“What does it take to make a house a home?” asks Bernard Friedman, editor of the newly-released book The American Idea of Home: Conversations About Architecture and Design. Featuring interviews with thirty of the most significant architects practicing today, the volume probes the meaning of home past and present, as well as the role of architecture in constructing it, particularly during an era when most American homes aren’t designed by architects at all.

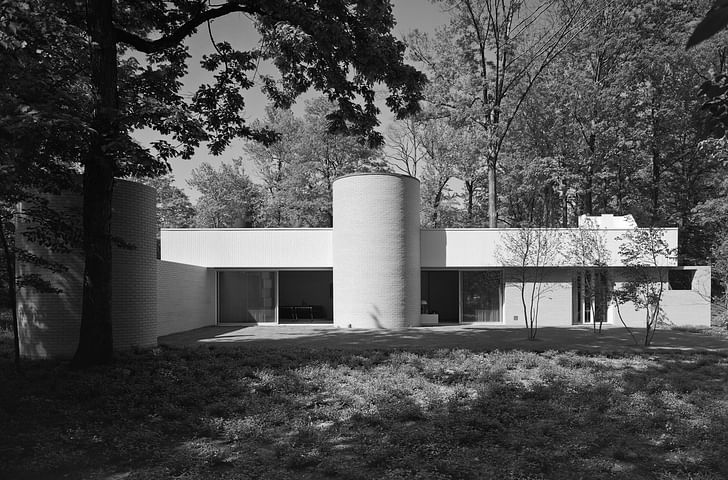

For this iteration of our recurring series Screen/Print, we’re featuring an interview with the Pritzker Prize-winning architect Richard Meier from The American Idea of Home. Meier, born in 1934, is known primarily for his major institutional commissions, from the Getty in Los Angeles to the High Museum in Atlanta. But, as Friedman notes in the introduction to the book, the architect spent a sizable amount of his career designing residential architecture—both at its nascence and today. In fact, his first building was a home designed for his own parents. The Smith House in Darien Connecticut, built five years later, launched him into the spotlight.

“Architecture is a tradition, a long continuum,” says Meier. “Whether we break with tradition or enhance it, we are still connected to that past." In the following interview, Meier discusses his influences, chiefly Frank Lloyd Wright—who is likewise cited by almost all of the designers in The American Idea of Home. At the same time, Meier expresses fervent support for contemporary architecture, which he believes escape the confines of national identity. “I don’t think there is an American architecture,” he states outright. Ultimately, when it comes to the design of a home, Meier believes it must be oriented around the “human scale”.

Richard Meier

Interview conducted by Bernard Friedman

Which architects have influenced you the most?

Probably the most influential residential architect, in terms of ideas, is Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright did more houses than any other architect I know of. And he had an enormous influence on people’s understanding of what residential architecture could be. Not that they followed Wright or designed like him, but the quality of Wright’s architecture is amazing, and that has to do with the quality of human scale and the way in which you move through and experience space. The spaces in Wright’s architecture were very small and confined, not like the huge mansions you see being built around the country today. They were refined and well-defined spaces, and they had a wonderful quality about them. When I think of Frank Lloyd Wright and all that he contributed to American architecture, it’s surprising that what we see today takes so little of his influence and uses it in a good way.

H. H. Richardson did some extraordinary residential work. Stanford White’s houses are famous and influenced a whole style of building in this country, especially in the East in the early part of the twentieth century.

Each era is different, and I think today people are interested in more openness, transparency, and freedom of movement than existed fifty or a hundred years ago in residential design. So today’s houses indicate a different way of living, with less maintenance. They set up a relationship between interior and exterior spaces that allows for ease of movement from inside to outside. And they are more responsive to the nature all around. Nature is ever changing—the color of the light changes throughout the day, the color of the season changes. But architecture is static, inert, and that creates a dialogue between the human made—architecture—and the organic and dynamic—the natural world.

What are your favorite styles of architecture?

My favorite style of American architecture is the style of the moment, which is contemporary architecture, modern architecture. It suits our way of living today in terms of our transparency and openness and in terms of its relationship to nature, the way in which the scale and the light are composed, experienced, and inhabited.

And pre-1900?

Pre-1900 there wasn’t much architecture in America. There was architecture in Europe; architects made palaces and large-scale residential works. But architecture is really a late-nineteenth- or twentieth-century phenomenon in this country. Up until the twentieth century, American architecture borrowed heavily from European styles, but it also had its own indigenous quality in terms of the work of architects such as Stanford White.the international influences on the architecture depend a great deal on the particularities of a place

Do you think there is an American architecture today?

I don’t think there’s an American architecture, no. I think that the work you see in the United States is like the work you see in Tokyo or Shanghai or any other major city in which big architecture firms are practicing. In Berlin and Frankfurt, there are as many buildings by US firms as there are in major cities in America, and maybe even more so in places like Beijing. I don’t think there is an American architecture. American architecture has been exported to influence the rest of the world.

How has globalization changed architecture?

The speed of communication is such today that when a young architect in Argentina completes a work, it’s not only seen reproduced in publications in Argentina, but also in publications in America, Europe, and elsewhere. What’s interesting is that the quality of the workmanship and the materials used might be indigenous to Argentina, but they’re not foreign. The stonework looks like one would use stone in France or Minnesota. What may be lost is a recognition of place through the architecture.

Nevertheless, I think that certain parts of the world still maintain a regional architecture. If one thinks of residential work in Switzerland, for example, especially in the mountains, all the houses have pitched roofs, because the snow load would be too heavy for a flat roof. However, in other parts of Switzerland, you will see flat-roofed houses. So I think the international influences on the architecture depend a great deal on the particularities of a place.

Do you think regional architecture will die out completely at some point in the future?

I think that it depends on what region you’re talking about. Some regions of the world are very dependent on local customs, materials, and ways of building. Much of the residential architecture in the Middle East and Africa, for example, is made out of adobe—mud huts, as it were—because that’s what people can afford. In poor countries, the housing is often makeshift. It’s not really architecture; it’s what’s affordable.

Do you think the globalization of architecture is a good thing?

We live in a world culture. It’s the same with everything, not just architecture. The television programs that you watch at night are the same television programs that people in Abu Dhabi and Moscow watch, so it’s not as though our lives are so different. The physical and political climate we live in is different. But information travels at such a speed that regionalism and nationalism no longer exist as they once did.

In America, the kind of regionalism we saw earlier in the century is less prevalent today. A building in Michigan is not any different from a building in Louisiana or Texas. The styles of architecture have less to do with regional characteristics than they do with individual tastes and desires.

How has the relevance of the architect changed in recent years?

Culturally, there is a greater awareness of and interest in architecture and what is good architecture than there’s ever been before. I think this will continue, and as a result, the quality of our built environment will improve. People appreciate quality and are willing to go out of their way to experience it. For example, when we travel, what do we do? We go and look at architecture.

But when we think of the private residences that are built across our nation, a very small percentage is actually designed by an architect. I don’t know the exact figure, but the majority of homes are put up by developers as part of suburban subdivisions. One would like to think that architecture, when it’s good, influences even the work that is not done by architects. But I’m not sure that’s the case.

A lot of the houses designed by developers and contractors are based on older styles of American architecture.

In order to give people a choice, they’ll do a pseudo-Tudor house, pseudo-colonial house, pseudo-contemporary house, and God knows what else. But it’s just changing the front door appearance while keeping the same basic organization of the building.

How has technology affected residential architecture?

Architecture and technology probably have a greater relationship in larger-scale buildings—office, industrial, and commercial buildings—than they do in residential buildings. Residences are still, for the most part, built one at a time on a fairly small scale. Also, the building codes are such that houses can be built rather inexpensively, when they’re made out of wood, whereas an industrial method of building is by and large more expensive. So I don’t think technology has been as important in residential architecture as it might have been. But it certainly has affected what goes into the house, in the mechanical systems, kitchen appliances, and sound and video systems. Technology has manifested itself in the things we use more than in the spaces we inhabit.

There’s a lot of bad architecture, but it’s not something that one can change.What things would you like to see change in architecture?

I would like to see more good architecture. There’s a lot of bad architecture, but it’s not something that one can change. It happens through education, appreciation, and awareness. I think New York is changing, for instance. The residential buildings are getting better because people realize they can make more money if they do a good building than if they do a mediocre building. Sometimes things change because of necessity, and sometimes things change because of economics or political interest. Cities like Shanghai change because the economy of the country has changed, creating a need for more and more work and residential space. Most cities that are viable and active undergo constant change. That’s one of the things that make New York so fascinating.

What makes a successful house, and has that changed over time?

Architecture is a captivating subject, and people have been and will continue to be fascinated by other people’s homes. What happens in architecture today influences tomorrow, and people are constantly looking and thinking about how to change the way they live. But most importantly, the best residential work is that which is accommodating to and understanding of human scale. And that doesn’t change.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured the introduction to The American Idea of Home: Conversations About Architecture and Design. Find out more about the publication here.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.