For all the haranguing and hand-wringing about originality and novelty in the discipline, architecture is, at its core, a remix practice. Most elements in a building have existed for centuries, and the most celebrated “innovations” are usually iterations, fundamentally indebted to a concatenation of predecessors. That applies to structure, but also to form. In other words, there is a language of architecture and, like all languages, every utterance is assembled from a pre-existing vocabulary: at once a repetition and a unique assemblage. A peaked roof isn’t necessary in sunny California—but it still signifies ‘home’. For Lukas Feireiss, the logic of the remix—or, in his parlance, the “radical cut-up”—has suffused his work to the point that even his practice itself is something of a collage of disciplines, straddling the worlds of design, art, publishing, pedagogy, and curation.

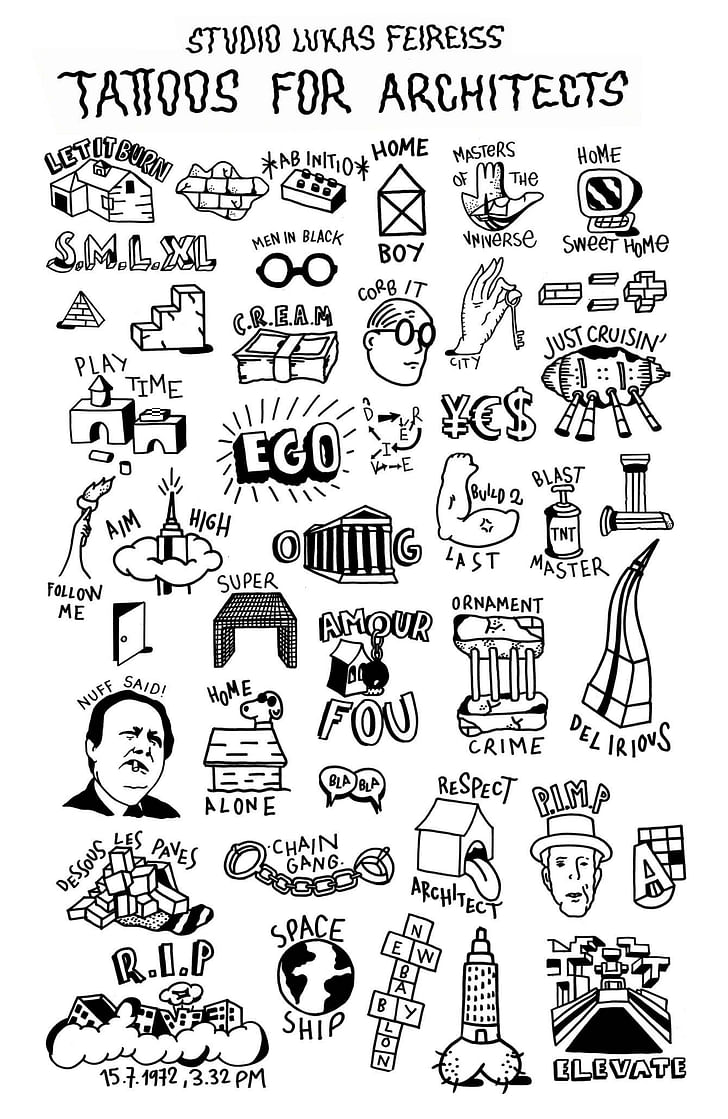

Whether in his writing or his visual practice, Lukas Feireiss likes to mix things up. He freely samples from the work of others—a method he readily acknowledges he inherited from older cultural figures like William Burroughs—in order to create something new. By recontextualizing material, he finds that novel meanings emerge. There’s a playful element to this practice. Feireiss looks at space, as in outer, to analyze space, as in the built environment. In the process, interesting connections arise. For example, Feireiss has written on the way that avant-garde architecture practices from the mid-century, such as Coop Himmelb(l)au and Archigram, incorporated technologies and ideas copied from the nascent space program to imagine new terrestrial futures.

Interestingly, in cutting up and piecing together elements from a variety of different sources, Feireiss has found that the boundaries circumscribing disciplines are porous—but still real and meaningful. A jack of all trades is a master of none, so to speak. “The very notion of inter-, multi-, or transdisciplinarity does not at all mean that everyone suddenly is capable of doing everything,” he tells me. Still, by reframing and recontextualizing existing material, conversations can be instigated and discourse facilitated. Moreover, remixes and copies proliferate even without intention, serving as a dominant paradigm for cultural production post-internet (and even before, all the way back to the emergence of mass media and mechanical reproduction). This is something that Feireiss is busy conveying to his students at the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam, where he heads a master’s program on the “Radical Cut-Up”.

I spoke with Feireiss about the ideas grounding his “Radical Cut-up” methods, as well as the other interests propelling his imaginative practice.

You work between many disciplines—art, curation, design, theory. Is there a shared imperative driving your work across these fields? Do you perceive them as distinct disciplines with their own limitations and potentials? Or as bleeding into one another, so to speak?

I think what connects all of these different fields in my work is a general curiosity to explore different facets of contemporary cultural reflexivity and creativity. My graduate background I actually attained in neither art, curation nor architecture but in comparative religious studies, philosophy and ethnology in Berlin and Rome. During these rather classic humanistic studies, I specialized more or less from the beginning in the dynamic relationship between architecture and other fields of knowledge—from analyzing the architectural language of contemporary ecclesiastical buildings, to investigating the use of concrete architectural metaphors in abstract philosophical writings, and anthropologically questioning the social and spatial relations in the urban environment. I think it’s almost by default that my broadened perspective forces me to see a variety of angles when engaging in the discourse of art, curation and architecture. Within these disciplines there are obviously a lot of overlaps, but there are also very clear and distinct differences that I hold in high regard. The very notion of inter-, multi-, or transdisciplinarity—of which I am a good example—does not at all mean that everyone suddenly is capable of doing everything—perish the thought!—but describes rather the ability to communicate with other disciplines despite and because of the distinct differences between them.

I think what connects all of these different fields in my work is a general curiosity to explore different facets of contemporary cultural reflexivity and creativity

Your work employs a “radical cut-up” method, splicing together images, theories, texts from a variety of sources. Can you speak to the development and practice of this in your work? Were you influenced by the history of collage, William Burroughs, etc.?

Yes, indeed. My work employs a cut-up technique in the sense that it attempts to create new narratives/storylines by means of reconfiguration and recontextualization of preexisting materials. One of my many interests is the critical exploration of space in the widest sense of the term—from the actual physical space of our built environment and the architecture we all live in, and, in recent years now, all the way to outer space and beyond. In my artistic, curatorial, editorial and consultative work I thereby aim at the critical cut-up and playful re-evaluation of diverse modes of cultural production and their medial conditions. The scope of the work here ranges from the overall conceptual development to the design and implementation for diverse formats of knowledge dissemination and visual and spatial communication—such as exhibitions, publications, symposiums, and other events. My personal challenge is thereby always to somehow find individualized narrative solutions for the translation of specific cultural inquiries into a wider societal discourse. For me personally, my upbringing in Berlin—a formerly divided city—, which can be regarded as an urban collage that provides a somewhat unforeseeable city landscape, has had a very strong influence on me. For centuries, plurality, diversity, fractures, contradictions, and inconsistencies make up the eventful history of this city. Since my teenage years, hip hop culture has also been of great significance to me as it can be characterized by an ingenious do-it-yourself approach of creating something out of nothing. The creative activity of remixing and sampling inherent to hip hop culture has since then spread across all disciplines.

How does this “cut-up” method fit into the global production and dissemination of culture today more broadly?

I think that cut-up or collage techniques are amongst the most consequential art forms today. Historically speaking, the emergence of cut-up or collage techniques in various forms of cultural production in the 20th century can be seen as reactions to the rise of new media—whether we’re talking about the explosion of newsprint and photographic reproductions in the early years of the last century, or television and mass media in general from the mid-century onwards. Against the backdrop of today’s accelerated growth of new digital technologies that expand the production and circulation of images, text, sound, and objects in contemporary life in never before seen ways in the history of mankind, the emergence of novel ways of dealing with a vast amount of content of the most diverse type and descent in a creative manner seems only natural to me.

I’m interested in proprietary issues around this. Typically, architects—despite tending to borrow heavily from one another—are strong advocates for intellectual property rights. Can you speak to this?

Obviously the unauthorized appropriation and reuse of content is a hot topic. I personally do not regard the artwork as an endpoint but “a simple moment in an infinite chain of contributions” to speak with French curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud, who investigated in his essay “Postproduction” how many artists today take what has already been produced in culture and, through creative postproduction means, express a new cultural configuration that both speaks to contemporary culture as well as the source material that has been remixed. American writer Jonathan Lethem speaks in his essay of the same name of the “ecstasy of influences“, which embeds a rebuking play on Harold Bloom’s “anxiety of influences” and describes, in a brilliant ode to plagiarism, a refusal of any “source-hypocrisy” and boldly accepts all ideas as second-hand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources. For the field of architecture, Winy Maas of MVRDV—a true collage architect, by the way—recently published his research with students of The Why Factory at the TU Delft entitled Copy Paste: Bad Ass Guide, which attests that computer-based modeling has accelerated the use of copied building designs today all over the world. They regard the internet here as partly responsible for the speed of ideas dissemination, but also observe that conceptual design lacks the specificity of a handcraft. Copying is simply easy, cheap, and fast. I am actually curating an international symposium on the topic called Architecture of Collage at the Berlinische Galerie for this autumn with Gian Pierro Frassinelli of Superstudio, Madelon Vriesendorp, former co-founder of OMA and the artist responsible of the iconic cover image of Delirious New York where two skyscrapers lie in bed, Anna Puigjaner of MAIO, as well as Winy Maas and 2A+P/A from Rome.

the emergence of novel ways of dealing with a vast amount of content of the most diverse type and descent in a creative manner seems only natural to me

You’re leading a program at the Sandberg Instituut oriented around this practice. Please tell us a bit about it.

The new Radical Cut-Up Master’s program I am directing at the Sandberg Instituut, Amsterdam, celebrates the emergence and evolution of the cut-up as the contemporary mode of creativity and dominant global model of cultural production today. It encourages its participants from across all disciplines to copy, combine, create, and celebrate experimental forms of creative production. The interdisciplinary temporary master thereby draws on a broader definition of the term “cut-up“ as a mixture or fusion of disparate elements, or the art of carefully crafted juxtaposition. Within the context of this program, the term is therefore rather a container for a long list of names and actions that describes the mixing and reconfiguration of existing materials to produce new outcomes. Here I basically practice what I preach, and preach what I practice.

Your project Memories of the Moon Age traces a history of human fascination with the moon, reframing the “space age” within a much larger cultural history. What interests you about the moon? What, in your view, is the relationship between our interest in lunar travel and our terrestrial lives?

Correct, the book is the attempt to write a visual cultural history of mankind’s dream of flying to the moon from past, to present, and future. The book explores space travel to our nearest astronomical neighbor—just three days away by rocket—as the ultimate flight of fancy for the human imagination but also as a testing ground for ideas in reality. For centuries mankind has been fascinated by space travel and visiting other planets, but long before engineers and scientists took the possibility of traveling to the moon seriously virtually all of its aspects were first explored in art and literature. The inspirational interdependence between science and fiction, fiction and science lies at the core of the book, which is also an appraisal of the power of imagination and speculation.

Can you tell us about what you see as the influence of this interest in the moon on architecture?

Despite the fact that during the golden age of space travel in the mid 20th century the moon stirred our public imagination, it is now, at the beginning of the second golden age of space travel in the 21st century, clearly planet Mars that does the job. I think that generally other planets and the idea of multi-planetary life still still serves as an object of creative projection and speculation to visionaries across the globe. At the time of the first space walks and the Apollo missions to the moon in the late 1960s, however, new eclectic working methods were established across all disciplines, in particular the arts and architecture, which transformed and redefined existing spatial and intellectual structures. Against the backdrop of aviation in zero gravity, the traditionally static confines of architecture became obsolete. The invention of the spacesuit, in particular, offers a supreme example of the newly discovered possibilities in the provision of basic, stand-alone shelter and protection beyond Euclidean space—insubstantial and protective at the same time. It is no coincidence that singular, small, and apparently floating, pneumatic spaces arised as the signature of a novel, autonomous architecture. Other architectural inspiration during this period emerged from a similar reliance on non-existent technologies, as did the Apollo program at the time of its public announcement. A related tactic within the architectural profession was to adopt spin-off technologies that were actually realized for the lunar missions themselves. Such links can be seen in projects including Archigram’s Living Pod (1966) and Seaside Bubbles (1966), or Coop Himmelb(l)au’s Villa Rosa (1967), all of which share a common “exo-skeletal” scaffolding structure combined with various forms of enclosed habitation units; all are strikingly similar to the designs for the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), which had been in speculative development as early as 1958. Only slightly less recognizable are architectural proposals derived from the possibilities that these new technologies suggest, such as Archigram’s Walking City (1964). These projects recast technologies developed for actual mega-structures: the Apollo launch stack, crawler transporters, and umbilical tower are all mobile, reconfigurable, and massively-scaled contraptions designed to physically move Saturn 5 rockets into their required launch positions.

Architecture shows an impressive flexibility as a partner for the arts

In your work you have a broader interest in collective ‘dreams’—in utopia, in ‘tomorrow', in speculative architecture. Can you speak to this?

Architecture shows an impressive flexibility as a partner for the arts—as subject of investigation, venue for experience, and source of spatial imaginary. This partnership between architecture and the visual arts enriches and broadens our perception of both the built environment and visual culture. Architecture—understood in the broadest sense—has become a highly influential form of imaging in the visual arts, be it as images of buildings and cities, built or unbuilt, real or fictional, hypothetical or actual. On top of this, we live in a culture in which the deliberate blurring of boundaries between the image and the imagined, between fact and fiction has actually achieved an artistic legitimacy in popular culture. Against this backdrop, I have tried to engage in, and encourage the exploration of, the speculative power of these imaginary architectures and architectural imaginaries in many books and exhibitions. I believe that an imaginative practice actively explores uncharted territories. It investigates the role that imagination plays in the understanding of our self, others, and the world around us, and in the representation of past, future, and counterfactual scenarios. Speculation focuses on the act of artistic invention through imagination. Even scientists always begin their investigation by pure speculation and imagination that is often not expected to materialize in the near future. Like science, artistic imagination is experimental, but in a way that prominently recognizes invention and attempts to establish new forms of knowledge. Architecture and the city, as a media of artistic imagination and speculation, can often be read as visual manifestations of deeply personal, intellectual, social, economic, political, and cultural modes of perception and representation. In varying historical contexts, its imaginability can encompass the creation of environments that radically challenge concepts of the real, and serve as a guide to unknown possibility.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.