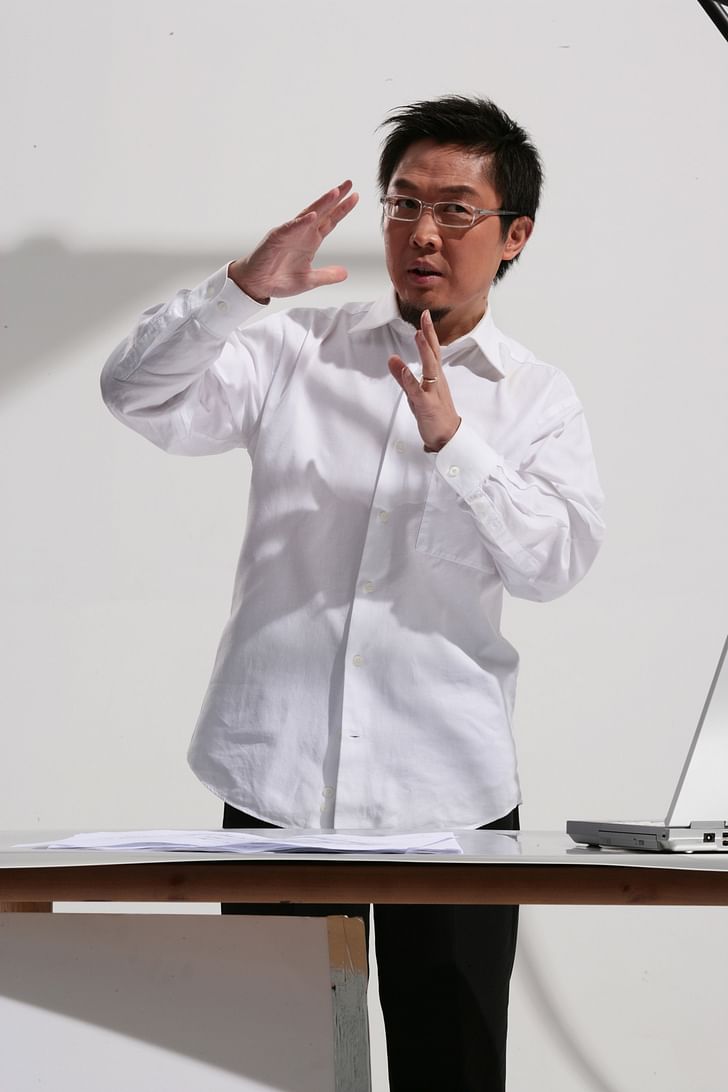

Qingyun Ma, Dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Southern California, cares more about preserving what’s right with the school, now celebrating its 100th year, than his own signature.

Named by BusinessWeek as one of the world’s most influential designers, Ma founded his practice MADA s.p.a.m back in 1996. While his firm is known for its formal innovations, when it comes to pedagogy, Ma cares more about what works than what stands out. And, at USC, that translates to a focus on helping students move from academia to the professional world seamlessly—something that you won’t find at every architecture school. For this iteration of our ongoing series Deans List, Archinect spoke with Ma at his office on the sunny, Southern Californian campus to hear more about how he has guided the school since he became dean back in 2007.

How would you describe the pedagogical stance of the USC School of Architecture?

The program is deeply rooted in the profession. In other words, architecture is conceived of as endeavor to build physical space and place. At the same time, we are considered with the social impact of building and also advancements of technology. Those are the kind of the agenda of the program.

What kind of students do you think would flourish at USC and why?

Students who are deeply concerned with globalism particularly in the built environment. Students that have a good sense of urbanism, in other words how not only a single building but how buildings [together] form the life of a place. Students with these concerns and with a very intense drawing and making capability will survive, will thrive.

Would you say theory plays a major role?

Theory in this program is really to enhance and [develop] a deeper conviction of what the students and the program do. It’s not primarily humanity and the theory studies, it's a professional degree and with true architecture as the focus—in other words, physical buildings.The program is deeply rooted in the profession

What are the biggest challenges academically and professionally that your students face?

Academically, I think what’s challenging is how research and new technology are forming the new way of design versus how societies see their traditions. In other words, what I'm saying is [that] technology and the global agenda really pushed building forward to a futuristic stance. But the societies we're living in are still primarily quite conservative. So this is the academic intellectual challenge that students are facing. You said a second challenge—

Professionally.

Professionally it's related to that as well. Most offices are formulated to really accommodate the needs of a building, which is very practical. But I think for a designer, the true passion is to foresee a future that's not yet fulfilled or realized. So there's a certain… look towards what the future could be in the design practice. But then a profession is primarily meeting practical needs. So [that creates] challenges since the large offices, corporate offices, who do buildings that are, as I described, primarily meeting practical needs, are hiring a lot of students…

We're teaching students who really embrace the future. But the professional world is hiring students who can just do whatever they are asked to do. That to me is the fundamental challenge.

How do you help students find employment after graduation?

Again it is largely conditioned by the market, how the market is being formulated by the whole economy. [Our] professors are [mostly] practitioners. They expose our students to a very open field of opportunities. So the students get a sense of what the practice world is like through the program by collaborating with our professors. The second would be through our professional practice. There is a cluster of courses that are formed on the practice of architecture, meaning legal, contractual and financial.

So there's a cluster of classes that enable our students to understand the practical world, the business of architecture. Then, last, we have intern programs that are contributed by our alumni group. They're individuals who play important roles in different firms. They will approach the student crowd and the right firms out there.

Are we doing a great job? I think it can be better. We can be much more disciplined in those three pipelines toward job creation and professional recruitment.

What do you see as the major trends within architecture right now and how do you familiarize yourself with them and bring them into the curriculum?

Architecture is a very old business. Actually it's probably as old as civilization because, as soon as we became humans, we needed to be covered, and then the design comes. So it still stays as a very simple process where you define space [according to your] life and you’ve built a space that accommodates that or transforms it. Then it can bring pride and honor to whoever lives in it or where ever it sits. And, still, that hasn't changed.

But recently if you asked what are the new trends, I would say the trends are that, one, there seems to be a very focused interest in what digital technology can do. I think the goal stays the same; it’s just the tools that are different. That will change the way we design and may even change the way we judge the look of a building. That's a trend. This program has invested a lot in digital technology, both from the building physics to the building forms. I hope in a couple years for our students, when they use computers, it would be same as when they would use a pencil. It will come very naturally and just be extremely fluid…Architecture is a very old business

Second is the environmental concern. This generation, the millennials, seems to really take on that not as just a polemical dimension but to really explore the ways to address environmental impact of building industry. We also very much enhanced that. That's a traditionally strong trade in this program. But we have enhanced it by bringing geospace into our landscape [program], but also bringing parametric design into something called verifiable feedback looping decision-making. In other words, in traditional buildings, you design, you build, and you find [what] is wrong but you can never change [it]. Now you can actually [predict] the performance of space in terms of energy profile. That is part of our investment as well in the program.

Lastly, culturally, there's a trend of creating landmarks. It’s the kind of celebrity building phenomena. This actually doesn't come from the design world, it comes from the business world. In other words, as land prices [increase] as the opportunity to build becomes increasingly scarce, anybody who gets hold of land wants to do a building that, on the one hand, will add value to their square feet and add value to their identity or IP strength. So therefore there is a need for iconic provocative buildings. Obviously that is not a majority or the major flow. But, in education, you can imagine how students are fascinated by those star architects as they try to make a name for [themselves]. This place is full of it because it’s in Los Angeles, in Hollywood. [And] we have educated two of the most iconic, Pritzker laureates—Frank Gehry and Thom Mayne. You can imagine how our students want to one day become Frank Gehry or Thom Mayne. So that's the trend.

Can you describe the relationship between the USC School of Architecture and the local Los Angeles community?

Well, it’s very tight. It's such a blend that makes this program strong. [The program] also contributes back to the community. I am not an expert on the history of the program, but it has been around for 100 years, this program… The graduates of the School of Architecture really played a role of making Southern California what it is.

But also it’s related to the creative community as well. Many of our graduates actually, if they do architecture, became part of the building industry or they move on to other creative endeavors, for example, Hollywood. I was told there are at least more than twenty architecture graduates who have come to the stage of the Academy Awards for set design or another field. So it's, by nature, really a part of the community.

How would you describe the relationship between the architecture school and the other departments in USC?

During my deanship, I've seen an increase in cross-disciplinary [collaboration]. The Annenberg Communications School—we have a journalism in art [program] that's contributed to by all the other schools in the art sphere, creative sphere. We have a joint program with the Viterbi School of Engineering. Then we also have classes with the Policy and Planning School. [We] also collaborate with the geography [program]... Now we have [a program in] gaming and the architecture of the city. There's a lot of interaction across disciplines but the difficulty is the architectural program is an accredited professional degree, so it has a lot of requirement from the architectural board nationwide.

Our impact on society is really through the physical presence of a building

I hope we get more electives, some more minor degrees that can be grouped around the core of architecture. But we are constantly in negotiation between the core courses and electives. That's where other interaction happens. The struggle continues. As I said, architectures is a very old business. It has its core abilities that take time to build up. That's why it’s also a 5-year program. This is a 5-year undergraduate program, the longest undergraduate program on campus.

How important would you say it is for a dean or for you to be a practicing architect?

There are good schools [where] the deans are not practicing architects… There's really no rule. It is a personal ability and the impact you bring to the school through what you do. I happen to be a practicing architect. So my agenda is, one, to influence the society and the community [make] buildings that actually bring culture and all that together. Our impact on society is really through the physical presence of a building. Because I believe that is eventually what it's going to transform a society and community. That's one.

Second, I also believe that all the representations of the world—no matter what you believe of the world—eventually there is the manifestation and representation of that belief or theory. So the process to reach the physical demonstration is so much more intellectual and [requires so much] research. Actually, by reaching a good physical result, that engenders deeper research and even more discussions... I think that, to me from my personal view, that is a very critical foundation for architectural education.

How have you seen the USC School of Architecture change over the course of your tenure?

First of all I think it is extremely difficult to change a place that has a 100-year tradition. It is almost impossible to change an institution or a place that has such a strong institutional memory. [But] that's good because there is a continuum of the knowledge, the belief and the practice. With that being said, I take a very alternative approach [by deciding] I would not change it, but I only nurture it in a way that becomes more of what has been instead of what it will be. So this is again my focus, my personal focus. When I first came in, I said ‘do nothing’. My first statement in our book is ‘do nothing’.

In other words, I wouldn’t do anything that changed the course of the school. What I would do would be only adding things. When you add new things the new things and the existing things have this very interesting dynamic in their growth pattern. Then, in this mix of new and old, if something, either old or new, is not really fitting for the time, they will recede or deteriorate. Or old things in the new environment… will grow more. So eventually good things will come out of the mix. It's like an agricultural work. All you can do is to slowly change the soil. You can't really pull the tree off. That's how you expect new fruits: work on the soil but not really change trees because the tree has a rootstock that’s been here for a reason.the highest level of ethics, I think, is to not do bad buildings

How do you teach students the code of ethics in architecture?

We have courses on the practical professional practice. This is where it's actually taught, the ethics of practice. That's one. Then, secondly, our professors who teach design, most of them, have their own practice in the world. So, through them, a student will start to get a sense of what's a good design and good designer. But the highest level of ethics, I think, is to not do bad buildings. It's like you can be as ethical as you want to be, but if you create bad buildings, that will have a bad influence forever. So how do we achieve that? I think the whole program is teach student to do buildings that are, how do I say? Buildings that can take you away for a moment, with pride. Forget about your routine troubles, just have that sense of departing. In other words, buildings that are so beautiful that when you look at them, it’s like wow, the world is worth living. Versus buildings that you look at and you say, ‘what happened?’ ‘What's wrong?’ So I guess that’s what we teach students, to really do great buildings that transform society, make the owners honorable and users pleasant. That’s the ultimate ethics of practice. Following the codes, that too. But if you follow all the code and you generate ugly buildings, that, to a dean—I don’t think that’s ethical.

Thank you.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

5 Comments

Excellent > "I think the whole program is teach student to do buildings that are, how do I say? Buildings that can take you away for a moment, with pride. Forget about your routine troubles, just have that sense of departing. In other words, buildings that are so beautiful that when you look at them, it’s like wow, the world is worth living. Versus buildings that you look at and you say, ‘what happened?’ ‘What's wrong?’ So I guess that’s what we teach students, to really do great buildings that transform society, make the owners honorable and users pleasant. That’s the ultimate ethics of practice. Following the codes, that too. But if you follow all the code and you generate ugly buildings, that, to a dean—I don’t think that’s ethical." — Qingyun Ma

excellent +1

Wise words.. Dean Ma added a lot of value to USC program since he took office.

Hands on, very effective training for student.

"f you follow all the code and you generate ugly buildings, that, to a dean—I don’t think that’s ethical."

That's an interesting position. I don't think I've ever heard a dean call for beauty so unequivocally. If the majority of people find traditional architecture more attractive than modernist, can one assume there would be no issue with students pursuing traditional design? Also, would this prioritization over-ride your call for social impact of building and also advancements of technology? Thanks.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.