.

CARY needed to reach the upper echelons of the AIA in order to push policies affecting women to the center of the national agenda, and they felt a counter-exhibition was one way to do it. Gender inequities that seemed to disappear during the “boom” years of the late 1980s reappeared as layoffs disproportionately left women out of work during the recession of the early-‘90s. In light of this, CARY sent Maxman a copy of the MTSOBP catalogue with a formal letter that spelled out their demands:

“Dear Ms. Maxman,

… The following issues have been ignored by the AIA:

- The Wage Gap

- The Glass Ceiling

- Family Leave Policies

- Gender Bias in Treatment on the Job

- Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

- Family/Workplace Issues

- Attrition Rates

We challenge the AIA to formulate specific programs and policies to address these issues.”

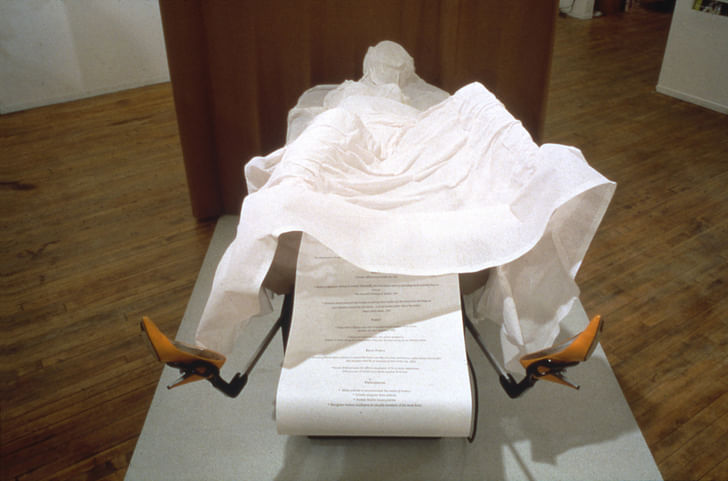

Had Maxman visited the exhibition she would have seen a gallery dotted with large sculptures, each addressing a different aspect of architecture practice. Some addressed problems in workplace policy and ways the AIA could intervene. Just Relax, This May Cause Some Discomfort, for example, was a gynecological gurney covered by a paper printed with the Family Medical Leave Act, which President Clinton signed earlier that year. CARY pointed out that this legislation is ineffective for the 90% of architecture firms with 20 employees or fewer, which remains true today.

Tea and Sympathy displayed the “loosely veiled excuses” that men offered for diminishing women in the workplace. CARY painted a series of teacups with an excuse (“We didn’t reschedule the meeting just for you”) and decoded the underlying reason on the tea tag (“Because you’re a mom”). The piece expressed the feeling of disposability the women felt, with shattered ceramic and mannequin limbs piled in a heap on the floor below the teacups.

Water Cooler Wisdom: If Only These Jugheads Could Talk was more interactive. CARY’s male members recorded the derogatory comments their female counterparts had received in boardrooms, classrooms, and on construction sites. Speakers played these comments above a scene of wire figures with water-cooler heads and dim light bulbs shining within. Visitors contributed their own experiences on a bulletin board reading “Employee Notices.”

The Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune, and the Chicago Reader all covered MTSOBP, as did international publications like Korean Architect. Even if few of the thousands of convention visitors ventured to see the exhibition just a couple miles away, they were likely aware of it. The group disbanded shortly afterward, although each of the three founders continued their advocacy in different ways. Sally Levine staged a similar exhibition, ALICE (Architecture Lets in Chicks Except) Through the Glass Ceiling in San Francisco in 1995.

CARY crystallized in the early ‘90s during the resurgence of women’s-rights advocacy in the US known as feminism’s “third-wave,” several years after the Equal Rights Amendment was defeated in 1982 and the end of the lively “second wave” feminism of the women’s movement before that. In 1993, CARY’s tone surely reminded visitors of the Guerrilla Girls who were active at the same time, challenging the art world’s gender biases through posters, postcards, billboards, and protests filled with puns and revelatory statistics. MTSOBP’s expressive sculpture also recalled an earlier era of feminist art, like Judy Chicago’s vignette-filled Womanhouse in Los Angeles in 1972.

Despite many recent exhibitions touting the impact and work of women architects, few take on larger political questions as directly as CARY did in MTSOBP. In 2010, Woodbury University hosted 13.3% "an exasperated reply to those who say: ‘there are no women making architecture.’” The show borrowed Lucy Lippard's strategy of accepting open submissions through the mail in standard manila envelopes. In 2014, the Storefront for Art & Architecture's Letters to the Mayor exhibition was another cleverly crafted feminist critique, displaying letters by fifty international architects—who happened to be women—addressed “to the political leaders of more than 20 cities around the world.”

As CARY stated in the exhibition with some irony, "The choice of homemaker and home maker is no longer mutually exclusive.” The number of women architects in the US has risen slightly, from 15% in 1993 to 24% in 2016, and the AIA has inaugurated 3 women as presidents since Maxman’s term. As Despina Stratigakos reports, women still drop out of the profession in disproportionate numbers. although newer advocacy organizations like ArchiteXX, the Beverly Willis Foundation, and individual offices like F-architecture hope to change that.

Since 1993, the AIA has also done formidable work addressing equity in architecture through its Equity by Design initiative. The upcoming Biennial itself is also aiming to bolster ongoing progress towards gender equality.

Nearly half of the participants in the upcoming Biennial are female, including 60 women who are principals of their firms. The Biennial will host a roundtable with the Beverly Willis Foundation on the inequities that continue to hold women back in the profession, as well as a conversation with the new Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative that analyzes how class, race, and gender have influenced the production of the built environment for centuries—despite the fact that women and minorities are rarely mentioned in architecture history courses.

Much work remains to be done. Two decades after CARY, the Architecture Lobby continues the fight for fair labor practices in design. The growing organization recently launched JustDesign.Us, an accreditation program to recognize compliant firms. Many architects participated in the widespread Women’s Marches in early 2017. The expanding field of activism in architecture today makes clear that although much has changed in the architectural profession since the 1990s, CARY’s complaints reverberate more than ever.

Sarah Rafson is an architecture writer, researcher, editor, and curator. She is the founder of Point Line Projects, an editorial and curatorial agency. She also sits on the board of ArchiteXX, the New York-based advocacy group for women in architecture, and is an editor of subteXXt, the organization's online journal.

She is organizing an exhibition on the history of activism by women and minorities in architecture, 40 Years Later: Advocacy, Activism, and Alliances in American Architecture 1977-2017, which will open April 13, 2018 at the Parsons School of Design.

The 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial blog is edited in partnership with Consortia, a creative office developing new frameworks for communication. This article also features embedded content from Are.na, an online platform for connecting ideas and building knowledge.

Sarah Rafson is an architecture writer, researcher, editor, and curator. She is the founder of Point Line Projects, an editorial and curatorial agency. She also sits on the board of ArchiteXX, the New York-based advocacy group for women in architecture, and is an editor of subteXXt, the ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.