As seen in the recent #NotMyAIA shake-up, the election of Donald Trump provoked a heated response within the architecture community. Many architects felt that now, more than ever, they had to voice their concerns over the president-elect's policies that threatened their professional values—chief among them, the leveraging of architecture to perpetuate xenophobic rhetoric, through one of Trump's loudest campaign promises, the U.S./Mexico border wall.

Many in architecture schools also felt the responsibility to organize and speak out, perhaps especially because of their position to influence the next generation of architects. Since the election, we've been reaching out to academic leaders from across the U.S. to hear how they were handling Trump's presidency—and what they were telling their students. We've gathered their responses here.

We sent the following questions to architecture deans/directors at schools across the country: What does Trump's presidency mean for architecture/architects? What responsibility do you have to your students to respond to the views of the President-elect?

In their responses, some also directly referred to #NotMyAIA; some sent responses that had also been sent to their student body. Leaders at the following schools have not yet responded to our request: University of Notre Dame, University of Texas – Austin, and Syracuse University. We'll add to this piece as more responses come in.

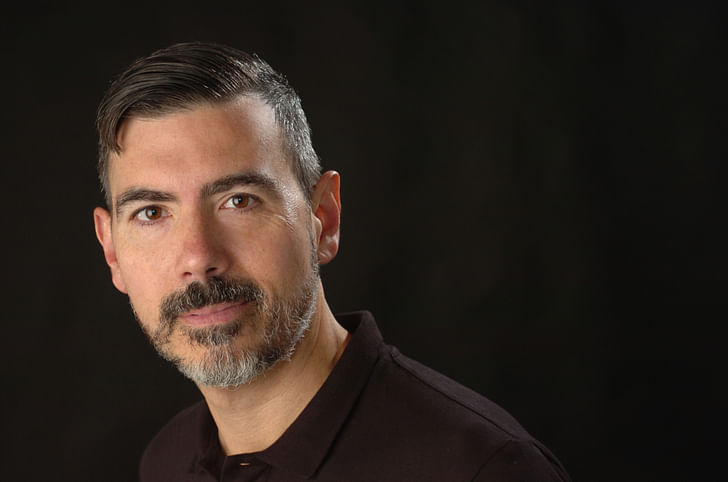

Hernan Diaz Alonso, Director of SCI-Arc

Full disclosure, I'm not an AIA member. I'm the director of SCI-Arc and I cannot assume that everybody thinks in the same way in our school, so my comments are coming from my own points of view.Architecture is not just a business. It is also a way of representing in built form what we think is important.

I am disturbed that the leadership of the AIA decided to speak on behalf of its entire 89,000 member constituency, and by implication architects in general, without consultation and public debate. Beyond the process by which it was released, I thought the statement itself was insensitive and tone-deaf to the tensions of this moment in American history. It seemed overly focused on commercial opportunities and blind to other demands for service to the public (which incidentally is an entire section of the AIA's own code of ethics). Architecture is not just a business. It is also a way of representing in built form what we think is important. It is a platform for questioning what we thought was important in the past. It is a way of working that enables necessary conversations in the present. If the AIA becomes nothing more than a lobbyist for the commercial interests of the largest corporate architectural practices, architects should question what their membership in the AIA actually means.

If we've learned anything during this election, it's that words matter more than ever. Speaking to each other matters more than ever. Thinking about the world we build for ourselves and future generations matters more than ever. The discipline of architecture is thousands of years old, but architecture [in the U.S.] has been professionalized for less than two hundred (the AIA was founded in 1857). Because of the AIA's relative youth compared to the entire history of architecture, we can only assume that what it is and what it does is still very much up for debate.

Amale Andraos, Dean of Columbia University GSAPP

At Columbia GSAPP, we feel that our responsibility is to continue to cherish the diversity of backgrounds, cultures and interests that our outstanding faculty and student body bring to the school. This creates a unique, exciting and challenging community where unwavering intellectual generosity and the desire to communicate and exchange across our differences are the foundations of how we learn and grow together.

Our engagement in shaping the disciplines of architecture and the built environment is predicated on a commitment to both continuity and change: bringing together disciplinary knowledge with the relentless interrogation of those disciplines’ foundations and boundaries, to produce new modes of scholarship, of practice and of action. Today, more than ever we need to empower our faculty and students to draw bridges, not walls.

This recasting is neither abstract, nor gratuitous but rather driven by the desire to broaden our responsibilities and abilities to engage with the realities of our interconnected planet — as we draw together across contexts, cultures and scales: the global and the local, the urban, the rural and the natural, architecture, cities and the environment, art and every day life.

Architects can draw lines that become walls that exclude and divide or they can draw lines as vectors that connect and render the invisible visible. We are the channels by which policy, law, economics, real estate, data science and public health (amongst others) become spatial and material, lived-in realities. Today, more than ever we need to empower our faculty and students to draw bridges, not walls.

[The following was also sent to the GSD Community]

The recent presidential election, if nothing else, has been a wakeup call not just for the nation but for the design profession at large. The debates have unraveled the extreme differences and disparities between communities and geographies — between the rich and the poor, the urban and the rural, the global and the local.

Sadly, the prevalent and proto-nationalist posture of much of the propaganda has found a convenient way to blame the “other” for everything that is wrong with our society. This clever sleight of hand does disservice to the disenfranchised, who have the right to homes, schools, work places, public spaces, and livable communities. These are just some of the necessary elements of a good and honorable life that require the talents of designers. We must make sure that our creative efforts towards the making of a just and better world are more effective and consequential than ever before.

The GSD’s diverse and international community is and remains vigilant against all forms of injustice. We must make sure that our creative efforts towards the making of a just and better world are more effective and consequential than ever before.

Our belief in the transformative power of knowledge and learning is one of our defining characteristics. This is the time for positive and united action. We will not only be shaped by these actions but will be judged by them too.

Long live kindness and the powers of the imagination.

Jonathan Massey, Dean of Architecture, California College of the Arts

Infrastructure Worth Building

The aim of rebuilding infrastructure might not seem particularly partisan. It was a priority for President Obama and should properly be a goal of the next administration, too. But infrastructure of what kind? When American Institute of Architects leadership promised to work with President-elect Trump on “schools, hospitals and other public infrastructure” and urged Congress to enhance “the design and construction sector’s role as a major catalyst for job creation throughout the American economy,” the statement put economic interest above ethics. It also aligned AIA with whitelash, since infrastructure for Trump begins with a border wall supposed to secure white prosperity through racial exclusion.

Upholding human rights and pursuing justice in Trump’s America requires us to build other infrastructures: schools and hospitals for sure, facilities for childcare and affordable housing, frameworks for solidarity and mutual care. Federal policies and purse strings give the President broad impact on our lives, so building infrastructures of inclusion requires national activism. It also calls for work at other scales. [Recently] legislators vowed that California would “defend its people and our progress,” stepping up to become a keeper of the future, while my city of San Francisco voted for school bonds, affordable housing, and police oversight. Withholding our labor is architectural agency in one of its strongest forms. A profession that serves justice is an infrastructure worth building.

Society — civil and, when necessary, uncivil — is another field for action. We can start by hearing “America” and “American” in their broader, hemispheric meanings... or discarding these frames to form affiliations that are cosmopolitan, subnational, and translocal. As with the Occupy movement a few years ago, such work can be at once practical and projective, small scale and big impact. Imagination is infrastructure. Another world is possible.

By housing, feeding, training, and treating our population, architecture transmits biopolitical imperatives that often transcend party politics. The new Jim Crow began with Clinton-era drug policies that spurred judicial construction and turned even some schools into prison pipelines. Understanding these modes of power can help architects better promote equity and autonomy via dwellings, farms, schools, and clinics.

Some work an architect must refuse. Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility has called on AIA to recognize human rights by barring members from making spaces for killing, torture, and abuse, and it has urged everyone to boycott prison design in the context of mass incarceration. Would you design Trump’s wall? How about a border station for his Homeland Security Department? A conversion therapy clinic? Withholding our labor is architectural agency in one of its strongest forms. A profession that serves justice is an infrastructure worth building.

Nader Tehrani, Dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, Cooper Union

I have spoken more extensively about these issues in the AN interview, so I am already on record with respect to the AIA statement. However, speaking more directly to your questions, I have the following reflections:

When I joined Cooper Union as the Dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, it came at a time when my practice, NADAAA, had established an important series of projects with some stability. As such, I saw the academic commitment as a way of giving back to the academy in substantive ways after over 25 years of teaching. This was a way of contributing my time, my thoughts and my finances to a project in which I am wholly dedicated. To do this, I think it important to define a space for learning, not just teaching. Within that space, the students' voices are important in establishing a discussion and helping them to drive a set of debates that will become their life projects.

The results of these elections have been catalytic to say the least. Just one week [before the election], we may have been speaking about the agency of formal, spatial and material strategies that drive architectural positions. With this incoming administration, and the words that define them, there is an urgency to establish a deeper understanding between what we do as designers and the ideological implications they harbor. While much of what is developed in design schools relies of the technical development of students — through drawings, fabrications, and engagement with software — how these media can come to dialogue with the state of discourse today becomes ever more important.Our responsibilities are to expose intellectual projects, to reveal positions and to enable the space of disagreement.

Thus, my responsibilities to the students, in great part, revolves around the possibility of creating a space of debate, where critical positions are revealed across the wide spectrum of ideological views. A couple of weeks ago, before the elections, we had the pleasure of hosting Patrik Schumacher, whose views on the entrepreneurial imperatives of formal research have been paired up with a political perspective of deregulation and freedom from policy that can be characterized as the extreme right of the political spectrum. What was interesting about that roundtable discussion was the way in which Schumacher tapped into the architect's desire to research, explore and experiment with a medium that has so much agency in forming our environment, on the one hand, and how he had paired up this necessity with political forces that have historically sidestepped, or marginalized questions of the environment, social equity, public space, and a range of other debates that can be attributed to a link to policy in poignant ways, on the other. The tension in his argument is palpable, and effectively a good index of our fraught historical moment... and of course, its contradictions did not go unnoticed by the students. Our responsibilities are to expose intellectual projects, to reveal positions and to enable the space of disagreement.

To this end, while there are many things in the professional realm for which the students may need to be prepare, our responsibilities to the students are to enable them to form critical opinions. The balance of an inter-disciplinary environment is to offer them varied lenses through which they may the same questions. In many ways, we are committed to preparing the students for the uncertainties that lie ahead, to think strategically, critically and speculatively, knowing fully well that they will be transforming practice as we know it, and not just necessarily fitting into a well defined path.

Responding to the views of the President-elect will require an immediate call to intellectual arms, but also the patience to oversee the process for years to come. If anything, Trump has given purpose to much of what we need to do in transforming the academic setting to educate a wider spectrum of the population and to create spaces of learning that enable tolerance, freedom of speech, and dissonance. If the roadblocks in the halls of Congress are a good index of what has come of public debate in the last decade, then this is also the time for us to imagine a very different way of building discourse moving forward. The oppositional binaries of good and evil that prepared such radical and transformational political decisions such as the road to war in Iraq will not suffice any more; in response we will need to build in some of the more difficult predicaments of political choices that produce the complexity of discursive gradients.

Sarah Whiting, William Ward Watkin Professor and Dean of the Rice School of Architecture

One of the extraordinary aspects of a university is that it is a condensed society: we live, study, and work in tight quarters. Universities concentrate together an especially diverse population — diverse in our backgrounds, diverse in our opinions, diverse in our ambitions.

Universities are also condensed versions of modern life, which is defined by social change – by a persistent “future always in the making,” as Louis Menand has put it. Every class asks you to think forward: to help articulate, design, construct the future that is always in the making.

To these multiple condensations, the RSA adds the factor of time: we spend more time together in one building than most other disciplines do on campus. We also spend much of that time together on too little sleep, which often limits our ability to take the time to think carefully, to talk thoroughly, and to work productively (how many times do we need to underscore the message that sleep is a necessary ingredient to intelligence?).We permit free expression because we need the resources of the whole group to get us the ideas we need. Thinking is a social activity.

Whatever your political beliefs, we can all agree that the election has further exacerbated these conditions. It can be hard to take the time to think through your individual reactions to the election process and the election results. I encourage all of you to take the time to formulate your own, reasoned opinions on these issues and more: on all of the current and historical issues that you believe most influence your “future in the making.” Being a student is exactly that: while I realize you can sometimes be overwhelmed by assignments and deadlines, if you step back for a moment, you’ll realize that these years are when you have the most time to formulate, test out, and advance your opinions.

Opinions are also always in the making – they cannot be fixed but must constantly advance, as your context changes. To that point, let me return to Louis Menand (and let me recommend his excellent book, The Metaphysical Club, which recounts the lives and thoughts of four powerful American thinkers who helped to define modern thought around the turn of the last century: William James, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Charles Sanders Peirce, and John Dewey): We do not (on Holmes’s reasoning) permit the free expression of ideas because some individual may have the right one. No individual alone can have the right one. We permit free expression because we need the resources of the whole group to get us the ideas we need. Thinking is a social activity. I tolerate your thought because it is part of my thought – even when my thought defines itself in opposition to yours (Menand, 431).

You’ve often heard me say that the foundation of the school is engaging in conversation. It’s why our extra small size lends us such an oversized advantage. The differences among individuals in the school are what hone those conversations. We advance those conversations – our projects – by engaging questions and issues that are critical to our collective future in the making. Please pause, consider your own opinions, remember that others are considering theirs, and take the time to talk together so as to further our future. These conversations might be spontaneous, spirited, longwinded, or concise. The school is not going to schedule one single conversation – that would be artificial. Each conversation you undertake is part of the ongoing conversation that is your education.

Mitzi R. Vernon, Dean, College of Design, University of Kentucky

At the heart of a talk given by architect, Manuel Aires Mateus in 2013 was the idea of the idea. As he spoke about the ephemeral nature of the built world and the recovery of ruins, he was asking, in the end, what do we leave behind?

Ideas are the only thing that may survive us. So, we must be careful what we build because the ruin is often our mark. The Great Wall of China, the Berlin Wall, the long history of medieval city walls…these are ideas of exclusion that are built into the landscape and survive. Are there city walls in the United States, a country wall? One could argue that we are formed by an idea that is precisely opposite. Ideas are the only thing that may survive us.

As for universities, it is our mission to offer unhindered passage (academic freedom) for students and teachers in the quest for ideas. We are fortunate at the University of Kentucky to have a president, Eli Capilouto, who is an unparalleled and formidable champion of inclusiveness. As the author, Stephen Greenblatt reminds us, “libraries, museums and schools are fragile institutions.” We might do well to re-read the history of Alexandria, Rome and the survival of an idea – Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things.

In our digital era the infrastructure of our ideas is captured by the binary system of 1s and 0s, indelibly it seems. We must be careful of this infrastructure as well. What we say is also what we leave behind.

While these comments have not been shared prior with my constituents in the College of Design, I hope that I have not unfairly represented my colleagues and those that I serve.

Update 12/8/2016: The following schools were also contacted for response: Yale University, The Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, Tulane University, Florida A&M University, Virginia Tech, California Polytechnic University Pomona, Howard University.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

10 Comments

Thanks for that!

why aren't the HBCU's included? Common Archtinet, get out of your comfort zone

Fair criticism.

Thanks @junegrant for the suggestion, any particular school you'd like to recommend?

7 HBCU

In response to Trump's campaign and the fever of his fanatical base, I have no doubt the dialogue within architecture schools will expand beyond formal, spatial, and material investigations, to also include investigations into the moral and ethical components of design. But what about the moral and ethical components of the practice of architecture? Will the culture and dialogue within firms change? Already, the practice of architecture is categorized by systematic misogyny and a dearth of minorities. In the shadow of a Trump presidency, I shudder to think how nasty female and minority architects will need to be in order for their voices to be heard. Perhaps this Archinect survey of architecture school leaders should be followed by a response by architecture firm leaders.

Did every Dean/Head in the US get this? Or only the select few that you showed, plus the few you admonished for not sending in their response (yet)? If not all schools, how did you select your list? It seems that if we are to confront the lack of inclusion, inequality, the "billionaire class" in some meaningful way, we should do so as a collective of all schools, on all sides of the discipline, not just the 1% brands that are represented so far in this piece, which will likely not be affected by anything Trump does...

Mostafavi said it best.

Timothy Snyder, Historian, author of Bloodlands, Yale professor with 20 lessons to take to heart now. I was only going to post #3 regarding professional ethics, but then I realized that 1,2,7, 8, 9,19 20 were also relevant here, especially given how the AIA Leadership responded.

Timothy Snyder

November 15 at 9:57pm ·

Americans are no wiser than the Europeans who saw democracy yield to fascism, Nazism, or communism. Our one advantage is that we might learn from their experience. Now is a good time to do so. Here are twenty lessons from the twentieth century, adapted to the circumstances of today.

1. Do not obey in advance. Much of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then start to do it without being asked. You've already done this, haven't you? Stop. Anticipatory obedience teaches authorities what is possible and accelerates unfreedom.

2. Defend an institution. Follow the courts or the media, or a court or a newspaper. Do not speak of "our institutions" unless you are making them yours by acting on their behalf. Institutions don't protect themselves. They go down like dominoes unless each is defended from the beginning.

3. Recall professional ethics. When the leaders of state set a negative example, professional commitments to just practice become much more important. It is hard to break a rule-of-law state without lawyers, and it is hard to have show trials without judges.

4. When listening to politicians, distinguish certain words. Look out for the expansive use of "terrorism" and "extremism." Be alive to the fatal notions of "exception" and "emergency." Be angry about the treacherous use of patriotic vocabulary.

5. Be calm when the unthinkable arrives. When the terrorist attack comes, remember that all authoritarians at all times either await or plan such events in order to consolidate power. Think of the Reichstag fire. The sudden disaster that requires the end of the balance of power, the end of opposition parties, and so on, is the oldest trick in the Hitlerian book. Don't fall for it.

6. Be kind to our language. Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking, even if only to convey that thing you think everyone is saying. (Don't use the internet before bed. Charge your gadgets away from your bedroom, and read.) What to read? Perhaps "The Power of the Powerless" by Václav Havel, 1984 by George Orwell, The Captive Mind by Czesław Milosz, The Rebel by Albert Camus, The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt, or Nothing is True and Everything is Possible by Peter Pomerantsev.

7. Stand out. Someone has to. It is easy, in words and deeds, to follow along. It can feel strange to do or say something different. But without that unease, there is no freedom. And the moment you set an example, the spell of the status quo is broken, and others will follow.

8. Believe in truth. To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights.

9. Investigate. Figure things out for yourself. Spend more time with long articles. Subsidize investigative journalism by subscribing to print media. Realize that some of what is on your screen is there to harm you. Learn about sites that investigate foreign propaganda pushes.

10. Practice corporeal politics. Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.

11. Make eye contact and small talk. This is not just polite. It is a way to stay in touch with your surroundings, break down unnecessary social barriers, and come to understand whom you should and should not trust. If we enter a culture of denunciation, you will want to know the psychological landscape of your daily life.

12. Take responsibility for the face of the world. Notice the swastikas and the other signs of hate. Do not look away and do not get used to them. Remove them yourself and set an example for others to do so.

13. Hinder the one-party state. The parties that took over states were once something else. They exploited a historical moment to make political life impossible for their rivals. Vote in local and state elections while you can.

14. Give regularly to good causes, if you can. Pick a charity and set up autopay. Then you will know that you have made a free choice that is supporting civil society helping others doing something good.

15. Establish a private life. Nastier rulers will use what they know about you to push you around. Scrub your computer of malware. Remember that email is skywriting. Consider using alternative forms of the internet, or simply using it less. Have personal exchanges in person. For the same reason, resolve any legal trouble. Authoritarianism works as a blackmail state, looking for the hook on which to hang you. Try not to have too many hooks.

16. Learn from others in other countries. Keep up your friendships abroad, or make new friends abroad. The present difficulties here are an element of a general trend. And no country is going to find a solution by itself. Make sure you and your family have passports.

17. Watch out for the paramilitaries. When the men with guns who have always claimed to be against the system start wearing uniforms and marching around with torches and pictures of a Leader, the end is nigh. When the pro-Leader paramilitary and the official police and military intermingle, the game is over.

18. Be reflective if you must be armed. If you carry a weapon in public service, God bless you and keep you. But know that evils of the past involved policemen and soldiers finding themselves, one day, doing irregular things. Be ready to say no. (If you do not know what this means, contact the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and ask about training in professional ethics.)

19. Be as courageous as you can. If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die in unfreedom.

20. Be a patriot. The incoming president is not. Set a good example of what America means for the generations to come. They will need it.

--Timothy Snyder, Housum Professor of History, Yale University,

15 November 2016.

---

"We permit free expression"

Ok if they permit now on I can sleep relaxed...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.