Making the leap from paper to brick and mortar (or from the screen to IRL) tends to require a fair amount of financial support. Back in the old days, that would mean a wealthy patron like a Medici or a Guggenheim. And today—well, it also usually means a wealthy patron. For big projects, like a BIG tower, they’re often developers. But, as every architect knows, few developers actually support innovative design. Enter someone like Ian Gillespie, the founder of Westbank and the backer of many significant projects by major architects, from Bjarke Ingels to Kengo Kuma.

Gillespie founded the Vancouver-based Westbank Projects Corp. back in 1992. Since then, they’ve worked on more than $12 billion worth of projects across Canada, the United States, and Japan. They’re known, in particular, for pioneering ecologically-minded design—Westbank is one of the world’s leading LEED Platinum developers—and the architects they employ in the process. Westbank has also supported many significant public art installations. Most recently, they purchased the Serpentine Pavilion that BIG designed last year, a project they had supported from the very beginning.

For Gillespie, developers have a responsibility to bring quality design and culture to their cities. “Development is kind of the most local of all businesses,” he tells me over the phone. “At the end of the day, we will just pick half a dozen cities that we will go very deep in. Those half dozen cities are all chosen very consciously as being cities where we have the ability to have some kind of broadcast effect, so that the work we are doing is more important than just that specific project.”

I talked with Gillespie about his work with Ingels, his support for the arts, and the civic value of good design.

What prompted your initial support for the BIG pavilion and have you supported other Serpentine Pavilions before?

No. I mean I knew the program quite well, just from being in London quite often and from working with some of the other architects who have been involved in the program, like Toyo Ito. So when it came up in a meeting in my office here, Bjarke and Thomas [Christoffersen] and his team were in—I think we were probably working on combination of King Street, which is in Toronto, and a project in Vancouver on Beatty [Street]. At the end of that conversation, Bjarke brought up that they had been approached. It’s not uncommon for the Serpentine, when they choose the architect, to say, ‘Hey, do you have any...patrons who might have an interest?’

When it first came to me, we jumped right on it and they then handed off the discussions between the Serpentine and us while they went ahead and finished off the design…We were involved right from the early stages. And it was a fun project; it’s not that unlike a lot of projects that we work on. We are pretty different from what you would think of from a development perspective. I’ve done 32 major public art installations, working with a number of Turner prize-winners [and other artists, including] Diana Thater, Stan Douglas, Liam Gillick, Doug Coupland, Zhang Huan.

We put a lot into our public art, so it wasn’t big stretch. We are also into a lot of other things, like I have a major vintage couture collection, we have music venues, and I put on exhibitions quite often. We just finished one called Japan Unlayered, which we put on in one of our hotels. I am putting another exhibition on in September, another exhibition on at the end of the year. So we thought of the Serpentine as being kind of an extension of the exhibitions that we put on.

One of the things that really caught Bjarke’s attention was the idea of the pavilion having an afterlife

One of the things that really caught Bjarke’s attention was the idea of the pavilion having an afterlife, and I think that’s what you could say is the most exciting part of our collaboration: the idea that it doesn’t end up in somebody’s backyard of their summer house [but instead] it ends up in a very public space in multiple cities. And, as it moves to those cities, an exhibition is put on inside it, so it’s really used for what it was designed to be used for. And then it will find its eventual home back in Vancouver.

I want to circle back later to your other projects, but while we are still on Bjarke I was wondering if you could tell me more about how you’ve planned for the Pavilion to be used, particularly when it’s permanently installed? What type of exhibitions will it host?

We have like a city block here [in Vancouver] on the water where we put on a number of different things. For example, I’ve got a Liam Gillick piece installed here, I have an Omer Arbel piece installed here, I have a Diana Thater piece installed here, I have got Kengo Kuma doing a new Starbucks in the base of one of the buildings here. I also have a number of major exhibitions going on at the hotel at any given time. I’ve got a Zhang Huan piece here. So there is a public plaza besides the office building where my office is that we’ve built and developed and, on that pavilion, that’s where the permanent home will be for the Pavilion. It’s right across from where the Olympic medals were presented, so it’s the Olympic Plaza. It’s very, very public and it’s right on the waterfront.

What we will do is we will have an exhibition there that will run for probably about 6, 7 months out of the year and every year it will rotate into something new. You could imagine those exhibitions being anywhere from—well, we put on one exhibition, for example, called Gesamstkunstwerk and it was based on the idea of how does the total work of art manifest itself in city-building. [A future exhibition] could be on sustainability as we are the energy provider for the downtown peninsula. It could be on fashion as we have this interest in fashion. It could be on music. It could be architecture. It could be on a particular architect each year—you can see it kind of rotating like that.

What interests you about Bjarke’s work in particular?

We started working with him when they were a very tiny firm. They were just first looking at opening an office in New York at the time. And [Bjarke] came to Vancouver to put on a lecture. He was invited to Vancouver by our then-Director of Planning, Brent [Toderian]; we have this history of doing this in Vancouver where the world’s top notch talents are invited in and part of their [invitation] is that they will get introduced to a developer who might be interested in their work. And I am the kind of developer that is going to use that type of talent. So usually they end up here.

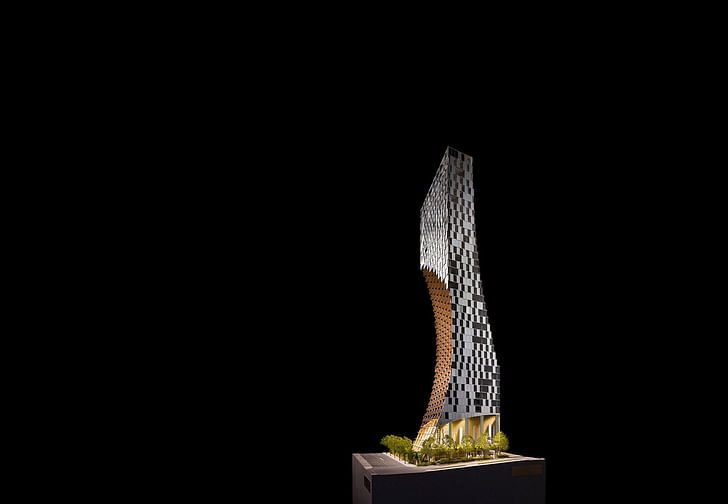

In his case it was a meeting with his laptop computer and just taking me through his work. Thirty minutes into it I said fantastic, we will do a project together. And I had a project actually in Toronto at the time and it moved from that project in Toronto into a project in Vancouver called Vancouver House, which is now under construction and sold out. It was an amazing success.To some extent, it doesn’t necessarily makes sense from a business perceptive doing a lot of these things It sold in 16 countries around the world and it won high-rise of the year in Singapore and it’s really outstanding work. So that was our first project and then we’ve got another office and residential project they’ve designed for us in Vancouver, which we are [working with] the city on the rezoning of. They’ve got a power station here in Vancouver that they’ve designed. They’ve got a big project for us in Calgary that is like 28-stories in the air right now, about half built. Another project in Toronto and then we are now about to start working on a project with them in Seattle. So they’ve become one of about half a dozen architects that we do multiple projects with. I have five or six projects with Kengo Kuma right now, Bing Thom’s office, and then some local Vancouver architects.

To some extent, you know, it doesn’t necessarily makes sense from a business perceptive doing a lot of these things, but I’ve been fortunate enough to have a successful business that allows me to play a little bit, and we think of ourselves as being as much interested in cultures as we are in building things. But what’s different about it, because we are in the business of building things, we actually get to, you know? They are not just ideas in someone’s head; we actually do them... I get to work on some pretty cool things that allow me to grow and to have a pretty big impact on the city. That’s now spreading to Tokyo— we have two projects in Tokyo going up now. We’ve got four projects in Seattle going up, half a dozen projects in Toronto and about a dozen here in Vancouver.

What do you see as the civic value of these notable architecture and art projects?

I think so much of city development is a pretty archaic business. When you think about the phone in your pocket and what that phone looked like 20 years ago, and then for some reason to think that buildings that were often designed 20 years ago are getting built today—it’s like how the hell did that happen? … We think there is a lot of room for improvement, so it’s a scenario that needs a serious dose of creativity and that’s where we see our role.

We’ve got over $20 billion projects going up right now, so we are not a small developer, but, as you know, development is kind of the most local of all businesses. At the end of the day, we will just pick half a dozen cities that we will go very deep in. Those half dozen cities are all chosen very consciously as being cities where we have the ability to have some kind of broadcast effect, so that the work we are doing is more important than just that specific project. For example, a lot of the projects that we do in Vancouver, it’s covered and seen by people from around the world because they come here to see the work that we are doing. A week doesn’t go by where I don’t have somebody, some professor, architect or mayor … coming into my office to have a conversation about it. And I think that that’s where we see our role.

if we are not constantly stimulating ourselves then I don’t need to be doing thisThere is an economic value as well, I imagine, at least in the production of cultural capital.

For sure. I mean it manifests itself in a number of different ways. I mean when you think about it, our typical project is, say, half a billion to a billion dollars and there is a lot of social capital that is wrapped up in these projects. You have a responsibility to be constantly replenishing that social capital. So there is that element, I guess, that is kind of the commercial way of looking at it.

But part of it is very personal—in the sense of, how does your own personal journey fall into this whole thing? I mean if we are not constantly stimulating ourselves then I don’t need to be doing this. I think that that’s probably as much as anything else. It’s just what I enjoy doing.

Who would be your dream architect to work with (who you haven’t already)?

Well we spent quite a bit time with Ando. I had him come to Vancouver and put on a lecture with me here. We’ve had conversations off and on on a couple projects; it just hasn’t come to fruition yet. But I am sure we will do something with him quite soon. Same with Toyo Ito—we’ve been working on a project off and on for the last few years. Jean Nouvel, I think, would probably be right at the top of that list. We have a project in Vancouver that we are going to be reaching out to him [about] this weekend. Renzo Piano I think would be on that list. Obviously Herzog.

But I do have a pretty strong affinity to the Japanese architects… When I’m in Japan, which is [about] once a month, it’s partly for the work I am doing with Japanese architects here in North America, but it’s also for the work I am doing in Tokyo itself.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

I would love to see him work with Ando

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.